The Lusitania : Part 10: The Warning

THE WARNING: “Now, if your upper classes run away like this at the first sign of danger, you can’t have any hope for the rest of your people, you know. What would you do in a time of war?”

“What should she have done?”

3000 Accept Risk

Alfred G. Vanderbilt Among Those Who Ignore Written Warnings

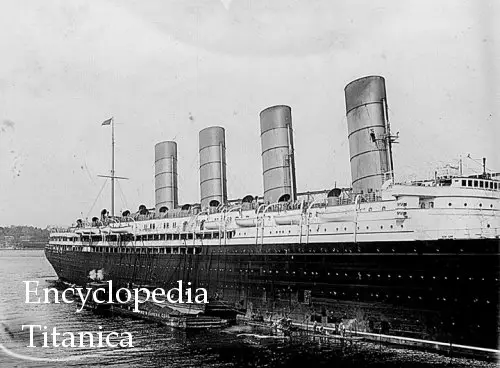

The largest number of transatlantic travelers to leave New York in a single day this spring booked passage on five big liners leaving port today. The Lusitania alone had aboard nearly 900 cabin passengers and a large number in the steerage.

Apparently a notice published in New York papers over the signature of the Imperial German Embassy reminding passengers that vessels flying the flags of the Allies are liable to destruction in the war zone around the British Isles had no effect on the traveling public. There were the usual number of last minute cancellations, but no more than customary, it was said at the various steamship offices. In the absence of authentic figures, it was estimated that more than 3000 persons had reserved sailings.

Besides the Lusitania, other ships sailing were the Danish liner Bergensfjord for Bergen, the Dutch steamer Rotterdam for Rotterdam, and the American liner New York for Liverpool. Seven other liners left for West Indies ports.

When the Lusitania sailed, it had aboard 1,210 passengers. A number of the passengers received telegrams at the pier, signed by names unknown to them and presumed to be fictitious, advising them not to sail as the liner was to be torpedoed by submarines. Among the persons who received such a telegram was Alfred G. Vanderbilt. He destroyed the message without comment.

It is a beautiful fall day, and three of us have taken Barbara to a family style restaurant close to her Connecticut home. Mrs. McDermott sits facing us across the table: the calico-patterned tablecloth; the blond-wood furniture; the sunlight, and Barbara’s brightly colored fall outfit all blend together to convey an almost perfect Rockwell image of Coming Home to Visit Grandmother. Lest this seem too sentimental, the family-style restaurant is, today, literally awash in family style: the booths and tables are over-filled; the line at the restrooms stretches all the way to the New York border, and the cheerful din is all but overpowering. Our waitress is friendly, if slightly harried, and warns us in advance that, due to the overcrowding, the food preparation might be a little slow.

We speak, fondly, of Barbara’s researcher friends who she wishes could be present. We talk, briefly, about her memories of Captain Rostron: “A very handsome man.” Barbara’s early elocution training comes in handy; properly trained, she speaks from her diaphragm and not from her throat. Subsequently, she projects well, and is audible above the ever-mounting sounds of children getting restless as their food does not arrive. “Somebody must have told him I was seasick, but I really have no idea how he found out. My, it is loud in here.” We allow the conversation to ramble. The line at the bathrooms all but grinds to a halt, as one of the two rooms goes out of service. Barbara speaks of her final trip home to England, decades after her marriage. She comments on the fact that the only good thing about the disaster is that it allowed her to make new friends and get out in the world at an age where most people are not as fortunate. “I am starting to get hungry” she comments, as we scan the far reaches of the room for any sign of our meals approaching.

The conversation swings back towards her mother, Emily Anderson. Barbara wonders about how different things would have been, had her mother lived. It is not a “pity me” moment, it is simply an observation she makes. And, she wonders aloud about the infamous German Embassy Warning of May 1, 1915, and her mother: “What should she have done?” The question is not rhetorical; Barbara has been thinking about the warning, lately, and wondering what Emily could, and should, have done.

That is a question that haunted survivors and the families of those who died, for their entire lives. Starting with the song “When the Lusitania Went Down” with its lyrical accusation: “Although they were warned/ the warning was scorned” and carrying through many recent articles and chat room discussions, there has been a sometimes subtle, sometimes not so subtle, hint of chastising and blaming those who found themselves trapped aboard the sinking liner, for ignoring the warning and putting themselves in that position.

