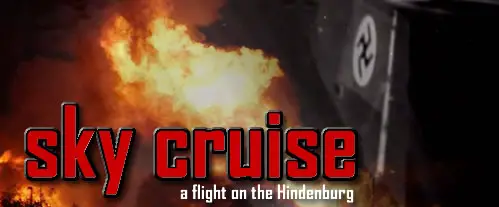

Sky Cruise : A Flight on the Hindenburg

A unique photographic and documentary record of the tragic airship.

|

Additional Galleries |

Family and friends awaiting the delayed arrival of the Hindenburg on her first crossing to the United States of the 1937 season may have kept themselves occupied reading this article in the May 8th issue of Collier’s Magazine. Few knew the Hindenburg during her brief life on the Transatlantic run; Ancestry.com shows 597 passengers carried on ten westbound crossings in 1936 (many of which are duplicates- for instance, Joseph Spah, who survived the final voyage, has three entries for that crossing, as does fellow survivor Peter Belin) and this article is, so far, the best extended account of life aboard the ill-fated Zeppelin I have found. Jim Kalafus

The Sky’s our ocean. If you doubt it, take a transatlantic dirigible ride. You’ll be reminded of an ocean voyage- with the rolling and pitching left out and the time cut in half. It’s punctual and methodical, but don’t think it’s not exciting- and it’s a foretaste of the future as well.

By W. B. Courtney

Three months before you had gone to the company’s office in New York and they had told you that on the evening of October fifth, at seven-thirty o’clock, der luftschiff Hindenburg would sail from Frankfurt-am-Main on her last voyage of the season to New York.

You laughed at their Teutonic cocksureness, and said why not 7:10 or 7:53, because you know that even the Normandie is delayed sometimes by river conditions or a passenger who forgets his tickets and must run back for them.

They repeated, tartly, seven-thirty.

Now it is three o’clock in the raw afternoon of Monday, the fifth of October; and you are in Frankfurt. Rain squalls brush the pine-covered Hessian plains. You stare into the forbidding wrack, and figure they won’t start tonight. The Zeppelin officials are checking tickets in the Hotel Frankfurterhof. It is not difficult to pick out in the lobby those who are to be your airmates. Each has the furtively resolute expression common to men about to go on long journeys. You look for thrill hunters, but find ordinary well-fed people; a group you might duplicate in the smoking room of any first class liner; Americans, Germans and English chiefly, with some from lesser countries, and several titles, and a Jap diplomat as well.

Everything is being cleared now: tickets, baggage, customs. You think –oh, this is German thoroughness and foresight to make sure you won’t delay the Hindenburg: but who is going to repair that threatening weather?

In the customs and ticket rooms, affairs move with courtesy and dispatch; the baggage room, on the other hand, resounds with protests and groans. You are permitted only 20 kilos (about 44 pounds) on the Hindenburg free; over that 5 Marks per kilo – virtually $1.00 per pound. You thought you had pared your stuff to the limit: but the scales of the pan-faced baggage meister seem to have assumed the responsibility of making Germany debt-free. Before you know it, you have paid $25 excess. This makes your passage come dear; $425, or $150 more than you paid for a nice cabin alone on the Normandie coming over, with nothing said about baggage. On the Hindenburg, you will have to share your room or pay double.

Soon the baggage truck rumbles away into the murky street, leaving you to contend with another point of difference between airship and steamer ocean travel. You are told you had better get your dinner in town: it will not be served on the Hindenburg, in spite of the early departure hour. The over generous larders of the steamer, from which they press food upon you at every turn are years away from the air; on the Hindenburg, there is no luxury weight, and in other amenities as well as in food you never quite feel you are getting all you paid for.

At six o clock to the dot large busses draw up at the hotel door and you all crowd in and start for the flughaven which is far across the river main to the southwest, beside the village of Mitteldick.

You veer off the main road, bump through a pine grove, and there is the huge Zeppelin dock, blotting out the horizon of the autumnal night. Its black mass is suddenly transfigured into a vision of brilliance and imagination, as the great doors are rolled apart, exposing the Hindenburg like some captured fantastic whale of outer space. You are herded through a side door, lined up for a final passport stamping; then shooed out upon a cool floor. You think, what a queer ceiling, how much like the ribbed hide of a starved horse. Then you realize you are walking under the belly of the ship in which you are to fly from Europe to America.

Here, for a few moments, the likeness to ocean sailings is sharp. Urged along by uniformed pages, you climb a gangway manned by smart young officers, and step into a bright foyer, where there is a happy confusion of messengers with last minute gift flowers and harassed stewards and passengers asking which is the way to Cabin 17, and one American journalist wanting to know if the bar is open yet. Before they can tell you, everyone rushes to the promenade decks on either side. Unconsciously, perhaps, you have listened for a whistle, or waited for a sense of motion: there has been neither, and had it not been for this sudden desertion of the foyer, and the sight of girders slipping past the windows, you would not have been the wiser.

You look at your watch. It is precisely five seconds past 7:30 o’clock.

You elbow to the airship’s equivalent of a rail and hang from the windows, shouting to friends lined up below. Many of them run alongside as the ship is “walked out.” They wave handkerchiefs, scream, gape, stumble: this is the last point of resemblance to ocean sailings. There is not a quiver to the ship, but now you are outside in the gusty night- good lord, is no one paying attention to the weather- and you are a nervous fellow!

There is a group of American naval officers aboard, making the round trip as guest observers.

You watch the scores of well-drilled Germans who, grasping drag ropes, sedately march along under the ship as it is pulled far, far across the field by the portable mast to which it is moored by the nose. Forward movement seems to stop, and a muffled hum from far aft indicates the four motors have been started. Though you strain your ears and eyes, you see no confusion and hear no orders.

