The General Slocum

The General Slocum has been part of my life for as far back as I can remember.

My great grandmother, Amelia, 20 in 1904, lived in Little Germany. She knew, or knew of, many of the principal players in the events of June 15, 1904 and as a child obsessed with both history and ships I would often ask her to tell the story of the disaster and its aftermath. “I would have been aboard the Slocum that day, but at the last minute….” became the central motif of literally thousands of family legends in the NYC area, but, to her credit, my great grandmother never made that claim. As my mother recently put it: “There wasn’t a chance she would have been there. Her father would never have wasted money on something like excursion tickets.” So, extreme paternal frugality saved her and her two sisters from probable death that morning. I was, possibly, five years old when I became interested in ‘grandma’s shipwreck,’ but of course I did not write any of the stories down, nor did I tape record them. Sadly, no one else did, either. For a time, my interest in ships waned, and ‘though I saw great grandmother frequently, until I was well into my teens I did not hear of the General Slocum again, except in passing.

My great grandmother died in 1982, but fortunately, on the last Thanksgiving that she was well enough to attend the family get together, she and her friend, Fay, also from Little Germany. spoke at length, about the tragedy and its aftermath. At 15 I was old enough to remember the details clearly – though, once again, I neither tape recorded nor wrote them down. They spoke of “Mary” who organized everything and who died in the fire, of Reverend Haas losing his wife, of how a number of the survivors came back home aboard an elevated train, but so few got off that people assumed it was only the first of many trains (it wasn’t) and finally, of how shocking it was to see adults, trained from birth to keep all emotion hidden in public, reacting with hysteria as the known death toll mounted and relatives failed to return home. Both remembered a woman falling to her knees in the street, screaming and tearing at her hair when she learned of the death of her family. So many questions I wish I had thought to ask while I still had the opportunity. “Mary” was, I much later learned, Mary Abendschein, a middle aged single woman who channeled her energies into improving St. Marks German Lutheran Church and who, in fact, had organized the fatal voyage. But, did my great grandmother and Fay recall the name of the hysterical mother? Did she ever find her children, or had they been lost? How many of their friends survived, how many didn’t, and who were they? I’m glad that I got a final chance to hear of the Slocum as a young adult, but regret not having had the time to learn more straight from the mouths of those who were there.

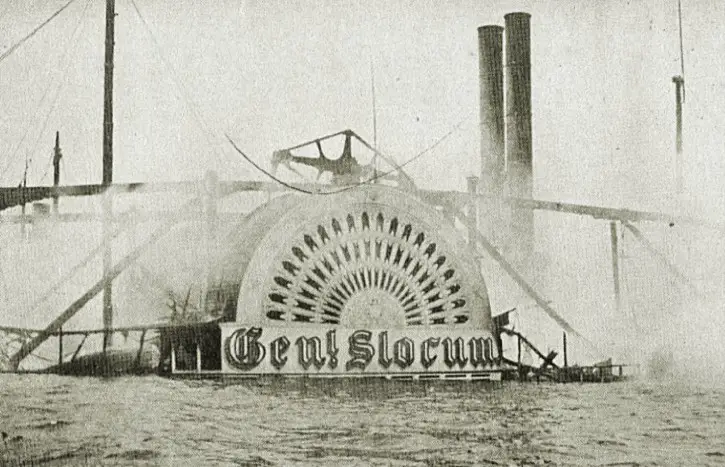

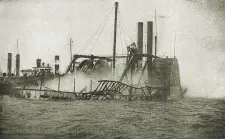

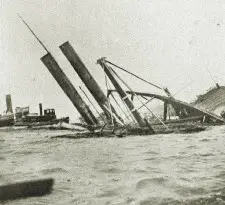

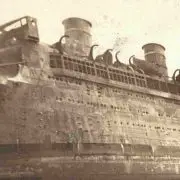

A basic outline of the Slocum story for those not familiar: The General Slocum, a wooden sidewheel vessel owned by the Knickerbocker Steamboat Company, caught fire while on a chartered excursion of the St. Mark’s German Lutheran Church Sunday School. Rather than immediately put his vessel in to shore on either side of the East River, the captain kept in midstream, and at full speed, for at least five minutes beyond the point where the fire first became uncontrollable. The majority of the passengers could not swim, and those not forced overboard by the flames in mid-river, had to jump, or were thrown, into the water when the ship grounded, bow-on, on North Brother Island and the upper decks began to collapse. Medical staff and patients from the hospital on North Brother Island, and a flotilla of small boats and tugs, worked fast to save the drowning, but within a quarter of an hour of the grounding there was no one left to save. Later in the afternoon, the charred hulk of the Slocum drifted free of the beach and sank on the Bronx side of the river, in the direction of Throgs Neck.

There follows a history of the General Slocum, from J.S. Ogilvie’s History of the General Slocum Disaster:

The General Slocum was one of the best known vessels about New York Harbor. Since the time of her launching, in 1891, she has been employed in so many different capacities, and on so many different runs, that possibly five out of every ten people in New York City have, at some point, been aboard her, or have seen her at close range.

Built for the Rockaway service as a sister ship to the Grand Republic, she was kept on that run during most days of the summer months, and during the thirteen years she has been in service she has carried to that resort almost enough people to equal the population of this city.

As an excursion boat she was easily one of the most popular of all the vessels that ply the surrounding waters. Her build did not allow much room for dancing, but the younger folks usually found room in a rather small space on the main deck for this amusement, while the general arrangement of the vessel, with corners and spaces to suit every kind and class, gave her great popularity. During the excursion season, which comes before and after the Rockaway season, she was employed almost every day by excursion parties.

The General Slocum, too, has followed every international yacht race held off Sandy Hook since the day she was built. When she was in her prime and was the finest of the harbor craft, great sums were paid for her on the yacht courses. Since 1891, however, other vessels have appeared which are faster and more suitable to open sea sailing than the Slocum, and she has gradually become the poor man’s transport at the races.

At her launching, everybody was full of praise for Divine Burtis, Jr., the boat builder, of Conover Street and Atlantic Basin, Brooklyn, who built her. The contract for her construction as given out on February 15, 1891, and on April 18th of the same year, three days more than three months later, she was launched.

As she was the finest vessel in the harbor, and having been built in Brooklyn, that city took pride in her and turned out in a crowd at her launching. Miss May Lewis, the niece of the then-President of the Knickerbocker Steamboat Company, her owners, broke the bottle of wine over her bows as she left the ways.

When the vessel a short time later made her trial trip, she was described as the realization of the boatbuilder’s dream. She was provided with three watertight compartments, which was something entirely new then in such craft, and she was said to be unsinkable. Her dimensions were: length of keel, 235 feet; breadth of hull, 37 feet 6 inches; depth of hull, 12 feet 3 inches; length of deck, 250 feet; breadth of deck 70 feet.

Her body was of white oak and yellow pine, and she was of about 1200 tons. Her engines, which were three of the most advanced pattern, were built by the W.& A. Fletcher Company, of Hoboken. She was a sidewheel boat, each wheel 31 feet in diameter, bearing 26 paddles. She had a steam steering gear of the latest pattern, and was lighted by 250 electric lights. She had a speed of about 18 miles an hour.

The General Slocum had three decks, the main deck provided aft with a comfortable and roomy cabin for women, and with a restaurant forward. The next above, the promenade deck, held the main cabin, richly lined with highly polished sycamore and upholstered in red velvet. Forward and aft of this cabin were roomy deck spaces. The band usually played on the after-part of this deck. The hurricane deck was provided with a running bench all along the outside. Her two funnels were almost amidships and were placed one on each side. Her body was painted white, and her funnels a medium yellow, while her name in large gold letters stood out on either side. She carried a crew of 22 men, a captain and two pilots.

Much would later be said about the General Slocum being a “hoodoo ship.” For a time, in the 1970s and early ‘80s, that particular canard became an integral part of the tale, but a review of the ship’s pre-fire record shows that her life was certainly no more ill starred than that of any other river boat. This segment, also from Ogilvie, details the major mishaps of the boat’s fourteen year career:

HER MISFORTUNES

The first serious mishap to the General Slocum happened on July 29, 1894, when, on a run home from Rockaway, on which 4700 persons were aboard, late at night she ran on to a sandbar and struck with such force that she carried away several stanchions and injured her electrical apparatus so that every light on board was extinguished. A panic followed, in which women who fainted were trampled upon, and men fought with each other to get to the boats. Pandemonium reigned for half an hour, until order was restored by the crew. Then it was found that hundreds had been injured in the wild scrimmage.