It is not simple to answer Barbara’s question. The obvious answer, that Emily should have rebooked onto a neutral ship, is, in fact, not obvious at all. The timing of the German warning was particularly cruel. Had it run one day, two days, a week earlier, there is little doubt that at least some of the Lusitania’s passengers would have thought their situation out and rebooked. But, the warning appeared in the morning edition of the sailing day papers, leaving the passengers no time to make an educated decision. Most, apparently, did not hear of it until they were aboard the ship. Rowland, Emily, and Barbara most likely took an early train from Bridgeport, Connecticut to New York City. There is no way that Emily could have known of the warning until it was too late, unless the Andersons bought a newspaper to read on the cab ride down from Grand Central Station to West 14th Street,.

The same situation played itself out hundreds of times that morning, as out of town passengers left their hotels or arrived at Grand Central and Pennsylvania Stations on the morning trains. What was a person who found out about the warning at the pier or aboard the Lusitania to do? Luggage was already processed into the ship. In many cases, friends and relatives were hundreds of miles away leaving worried passengers with no one with whom to discuss the warning. All but the most experienced travelers would have wondered, “If I get off the ship, will I forfeit my fare?” “How will I rebook on to one of the neutral ships, and is there room?” “How do I get my luggage back? If I can’t get it back, what will I wear for a week aboard the New York, and if I cannot get aboard the New York, how will I get my trunks back from Liverpool?” It was an awful position in which to be.

Emily did not have the advantage of knowing what was to happen on May 7th. If she took Barbara off the ship and returned to Bridgeport, what would she say to her husband? Friends? Her family awaiting her arrival in England? Defeated mother Annie Williams, who was aboard the ship by the generosity of her neighbors; what were her choices on May 1st? If she and her children sailed, and made it to her father’s home in England safely, at least there was some hope. If she did the prudent thing and walked off the ship, with no money, no home, no job, and six children, it was over. Even one day earlier, and Annie and Emily and almost a thousand other adult passengers would have had the luxury of time. Time to make alternate plans. Time to think. The warning arrived, perhaps intentionally, at the precise moment that guaranteed it would foster fear and confusion but be utterly ineffective as a life saver.

The warning was the first of its sort, yet it was simply a restating of something of which the general public had been aware since mid-February. A running theme in newspaper articles covering the Lusitania’s 1915 crossings was the widely held belief that the Germans were out to get the liner. The crossings were tense, and there was a mounting awareness of danger with each subsequent trip. Passengers were not blindsided by the May 1st. warning’s contents, but the symbolism of its appearance on that date and its placement directly beside the Cunard Lusitania ad was lost on nobody.

Quite a few first class male passengers were quoted in sailing day newspapers, and again on May 8th, making light of the warning. The oft-reprinted remarks: “Tommyrot” “Nonsense” “The best joke I’ve heard all day” are used as a blanket indicator of how passengers felt but, in truth, must be taken with a grain of salt. These men, socially prominent, and many with connections to Cunard Line, were mostly taken by surprise by the news. But, unlike the lesser-known travelers in all three classes, they were confronted by members of the press eager for a quote. In an era in which massive premium was placed on both Stiff Upper Lip and personal honor, it was not at all likely that any man would say “It has got me scared- I’m considering getting off before she sails” to a worldwide audience.

Helping to assuage passengers’ apprehensions were the constant, confident, reassurances of Cunard staff members. Surviving passengers later spoke of being told of the ship’s great speed. They recalled assurances that escort vessels would ferry the ship safely through the danger zone. They spoke of discussing the warning among themselves and with the crew, and of how the confidence of those who treated the warning as a joke served to subdue the worries of those who didn’t. One wonders what the result would have been, had the warning come early enough for the United States government to officially comment on it. A running theme through survivor accounts is that, ultimately, few worried about the warning after that first morning and until the liner entered the war zone. Had the warning arrived a few days earlier, and had the U.S. government treated it as a serious matter at that point, it seems likely that, at the very least, those who were apprehensive on the morning of May 1st might have altered their travel plans.