“Up ship!” the American naval officer at your elbow says, to himself: and, looking at the spotlight thrown upon the ground from the control gondola-somewhere forward under the belly- you are aware it is growing more faint. The Hindenburg is rising, and if you had your eyes within the cabin you would never have known it.

Strong gusts are blowing directly toward the hangar, and you begin to wonder if you’ll clear the huge building. It is sliding near awfully fast. Then comes a slightly perceptible inclination of the ship, forepart up perhaps five degrees, barely enough to make a full tumbler spill over; and the propellers begin to bite. You move away from the hangar- off ueber Land und Meer, for the other side of your globe.

This flying business is complicated, in Europe. A silly mixture of spy hysteria and envy keeps France and England from permitting the Zeppelins to fly over them. Indeed, if a couple of other nations ruled likewise, the German airships could reach the outside world only by the ship route from the Baltic to the North Sea. Tonight, however, you go north over the hilly Rhineland.

The observation windows, lining both sides of the airship, are slanted towards the keel, giving you a view downwards. They are open, and everyone hangs out to watch the spotlight pencil a radiant track; it comes to be a game to see what will be captured next in its brief moment of illumination- a barn, house, tree, wagon. At nine o’clock there is the thrilling view of Cologne, with its magnificent cathedral, and from your altitude of only 500 feet a clear view of folks pausing in the street or leaning out of apartment and street tram windows; and you can hear their halloos. Over Holland, your gondola light paints circular rainbows on dark canals and swamps, and you can hear dogs barking in the farmyards; it is the last sound of Europe that comes to you. for soon you pass Vlissengen- being duly scrutinized by the searchlights of the Dutch fortifications there- and out over the North Sea.

It grows late, but no one thinks of bed. You turn from your window vigil to enjoy a cold bottle of Liebfraumilch: and suddenly a terrific roar and vibration fetches everyone palely upright. A grinning young officer hurries into the lounge: “The night mail from London for Cologne just passed overhead” he says. Now you are heading south by west down the Channel, and when you go to the window again it is to look down upon very rough waters. A big three-stacker is rolling so that you feel sure water is going down her funnels; a flotilla of British light cruisers at night maneuvers stabs you with a dozen searchlights. From Calais, on the one side, and Dover, on the other, French and British military planes come out to fly and dive and fool around you, to play at war. The German crewmen regard this sourly: they know that a slight mistake, a bit of faulty judgment, might send one of those planes rocketing into our hull, turn us into a fireball in the night. It is playing too closely with inflammable hydrogen- and the lives of seventy-odd persons: you are glad when they tire and scoot home.

Six hours out of Frankfurt, and there is nothing under you but the empty Atlantic, nothing over you but the now clear sky. You go to bed, while the Hindenburg drops the old world behind the moon.

Six hours out of Frankfurt, and there is nothing under you but the empty Atlantic, nothing over you but the now clear sky. You go to bed, while the Hindenburg drops the old world behind the moon.

Snug upon a mattress of air cushions, warm under a German “feather bed,” you wake to your first day in the oversea air. If you anticipated sensations of motion, you might as well have stayed in your own little trundle at home. You lay there in the gloom and find it difficult to convince yourself that at this very moment you are really flying above the Atlantic Ocean. There is no jolting, or sound, from the distant motors. None of the “handgrips” of ships; none of the stomach-curdling vibration of a fast liner’s propeller shafts. Indeed, you will have to watch vigilantly- using the horizon or a cloud for a reference point- if you are to detect the slightest rolling or pitching in even the bumpiest weather.

Your roommate in the berth underneath- a British Army captain- is awake and switches on the cabin light. “Oh,” he moans, “I was born a generation too soon. It rips me to remember all the days I’ve spent on passenger ships and transports, all over the globe, horribly, wretchedly ill. God sent this blessed windbag into the world for miserable sailors like me who can’t step on to a moored ferry without becoming seasick.”

There isn’t enough space for the two of you to dress at once- so you lie there and look the room over. It is small, compact, rather primitive; equivalent, say, to what you would get in third class on a moderately good cabin liner. You can unpack only fundamentals; your suitcase remains closed under the lower berth. There is a campstool, a shelf-table that folds against the wall, two rows of hooks, a celluloid basin that also folds away. The mirror and lighting are pronounced inadequate for primping by most female passengers. You don’t get much but speed for your $400. Yet, this reflection seems captious- it is true that you are cramped, but you are comfortable; and with the tolerant fervor of a true pioneer your remind yourself that the Mayflower pilgrims slept on board shelves and rag piles on the bare inside hull.

So, you get up and march to the badzimmer on the deck below. The shower nozzle looks big enough to rinse all the Hindenburg’s passengers in a group; but the steward morosely warns you that, regardless of how your soaping has progressed, the wasser shuts off automatically when the indicator comes to here, no. There isn’t margin for wasting in any department of life on the airship; everything is fold, scrimp, fluff. You can lift any chair aboard in the crook of your little finger, and even the aluminum piano in the lounge can be hefted by an ordinary two-handed man.

The passenger quarters are located one third of the distance abaft the nose, and a third of the depth up from the keel. They are arranged in a virtually square area enclosed within the shell, extending fully across the ship, and consist of two decks.

Deck A is the main deck, and the one in which you will spend the most time, unless you are a barfly. On the port side, Deck A includes the dining salon which, between meals, serves for an observation lounge; also, the wholly electrified galley and the wine cellar. The lounge is completely windowed on its sea face, so that you can look down as you walk or loaf. In the wide counter, on which you lean to hang out the windows, there is set a relief map of the intercontinental routes.

