The Art and Architecture of the Nieuw Amsterdam

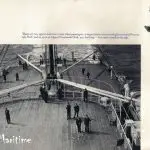

The Nieuw Amsterdam, of all the Depression era ships of state, led a charmed existence. Introduced in recessionary 1938, her pre-war service life consisted of a single brilliant year and can be seen as the final elegant flourish of the golden days day of travel before the war, postwar austerity and jet travel permanently altered the way people traveled. Neither the largest nor the fastest, the Nieuw Amsterdam earned her place in liner history by being the ultimate combination of elegance, comfort, and practical design in a three class ship.

1. Touring The Ship of Tomorrow

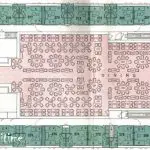

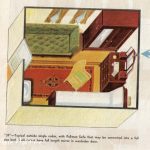

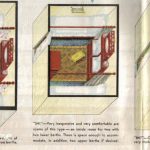

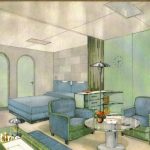

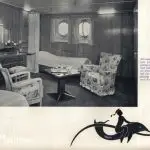

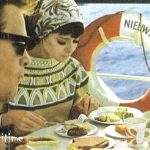

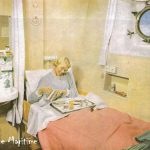

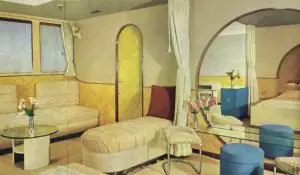

In her original configuration, the Nieuw Amsterdam carried 1220 passengers in three classes, with 566 in First; 455 in Tourist and 209 in Third. She was created with cruising as well as crossing in mind, and so her upper two classes were designed to be as compatible as possible for one-class voyages. First class cabins were paneled in wood, while similarly sized rooms in Tourist were finished with a composite surface, referred to as “Muralart” in press releases. Bathrooms in both classes were of the same size and, again, differed only in finish. All of her First class cabins came with private facilities, as did more than half of those in Tourist; unique to the Nieuw Amsterdam was that a number of Third class cabins on B Deck, meant to be interchangeable with those in Tourist, also had private shower and toilet facilities. ‘Though the Nieuw Amsterdam had nothing aboard to match the Grande Luxe suites of the Normandie, she could boast of uniformly large First class and Tourist class cabins. Her Third class cabins were austere but comfortable, and in addition to the two and four berth configurations, there were also a handful of Third class ‘singles,’ another possible Nieuw Amsterdam first.

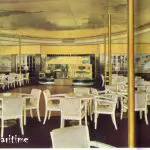

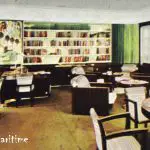

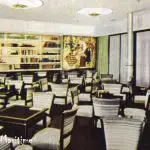

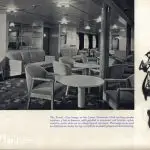

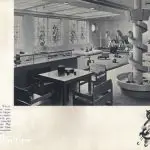

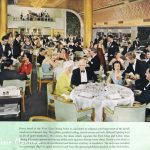

The liner’s public rooms reflected the growing shift towards simplicity of design in the late 1930s. The stark elegance of postwar liners had not yet arrived, but Holland-America’s flagship bore a smoother and , to some eyes at least, less garish interpretation of Art Deco than most of her contemporaries. Color schemes were deliberately muted and, in many cases, monochromatic, with the intent of allowing the passengers to provide the sparkle and color to the rooms.

H.A.L. was justifiably proud of its new flagship and during her single year of pre-war Transatlantic service at least four lavishly illustrated brochures were issued.

The new Holland-America Line flagship, “Nieuw Amsterdam” represents more than the emphasis on historical association that her name implies. She is a modern spiritual counterpart of her city-godparent a vibrant youthful expression from the old country to the youth of the new; bringing the common heritage of each into the vivid spotlight of the present.

The breadth of vision, and the novel treatment of traditional problems of marine architecture complement, in an amazing manner, the vigor, bold enterprise, and confidence that are the dominating characteristics of twentieth century Manhattan. Sixteen architects, judiciously chosen from the younger generation, were entrusted with this task. Working independently with their own staffs of artists, they solved their own problems in their own way. The result is comparable to the finished performance of a massed choir with all its component parts in proper relation to the whole.

Before proceeding to a description of the public rooms, and the more impressive works of art, it may be well to include a reference to an outstanding architectural theme. The motivating idea in many of the rooms was to make them definitely subjective to the passenger, to make their decorations vivacious in his presence. Subdued color schemes and motifs were purposefully introduced for their contributing influence to bright chatter and gay clothes;. The artists, in an inspired moment, resorted to a thoroughly professional solution of the problem. They used the rooms future occupants as their foreground; the room itself as the middle distance, and its decorative appurtenances for background.