In August of the same year she met her next mishap. During a heavy squall she ran on a bar off the end of Coney Island. It was night, and again a panic raged. The captain and crew fought down the scrambling passengers, and finally when the storm abated, transferred them to another vessel.

In the following September she was again laid up through a collision in the East River with the tug R.T. Sayre. She sustained damages which cost $1000 to repair, and drifted helplessly about the river for some time, at last to be saved from going on the rocks off Governor’s Island. Minor accidents happened to her until July, 1898, when she again was put out of commission by the steam lighter Amelia, with which she collided off the Battery. The two vessels locked and were being carried on the Battery Rocks when tugs separated them.

In June, two years ago, while returning from Rockaway with 400 people aboard, in order to avoid a small sloop she again ran on a bar, where she remained all night, her passengers camping out on deck and in the cabin.

The most serious affair that happened aboard the Slocum before the recent disaster, however, occurred on August 17, 1901. She then had aboard 900 persons, mostly men who were described at the time as Patterson Anarchists. When they boarded the vessel at Jersey City most of them were intoxicated. The Slocum’s owners had contracted to take the party to Rockaway, and when the vessel passed outside the Narrows she encountered a heavy sea.

Some of the passengers ordered the captain to turn back. He refused, and then a mob organized to compel him to obey their wishes. The mob first started a panic among the women aboard, and then began a march on the pilot house to lay hands on the captain. The deck hands and spare men from the engine force were quickly called upon, and, with the captain, they attacked the mob and a pitched battle was started. Little by little the mob, and all other passengers were driven into the cabins, the doors of which were locked. An hour later, the Slocum stopped at the police pier at the Battery, where seventeen of the men were turned over to the police. Most of them were later sent to jail.

The officers of the Knickerbocker Steamboat Company have frequently been up before the authorities for overcrowding the Slocum. Almost every year special men were detailed to watch her, and charges against her were often made. In 1895, the company was fined $1,670 for a violation.

One event this author missed came early in the Slocum’s career, when a young girl was crowed overboard off of an upper deck and drowned. Evidence that the Slocum was considered a ‘cursed’ vessel from before the fire is non-existent, and the affairs as outlined by Ogilvie, although unpleasant, are not anything that could not, and did not, happen frequently aboard other turn of the twentieth century harbor craft.

So, when the congregants of St. Marks German Lutheran Church, on East Sixth Street, boarded the General Slocum on the morning of Wednesday, June 15th, 1904, en route to a Sunday School picnic at Locust Point on Long Island Sound, there was probably little or no sense of foreboding. It was a beautiful late spring day, the voyage to Locust Point was just long enough to be interesting, and in an era where free time was measured in minutes rather than hours or days, 12 hours spent doing nothing but relaxing in a pleasant place with old friends was a rarity to be anticipated for weeks in advance and remembered fondly for weeks afterwards. Within four hours, 958 of the passengers would be dead or fatally injured, the Slocum would lie sunken with only a portion of her paddle box and her funnels breaking the surface, and fewer than 400 survivors would be slowly making their way back to the Lower East Side, or were recovering in several hospitals.

Because there were so few survivors, interviews – some lengthy, some partial – given by almost half of those saved exist.

We begin with one of the most descriptive accounts if the fire, as well as one of the saddest. It was left, by Mrs. Catherine Kassebaum, 52, of 196 Guernsey Street, Brooklyn.

Catherine Kassebaum was eventually reunited with her daughter Annette, “Nettie”, 30. Nettie had remained aboard the Slocum until a tug appeared through the smoke. She jumped down to it, breaking her leg, but was saved. Lost from the Kassebaum party were Henry Schnude, 32, a Deacon of St. Marks Church, his wife, Anna, also 32, their daughters Mildred, 2, and Grace, 4, Mr. William Schnude, 61 and his wife, Louise, 58, Mrs. Frieda Toniport, 27, and her children Frances, 4, and Charlotte, 1 ½.

Frank Prawdzicki, 12, of 85 East Third Street, was one of the first passengers to spot the fire. He ran to the pilot house and attempted to warn Captain Van Schaick, only to be told “Get the hell out of here!” Frank survived, as did his mother, Mary, 36, but his sisters Annie, 15, Henrietta, 13, and Gertrude, 3, died, and his infant sister Johanna, 1, was lost and never recovered. Mary Prawdzicki gave birth to a second son, Alfred, in 1906.

This account, by Anna Weber, tells the story of an extended family more fortunate than the ill fated Kassebaum party. It also contains a link to the final Slocum survivor, Adella Wotherspoon.

There was never a happier party than we were when we boarded the boat Wednesday morning. The children danced around when I was preparing the lunch the night before and we started early. My husband and myself, my children Emma and Frank, and my sister Martha Liebenow met my brother, Paul Liebenow and his wife, with their six month old baby in her arms, and Helen, six years old, and their baby girl three years old at the dock. We had invited them to go with us to the excursion, and we went on board laughing and talking, the children ahead with my sister.

We went to the middle deck, near the forward part of the boat. The sun was shining, and the boat glided through the water so smoothly that the children could play around without any danger, and were told to remain within call. The four little ones romped back towards the stern of the boat with my sister.

We were sitting in a circle talking when a puff of smoke came up the stairway leading to the deck below. It was a big puff of smoke and startled everyone.

‘Don’t mind that, it’s the chowder cooking’ some one said, and then we laughed at our fears, but the laughter changed to a cry of horror when a sheet of flame followed the smoke.

I cried for my children, and my sister in law with her baby ran back to search for her two little ones. The flames kept sweeping up, growing higher and spreading. My husband and my brother had gone to look for the children.

Then we were all separated. I rushed here and there, looking for my children and saying to myself that my husband had found them. The flames were sweeping back as the boat raced on, and it was like the breath of a furnace.

‘Get life preservers’ said a man, and we all stood up on camp stools and on the benches and reached for life preservers. Some of them we could not budge, and the others pulled to pieces and spilled the crumbs of cork over our heads. The heat was blistering and the flames swept along the roof of the deck and scorched our fingers as we tried to snatch down the life preservers. The flames drove those who were standing around me back and over to the side of the boat.

Nobody could live in heat like that. My face was scorching and my hair caught fire. I went to the side of the boat and swung myself over the side by a rope. Every time my hands, face or body would come in contact with the sides of the vessel it would blister my flesh.

I don’t know whether I dropped or whether I was pushed off. I found myself struggling against the water. There were others struggling in the water around me, and they were pulling each other down. I cried for help and heard a man, who was in the water, tell me to come nearer, that it was too hot where I was for him to swim to me. I was pulled on shore on North Brother Island and then went back to the water to look for my children.

Before I let go of the rope, the vessel was one mass of flames. I knew that the children couldn’t live there and thought I might keep them from drowning. I found my husband with his clothes burned off, looking for the children, and then they took us both to the hospital.

At the hospital I found my brother and his wife. Some one restored to them their six month old baby, which had been pulled from the water. My two little children and her two girls are missing.’

Anna Weber, 31, and her husband, Frank, 35, lost both of their children ,Emma, 10, and Frank C. Jr., 7, in the fire, along with her sister, Martha Liebenow ,29, who resided with them at #404 East Fifth Street. Paul Liebenow, 33, and his wife, Anna, 32, lost two children, Anna, 3, and Helen, 6, whose body was never recovered. Their infant daughter, Adella, 6m, became the final known General Slocum survivor, dying in 2004.

The Department of Charities General Slocum Report has a table in which the missing are matched with the body most likely to have been theirs. Helen Liebenow, 6, is thought to be body #5, a 6 year old girl buried in grave 5 of row 1 at the Lutheran Cemetery.