A further factor worth considering when regarding the cavalier attitude of the first class passengers to the danger of submarine warfare, was the large number of them who had completed at least one wartime crossing prior to the May 1st voyage. At least 77 of those about to depart had sailed aboard the Lusitania since September 1914, and of these, at least 64 had crossed since January. They had, collectively, sailed under blackout conditions; sailed on voyages where it was rumored that submarines had ‘tailed’ the ship; sailed on voyages where the ship had idled in the Mersey until the fall of darkness and then dashed to safety with such urgency that the pilot had not been put off but, instead, had been carried to New York. And, it seems that what was impressed upon them was not so much the dangers of a wartime crossing, but the effectiveness of a big liner in eluding attack.

Altogether, at least 196 of the first and second class passengers, one in five, had crossed since the outbreak of war. (See Appendix C.) The confidence and assurance of these people who had experienced wartime travel and emerged unscathed may well have served to settle the nerves of those who were rattled by the warning.

So, in that last hour before sailing a number of factors disastrously intersected. The warning was badly timed. The passengers had neither the information nor the time to make an educated choice. Group psychology and peer pressure certainly played a factor; walking off would have made one appear more hysterical than rational. Misleading statements about speed and escort vessels were made. The U.S. government hadn’t the time to advise citizens on the proper course of action. And, as of May 1, 1915, nothing like the Lusitania had happened yet, leaving Total Maritime War an abstraction to most passengers.

Jim Kalafus Collection

I have started on my travels. The weather is very lovely. I am making for New York, and sail from that port on May 1 by the Lusitania to Liverpool. Don’t think that I have not borne your warning against submarine dangers in mind, but I hear that the Lusitania makes her trip from the Irish coast to port under escort of destroyers, so the risk, if any, will just be sufficient to make things interesting.

I had quite a sorrowful leave-taking from the people at Wilkie- nothing less than a public reception. The pupils of the school lined up and gave me a cheerful send off. I am looking forward to a pleasant trip and then see the auld folks at home….

Letter from James Longmuir Ward, 27, a Lusitania victim, to his father in Shettleston, Scotland.

“She went away in very good spirits” said Miss Wiggins of Dufferin Street when speaking about her sister in law, Mrs. A.V. Wiggins, late of 18 Boon Avenue, Earlscourt, believed to be a victim of the Lusitania disaster. “We teased her many times about the Germans’ warning to sink the Lusitania, but she only said ‘You can’t scare me. They can’t torpedo the Lusitania. She’s too quick.’ “

Mrs. Wiggins’ mother died recently. She has crossed the Atlantic nine times, being aboard the Empress of Britain some time ago when the latter was rammed during a heavy fog. She was 45 years of age, had been in Canada eight years, was married but had no children. Her husband, who is now in the United States, was a partner in the firm Sumner and Wiggins, Painters and Decorators, Spadina Crescent. She has three sisters in England with whom she was to stay while there.

Sarah Helena Wiggins survived, despite the dire forecasts of the newspapers and her family. She died in Southport, Lancashire, on October 11, 1936.

Perhaps the best survivor account in which many of these factors were discussed was a letter written by passenger Michael Byrne, of New York City, on June 8, 1915. Byrne was an excellent observer, and an articulate one as well. His letter sums up, in a single account, all of the sources of anger, frustration and disgust touched on in so many other survivors’ testimonies:

I was a first class passenger, occupying stateroom B-64…

I got on board 8:20 a.m. on May 1st 1915. No officer or any one else questioned me or asked me about my baggage.

On reaching my stateroom accompanied by my wife, a Mr. Kennedy a first cousin of mine, and a Mrs. Waters one of our tenants I immediately looked about the room and found my baggage…On finding my baggage intact, we went to the purser’s office to see if I could insure my baggage, but was told that they did not insure. Next we looked about the lounge and smoking rooms, then went on the promenade deck.

In a few minutes I heard the cry of “All ashore.” So I kissed my wife goodbye; also bade goodbye to my friends and they went down the dock where they lined up to see the boat leave. But when the sailing time came, we were told that the Co. got a message to hold the boat to take on more passengers.

So the time dragged on until 11:30 a.m. when I told my wife that she had better go home as she was liable to take cold. After waving a fond goodbye, I returned to my stateroom and unpacked the necessary clothes and toilet articles for the voyage.