A brief history of the ship through 1947.

The Nieuw Amsterdam, 36,667 gross-ton flagship of the Holland-America Line made her initial postwar sailing from Rotterdam and Southampton on October 29, 1947 and arrived at New York, her namesake city, on November 5.

Galleries

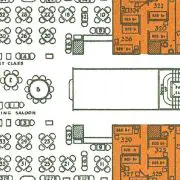

Room Plans

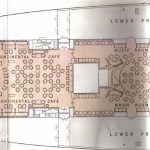

- DP lower promenade aft

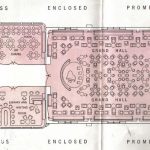

- DP grand hall prewar

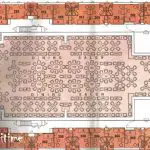

- DP first class dining room prewar

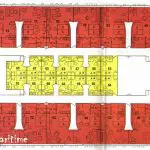

- DP cabins deluxe prewar

- DP cabin Class Dining room prewar

- DP Smoking room prewar

Prewar Gallery

- 000000 halna cabin

- 000000 halna cabins

- 000000 na5

- 000000 na6

- 000000 na10

- 000000 na12

- 000000 na13

- 000000 na21

- 000000 na37

- 000000 na38

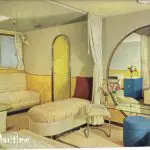

- NA cabin deluxe

- NA Cabin deluxe 3

- NA Cabin deluxe 2

- NA Solarium

- NA smoking room

- NA Ritz Carlton Room

- NA playroom

- NA library

- NA Grand Hall

- NA foyer

- NA dining room

- NA card room

- NA stuyvesant cafe

- NA suite

- NA theater

- NA Third Class Smoking Room TIM

- NA Tourist Class lounge TIM

- nieuw amsterdam 3

- nieuw amsterdam 31

- nieuw amsterdam1

- TIM na 16 tourist lounge

- TIM na 17 tourist library

- TIM na 22 Stuyvesant Cafe Verandah

- TIM na 18 torist smoke room

- TIM na 19 cabin class dining room

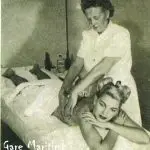

- TIM na masseuse

- Disturbing vignette

Prewar Brochurc

- nieuw amsterdam 21

- nieuw amsterdam 2

- 000000 na36

- 000000 na35

- 000000 na34

- 000000 na33

- 000000 na32

- 000000 na31

- 000000 na30

- 000000 na29

- 000000 na28

- 000000 na27

- 000000 na26

- 000000 na25

- 000000 na24

- 000000 na23

- 000000 na22

Art

- 000000 na4 1

- 000000 na19 1

- 000000 na40

- 000000 na41

- 000000 na52

- 000000 na39

- 000000 na38

- 000000 na36

- 000000 na20

- 000000 na19

- 000000 na18

- 000000 na16

- 000000 na15

- 000000 na14

- 000000 na11

- 000000 na9

- 000000 na8

- 000000 na7

- 000000 na4

- 000000 na3

- 000000 na2

- 000000 na 51

- 000000 na 50

- 000000 na 1

- 000000 45

- 000000 44

- 000000 43

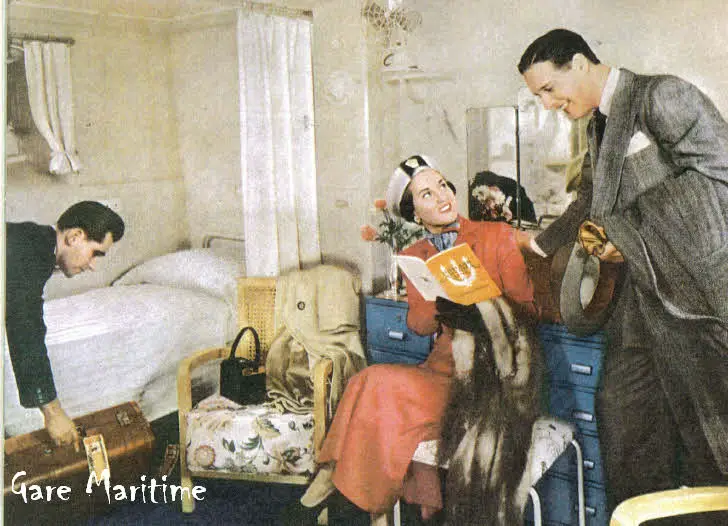

2. Postwar Finery

Courtesy of Tim Yoder

|

To celebrate the return of the Nieuw Amsterdam to transatlantic service, Holland -America issued a particularly lavish brochure, equal to any of her pre-war press material, showing most of her public spaces in color. The extensive shoot utilized dozens of models, clad in stylish day and evening outfits provided by Bonwit Teller, making the booklet not just a great source of photos of the liner but also a nice document demonstrating the high-style of postwar prosperity.