Margaret Maurer, 48, was the wife of George J. Maurer (53) the leader of the band that played aboard the General Slocum’s final voyage. She died, of pneumonia following burns, on June 23, 1904, joining daughters Clara, 12, and Matilda, 14, and husband, George, who was found with the print of a shoe heel stamped into his forehead. ‘Professor’ Maurer’s song list for that morning consisted of:

1) Unser Kaiser Friedrich

2) Poet and Peasant

3) Bird of Passage

4) Waldvoeglein

5) Vienna Swallows

6) Swanee River

7) On The Beautiful Rhine

8) Dutch Patrol

9) Hip Hip Hurrah

10) Carousal

For the return voyage, the program was:

1) Unser Kaiser Friedrich

2) College

3) Ever or Never

4) Under The Double Eagle

5) America

6) The Picadore

7) Werner’s Parting Song

8) Children’s Carnival

9) Princess Pocahontas

10) Mrs. Sippi

11) Home Sweet Home

Many of the survivors spoke of the “younger set” dancing to Maurer’s band that morning, and many witnesses on shore testified that although it was evident to them that the ship was ablaze, apparently it was not as immediately evident aboard the ship, for the band kept playing. The wave of passengers who ran from up forward, described by so many survivors, overwhelmed the small band. Maurer was seen being carried into the water holding one of his daughters and, from the heel mark on his head it is likely he was rendered unconscious by one of the other passengers who rained down when the railing was broken away.

Cornet player August Schneider, 34, of 322 Stanhope Street, Brooklyn, was luckier than George Maurer. His family traveled with him on the excursion, and they were not entirely annihilated.

We were playing on the upper deck. The band, of which George Maurer was the leader, was composed of seven musicians. We were seated in the stern when a whole crowd of people suddenly rushed toward us, shouting and screaming. At least half of them jumped right overboard. It wasn’t until a few seconds afterward that we saw smoke and fire. The wind, luckily, was blowing the flames away from us.

I got my family together and told them to stick close to me. I took my little Augusta, 3 years old, on my arm and was just considering the best place for safety when the deck broke, and fell with the ruins.

I still held my child, but my wife and the other two children were torn away from me and I didn’t see them again and do not know where they are. I was taken off by rescuers in a tugboat.

Dora Schneider, 32, was lost, as were her daughters Catherine, 8, and Amalia, 6.

Reverend George C.F. Haas, 50,of St. Marks German Lutheran Church was accompanied by his wife, daughter, sister, sister- in – law and nephew on the Sunday School excursion. He recalled:

It has been my practice every year to make a tour of the boat as soon as we started on our annual excursion, to see that everything was all right. Shortly after the steamer left the Third Street pier that morning I started from the promenade deck to make such a trip. I had just completed the round of the steamer on the several decks forward and aft, and was on my way back to the promenade deck when I saw smoke coming up a narrow gangway leading from the lower main deck.

I thought at first that the smoke might be blowing that way from the galley, where I know they were preparing to cook the clam chowder, but the smoke speedily increased in volume and I soon realized that it was something more serious. I ran to where my wife was sitting on the promenade deck and returned with her to the main deck, at the same time giving the warning to everybody I met to go to the stern of the boat.

On reaching the main deck I drove the people before me toward the stern, but that was not difficult, for many of them had noticed the smoke almost as soon as I had, and were hastening away from the point of danger. When I reached the end of the cabin, I tried to close the sliding doors so as to prevent the smoke and flames from being blown through them to the open part of the deck, where a big crowd had gathered. I closed one of the doors, but the other I could not move.

I cannot tell how many minutes elapsed between the time when I first saw the smoke and when the steamer was all in flames. It seemed only a few seconds to me, but from what I can remember having done in that interval it must have been considerably longer. My wife and I stood together by the rail until we saw that the upper deck was about to fall upon us. We saw nothing of our little girl, who had been playing with other children. My sister stood near us. None of us could swim, but when we realized that it meant certain death to remain longer on the steamer we all jumped overboard together.

We had on life preservers, but I don’t think we had them properly adjusted. At all events, after I got into the water I did not float, and I immediately became separated from my wife and sister. I have no recollection as to how I was rescued. The first thing I knew I found myself on North Brother Island, and was brought from there to the hospital. I did not know that my sister had been saved until I found she was a patient in the same hospital, and I have received no tidings of my wife.

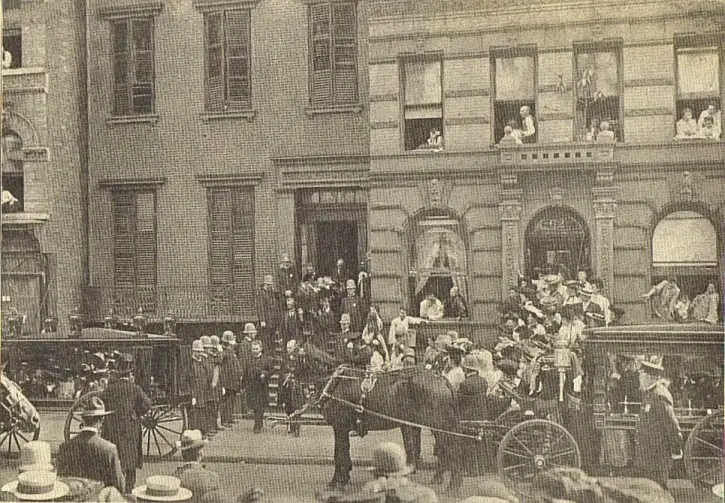

Of the Haas party, only the Reverend and his sister, Emma, 30, escaped. Anna S. Haas, 46, died, as did her daughter, Gertrude, 13, her sister, Mrs. Sophia Tetamore, 31, of 1471 Bushwick Avenue, Brooklyn, and Mrs. Tetamore’s son Herbert, 3. Reverend Haas made his first post-fire public appearance, his head swathed in bandages, at his wife’s funeral in the front parlor of their home at 64 East Seventh Street. Those in attendance were surprised at how ill he seemed. Anna Haas’ was the only body recovered at that point, but just as her service began news arrived that the remains of Mrs. Tetamore, whose face had been destroyed, had been identified by certain markings on her body. Sophia’s coffin was taken to the Haas home and, after services, both sisters began their final journey together. Gertrude Haas’ was one of the final bodies identified (her death certificate was #3617, Mrs. Tetamore’s was 3160, and Mrs. Haas’ 2930) while Herbert Tetamore was never found.

St. Marks Sexton, Joseph Halphusen, and his family, were more fortunate than the Haas party:

We had been gone about an hour, I suppose, and I have no idea how far we had gone, when I suddenly saw a rush toward the center of the boat, followed by a cry of alarm.

Panic ensued. Sheets of flame followed the roiling clouds of smoke, and the fearful rush began to the sides of the boat. Women and children were thrown down and trampled on. Many were pushed overboard, and more jumped into the river.

It seemed to me that the crew of the boat lost their heads- they were undisciplined, and did not do what sane men would have done to stay the panic and restore order.

There was little time to secure life preservers, and I doubt if many thought of them.

I assisted as much as I could, but I also had my daughters, Mina, 12, and Clare, 10, to look after. I took them to the top deck, and led them on to the paddlebox. The flames were all about us now, and I was merely waiting for the moment to order my children to jump.

Tugs were coming to the rescue from all directions. In the water I could see on every side the despairing struggles of the dying. Finally, the flames crept so close to us that they almost set our clothes afire. I signaled to a tug and called to my daughters to jump.

The tug Sumner picked us up.

Because of the proximity to shore and the immediate presence of many rescuers on hand, a few passengers who ‘drowned’ that morning were brought back. There is a uniform quality to their accounts – a struggle, a ringing in their ears, a sudden ‘acceptance’ of what was happening, and then blackness. One who was brought back was Susan Schulz, 24, of 414 East Ninth Street:

It was too awful to remember about, and I wish I could forget it all. Such tearing pushing and hauling I never saw before. In the water it was worse. Women fought for small pieces of board, grabbed each other for support, some of them begging others to save their children. I don’t know how I got in the water, but after I had been in a short time I felt a sort of suffocation. I could not breathe. My ears tingled and I seemed to hear sounds like music afar off. I don’t remember any thing more until I found myself on the island with the doctor working over me.

Walter Mueller, 10, was the son of Bernard, 38, and Valesca Mueller, 29, of 95 2nd Avenue. They were lost, as was their son, Edgar, 4, but children Walter, Louis, 9, Arthur, 6, and Grover, 13, survived.

Bernard Mueller died in the hospital on June 23, 1904. Before he died, he stated:

The orphaned Mueller children were taken in by their grandmother, Johanna Hagar. Grover died in South El Monte, California, in April, 1968.