Having completed this, I went on deck and found by my watch that it was twelve noon, and the men on the dock were hauling up the lines on the ship.

So at 12:15 p.m. the Lusitania moved out into the stream and after the tugs had straightened her out we moved downriver under our own power. Then after the pilot left us in the usual way, we steamed ahead for perhaps a half hour, when I noticed we were slowing up.

I focused my marine glasses over the bows of the ship, and saw a warship off our starboard bow, and what looked like a passenger steamer lay off our port bow. On coming closer, I saw it was the Cunard steamer Caronia, now a converted auxiliary cruiser. Then I saw a boat leave the Caronia in charge of an officer who had three gold bands around the cuff of his sleeve. When he came alongside, I could not see whether he handed something to any officer on the Lusitania, or whether any officer on our ship handed him anything or not. However, in a few minutes we were under way again.

I have traveled on mostly all of the large ocean liners, such as the Imperator, Olympic, Mauritania (sic), America (sic), Celtic and numerous others. This being my thirteenth crossing of the Atlantic to English ports, and I know a steamer from stem to stern. I acquired a habit of inspecting every ship I sailed on. So at 7 a.m. on Sunday morning I walked up to the bow and looked over it to see her cut through the water. Then I turned to walk back and while dong so I took particular notice to see if they had any guns mounted or uncounted. There were none either mounted or uncounted, for if there were I would have seen them for I visited that part of the ship every day, once a day or twice, until we were sunk.

Walking aft and on to her stern where I scrutinized everything very closely, but found no guns of any kind or description.

The general conversation on board was in regard to submarines and torpedoes and everyone seemed to think that our great speed would save the ship, and I myself was under the impression that even if we did get torpedoed we would still float.

The weather was hazy, with scattering fog, and we were making between nineteen and twenty one knots until we reached the Irish coast. Then we slowed down to not more than fifteen knots which speed was talked about by groups of passengers. You could hear, whenever you passed a group of passengers: ”Well, why are we not making full speed or twenty five knots?” as Captain Turner told us at our concert on Thursday night that we could run away from any submarine.

It was a little hazy up to twelve noon on Friday, but at that hour the sun shone out clear and the Irish coast came clearly into view with a dead calm sea. All our lifeboats had been swung out over the port side and the starboard side of the ship by the dining and stateroom stewards early that morning.

I went below and entered the dining room soon after 1 p.m., had lunch and was on deck at 1:30 p.m. Lit my cigar and walked around the boat deck, finally stopping under the Captain’s bridge.

On the starboard side, looking out over her bows, at about 2:15 p.m. I saw what I thought was a porpoise, but not seeing the usual jump of the fish I knew it was a submarine. It disappeared and in about two minutes I saw the torpedo coming towards our ship, leaving a streak of white foam in its wake.

Then came that awful explosion, the expansion if which lifted the bows of the ship out of the water. Everything amidships seemed to part and give way up to the superstructure of the boat deck, where I was standing, and our ship seemed to stand still. Our power was cut off, and the captain had no control. Almost immediately after being hit, the ship listed to the starboard at an angle of about thirty degrees, and was settling very fast, or going down by the head.

Most of the first cabin passengers were either in the dining room or between decks. Then came the rush on the boat deck. Most of the people seemed transfixed where they stood.

I stood with my back against the Verandah Café and watched everything that was taking place. The first command I heard was “Keep the boat deck clear” but that was impossible for, by that time, the crew and most of the first class passengers were on it.

Then next I heard the third officer say “It is all right now” and kept repeating it. They tried to put the women and children in the boats, but a great deal of men slipped in also.

The first boat I saw that they were trying to lower, the paying out rope ran so fast that the boat turned over, throwing the people in to the sea. By this time everybody was trying to launch the boats they were in, but succeeded very poorly as the ropes always ran afoul of the davits and tackle. There was no order maintained; there was no one to tell you to get into this boat or that. It was every man for himself.

I adjusted several life jackets on people who did not know how to put them on. There was only a small percentage of them who had jackets on. I buttoned my coat and put on my lifesaving jacket, making sure that all straps were properly fastened.

The first officer passed and I said to him “Are we badly damaged?” and he said they would beach her. I said “How can you do that when your engines are gone dead?”