Counting the rivetsThe Nieuw Amsterdam had an overall length of 758 feet, 6 3/8 inches. Her length at the waterline was 725 feet, 11 inches, and her length between perpendiculars 700 feet. Her beam, molded, was 88 feet, and her depth molded to the Cabin Class Sun Deck was 99 feet. Her height, from keel to funnel tops was 147 feet, and keel to masthead 205 feet. The Nieuw Amsterdam’s load draft was 31 feet 6 5/16 inches. Her gross registered tonnage was 36,667 (1947) her displacement tonnage 36, 235 (1947) and her net tonnage 21, 744. She was powered by two sets of Parsons quadruple expansion single reduction geared turbines, which developed 34,000 S.H.P. for propulsion purposes. Her three turbo generators developed 3000k.w. 220 volts direct current. Two sets of Werkspoor Diesel generators developed 950 k.w. 220 volts direct current, available while the ship was in port or in emergency situations. Two emergency Diesel rotors of 50 k.w. each were placed under the after funnel. The boiler installation consisted of six Schelde-Yarrow boilers with a capacity of 30 tons of steam per boiler per hours. Five boilers were sufficient to maintain the pressure necessary to operate the ship. The sixth boiler served as a reserve. The working pressure of the boilers was, at the outset, 550 lbs per square inch, and 743F. A Scotch boiler with a heated surface of 2,800 square feet and a working pressure of 150 lbs per square inch was placed in the same boiler room and used when the ship was in port for heating and galley purposes. All of the boilers burned oil. Each of the turbines had a gearwheel of 14 feet, diameter, weighing 50 tons. The turbines contained approximately 160,300 blades. The blades in the super high pressure, high pressure, and intermediate pressure turbine were made of ATV steel to provide sufficient resistance under the high temperature conditions. The blades of the low pressure turbine were made of manganese copper. Steam of 142 lbs. per square inch led directly from both high pressure turbines to the high pressure feed heater and to the laundry; steam of 85 lbs. square inch was also taken from the high pressure turbine for hotel service and fuel oil heating. Steam of 60 lbs,. per square inch was used for the intermediate pressure feed heater, and steam of 50 lbs. per square inch was led directly from the turbine driven feed pumps to the evaporator. In that way only about 70% of the total steam weight reaches the condenser. Each set of turbines was connected with one main condenser, having approximately 13,300 square feet of cooling surface. The condensers were of the Ware regenerative type and had a mean vacuum of 28.75 inches when the engines were developing the normal shaft horsepower. Salt detectors with electrical alarms were fitted in condensate pressure lines of each condenser. She was a twin screw liner, with triple-bladed manganese bronze air-flow propellers, weighing 22 ½ tons each. At full speed they made 131 revolutions per minute. During the summer of 1967, The Nieuw Amsterdam experienced the first near-catastrophic event of her 29 year career, when a mechanical breakdown forced the cancellation of most of her peak-season crossings. The end might have come there, but boilers were acquired from a U.S. Navy vessel being scrapped in California. They were exported to the Wilton-Fijenoord shipyard in Holland and, after a huge hole was cut in the liner’s side, installed, buying the “old favorite” more time. The Nieuw Amsterdam’s funnels measured 41 feet from base to top and had an extreme diameter of 35 feet and a circumference of about 85 feet. The after funnel contained a complete set of fresh water filters with a capacity of 80 tons per hour, fuel tanks, sanitary tanks and suction ventilators for galley odors. Six Vortex dust collectors were installed in the uptakes with suction fans to eliminate solid particles from combustion gases. Each funnel carried an electrically operated steam whistle. A Jensen Howler foghorn was installed at the liner’s bow which could be heard for 15 miles across the water but was inaudible inside the ship’s public areas. A Grinnell automatic sprinkler and fire alarm system was placed aboard the Holland-America Line’s flagship. 3,600 sprinkler heads throughout the passenger and crew sections of the liner were capable of emitting a jet of water strong enough to reach higher than the ship herself. There were 35 automatic simultaneous alarm bells aboard the Nieuw Amsterdam. She carried 125 hand extinguishers, which were placed at regular intervals. There were 68 fireproof doors above A Deck, and 48 sliding doors on B Deck and below that served as both fireproof and watertight doors. These 48 doors divided the ship into 12 watertight compartments. Her double hull was further divided into 42 watertight compartments, which were used for fresh feed, fuel and lubricating oil. She carried 22 Birmabright aluminum lifeboats with a total capacity of 1,946 persons. Six of these boats were motorized. The davits were Barclay Gravity types, and the lifeboat gear was arranged with the intent of boarding the boats from the Upper Promenade Deck should the need have arisen. The liner also came equipped with 2,452 life preservers. 