There is often the mistaken tendency to consider ethnic neighborhoods, both historical and contemporary, as being homogenous. Little Germany was really a small town within a large city, and the passenger list of the General Slocum reflected all levels of German-American society as it existed in 1904. Nicholas Balser, 56, of 422 East Eighth Street escorted his wife Amelia, 46, and family friend Maria Fickbohm, 40, of 91 Avenue D, and her three children, Maria, 14, Ernest, 12, and Frederick, 9, on the excursion. Mr. Balser was a pharmacist, whose business acumen allowed him the luxury of a free Wednesday (an advertisement for his pharmacy, and “Wild Cherry Cough Balsam, .25 the bottle” appeared in the program handed out to Slocum excursionists that morning) while Peter Fickbohm’s saloon allowed Maria the luxury of a telephone (Orchard 505) and servant, Kate Cibilski, 18, who traveled with the family on the outing. Mr. Balser, still in the wet clothing in which he was rescued from the river, returned to the Fickbohm’s saloon where he gave this account:

Shortly after leaving the pier, I left my wife and the Fickbohms on the middle deck. They were sitting in the bow. I took little Freddy Fickbohm on the top deck to show him the points of interest. We were approaching the island when, looking forward, I saw flames shooting up from the deck below. Unclasping my knife, I slashed at the fastenings of the life rafts nearby. But, they were secured by wire instead of rope. I told Freddy to stay with me, but when I returned he has disappeared. I then started for my party but was driven back by the flames.

The whole front part of the boat by this time was a mass of fire. For the time being, so near were we to shore that there was no panic. The passengers, mostly women and children, retreated before the flames. All thought that the boat would put into shore at once, but it seemed fully five minutes or more before she swung inshore. By this time, the scene was terrifying. Women threw their children overboard and then followed. They had no other refuge from the flames, which swept everything before them.

I rushed aft, calling to my wife, but I could not see her, and in the roar of the fire and the cries of the panic-stricken passengers, she could not hear me. I was driven back to the wheelhouse by the fire. I thought I was trapped. There was no chance for me to go farther aft, and below was the fire.

I threw myself over the railing and dropped into the water on the side farthest from land. It was then I received these burns. The waster came only to my armpits, and I could have walked to the shore. When I finally emerged, I looked back and to my dying day I’ll never forget the scene. Around me were scores of bodies, most of them charred and burned. I helped as many as possible of those living to the land. From the stern of the boat, where hundreds of persons were huddled fighting like mad to leap into the water, I saw dozens of women throw themselves over the side.

I searched in vain for my wife. Body after body was laid out on the shore, but hers was not among them. Then someone said that a party of women and children had been sent to the city, and a neighbor told me my wife was among them.

Catherine Balser, in fact, died that day, as did Maria Fickbohm, her servant Kate Cibilski, and two of her three children. Only Freddy Fickbohm, whose position at the onset of the fire- far forward and on the top deck- gave him an excellent chance at survival, escaped alive. A Fred W. Fickbohm, of the right age and born in New York, is shown in both the 1920 and 1930 census as living in Newark, New Jersey, with his wife and daughter, both named Lillian.

If Nicholas and Catherine Balser, whose prospering pharmacy gave them the luxury of a midweek day off together, and Maria Fickbohm, with her successful family business, telephone, and servant represented one extreme of life in Little Germany, then 47 year old Mrs. Emilia Richter, of 404 East Sixth Street represented the other. However, in the eyes of the community, both women were equally respected. Mrs. Franz Wilhelm Richter had been left widowed with seven children, and an elderly mother to support. Determined not to fall upon charity, and equally determined to keep her children in school for as long as possible, Emilia worked several jobs. According to one account, for a time she worked up to 20 hours each day as an office cleaner, a washwoman and a piece worker at home. Had “help” been offered from outside of her immediate family she most likely would not have accepted it – and after the disaster neighbors spoke of her approvingly, if not glowingly. By 1904, her three eldest children had entered the work force and for the first time in a long while things were looking up for the Richter family. The General Slocum excursion was probably the first “vacation” they ever had. Emilia’s 15 year old son, William, was working in an office and could not make the excursion. Only he and his sister Frances, 10, remained alive by the afternoon of June 15th. Mrs.Richter, along with her children Emilia, 20, Lizzie,19, August, 14, Ernest,12, and Annie, 8, drowned in the water off North Brother Island. Frances Richter gave this account of her mother’s sad final moments:

“The first thing I knew was a lot of people yelling ‘fire!’ and in almost a minute the whole middle of the boat seemed burning. The wind blew the flames towards us, and I saw the dresses of several children catch fire all at once. The screaming was awful. My mother called out to me ‘Don’t be afraid! Hang over the side!’ then she pushed me over the rail and I fell down to the lower deck, outside, and I hung to the railing with my feet and legs in the water.”

A final account of the family survives, leaving one to wonder what became of the three survivors of Emilia Richter:

Frances, the ten year old girl who was saved, walked hand-in-hand with her brother, who had not gone. The boy is only fifteen, but he acts like a grown man. The day after the funeral he went back to his work in a commission house downtown, but his employer said to him in kindly fashion: ‘Take the week off; come back next Monday.’

‘I was glad,’ said the boy simply as he came home and took off his coat, ‘for now I can get the moving done.’ With a little help, he moved over what furniture would be needed from their own tenement to that of his grandmother. The children will live with her for the present.

‘She oughtn’t be left alone,’ explained the boy. ‘I will have to take care of her and my little sister. Well, I don’t know just how I’m going to do it, but I’ll manage it somehow. There isn’t anyone else to do it.’

A William Richter, born in 1888 and a bank clerk, is shown as residing with his uncle and aunt, Harry and Alice Richter, on West 25th Sreet in Mnahattan, in the 1910 census. Franis Richter, 15 or 16 when the census was taken, was not residing with her brother, if this is, in fact, the William Richter.

Life in Little Germany was austere in a way that seems unbelievable in the 21st century. My great grandmother was raised in a home where German only was spoken, a switch with which to discipline the children was kept beside the family Bible, the evening meal was preceded by an interminable prayer delivered by Vater, and relentless emphasis was placed on education and personal achievement. It was a typical home for that time and that community. Floors were to be scrubbed by hand and not mopped (mops only spread the dirt) emotions were simply not shown in public and very seldom in private (a very fond memory of mine is of my mother affectionately commenting to my great-grandmother ‘You Germans have no sense of humor’ and my great-grandmother deadpanning ‘We don’t need them.’), and bakeries were the province of unmarried men, widowers, and bad mothers – after all, if a woman was not to spend her time baking for her family then she was obviously spending her time up to no good. The mores of Little Germany were deep rooted and utterly intractable. Had widowed Emilia Richter sought help in caring for her eight charges, as a recipient of charity she would have been both pitied and censured. Her crushing 20 hour work day, and emphasis on keeping her family together at all costs, were exactly what the community expected of her. “Her hands were rough, but her children were all clean,” words spoken by a neighbor in the days after her death, were as high an accolade in Little Germany as any imaginable. The same rigid belief in self-reliance, and refusal to take charity, remained even in the face of the greatest disaster in New York history. As documented in Ship Ablaze (O’Donnell), when it came time to distribute the large sum of money raised for the Slocum needy, not even the worst off showed up. Finally, the charity was organized in such a way that claimants could apply in complete privacy, safe in the knowledge that all records would be destroyed after the funds were distributed, eliminating any “shameful” evidence of just who petitioned for aid. When the beloved Reverend Haas attempted to use charity money for the benefit of St. Marks Church the reaction was so negative that he was eventually driven way from Little Germany.

12 year old John Klenck, of 113 St. Marks Place was, if possible, even less fortunate than the surviving Richter children. His father had died some time prior to 1900, leaving the support of his family to oldest son, William, who worked as a store clerk. Bertha Klenck, 40, and two of her three children, William, 20, and Charles, 7, were lost in the disaster.

As of 1920, John Klenck was unmarried, living with his widowed aunt, Anna Eichler, and her brother in law Fred Bayer at 804 West 180th Street. He worked as a credit investigator for a Trust Company. His date of death is not listed in the Social Security Death index.

‘I had to send my little Hattie away. She is all I have left, but she couldn’t go out on the street because everyone would talk to her about the boat, and she couldn’t stay in the house with nobody to take care of her. I would be in the river if it wasn’t for her. For years we struggled and struggled and we got things piece by piece.

‘One month ago we moved in here. I think it must have been for the funerals. My month is up now and I will have to go- I don’t know where. There is no one to make a home for me and my Hattie.

A 1904 interview with Mr. Fetzke of 211 East Fifth Street, husband of victim Gusta Fetzke, 38, and father of victims Elizabeth,14, and Herman Fetzke, 8 months. Hattie, 12, was the only survivor.