The “beam,” that is the width from side to side, of Deck A is about the same as that on a ship like the Washington. To cross, you go through a foyer where you will find the familiar “ship bulletin” with radio news dispatches (in German) and a chart with a small flag marking your latest position. This miniature does not remain static, from noon to noon, like those on shipboard; but advances with miraculous leaps from hour to hour. Off the foyer, along two corridors, are staterooms, all “inside.” There are twenty-five, each with two berths. From the foyer, a stairway leads down to B Deck. On the starboard of A Deck are the music room and reading lounge, library and writing room, and observation windows duplicating those of the port. If you want writing paper, you must buy it from the steward; and if you want a book (all in German) you must hunt for him to unlock the case.

B Deck, directly under A Deck, is not so commodious due to the inflare of the great shell. Here the observation windows are more deeply pitched; you don’t have to bend over to look straight down. On the port side are the shower baths and cabins for the officers and observers. On the starboard, the combined bar and smoking room; fireproofed and elaborately protected. Inside, the air is kept at a higher pressure in order to repel any stray hydrogen that might drift into the vicinity. There is a double entrance, and a steward in a kind of sentry box. You ring a bell; he admits you to the ‘lock” and closes the first door behind you before he opens the door to the smoking room proper. In there, an electric lighter is available, no matches. Indeed, when you came aboard you had to surrender all your matches, and your automatic lighter, too. The latter will be returned to you at Lakehurst. When you come out of the smoking room, you must close the door behind you, then stand in the lock for the scrutiny of the steward, who makes sure that you are not carrying out lighted cigarettes.

After breakfast, Captain Lehmann comes to show you around the Hindenburg. The first object you observe, as you step out of the dining lounge, is a bust of Hindenburg over the foyer staircase. Forgive your aging reporter a little gossip, but everyone should know that among the reasons stubborn Doctor Eckener- the ancient mariner of the skies- got into disfavor with the Nazis was his refusal to name the ship “Hitler” and to put Der Fuehrer’s emplastered likeness where the marshal’s now broods.

Down to B Deck, and then one more short descent and we step through a bulkhead door into the duralumin bowels of the vast ship. Through a ventilator slit in the outer shell at our feet we see the Atlantic, 800 feet directly below, and it has the appearance of diluted mil in the dawnish light. We step upon the extremely narrow catwalk which runs just inside the belly of the airship, from nose to rump. This is really a duralumin plank laid atop the keel girder, and though the ship is steady you need a sense of balance to negotiate it without fear or mishap. There is a guideline in some places; elsewhere not a thing to hold you as you walk in a forest of bright metal girders. Along most of the shell, however, is a maze of wires that seems adequate to net you if you should topple. The Hindenburg is 811 feet long, so that when you have walked dangerously to her rear end- and descended into the great fin to inspect the duplicate emergency controls there- then forward to the very nose, and returned amidships to the B Deck gangway, you will have covered almost one third of a mile.

Down to B Deck, and then one more short descent and we step through a bulkhead door into the duralumin bowels of the vast ship. Through a ventilator slit in the outer shell at our feet we see the Atlantic, 800 feet directly below, and it has the appearance of diluted mil in the dawnish light. We step upon the extremely narrow catwalk which runs just inside the belly of the airship, from nose to rump. This is really a duralumin plank laid atop the keel girder, and though the ship is steady you need a sense of balance to negotiate it without fear or mishap. There is a guideline in some places; elsewhere not a thing to hold you as you walk in a forest of bright metal girders. Along most of the shell, however, is a maze of wires that seems adequate to net you if you should topple. The Hindenburg is 811 feet long, so that when you have walked dangerously to her rear end- and descended into the great fin to inspect the duplicate emergency controls there- then forward to the very nose, and returned amidships to the B Deck gangway, you will have covered almost one third of a mile.

The walk is covered with rubber sheeting, and you must wear sneakers for the trip. You notice the officers and crewmen you pass, about their duties, all wear felt or rubber overshoes. These are precautions to avoid static or sparks; you can’t fool with hydrogen, and the Germans don’t. Those whose duties take them up to the topside of the ship, between the gas cells, are wholly clad in asbestos suits which have no buttons or metal that might give off the faintest spark; and the ladders are all rubber-shod.

The motors are Diesel; they require no ignition, and they use crude-oil fuel that won’t burn even if you touch a match to it. The storage tanks are arranged on either side of this bottom catwalk; whereas any hydrogen gas that might leak from a cell would collect at the top of the shell,146 feet- or as high as a 15 story skyscraper-above. The Germans use hydrogen because it has greater lifting power than helium and makes the Hindenburg more profitable; moreover, the United States, owning all the practical supplies of helium in the world, although they do not use it themselves, won’t let anybody else use it, either. The Germans are experimenting with a secret compound- some other gas added to hydrogen, which does not diminish the buoyancy value of the latter but does render it noninflammable. It is hoped this may be available soon. If so, the greatest risk of Zeppelin travel will be licked; and the United States can have its helium, for all the rest of the world cares.

Meanwhile, a novel arrangement in the Hindenburg reduces hydrogen peril. Each of the sixteen huge cells that store the gas which lifts the Hindenburg are “double” composed, that is, of a balloon within a balloon. Each inner balloon is filled with hydrogen. The outer balloon would be filled with helium, if it could be obtained. Thus the inflammable hydrogen would be insulated with noninflammable helium. For the present, the outer shell is gasless; and the insulating value is of space only.

From the keel walk you now make a side journey, halfway up one side of the shell, between the bottoms of two huge gas cells which sag and billow like the paunches of very emaciated and very old elephants. You come to a big opening in the side, and look down into one of the motor gondolas, suspended far outside the main shell. One man is always on duty in a gondola, to which access is had by scaling a ladder across open space. Each of the four motors is a Mercedes-Benz, and capable of 1,100 horsepower. A spare motor is slung in the freight compartment within the shell; and two small fifty horsepower Diesel-electrics provide auxiliary power for cooking, lighting, refrigeration and radio.