23 rafts, with a capacity of 506 persons were carried as reserves. The Nieuw Amsterdam, fortunately, never had to put her life saving devices to the test: in her 35 years of service it seems that her most serious accident was a collision with a railway barge in New York Harbor in January 1965. The Nieuw Amsterdam in her 1938 and 1947 configurations, was extensively air conditioned, with both movie theaters, barber shops and all three dining rooms benefiting. The system operated entirely by electricity and was capable of producing cooled air equivalent to an amount given off daily by 300 tons of melted ice. It also dried the air and provided regular circulation in the course of which 25% of it was renewed. The pressure of the air in the conditioned rooms was kept slightly above that of the atmosphere to prevent outside air from flowing in. it was possible to maintain an average of 70F with an outside temperature as low as 10F. All First and Cabin Class staterooms had electric heaters. Two hundred electric heaters in the public rooms supplemented the capacity of the ventilating system. During the 1956-’57 refit, the entire ship was air-conditioned, allowing her to remain competitive with the new breed of liners being introduced. By doing this before lack of central air conditioning became a complete detriment, Holland-America insured that the liner would maintain her reputation for comfort. Many older liners were not as “fortunate” and would not be air conditioned until after it became the norm rather than the exception, fostering negative word of mouth that the pre-War liners remaining in service were “uncomfortable.” The Nieuw Amsterdam had 546 cabins, of which 374 had private bathrooms. There were 1,062 portholes and sidelights aboard, with a total surface area of 17,000 square feet. The public rooms and cabins were fitted out with the following woods: Bird’s Eye Maple; Avodire; Patapsco; Sycamore; Figured Birch; Ash; Burma Mahogany; Chestnut; Silver Sycamore; Aspen; Bird’s Eye Ash; Mountain Ash; Figured Cherry; Rio Rosewood; Laurel; African Cherry; Walnut; Indian Silvergrey; Sapeli Mahogany; Weathered Satinwood; Matore; Macassar Ebony; Silky Oak; Bubinga; Brown Oak; Zebrano. The Nieuw Amsterdam underwent several refits after her 1947 return to the North Atlantic. In 1952, a balcony bar was added to her Grand Hall; in 1956-’57 she was given an extensive internal upgrade during which time her public rooms and cabins were refurbished and her entire interior air-conditioned. It was at this time that the original hull color was changed from black to dove gray. In 1961, the title “Cabin class” was eliminated, with her former Cabin class being renamed Tourist class, and her redundant Tourist class public rooms replaced by a large-multipurpose room, the Henry Hudson Lounge. Her capacity then became 691 First Class/583 Tourist or 301 First class/ 972 Tourist.. Three groupings of dramatic elongated windows, on either side of the ship, were cut into the hull for the new Tourist class room, making it possible to immediately identify a photo of the ship as being pre or post 1961. The liner’s garage was capable of carrying 40 cars. Her total cargo capacity was 252,628 cubic feet. The Nieuw Amsterdam was an exceptionally economical ship to operate, by the standards of 1938 and 1947. Unlike her larger competitors, she had a compact power plant, with only one boiler room, one engine room, and one auxiliary machinery room. Her service speed, of 21.5 knots, was over 2/3 that of the Queen Mary or Normandie and achieved with a total horsepower of 34,000; almost 1/3 those of her rivals. Because of the smaller space allocated for the power and propulsion systems, the Nieuw Amsterdam had a large freight capacity relative to her size: although when the 938 foot, 51,731 ton Bremen passed through the Panama Canal in 1939 she was the longest and largest ship to have done so, the Nieuw Amsterdam in the same year earned the distinction of being the highest taxed ship to pass through-the rate being determined by the liner’s utilized space rather than size. Holland-America incorporated that fact into their advertising. |

- END na 5

- END na 4

- END na 3

- END na 2

- END na 1

- TIM na 5 cabin

- TY NA 3

- TIM na5 de luxe

- TIM na 14 tourist dining room

- TIM na 15 tourist cabin

- TIM na 13A cabin

- TIM na 13 tourist class cocktail bar

- TIM na 12 cabin class theater

- tim na 9 cabin class lounge

- TIM na 10 stuyvesant lounge

- TIM na 11 jungle bar

- TIM na 8 solarium

- TIM na 6 theater

- TIM na 4 elevator

- TIM na 3 smoking room

- TIM na 2 GRAND HALL

- TY NA 9