Then when the water came to the tops of my shoes, I dived off and swam as swiftly as I could in order to get away from the suction. After swimming bout seventy five yards I turned on my back and looked back at the fast disappearing ship.

By this time her bow was just under water, then she seemed to slip quickly forward for about one hundred and fifty feet. Then she shuddered and slipped very slowly down by the head. When the water entered the first smoke stack there was a series of explosions which I heard very plainly. Then the second stack disappeared, and so on ‘til the last stack was under water. After that the stern reared out of the water and she slipped slowly until the sea closed over where the Lusitania was fifteen minutes before.

The suction was very slight. Then came all the wreckage such as spars, deckchairs, galvanized iron ventilators, and everything that was floatable. This wreckage stunned and killed a number.

I swam about, keeping clear of the wreckage. I swam through numbers of dead bodies.

Some of the boats floated around without the occupants using the oars. Others used the oars, but only went round in circles from lack of knowledge as to managing a boat. I swam for one of those and made it. When I put my head over the side, they shouted “This boat is full.” I saw they were much excited, so I just hung on to the lifeline on the side of the boat. After about fifteen minutes I pulled myself up again, and one of the deck stewards who was rowing said “Oh. Mr. Byrne, I am glad to see you.” I said “If you are, then please pull me in.” They pulled me onboard, and I sat down a while. Then I helped at an oar.

Finally, we got the same number of oars going on both sides and we steered for the Irish coast, which was about twelve miles off. After rowing for an hour we saw a fishing smack and we made for her. On reaching her we put the women and children on board first, then applied first aid to those who needed it. The same fishing smack picked up two more boatloads and then headed for shore.

Looking back to where the Lusitania had sunk, I could see about ten small steamers coming at full speed. They picked up all they could find. After another hour, the steamer Flying Fish, a side wheeler, picked us up and headed for Queenstown.

We got no warning of any kind. We saw the submarine come to the surface after the torpedo hit us. Then it submerged again. After the water closed over the ship, I saw the submarine periscope then the manhole, or entrance, at which a man’s head appeared. He seemed to survey the ocean, and the boats, for about two minutes. Then the cover was closed and the submarine disappeared to be seen no more.

From a conversation I had with one of the wireless operators, I know that the Captain knew, and the British Admiralty knew, that the submarines were waiting for our ship. The old proverb says “Forewarned is forearmed.” but absolutely nothing was done to prevent the sinking of our ship. The slightest precautions were not taken. The port-holes were all open. That alone helped the ship to sink rapidly.

When buying my ticket, I was told the Lusitania would make twenty five or twenty eight knots an hour when we would sight the Irish coast. But, she was only steaming fifteen knots when we sighted the Irish coast. The weather was perfect and there was no cause for making only fifteen knots.

Even, for instance, had the captain had an all-hands-on board drill with life preservers when we were two of three days out, the passengers would form on deck and the ship’s officers would inspect us, and anyone who did not know how to adjust his life preserver could have been shown how. A great many people traveling never saw a life saving jacket and do not know how to adjust it. They don’t even know where to find them.

I spoke to quite a number of sailors who told me they were making the first trip of the Lusitania. There was an emergency boat drill every day at eleven o’clock. Oh, it was a pitiable exhibition to look at. When the calliope gave two short blasts there would appear on the starboard side ten sailors- that is the number on each watch- five young boys, two able sea men, and three old men.

There was some motive for having the Lusitania sunk. They knew the submarines were waiting for her. Why did they not use every means at hand to offset it? Because there was a motive, as I said before. And if that motive was sympathy, then either the Cunard Co. or the British Admiralty should be held strictly to account for the lives and property of those who were lost as well as those who were saved.

I refer to the British Admiralty because when I asked the Cunard Co. about compensation for my personal effects, they said file the same claim with the Admiralty and at the termination of war they would collect it for me. In answer, I said “I bought my ticket from the Cunard Co. and not from the Admiralty.” The company knew that the danger was there. What did they do to prevent it? Absolutely nothing.

Michael Gabriel Byrne died in March 1953.

“The worst punishment I could wish for the Kaiser is that he might know for just one hour the dread of being alone when he is eighty. I wouldn’t have him killed, but I would have him put where he never again could have the power to accomplish evil.”