You return to the keel and see the freight, baggage, express and mail. Automobiles have been carried in here; while airplanes may be hooked on and drawn in through a great hatch when a passenger service to way stations is inaugurated in the future.

Now your catwalk is going up, up, up hill- an arduous climb, until you come at last to the very nose. This is where the mechanism that hooks the dirigible to a portable mast is located and operated. There is a nook here with ropes, gadgets, and telephones to the control gondola; also, an observation window for the use of lookouts during flight. Nothing outside but the boundless sea and sky. Inside, a homesick German sailor boy with a mandolin. He puts it behind his back, sheepishly, when you come up with the Captain. Then, at a word from Lehmann, he sits down again and when you turn away her resumes his playing of lieder.

“Student” explains Lehmann with a grin. “We have many in the crew. We Germans are breeding generations of airshipmen, just as the nations have bred generations of seafarers. Our chief steward has been with airships twenty-five years; your bedroom steward twelve years.” It is difficult to believe that this small, frail, exceedingly shy Captain has been in the dirigible service himself since before the war; that he was one of the hardiest and most daring of the Zep commanders who dropped bombs on London, a holder of all of Germany’s highest decorations for valor.

You gather this supply of trained airshipmen is one of the reasons Germany can fly dirigibles safely and others- including the U.S.and England- cannot. Further, that German adherence to the wise old theory of one step at a time has been of major importance. The Hindenburg is known in the Zeppelin factories as “LZ-129” LZ stands for Luftschiff Zeppelin. The numeral is her serial number of her design.Only 119 Zeppelins have been actually constructed. Each Zeppelin has been merely a refinement over the preceding one; not a departure from it. The Hindenburg is merely a better Graf; and the L-130, now being built for the Atlantic trade, is an improved Hindenburg.

Our Shenandoah, Akron and Macon, on the other hand, in the brash American way, set out to back new design trails; these were to be “radical improvements” over the German ships and many people more confident than experienced, contributed notions to them.

If German success with dirigible operations has been due to prudence, the actual winning by lighter-than-air of a major place in that nation’s air programs is a fine human story. Count Ferdinand von Zeppelin, sixty years old, and pout away on the Army shelf with the rank of General to gather dust in peace, startled and amused all of Germany in the late ‘nineties by constructing the first rigid “dirigible”- or steerable balloon. His first ships were downed, but the old Count wasn’t; and with the new century official Germany quit laughing and began to contribute funds. Hugo Eckener, young writer on the Frankfurter Zeitung, remained unconvinced and denounced Zeppelin’s experiments as gross wastage. The exasperated Count got into his coach and four and sought Eckener’s home. Zeppelin’s first irate gesture knocked the contents of a flower vase on to his silk hat. Laughing, both firebrands sat down; became friends; and in 1906 the erstwhile critic became First Pilot of the new Zeppelin company.

Count Zeppelin, who thus broke all precedents for Generals by amounting to something after he retired, was practical too; he began carrying passengers for money in his earliest models, long before the war and airplanes did the same. German dirigibles since have flown nearly one million passengers without a fatality. (Italics in original text- J.K.)

And it is the firm conviction of this skeptical reporter, after close firsthand watching of their methods, that only a stroke of war or an unfathomable act of God will ever mar this German dirigible passenger safety record.

Halfway back from the nose towards the passenger quarters amidships Lehmann turns off the catwalk and lifts a small trapdoor; you go down a ladder and you find yourself in what might pass for a sun porch. This is the control gondola, faired into the Hindenburg’s abdomen. It is divided into three compartments, with glass between. First is the “bridge;” then a chartroom; last, a weather cubicle.

In the bridge room you might be on a ship. There are the usual watch officers, navigation facilities, full service radio directional finders. Then you see a marked difference; two helmsmen instead of one. The first man stands looking ahead, and he keeps the airship on its course. The second, behind him, faces the side of the ship, with his right shoulder in the direction of travel. He is the “elevator” man. There is an inclinometer for him to watch, of course; but he keeps his feet wide apart, the idea being that he can instantly feel the inclination of the long ship, rising or falling in the variable air currents, and correct for it in the controls, thus aiding the smoothness of the ride. It is well known that veteran helmsmen of surface vessels build up an instinct for easing their boat along, regardless of instrumental aid. The Germans are breeding a similar race of sidewise helmsmen.

Also different from ship bridges is the row of dials that give pressure conditions in each cell, and there are certain other distinctive features; but these are technical matters which I don’t understand and couldn’t explain to you if I did; so we shall pass back to the weather room, for here always there is something going on that laymen can grasp. Indeed, this might well be called the “game room” for it is fascinating and continuous play and gamble with the elements.

The Captain has on the partition in front of him a grand chart of the North Atlantic. On it are marked little circles with letters which represent the positions and radio calls of every ship at sea.

The Hindenburg gets frequent weather reports from every one of those ships and from land stations. The Captain may build up a graphic picture of the whole Atlantic. The fastest liners, on their best days, need only be immediately concerned with the 600 miles or so ahead; but the Hindenburg spans virtually half the ocean in twenty four hours. Its weather chart must not show alone conditions ahead, but on each side, not only the present situation of the hour, but trends. On the Hindenburg’s weather chart, therefore, the high and low pressure and storm areas, the wind velocities and directions of a third of the globe are posted, and kept refreshed.