In spotless rooms lived the Rosenagel family, husband and wife, their little daughters, Lucy and Grace, and the old grandmother. Mrs. Rosenagel had promised to take the little girls on the Sunday school excursion if the day was fine. When the panic came on the boat, she was separated from her daughters and was lost.

‘She was such a good mother’ the little girls lamented, ‘always making nice things for us and giving us pleasure.’

As an evidence of her thoughtfulness, the confirmation dress that she had made for the older girl was pointed out with the remark ‘That’s all hand work. She did it.’

‘Ach, yes,’ moaned the aged mother of the dead woman. ‘I have had thirteen strong children and I have lived to see them all die but one. Who will take care of me now she is dead?’

Annie Rosenagel, of 129 East Fourth Street, was 43 when she died. Grace was 7, Lucy was 13, and her mother, Margaret Dressler, was 79. The 1910 census found the Rosenagel family living in Brooklyn. Charles Rosenagel, 38 at the time of the disaster, had remarried, and fathered two children, Margaret, 4, and Clara, 2, with his new wife, Margaret. Margaret’s aged parents, Peter and Margaret Christ were living with the Rosenagel family at that point.

I know Lillian did not die with my wife. My wife was drowned, but she looks peaceful and there is a smile on her face. She’d never have looked that way if she hadn’t known the baby was safe. Maybe Lillian was lost afterwards, but when my wife died the baby was safe. Her face tells me that.

Walter Peters

Walter Peters, 50 Avenue A. Helen Peters, 28, was issued death certificate #2982. Lillian, 1, was issued #3603, so presumably she was among the last found.

We left the Third Street Dock at 10a.m. I was polishing brasswork soon after, when a deck hand called my attention to smoke coming out of a forward cabin. IO ran forward, and helped the first assistant engineer to stretch a hose. We could not get any water. The fire spread so rapidly that we were driven to the forward promenade deck, which was covered with panic stricken women and children. I pulled down an armful of life preservers and distributed them. I then put a life preserver around my shoulders and jumped overboard with two children.

They were torn away from me by the impact of the water. I managed to grasp one of the blades of the paddle wheels and climbed up in the paddle box. The water beneath me was a perfect hell. Men and women were clawing at my legs as I climbed, and my trousers were torn away in my efforts to escape from them. I was subsequently rescued by a row boat and put on shore.

Peter J. Tremble, General Slocum deckhand

Charles Schwartz, Jr., 18 year old machinist’s apprentice, was one of the few General Slocum passengers proficient at swimming. His rescue of at least twenty-two of his fellow travelers earned him much praise in the press, ‘though he took pains to downplay it.

“I was on the hurricane deck of the General Slocum and when I knew there was a fire, the first thing I did was to put a life preserver on my little brother, Louis, who is ten years old and I got him to stand by me. Then I saw that there was going to be a panic and I thought that in the water was the best chance for him, so I threw him overboard. Louis is alright.

I noticed that two or three boats were coming, and I backed up against the rail, calling out that there was a good chance and pleading with the passengers to keep cool and not shove. I carried my grandmother to the rail to await the approach of some boat, but suddenly the rail gave way and with scores of others we were dumped into the water. In the struggle of the mass who were fighting to keep up, my grandmother was torn away from me

The first person I saw was Mrs. Adickes, who keeps a candy store and she called me by name and I went over and helped her by keeping her chin above water and towing her. She got to shore alright and was not much hurt. She threw her arms around my neck and kissed me. I got into the water again and helped Miss Emma Haas, the sister of the pastor, until a boat came to take her, and then I saw my mother and grandmother. They were floating face downward. I got them both ashore and helped the doctors with them on the lawn. ‘It’s no use’ said the doctors ‘we can’t do anything for your people.’

Then I looked out upon the water and saw that there were yet men, women and children who might be saved. A man came along in a little boat and I swam out to him and worked with him. I went overboard whenever I could and swam up with people and helped them into the boat. Many of them grabbed at me, but I was able to keep off enough to prevent being dragged down. I felt hands way down in the water holding at my feet. Hands caught me everywhere, and above me was the fire raging and roaring. We brought ashore many bodies, too, and not until there was no chance of saving anyone did I quit.

Hero? Oh, I’m nothing like that. I happened to have the knack of swimming a little better than some other persons and so I thought it was my duty to do the best I could. Besides, I’m not thinking much of that kind of thing with my mother and grandmother lying there in the room. I did all I could for them, but the smoke must have suffocated them before they were in the water.

“Mrs. Adickes” was actually Margaret Stuve (65) grandmother and chaperone of the Adickes children. John Adickes (15) and his adopted sister Margaret Heidekamp (12) were lost in the fire. Sister, Annie (8) survived. In the Slocum program for June 15th 1904, the Adickes’ business is advertised: E ADICKES Fine Confectionary and Ice Cream Saloon, 49 Avenue A, between 3rd and 4th Streets. The family lived upstairs over the store.

Despite the deaths of Louisa Schwartz (43) and her mother, Charles Schwartz’ family was luckier than most, for all four children aboard the General Slocum (Emily, 20; Charles, 18; Anton, 16 and Louis, 10, survived.

14 year old John Tischner, of 404 East Fifth Street, saved the life of his companion of the voyage, neighbor Ida Wytska.

I was down on the lower deck with Ida Wytska who lives in the same house with me. We were eating ice cream when the flames burst out right near us. Everybody seemed to be yelling ‘Fire!’ and I saw a lot of women with their hair and dresses burning jump into the river long before any boats came near us.

My friend was going to faint, but I kicked her in the shins and woke her up. Then I got a lot of life preservers, most rotten, and after a long time I got one on Ida.

The tugs were coming up near us then, and I told her to jump. She wouldn’t jump and I pushed her over. Then I jumped in the water and I got hold of her hair and I held her up until the tug came and we were pulled out.”

“As soon as I hit the water I started to swim out towards the center of the stream, but the tide was so strong I went back five strokes every time I took one, so I made up my mind I would not tire myself out. So I just turned over on my back and floated.

So while I was floating, they were jumping over the side of the steamer. Twenty would jump at once, and right on top of them twenty more would jump. Then there would be a skirmish of grabbing at heads and arms, and the fellows that could swim would be pulled down and had to fight their way up. Two women who got near me shouted for me to help them, and I tried to, but they were too big and I had to break away to save myself.

When I was in the water about half an hour they pulled me on a tugboat and chucked me up on the dock.”

Willie Keppler

Albertina Lambeck, 33, of 427 East Ninth Street, was observed by a reporter from the New York Times, at Lincoln Hospital. Her head was bandaged, and she was shrieking with grief over the deaths of her five children. This easily found reference has made Mrs. Lambeck one of the better known survivors. Here is her less well known personal account:

Albertina was fortunate. She later learned that two of her children, Herman, 14, and Dora, 11, survived by clinging to one of the paddleboxes. However, her other children, Ernest, 9, Henry, 6, and Albert, 3, were lost. Herman Lambeck, who was rescued by the launch Kills, gave this interview:

I was with my mother, two brothers and two sisters on the hurricane deck. We saw a lot of smoke and flames coming from below and mother got scared. Just then, Dr. Haas, the minister, came running up to us. He said it was nothing but some coffee burning, and begged us to be calm.

He then went looking for his own family. We all stood holding on to mother, and then the deck broke underneath us. I lost hold of mother and fell into the water. When I came up, I saw my sister, Dora, hanging on to the paddle wheel. I looked for her after I was picked up, but she had gone.

Mrs. Lambeck died, in Queens, NY, in 1930. Dora, who gave the name of Dorothy to the 1930 census taker, was unmarried and living with her father, Henry, and mother at the time of Albertina’s death.

John Kircher, of Brooklyn, when interviewed at the morgue, angrily declared

In addition to his daughter, Elsie, 7, John Kircher lost his mother, Catherine, 62, his sister-in- law Margaret, 34, and his nephew, Harold, 3. His 7 year old niece, Stacey, survived, as did his wife, Lizzie, 37, and his sons Frederick, 9, and George, 3.

My life was saved by clinging to a paddle blade while the fire burned around me, blistering my hands and face. I had lost my baby and was separated from my three other children, one of whom I have since heard from. When the fire started, I picked up my baby and told my other children to cling to me. I was close to the rail when a crowd of frenzied women and children forced us overboard. I was about to let go, for the blaze was right over me, when a rowboat came along and I was picked up.