One of the best first hand accounts in which the warning was discussed, was that left by Belle Saunders Naish. Mr. Naish’s attempt to rationalize why the warning should not be taken seriously is, in hindsight, quite sad, and there is something almost poetic about Belle’s writing style: her description of how beautiful the sunlight looked from under the water, and of the moment when she sadly commented to her husband “It cannot be long” are among the most haunting of any remarks made by survivors.

Belle Naish and Theodore Naish

Mrs. Naish, of Kansas City, and her husband, Theodore, were one of the more appealing couples aboard the Lusitania, based on surviving evidence. Belle was about as far from the Victorian “Cult of the Female Invalid” as it was possible for a woman of 1915 to get. Her husband, fifty-five when they married in 1911, and ten years her senior, was a civil engineer of comfortable income, who had done well in real estate and who shared with his wife a love of the outdoors and physical activity. In an era where many women still carried smelling salts, forty-nine year old Mrs. Naish was able to accompany her husband on ten-mile hikes without flagging, and their lifestyle was described as “remarkably wholesome.”

Belle Saunders Naish

Mike Poirier collection

May 1st found the Naishes aboard the Lusitania, booked in Second Class. Friends accompanied them to the ship, and one left with them a copy of a newspaper containing the German Embassy’s warning. Mr. Naish declared to his wife:

We will not worry. No reputable newspaper would accept an advertisement of that Cunard Line size and in it put another in direct opposition. It would be like advertising ‘John Taylor Dry Goods Kansas City Missouri’ and then inserting ‘The Peck Dry Goods Company warns patrons of John Taylor Company as said goods are worthless or stolen.’ If that were official, the notice would have been posted in glaring signs, and each American passenger would have had warning sent and delivered before boarding the vessel.

Mr. Naish fell victim to mal-de-mer despite his robust physical state, and was cabin- bound for much of the voyage. Belle wrote that she spent most of her waking hours tending to her husband and therefore, except at meals, did little mingling on board. He did walk on deck with Mrs. Naish on the morning of May 7th. Both noticed the slow speed at which the Lusitania was traveling, with Theodore Naish commenting “I do not like this; it is too much like calling for trouble.” They both observed a British War vessel, when the fog burned off later in the morning, and assumed that it was an escort sent out to meet the Lusitania: “We had all been told that we were protected all the way by warships, wireless, and that submarine destroyers would escort us in the channel. A lovelier day could not be imagined.”

Mr. Naish returned to his bed, but he and Belle managed to make it to open deck soon after the torpedoing: “We had heard the vessel people telling us ‘She’s alright; she will float for an hour.’ I could see the horizon and told Mr. Naish to look ahead at it and the rail and said ‘It is not true, we are sinking rapidly we are turning very fast. It cannot be long.’ “

The Naishes remained with the Lusitania until the end:

We watched the water, talked to each other; there seemed to be a great rush, a roar and a splintering sound, then the lifeboat or something swung over our heads. I threw up my left hand to ward off a blow and then the water was up to my waist. I thought about how wondrously beautiful the sunlight and water were from below the surface. I put up my right hand, saw the blue sky and found myself clinging to the bumper of lifeboat 22. I finally sat down cold and shivering, but we were all with chattering teeth, and I remembered that deep breaths of cold air suddenly expelled will keep a person warm in very cold weather, so we all tried it to our great comfort. While we sat on overturned no. 22 the men told us to take off our shoes and stockings as we should not then feel the cold so much. I asked the man who first reached out his hand to help me out of the water to write his name on the lining of my shoe, lest in the experience to follow I might forget. He wrote ‘Hertz’. (Douglas Hertz)

Later that evening, it was Belle Naish who observed some small sign of life in the form of architect Theodate Pope as she lay among the dead, on the deck of the trawler Julia. Miss Pope, in her account, stated that it took nearly two hours of artificial respiration to fully restore her. Theodate and Mrs. Naish remained in contact with one another, visiting several times, and Miss Pope, later Mrs. Riddle, demonstrated her life long gratitude by providing for Mrs. Naish in her will.