The Captain, plotting his run, stands in front of this map and plays it as he might a chessboard; shifting his course a trifle this way to avoid a fog patch, that way to avoid adverse winds on the south rim of a low-pressure area- veering north to gain the counterclockwise side of a storm. This is one of the most important advantages of air travel; flexibility, due to its great reserve of travel range. On the last westward trip of the Hindenburg before this one you are now on, she approached the North American continent while the vicious equinoctial hurricane of September beat upon New York and the whole Eastern seaboard.

Weather areas move in circles, against the clock. Captain Lehmann’s game board showed the northern edge of the hurricane mass, as it moved up the Atlantic, was near Greenland. Owing to the complexities of Great Circle navigation, a route from Frankfurt to Lakehurst by way of Greenland is only about 200 miles longer than one along normal ship lanes. The Hindenburg’s passengers, therefore, were presently thrilled to see the ice mountains of the Arctic continent under their starboard observation windows. Here Captain Lehmann, exact in his calculations, picked up the counterclockwise movement of the hurricane that was causing untold damage on land and sea, and the Hindenburg went booming down the coast of North America, riding the fury of the storm at 200 knots per hour without quiver enough to overslop full cocktail glasses at the bar.

You learn there is a possibility we may break the westbound-or “uphill,” as flyers call it because of the prevailing contrary winds- record of 52 hours on this voyage. Why is year-round Hindenburg service to New York not maintained? You ask. Because with present aeronautical knowledge, it is too risky to fly dirigibles into northern ports in winter on account of the danger of ice forming on the shell. An ice encrusted Hindenburg would be as flyable as a three for a quarter can of beans. Perhaps Miami will become the North American cold-season base.

Some of the American Naval officers whoa re making this trip aboard join you. They are grand fellows, and you feel sorry for them- every American who crossed on the Hindenburg last summer felt sorry, and a bit ashamed, on account of the American officers who made each trip, in groups of three or more, as guests of the German Zeppelin company. These fine, enthusiastic, officers of the American Navy have no chance to gain practical lighter-than-air experience unless by the courtesy of Germany.

The talk, naturally, turns on America’s lighter-than-air policy; the United States Navy’s disastrous experiences with dirigibles; the ability of the Hindenburg to “resell” dirigibles to America. Someone points out it cost eight million dollars to build the Akron and the Macon in America, and only about $1,250,000 top construct the larger and better Hindenburg in Germany. “The old excuse about the difference in living standards between American and European workmen doesn’t cover that margin! Trouble is, there’s too much politics and greed for quick profits in America, and too little thought of sound future possibilities. Too many patriots and too few practical men.”

The old Graf Zeppelin, with her top speed of 73 miles, has done more than one million miles of passenger service since 1928; more than an average transatlantic liner does in its lifetime.

The Hindenburg’s average crossing time, on ten westward flights to the United States from Germany was under 64 hours; for the eastward trips about 51 hours. The Normandie and the Queen Mary, with runs shorter by hundreds of miles, use about 100 hours. The Hindenburg’s operating expenditure- fuel, gas replenishment, food, crew pay, everything- for each round trip, Germany to the United States, was approximately $80,000. The 1,000 passengers, at $400 a head, made up half of the ten-trip outlay; excess baggage charges, hundreds of pounds of freight and express; and thousands of pounds of mail at 50 cents per half ounce, gave the Zeppelin Company better than an even break for the season, which in transportation is remarkable for a one-unit operation.

So, your eyes fuzzy from staring at weather charts and pressure dials, your head buzzing from the airship versus plane debate, you climb out of the gondola and make your gingerly way along the catwalk back tot eh passenger rooms. You have seen everything about the Hindenburg, except how the passengers take it.

And you might as well be in an old folk’s home late on this second afternoon over the Atlantic, as in the Hindenburg’s

Lounge. The British Captain is pulling the Jap diplomat’s leg, and their laughter seems almost profane in the general drowsiness. “It is like this on every trip” says the Chief Steward; “I keep the windows open, but everybody goes to sleep. The ocean air- it is good enough on steamers, but up here!- you see!”

A shout from some heavy eyed but persistent watcher at the observation panels will fetch all hands on the run. You are north of the steamer tracks and have not spotted a vessel since the first night; but there are other matters of interest. New visions of cloudscape beauty, from this high point of view; and glimpses of ocean life that are impossible from a liner’s deck. There is a pair of sharks; they must be thirty feet below the surface, and you realize how invaluable naval aircraft should be for spotting submarines. And now a huge jewfish. Which at first you mistook for a whale; then another school of porpoises. Sea birds, maneuvering close to the water, catch the lance point of sunlight and glint momentarily like silvered raindrops.

A man from Texas plants himself in front of the foyer clock and growls “What a gyp! You sit around and wait for mealtime, and just when you are starving, and the hands reach twelve, someone comes along and turns them back two hours! We lost four hours yesterday and my stomach is all mixed up!” The food, by the way, is good on board; but neither inspired nor much varied. Weight is the problem, of course; and the Steward’s Department has to figure closely for each trip.

“You must remember,” says Captain Lehmann, “This is the first season; and great improvements will come. The L-130 will be more comfortable; and some changes will be made on the Hindenburg, things we have learned this summer from you good people who have traveled with us. And, do not forget, we dirigible people can also ‘build them larger!’

“The Hindenburg has a gas capacity of a little more than seven million cubic feet, and that is enough to bear up to safe altitudes her dead weight of 430,956 pounds- including fuel, equipment, structure and the like- plus 15,740 pounds- the average weight of 50 passengers and 40 crewmen- plus, again, 26,520 pounds of mail and merchandise. But we know enough at present to build, and have enough experience to operate safely, one twice the size of the Hindenburg!