Mrs. Antoniette de Luccia, 31, of 54 East Seventh Street, and her daughter, Rose, 12, returned to their building alive and uninjured. 54 East Seventh had the grim distinction of being one of the hardest hit buildings in the East Village. Among those lost were Mrs de Luccia’s children Agnes, 6, Frank, 8, and Nicholas, 4,(Nicholas was never recovered) Mrs. Sophie Siegal, who was pregnant, Margaret Clow, 40, Flora Galewski, 36, (never recovered) and her children Helen, 6, and Morris, 3. Flora Galewski was the equivalent, in 1904, of a day care provider for the working women of her block: she would take their children to Tompkins Square Park for the day and allow them to play as their mothers worked. Frank de Luccia was identified by a metal school I.D. tag sewn into his clothing. Louis and Antoniette DeLuccia appear, along with their daughter, Rosie, in the 1910 census. Rosie, at 18, was unmarried, and the de Luccias had not had any children in the intervening six years.

Eleanor Wiedemann Reichenbach, 23, of 241 Stockholm Street, Brooklyn, was on the middle deck with her two year old son, Herman Jr., when the panic broke out. Eleanor obtained a life belt and placed it on herself:

The life preserver caught fire. There was a rope hanging over the side of the boat, and I grabbed that. The rope also caught fire. The flames of the life preserver were licking my face. I dropped the baby into the water to prevent his clothing catching fire. He sank at once. That is all I remember. When I became conscious, I was in the arms of a Negro who had saved me.

Herman Reichenbach Jr. was lost. Eleanor’s only other child, a daughter named Madaline, was born in 1905.

Valentine and Magdalena Kolb were typical of the successful first wave of German immigrants to the US. Magdalena was born in 1832, Valentine in 1836. Both came the United States in 1853, where they met, married, and raised 5 children. By 1904 they had been married for fifty-one years. Valentine’s success as a barber had allowed them to move away from Little Germany to the solidly middle class Fordham Road section of the Bronx. But, as did most who left Little Germany for more upscale environments, the Kolbs maintained ties to the old neighborhood. The Sunday School excursion would have been a pleasant way for the old couple to catch up with friends and enjoy an atypical midweek day off. Neither survived.

Two brief accounts by passengers who owed their lives to the deaths of others:

Henry Ferneisen, 10

The Ferneisen family, of 40 East Seventh Street was exceptionally lucky; Emma Ferneisen, 33, and her three children Henry, William, 8, and Marie, 7, all survived.

Catherine Jordan

Catherine Jordan,20, of 37 Third Avenue, who survived with burns. Her sister Pauline (16) with whom she traveled, also survived with injuries.

One of the flotilla of small craft performing body recovery on the day of the fire, found the body of a 12 year old girl adrift in the river. It was tied to the craft, by a rope around its waist, and towed to the Bronx Shore with other bodies and brought to the Alexander Avenue Police Station, where it was tagged #24 and laid out on the floor with the bodies of other victims. That afternoon, one of the few “miracles” of the day occurred when the body convulsed, vomited up river water, and began to breath again. Clara Hartmann, 12, of 309 East Tenth Street, “Body #24” gave this widely quoted account:

I shall never forget when Mamma and sister said ‘God Help us!’ when they saw fire come up out of the front end of the boat, and the people, many of whom we knew, began to rush around. Mamma called me to her and she took hold of Margery’s hand and mine and she said ‘stay with me’. Mamma, Margery and I remained on the boat, still holding hands, until the flames got awful close and hot. Everybody was then jumping into the water, and as we did not want to get burned up, we decided to jump too. There were so many in the water near where we wanted to jump that we had to wait a while before space was clear, and then we all jumped together, still holding hands. But the moment we got into the water we had to let go of each other to do what we could for ourselves. Seeing Mamma and Margery struggling nearby, I tried to save them, for they were struggling awfully. Then a lot of swimmers got around us and we were separated. I heard Margery say again ‘God save us’ then she gave a gasp and sank out of sight. Mamma I didn’t see after that.

While I was keeping afloat a man came near me, and I grabbed him around the neck. He was awfully mean, for he tried to push me away, but I just hung on to him as hard as I could. He pushed harder than ever, and my head went under the water. Then I felt him sinking, and I let go, and I must have fainted. I don’t know what happened to me after that until I came to life, they tell me, in the Alexander Avenue station house, but I must have floated and been picked up by a boat. They told me afterwards that I was towed behind a launch, but I did not feel it. When I got out of my faint, it was in the afternoon, I thought it was yet morning. I heard men tramping on the floor and felt that I was lying on something hard and that my head was covered. Then there was talk about taking the dead people away and I remembered the fire and the people drowning all around me. I thought that I was still in the water too. My stomach got sick- I had swallowed a whole bunch of salty water. Then it began to gush out of my mouth, and a woman said ‘this little girl ain’t dead’ and she called ‘Doctor! Doctor!’ just like that. They pulled the cover off of my head, and I began to feel much better and the air came to me. They took me up from the floor and put me on a couch, and then I was taken to the hospital.

I cried when I remembered mamma and Margery, but the hospital nurses told me they were safe, but they haven’t come home yet.

Willie Reitz, my cousin, found me in the hospital and I was glad to see him. He is only thirteen, but he went around to all the hospitals looking for me, Margery and mamma, he told me when the nurses let him come to my couch. He hurried home, and they brought me clothes and took me here.

The miracle did not extend to Margaret “Margery” Hartmann, 15, or her mother, Mary, 45. Both were lost. Clara’s father, Jacob, 54, and older siblings Jacob Jr., 22, and Mary, 20, did not attend the excursion.

Clara Steur, whose name cannot be matched to any on the printed survivors list, spoke of the loss of the Mannheimer family:

I was sitting on the upper deck with some friends. They were Miss Mamie Mannheimer, Miss Lillie Mannheimer, her niece, and Walter, the latter’s brother, aged 11. We had just passed the entrance to the Harlem River, and were going slowly, when Lillie, who was looking forward, called to her aunt saying ‘I think the boat is on fire. Look at all the smoke,’ ‘Hush’ replied her aunt, ‘you must not talk so; you may create a panic.’

Lillie would not be silenced, however, and it seemed but a few minutes later that there was a roar as though a cannon had been shot off, and the entire bow of the boat was one sheet of flames. The people rushed pell-mell over one another and in the rush I lost track of my friends. Hundreds of people jumped overboard, being so caught by the flames that escape was impossible.

I began to dispense with my clothing, so that I would have a better chance in the water.  Then I started to climb down the side of the boat when I heard a voice calling to me to hold on a minute.

Then I started to climb down the side of the boat when I heard a voice calling to me to hold on a minute.

I turned and saw a man standing on the bow of a tug which was approaching. I held on, and was soon taken off with a number of other persons who had been rescued from the boat and from the water.

As I left the dock I saw, it looked to me, two hundred bodies, mostly women and children, along the shore, lying on the ground. Physicians were working over many of them.

36 year old Mamie Mannheimer, of 87 East Seventh Street, was lost, as was 11 year old Walter Mannheimer.

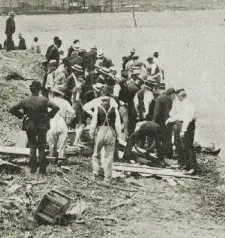

Heroic work by tugboats and harbor craft of all sorts saved the vast majority of the 350- 400 General Slocum survivors. The official government investigative report states that had it not been for the appearance of this impromptu fleet, the death toll would have approached 95%, for only about 70 people were pulled, or swam, to shore on North Brother Island. Dozens of survivors wrote of the miraculous last-second arrival of tugs that appeared through the smoke, sailed up close to the side of the vessel, and allowed passengers who were fortunate enough to be in the right place to leap down to safety.

Captain McGovern, steam launch Mosquito

Damn the tug! Let her burn! What’s a tug to a human life?

Captain James L. Wade, tugboat Wade

Wade ordered his tug, representing ten years of savings, grounded at an angle between the General Slocum and shore. At least 78 of the fewer than 400 survivors were able to use the badly damaged Wade as a bridge to safety.

I was sitting on the rear of the upper deck with Otto Hans and Albert Greenwall. We were just passing out of Hell Gate when I smelled fire. I looked toward the front of the boat and saw a big cloud of smoke. Otto, Al and I jumped upon a seat and grabbed life preservers. They were rotten and all the cork came out of them. Women and children were yelling around us something awful. Just then, a big blaze of fire came up through the center of the boat and the people began to jump overboard.