Belle shared a hotel room, in Queenstown, with Robert Kay, a little boy sick with measles who had seen his heavily pregnant mother swept away as the Lusitania sank beneath them. She praised him for his bravery, for he only cried for his mother once, and was grateful to him for ‘sustaining’ her during the early days of her mourning, Theodore Naish having been lost.

Mrs. Naish left a second account, which corresponds with the first and fills in additional details:

My first thought was “This is the end of earthly happiness.” I saw a great volume of dirty water rise. It was filled with broken iron and splinters of wood, and though it fell all about me not a piece touched me. Then, for what must have been half a minute there was the deepest, most awful silence I ever experienced, the siren did not sound at all, in spite of what the stewardess had told me.

Finally, as realization came, the people began rushing out of their cabin doors. Two women, mother and daughter clasped each other tight in order not to be torn apart. My thought was to get back to the stateroom where my husband lay. But the stairway was blocked with the people coming up from the second cabin. A young woman stood with her arms around the post of the stairway, screaming “Charlie! Charlie!” And I was to hear the same woman still shrieking the same name in acute hysteria in an Irish hotel days later. Both her husband and father were drowned.

After the second cabin passengers had all come up, I started down the stairway and met a rush from the third cabin. They turned me clear around four times before I could get off the stairway and wait for them to pass. My husband met me at the stateroom door with our life preservers in his hand. All three sets of strings on each life belt was tied securely, but we managed to undo them.

Finally, we got them on and hurried up on deck, where we found many people. My husband aided six persons to get into their life preservers properly. One was a woman with a heavy fur coat. “Madam, you must get out of that coat.” said Mr. Naish. “The fur will sink you.” She took it off, and he tied her life preserver on again for her. Another woman was wearing a long, heavy, wool coat with a large fur collar, her life preserver outside of that and her baby tied to the life preserver on her breast. Mr. Naish told her she must take the coat off and manage differently about the baby or both would be drowned. A pitifully strange sight was a woman, glassy-eyed, mouth hanging open and emitting queer sounds. She was dragging her life belt. As we tied it on her, another woman came along, her hat tied on with a long motor veil.

By that time the ship had tipped so far we couldn’t take our footing without taking hold of something. A boat was being launched, and one end dropped letting all the people it contained into the sea. At the sight, I felt faint and asked Mr. Naish to pinch me to help me back to consciousness. He did, and I was alright again in a moment. We made no effort to get into the lifeboats. Mr. Naish had promised me long before he would never force me to get into a lifeboat unless there was room for him.

Now, I saw the water coming closer. A boatman came up and said “She’s steady. She’ll float for an hour.” But I knew she wasn’t steady, and wouldn’t float for an hour. “Look,” I said, “at the horizon and the railing of this boat. We’ll be gone in a minute.” And gone we were. The Irish coast looked far away, and the song “It’s a Long Long Way to Tipperary” kept glancing through my mind.

We took hold of the railing that penned in the lifeboats. I had my arm through my husband’s. But, as I felt the boat sinking I unclasped my hand from his, because I did not want to drag him down. At that moment the ship dipped down and over at the same time, bringing the water up to my armpits. A boat swung out and struck my head and cut it open, and I lifted my arm to keep it from striking my husband in the face. It seemed as if everything in the universe ripped and tore. The deck seemed to strike the soles of my feet hard.

The next thing I knew, I was twenty or thirty feet below the surface of the sea. I thought “Why, this is like being on grandmother’s feather bed.” I was comfortable. I kicked, and rose faster. My head struck something that cut my scalp, and kept bumping. I got my arms around something, and when I came out of the water I was clasping the bumper of an overturned lifeboat.

Mrs. Naish was awarded $12,500.00 for the loss her of husband by the Mixed Claims commission in 1924. A 1932 profile of Belle Naish revealed that the one-time schoolteacher had channeled her grief in a positive direction. She had spent the previous fifteen years working on behalf of libraries for the blind, transcribing books, songs, and tax information into Braille. She mentioned that she still kept in touch with Robert Kay, Theodate Pope, and other survivors who she did not name. She continued to live in the Kansas City area until her death at age 84, on August 25th., 1950. Camp Theodore Naish, a Boy Scout Camp endowed by Mrs. Naish still exists outside of Kansas City.

Robert Kay died in Maspeth, Queens, on November 30, 1981. He was 73.