“The size of future dirigibles will be limited only by the docking facilities available on the shores of the world’s continents. Their speed, too, will increase with engineering progress. We shall make the Hindenburg faster next season, and there will be 18, perhaps more, round trips instead of 10. In the late summer, the L-130 will join her. Perhaps 3000 or more persons will have the opportunity to cross the Atlantic by air in 1937.

Left alone, you gaze down upon a vast bank off Nantucket. It is a graphic illustration of the dangers of marine navigation. You are crossing the steamer lanes; and you can hear the hopelessly blinded ships blowing their sirens in the wilderness below. Up here, the day is still bright. An officer comes by and says you are not going to break the westbound record. You left Frankfurt at 7;30 Monday night, and you will be aground at Lakehurst, New Jersey by nine o’clock this evening, Wednesday. Although it has not been perceptible to you, a strong head wind came up this afternoon and has slowed you down to a mere 50 miles.

Presently, you leave the fog bank behind you, and there, under you, is the Queen Mary, outward bound. She makes an inspiring picture; but her roots are in the past. Up here, you a re helping to begin a new, and greater, era. In 1937, air travel across the Atlantic will be commonplace; with two dirigibles shuttling back and forth, with British and American planes making experimental and mail flights, with Bermuda scheduled by flying boats. You watch the beady lights of the Jersey coast rise like a careless necklace in the west, and you think how inured to wonders our day must be, for we scarcely lift our eyes to achievements that would have brought our grandfathers to their knees, full of praise, as for a miracle.

Sky Cruise : Fellow Travelers

The ‘Sky Cruise” Passenger List: October 5th- October 8/9 1936.

It is possible to identify most of the few passengers described by Mr. Courtney, through the manifest available at Ancestry.com. The Texan disappointed by the daily timetable was 64 year old James Flanagan of Henderson, Texas. The Japanese Diplomat was N. Shibusama, of Tokyo, serving in Berlin. Courtney’s cabin mate was either Alan Charles Seymour Higgins, or Ralph Wilson, both English Officers. Reading between the lines on the manifest, one spots several human interest stories one wishes Mr. Courtney had fleshed out. 20 year old Emma Gager, London hairdresser, embarking on a “New England Honeymoon.” She was unmarried (her father’s last name , given on the manifest, was Gager) and a line has been drawn through the sentence “New England honeymoon.” Was she to be married in the U.S.? Joseph Bonelli and Dora Pils, traveling to the same Philadelphia address, with Dora answering “always” as to the length of her stay~ were they marrying? Eugen Ott, en route to a Diplomatic position in Tokyo, and Ralph Wilson en route to New Zealand~ what might their stories have been, and why did they choose the Hindenburg? Given the lengths of their respective trips, the time saved aboard the Hindenburg did not justify the $400 fare.

Ahrens, Francis. 34. Johannesburg, South Africa. U.S. destination, Plaza Hotel, NYC. Traveling with Stanley Anderson.

Anderson, Joseph. 47. Washington, DC.

Anderson, Stanley. 54. Johannesburg, South Africa. Merchant. U.S. destination, Plaza Hotel, NYC. Traveling with

Francis Ahrens.

Bartz, Werner. 41. Officer. Stettin, Germany. Round-trip.

Berger, Max Bruno. 26. Waldheim, Germany. Merchant. Round trip.

Blaich, Theo. 36. Tiko, Africa. Plantation Farmer. U.S. destination: meeting Mildred Blaich at the Hotel New Yorker,

NYC, NY.

Bonelli, Joseph. 27. 4/9/09. 6153 Vine Street, Philadelphia PA. Traveling with, and may have been engaged to, Dora

Lucia Pils.

Campbell Tyrie, Mrs.Betty. 33. London, England. U.S. destination, Warwick Hotel, NYC, NY.

Campbell Tyrie, James Alexander. 33. London, England. Publisher. U.S. destination, Warwick Hotel, NYC, NY.

Christianson, Carl. 52. Magdeburg, Germany. Director. U.S. destination, Zeppelin Corp. 356 4th Avenue, NYC, NY.

Conn, Harold Webster. 32. Goodyear Employee.

Courtney, William Basil. 42. 2/19/1894

De Grandcourt, Charles. 40. London, England. Producer. U.S. destination, Statler Hotel. Meeting Mrs. de Grandcourt

at Truesdale Lake, South Salem, NY.

De Masso, Joseph. 28. Hartford, CT. A line is drawn through his name on the manifest; he may not have embarked.

Donderer, Hans. 30. NYC.

Eberhardt, Harriet Kimball. 35. 10/7/1901. 46 Walbrooke Road, Scarsdale, NY.

Flanagan, James W. 64. 10/26/1872. Henderson Texas. Waldorf- Astoria Hotel, NYC.

Forester, Lawrence F. 32. Alliance, Ohio. Goodyear Employee.

Froehlich, August. 54. 916 Temberton Road, Detroit Michigan.

Gager, Emma Dorothy. 20. London, England, Hairdresser. US Destination, Statler Hotel, NYC. Notation on manifest

reads “New England Honeymoon.”

Gilmer, Francis Hook. 37. Goodyear Employee.

Griesser, Richard. 68. 5901 Kenmore Avenue. Chicago, Ill.

Grossmann, Edward. 36. 8/2/1900. Chicago Beach Hotel, Chicago Ill.

Haye, Margarete. 31. The Hague, Holland. U.S. destination, Savoy Plaza Hotel, NYC, NY.

Heinrich, Ernst. 50. Selb, Germany. Manufacturing Director. U.S. Destination, 51 West 32nd Street, NYC, NY.

Kayser, Ernst. 37. Berlin, Germany. Journalist. Round trip.

Kelly, Kitty. 32. 4/27/04. Los Angeles, California.