The first tug to reach us was the Director. It was a big boat, and came right up close as we were going toward the island. I jumped toward the boat, and a lot of people jumped on top of me. Half of them fell back into the water between the tug and the boat. In a minute there were so many on the tug that her stern was way down in the water. They kept jumping, and slipping off the tug and going down. I got hold of the leg of a little girl who was sliding off, and pulled her back, and then I sat on her to keep her from being pushed overboard.

When the other tugs came up everybody that was left tried to jump on them, and they jumped on top of one another. Lots of them fell off and were drowned.

The women and kids were crying and yelling so we couldn’t hear the men on the tugs, who were waving their arms at us not to jump. I saw men jump into the river long before the tugs came, and not one of them could swim. They all went down. I thought the Director would sink or turn over when she started for shore, there were so many on her. When we got off, we were taken in wagons to the elevated road.

George Gray, 13, of 309 East Fourteenth Street. His friend Albert Greenwald, also 13, of 326 East Fourteenth Street survived as well.

It is difficult to tell what to do in such an emergency as that which confronted us in the Slocum disaster. I had just left the Edson, which had come in at the Board of Health Pier at 132nd Street, when I heard five whistles from my boat. I was down there in a moment, and as I was going across to the Slocum the engineer yelled up that he had water in three lines of hose. We soon saw that water wasn’t needed, but quick work to save lives. Everything in the way of life preservers we had went overboard, and then the heaving lines.

Fifty feet was as near as I thought it safe to go, for although the windows of the pilot house were down in their frames, I could hear them crackling and the paint was blistering on the woodwork.

It was hard work in many cases, for there were several large and heavy women, whose weight was increased by their water soaked garments. We got all those who came our way. Some may think that we ought to have taken the rescued ashore right away for medical attention, but I considered it best to save as many as we could.

Captain Henry Rick of the tug Franklin Edson.

Mrs. White, the Superintendant of Nurses on North Brother Island, briefly described her role in the rescue efforts that morning:

As soon as the General Slocum came around the point, I sent back for cheesecloth and bandaging muslin. While Mrs. Smith and the nurses were busy bringing the victims to, I went back and got whisky and more bandages and cheesecloth. I tried several times to get out to the wreck but the heat was so intense I could not, until I put the skirt of my dress over my face. In that way I was able to wade out up to my knees. The call came for ladders- there was no one to go for them so I went. They were 35 feet long and dreadfully heavy, but we dragged them down to the water. I never could have done it if I had been in my senses. I did not know anything or feel anything.

I saw a boy and his mother drifting in. I lay down on the sea wall on my stomach and called out to him to hold on to his mother and I would get her out. He had his hand under her chin and was paddling along as best he could. She was unconscious and weighed, I should think, about 250 pounds. Somehow I got her over the seawall and kneaded the water out of her. She lived, I think. In reading over the list of injured I fancied the boy might be #47 in Lincoln Hospital.

As soon as the injured revived we wrapped them up in blankets and brought them up to the hospital. We stripped the place of blankets. The nurses had their shoes and uniforms destroyed by the mud and water, and torn to pieces on the rocks.

I hoped to find a first person narrative by heroine Pauline Fultz. This 1904 account is the best I have read:

Pauline Fultz, a comely 18 year old nurse employed in the North Brother Island Hospital flung herself into the water, swam into the midst of the struggling women and children, brought five little tots safely to shore, and then battled until overmastered by a powerful woman who dragged her to the bottom and from whose death clutch she escaped exhausted and helpless. She was pulled ashore by nurses, and carried to the hospital.When Dr. Stewart, the superintendent of the hospital, sounded the alarm, Miss Fultz was among the first to reach the beach. With the other nurses and men she waded into the water and helped ashore all those within reach.

Fifty feet away the surface of the water was dotted with the heads of struggling women and children. Some were making feeble efforts to keep afloat, others drifted helplessly, kept up by their clothing.

‘I am going out to them’ cried Miss Fultz, as she pulled off her shoes and skirts.

Several nurses caught hold of the girl and tried to restrain her.

‘Let me go’ she cried. ‘I can swim; I must go to their rescue.’

She flung the nurses off, and jumped into the water. With quick, strong strokes she soon reached a little girl. Taking the child’s hair, she turned and swam to the shore, delivering her charge to the nurses who waded out to meet her.

Then she turned back. She grasped another child and took the little one to shore. Notwithstanding the pleading of the nurses, she returned again and rescued another child.

Five times she reached the shore with her human burdens.

The sixth trip almost proved her last. As she passed close by a woman, who gave no sign of life, the latter’s arms suddenly clasped around the girl’s neck. Those on shore saw a short struggle and then both disappeared. They arose again, but Miss Fultz could not break the woman’s hold. Finally, she placed her hand under the woman’s chin and pushed her off. Before the woman could recover her hold, Miss Fultz had passed around and caught her hair and started to pull her towards shore.

When they were within a few feet of solid footing the woman suddenly turned and grasped the girl again, both sinking. Soon the girl’s body appeared on the surface. Her strength had been exhausted. She was dragged ashore more dead than alive and sent to the hospital.

‘It wasn’t anything to do’ said Miss Fultz, later, ‘What could I do? I saw the women and children struggling in the water, and what could I do but go to their rescue?’

‘I was after the children. I wanted to save the women, too, but my first resolve was to bring the children ashore. The woman who got me nearly took me down with her. If she hadn’t been so excited, I would have saved her. It wasn’t much to do. I learned to swim at Asbury Park last summer.’

The children Miss Fultz brought ashore were all unconscious, but they were quickly revived and will recover.

Miss Fultz nearly fell victim to the reflexive response to grab and to climb atop, that makes rescuing people in the panic stage of drowning difficult and occasionally lethal. More than a dozen Slocum survivor accounts were given by people who admitted that, in their terror, they had possibly drowned other people. There are considerably more accounts by those who had to fight their way clear of hands that grasped their necks, their clothing and their feet, as unfortunate fellow travelers reached the blind panic stage of drowning. Eleven year old Salome Klein recalled:

I was eating lunch when the fire started. On the deck where I was sitting with my basket some children came running and I heard shouts. Then somebody said ‘Fire!’

I dropped my basket and looked around for the family. I was left by myself. The flames came up and black smoke, too. I don’t think I was afraid. I don’t know. I just know that I ran away from the fire and when I got to the edge of the boat I heard everybody screaming and crying and I jumped into the water.

A man and a woman were in the water where I jumped. I caught hold of the man’s hair. He went under the water, then I grabbed the woman by the foot. She went down, too.

A boat passed, and a man threw me a rope, but I could not catch it and the boat went on after the others. I paddled near to a big rock. A man and a woman were on the rock. The woman held the man’s hand, and he held his leg to me, and I was pulled up on to the rock. Some of my clothes had been pulled off in the scuffle and the rest of them were taken off me. Then they gave me hot milk and took me to the hospital.

I was sitting on the upper deck with the two smaller children, and the others were playing around the boat. When I heard the cry of ‘Fire!’ I yelled for my children. They ran to me, and I told them to stay near me and they would be saved. I climbed over the railing holding the baby tight in my arms. Somebody loosened my hold on the stanchion. At that time a tug came alongside and I fell right on to its deck with the baby in my arms. The other children called after me, but when I looked up they had disappeared. I was taken to North Brother Island and from there came home. I got word that William is in Lebanon Hospital. I can only hope my other children are saved.

Mrs. Katherine Mettler

Mrs. Katherine Mettler, 32, of 338 East Fifth Street lost her children Elsie, 15, Albert, 11, Robert, 10, and Fred, 8. Her 4 year old son William survived, as did her two year old, George. Catherine and Robert Mettler had another son, Theodore, in 1906 and a final child, Arthur, in 1912. In 1930 the family was living on upper First Avenue, with Catherine widowed and working as a building janitor, and George, Theodore and Arthur Mettler all unmarried and all working as machinists in a factory.

Herbert S. Nulson, who witnessed the fire from the tower of the Delavergen Refrigerator Company factory, at the foot of East 138th Street, gave this description:

I looked down the river and saw the steamboat which I was sure then was the General Slocum. The flames were just beginning to make headway when I first saw her, and by the time she came opposite us I could see that her decks were crowded with women and children who began to jump into the water.

I looked down the river and saw the steamboat which I was sure then was the General Slocum. The flames were just beginning to make headway when I first saw her, and by the time she came opposite us I could see that her decks were crowded with women and children who began to jump into the water.