Koehler, Raimund. 57. Leipzig, Germany. U.S. destination, Trade Fair. 10 East 40th Street, NYC, NY.

Meininger, Florian. 61. 1248 Myrtle Avenue, Brooklyn, NY.

Miller, Fannie L. 59. 1/1/1877. F.D. Box 838. Davenport. (Iowa? State not noted on manifest.)

Mueller, Vincenz. 76. 419 Monroe Avenue, Lake Forest, Ill.

Mulligan, Davis. 36. 8/12/00. Washington, DC.

Ott, Eugen. 47. Attache. In transit for Yokohama and Tokyo, via Vancouver, aboard the Empress of Canada.

Pils, Dora Lucia. 25. Stuttgart, Germany. Actress. US Destination listed as home address of passenger Joseph Bonelli.

Her answer to “length of stay” was “always,” which implies that, possibly, they were marrying. A Dora Bonelli, of the

correct age, died in Illinois in December,1993. The same month,a Joseph Bonelli, of the correct age, died in

Pennsyulvania.

Powell, Adolph J. 45. 11/2/1893.

Roehrs, Dr. Wilhelm. 37. Berlin, Germany. Chemical Engineer. U.S. destination, Bakelite Corp., 247 Park Avenue,

NYC, NY.

Schupp, Adam. 67. 1620 Linden Street, Brooklyn, NY.

Schwitzky, Alice. 51. 3/9/1885.

Seymour Higgins, Alan Charles. 37. London, England. Army Officer. U.S. destination, Ritz-Carlton Hotel, NYC, NY.

Shibusama, N. 47. Tokyo, Japan. Diplomat, Berlin Germany.

Soltau, Dr. Karl. 36. Meteorologist. Round Trip.

Stauber, Louis. 22. 6/27/1914.

Teeter, Lorton H. 56. 8/12/1880

Thiemann, Friedrich-Wilhelm. 26. Assistant. Frankfurt, Germany. U.S. destination, F.W. von Meister, 354 4th Avenue

NYC, NY.

Vermehren, Julius. 58. Hamburg, Germany. Merchant. U.S. Destination, Irving rust Co. Wall Street, NYC, NY.

Wahl, Ernst. 38. Berlin, Germany. Engineer. U.S. Destination, Blackhouse Co. Alleghany, Pennsylvania.

Whitney, William Dwight. 37. 8/26/1899

Wilson, Ralph. 28. London, England. Army Officer. In transit to New Zealand, via Los Angeles.

Wilson, W. Lewis. 59. 2/18/1877

Zunino, Frank Jr. 40. 2/15/1896. 655 Park Avenue, NYC, NY.

Zunino. Mrs. Elizabeth. 28. 9/16/1908. 655 Park Avenue, NYC, NY.

(?) Frank. 25. U.S. Citizen. Surname illegible on manifest.

(?) Vincent. U.S. Citizen. Surname illegible on manifest.

Tyler, (?) 47. First name illegible on manifest. Appears to be Reginald.

Hindenburg : Transatlantic Maiden Voyage Passenger List

May 6,- May 9, 1936.

Adams, Clara. 31. 12/3/1884. Stroudsburg, Pennsylvania.

Beckers, William Gerhard. 62. Beckersville, NY.

Berchtold, Joseph. 39. Journalist. Munich, Germany.

Boeckmann, Kurt. 56.

Brooke, Martha Elizabeth. 64. London, England.

Bruer, Karl. 66.

Charteris, Leslie. 28. Author. Weybridge, Surrey, England. Creator of The Saint.

Charteris, Mrs. Pauline. 24. Weybridge, Surrey, England.

Dick, Harold Gustav. 29. 1/19/1907. Goodyear Zeppelin Corp. Akron, Ohio.

Dowdell, Gerard. 30. Southampton, England.

Ernst, Alfred. 52. Hamburg, Germany.

Fickes, Karl L. 34. 2/23/1902. 509 Crosoy Street, Akron Ohio.

Gayk, Franz. 30. Journalist. Berlin, Germany.

Gee, George. 48. London, England.

Goburyn, Andreas Archer. 32.

Graepenburg, Rosie. 37

Graf Schwerin, Detloff. 41. Essen, Germany.

Hay, Mrs. Grace. 40. England.

Hinrichs, Hans. 46. 117 Liberty Street, NYC, NY.

Holden, Edward. 56. London, England.

James, Ralph. 36. Salem, Oregon.

Jordan, Max. 41. Director. New York City. NYC, NY.

Kluthner-Hassler, Rudolph. 32. Director. Leipzig, Germany.

Krebs, Friedrich. 42. Frankfurt, Germany.

Lechner, Louis Paul. 49. 2/22/1887 385 Madison Avenue, NYC, NY.

Leeds, Mrs. Margaret. 48. 9/26/1887. Palm Beach, Florida.

Leeds, Walter Scott. 51. 9/16/1884. Palm Beach, Florida.

McVittie, James. 60. 9/9/1876. Canadian, residing at the Hamilton Club, Chicago, Illinois.

Mertz, Fritz. 29. Dusseldorf, Germany.

Miller, Webb. 45. 2/10/1891. 220 East 42nd Street, NYC, NY.

Parker, Erla. 64. 2005 Wooster Road, (?) New York.

Peck. Scott. 40. 10/24/1895. Air Station, Lakehurst, New Jersey.

Plange, Mrs. Erika. 29. Dusseldorf, Germany.

Plange, Georg. 34. Dusseldorf, Germany.

Ritter, Karl. 52. Berlin, Germany.

Schulte, Paul. 40. Missionary. Aschen, Germany.

Schwab, Erny. 52. Dusseldorf, Germany.

Simon, Frederick Murray. 54. Margate, England.

Strang, Ernest G. 49. 4/23/1887. 400 Rush Street, Chicago, Illinois.

Traupel, Wilhelm. 45. Kassel, Germany.

Turner, Charles. Author. London, England.

Voigt, Arthur. 60. Danzig.

Von Wiegand, Karl. 61. 225 East 45th Street, NYC, NY.

Wagner, Franz. 45. Pianist. Dresden, Germany.

Waltner, Karl. 39. Austria.

Wetzel, Hellmuth. 23. Berlin, Germany.

Wilkens, Hubert. 47. London, England.

Wilkens, Mrs. Suzanne. 35. London, England.

Hindenburg : Final Voyage Passenger List May 6, 1937

Italics indicate fatalities.

Adelt, Mrs. Gertrud. 33. Berlin, Germany.

Adelt, Leonard. 55. Writer. Berlin Germany. Admitted to State Colony Hospital, Pemberton, New Jersey. Discharged

5/16/1937. U.S. Address, c/o Karl Adelt, brother, River Road, Mays Landing, New Jersey.

Anders, Rudolf. Merchant. Loschwitz, Platteleite 5. Dresden, Germany. Body returned aboard the S.S. Hamburg,

5/13/1937.

Belin, Ferdinand Lammot, “Peter.” 24. 1623 28th Street, Washington, DC.

Brinck, Berger. Writer. Stockholm, Sweden. Body returned aboard the S.S. Drottningholm. 5/15/1937.

Clemens, Karl Otto. 27. Photographer. Bonn, Germany. U.S. Address, Mrs. H. Neandross, cousin, 549 Studio Road,

Ridgefield, New Jersey. Sailed S.S. Europa, 5/16/1937.

Doehner, Hermann. Merchant. 31 Alvero Obregon, Mexico City, Mexico.

Doehner, Miss Irene. 14. 31 Alvero Obregon, Mexico City, Mexico.

Doehner, Mrs. Mathilde. 41. 31 Alvero Obregon, Mexico City, Mexico. Born in Pergamino, Argentina.

Admitted to Point Pleasant Hospital, New Jersey. c/.o Mr. N. Ferdhaus, cousin.

Doehner, Walter. 10. 31 Alvero Obregon, Mexico City, Mexico. Born in Mexico City.

Doehner, Werner. 8. 31 Alvero Obregon, Mexico City, Mexico. Born in Darmstadt, Germany.

Dolan, Burtis. 47. 734 Kenesaw Terrace, Chicago, Illinois.

Douglas, Edward. 39. 10/28.1898. c/o brother, Halsey Douglas, 124 Carpenter Street, Belleville, New Jersey. Phone

number Belleville 2-3190.

Erdmann, Fritz. Colonel, Germany Air Ministry. Halle, Germany. Body returned aboard S.S. Hamburg, 5/13/1937.

Ernst, Elsa. 63. Paul Kimball Hospital. Returned to Germany aboard the S.S. Bremen. 5/22/1937.

Ernst, Otto. 77. Died 5/15/1937, at Paul Kimball Hospital, Lakewood New Jersey. Body returned aboard the S.S. Bremen, 5/22/1937.

Feibush, Moritz. 57. 2601 Lincoln Way, San Francisco, California.

Grant, George. 64. Agent. London.

Hinkelbein, Klaus. 36. First Lieutenant. Air Ministry, Berlin. Sailed aboard the S.S. Europa, 5/16/1937.

Hirschfeld, Georg. 35. Bremen, Germany. Admitted to Lenox Hill Hospital, NYC, NY. C/o Adam Scheldtke,

15 William Street, NYC, NY. Sailed aboard the Bremen, 6/29/1937.

Kleemann, Marie. 62. Bad Homburg, Germany. c/o John Bolton, Andover, Massachusetts.

Knoecher, Erich. Manufacturer. Zeulanroda, Germany. Died 5/8/1937, at Fitken Memorial Hospital, Asbury Park, New

Jersey. Body returned aboard the S.S. Hamburg, 5/13/1937.

Leuchtenberg, William. 64. Admitted to Lenox Hill Hospital, NYC. 2 West 86th Street, NYC, NY.

Mangone,Philip. 52. 11/29/1884. Admitted to Paul Kimball Hospital, Lakewood, New Jersey. 245 East 58th Street,

NYC, NY.

Mather, Margaret. 59. 10/11/1878. c/o Mrs. Louise Turner, Prospect Avenue, Princeton, New Jersey.

Morris, Nelson. 46. 38 Dearborn Street, Chicago, Illinois.

O’Laughlin, Herbert James. Admitted to Paul Kimball Hospital, Lakewood, New Jersey. 924 Bonnie Brae, River

Forest, Illinois.

Osbun, Clifford. 39. Admitted to Paul Kimball Hospital, Lakewood, New Jersey. 400 West Madison Street, Chicago,

Illinois.

Pannes, Emma. 56. 11 Woodland Drive, Plandome, New York.

Pannes, John. 60. 11 Woodland Drive, Plandome, New York.

Reichhold, Otto. Merchant. Body returned aboard the S.S. Hamburg, 5/13/1937.

Spah, Joseph. 32. Acrobat. 240-16 Alameda Avenue, Douglaston, Long Island, New York.

Stoeckle, Emil. Deutsch Zeppelin Reederei, Frankfurt Germany. Sailed aboard the S.S. Europa, 5/16/1937.

Vinholt, Hans. 64. Copenhagen, Denmark. Sailed aboard the S.S. Europa, 5/16/1937.

Von Heidenstam, Rolf. 52. Chamberlain. Stockholm, Sweden. Admitted to New York Hospital, NYC, NY.

Witt, Hans Hugo. 34. Major. Admitted to Lenox Hill Hospital, NYC,NY.