Tugs began to put out to the burning boat, but they could not get near enough to do any good on account of the heat and the flames.

A lot of rowboats had put out by this time, and those, with the tugs, went as near the General Slocum as they could, but the water was so full of bodies that they made their way only with difficulty and the smaller of them were in danger of being swamped by those trying to climb over the gunwales.

I saw one tugboat push right up through the smoke and flames. She had a long, flat, empty barge in tow and I suppose she ran this against the Slocum and took off many people in it.

When my Great-grandmother died, there were at least 10 General Slocum survivors still living. An issue of Disaster Magazine, from that era, had a surprisingly tasteful (considering the venue) recounting of the fire and interviews with four of the survivors who attended the memorial service at the Lutheran Cemetery in Queens – Minnie Muller Rolka, Martha Stricker Dietz, August Hauser and Edna Doering. A haunting view of the Slocum I’ve not seen used since appeared in an American Heritage article around the same time, but most of the coverage of the General Slocum disaster in the 1980s would come in conjunction with a survivor obituary. The best, by far, work about the Slocum during that time came in Jeff Kisselhoff’s 1989 work You Must Remember This: An Oral History of Manhattan From the 1890s to World War II. Among the book’s many highlights was an interview with survivor Edna Doering, who gave an exquisitely detailed account of the nightmare that claimed most of her family. Edna escaped easily from the General Slocum, but her brother Gustav, 9, and sister, Ida, 11, died in the river. Her badly burned mother was brought home to die a protracted death in her own apartment, during the course of which, Edna recalled, she called for the two children who died, and did not understand why they would not come to her. Gustav was recovered quickly, but Ida was missing for a time, and when she was found her body was brought back to the family apartment in a coffin.

The first truly outstanding General Slocum book, Ship Ablaze, by Ed O’Donnell, was published in 2003, to excellent reviews. The book, a well-done television documentary, and the 100th anniversary of the fire helped elevate public awareness of the disaster to the highest it had been in decades. Minnie Muller Rolka had died in 1986, Edna Doering in February 1992. Catherine Gallagher Connolly, who lost her mother, Veronica, brother, Walter, and infant sister, Agnes, in the fire, died at age 107, the next to final General Slocum survivor.

By the fall of 2003, only Adella Liebenow Wotherspoon remained of the 378 known survivors. Ed O’Donnell generously sent me copies of some fascinating Slocum reports from 1905, and even more generously, provided me with an address and phone number for Mrs.Wotherspoon after being told of a project with which I was helping my friend Anthony Cunningham. Anthony made contact with Adella, who audiotaped her Slocum-related memories for him. The tape arrived shortly before her death in early 2004, and the interview may well be the last words about the General Slocum spoken by a survivor. Excerpts from Mrs. Wotherspoon’s audiotape:

It was a real family occasion… It was rare in those days to get so much time off work so the adults must have been looking forward to the trip immensely. Later on my aunt said that everyone was so happy boarding that boat. She said everyone was laughing and talking and the children were romping about. The weather was beautiful and it looked like it was going to be a wonderful day out.

It was a real family occasion… It was rare in those days to get so much time off work so the adults must have been looking forward to the trip immensely. Later on my aunt said that everyone was so happy boarding that boat. She said everyone was laughing and talking and the children were romping about. The weather was beautiful and it looked like it was going to be a wonderful day out.

It seemed that my parents didn’t notice the fire for a while. There was a big puff of smoke which startled everyone but someone said it must have been something burning in the kitchen and they all just laughed it off. But then there was a sheet of flame which appeared from nowhere and everyone panicked.

The life preservers were hung about eight feet above the deck and my father recalled seeing dozens of people reaching up desperately trying to get them, arms straining. He said that many of them were actually wired in place and it took some time to pull them free.

A few men were trying to free up some of the lifeboats but again they wouldn’t budge because they were tied down and secured with wire. Nothing they could do would shift them so they had to simply leave them.  My father said the speed with which the decks were burning was incredible, but even so he saw some people actually rushing into the flames trying to find their children.

My father said the speed with which the decks were burning was incredible, but even so he saw some people actually rushing into the flames trying to find their children.

I have no idea how I was saved – it was a miracle really. My mother had held me in her arms and jumped onto a tugboat that had come to our rescue. Her left side and arm were badly burned where she had shielded me from the heat. She was put down onto the beach at North Brother Island and sat there in shock. There were bodies floating about in the water and more bodies laid out on the beach. She had no idea what had become of my father…

The body of my sister Anna was later found – but Helen, my other sister, was gone – missing forever – as was my cousin Emma. Some time later my cousin Frank’s body was recovered, but he was barely recognizable and was only identified by his clothing. He was buried in the family plot.’

The whole of Little Germany went into mourning. Nearly everyone was affected by the tragedy because it was such a small tight-knit community.

Complete interview available in:

Thanks are extended to Ed O’Donnell for trusting us enough to provide us with Mrs. Wotherspoon’s contact information. Gratitude is extended to Craig Stringer for providing me with the “missing” name of Emilia Richter’s son who did not attend the excursion. Thanks, as well, to “the usual suspects” who I can always count on for help, advise, and unbiased critique not at all hindered by the scientifically proven fact that I am always correct – even in the face of unimpeachable evidence that I am not. So, Mike, Marty, Tim, Anthony, Harald, Brian, Peter, Zoomer, Kyle, I look forward to the next installation of Gare Maritime and many more enlightening conversations.

We had a party of eleven on the boat, and were anticipating a fine day’s outing. We wanted to hear the music on the way up the river and so all of us were gathered on the after deck, not more than twenty feet away from the band and close to the rail of the deck.

The first intimation we had that there was something wrong was when a scream came from the forward part of the boat. We concluded that someone must have fallen overboard and began scanning the water in the wake of the boat. But we did not have to wait too long to find out what the real trouble was. A few seconds after the first scream there was a general panic on the forward deck.

We could hear the women and children screaming, and an instant later there was a puff of smoke and flame near the bow of the boat. I realized then that we were all in the gravest of peril and that if we expected to escape with our lives some of us at least must keep our cool heads. In our party were my daughter, Annette, my son-in-law and daughter, Mr. and Mrs. Henry Schnude and their two little children, and my daughter Mrs. Frieda Toniport and her two children. In addition to these nine, there were the father and mother of Mr. Schnude.

The moment I saw the flames I called all of our party together and told them quietly that if we were to escape alive we must stick close together so as to be able to help one another. I thought that the strong among us could take care of the weak. But my words of warning were not more than out of my mouth when there came such a rush of panic stricken people to the stern of the boat that no human being could have stood up against it.

I clung to the rail and managed to hold my place, but when I looked around not one member of my family was to be seen anywhere. They had been whisked away from me in the rush and I did not know what had been their fate. By that time there were scores of women and children in the water.

At last I managed to get a foot upon the rail by clinging with my hands to a post. From that point of vantage I watched the crowd in search of my loved ones, but they were nowhere to be seen. Just then I saw our Pastor, the Reverend Mr. Haas, with his wife and daughter at the other side of the boat. He was trying to protect them from the trampling crowd. Then a minute later I saw them climb over the rail and all jump into the river together.

I took another careful look around to see if any of my family were on the boat, but still they were nowhere to be seen. Then I decided to take my chances in the water. The fire was so near that my hands and face were scorched and blistered and there were holes in my clothing that had been burned there by the flying sparks.

I climbed over the rail and jumped feet first into the water. It seemed to me that I sank hundreds of feet and that I should never come to the surface again. But at last I saw a flash of light, and that told me that I was up where I could get a breath of air. I tried to keep myself from sinking again by striking out blindly with my hands and feet, and did manage to keep up for a few seconds.

In that brief time I saw women and children around me in the water. They all seemed to be drowning. I remember I wondered in a dreamy sort of way if any of my children were near me, and if they would be rescued. Then my strength failed me and I sank once more. I stopped struggling and didn’t seem to care any longer whether I ever rose to the top or not.

Just then my head struck against something hard. That aroused my senses and I grabbed at whatever had bumped my head. I caught it with my hands and held on. Once I got a breath of air, my strength came back a little and then I discovered that I was clinging to the paddlebox. I held on desperately and a minute or two later a man in a small rowboat pulled up close to me. The boatman held out an oar to me and yelled to me to grasp it and hold fast. I did so, and he soon hauled me aboard his boat. I begged him to look for the other members of my family, but he had as many in his boat as it would hold and had to go ashore.