The Lusitania : Part 12 : Gone Forever: The Dead and the Missing

Eyes picked out by birds…

An elderly lady, between 40 and 50, hair turning grey, eyes picked out by birds, face full round and freckled. Fairly stout, about 5 foot three inches, very well dressed and wearing a lot of jewelry, and had a good set of natural teeth. On the third finger of her left hand she wore four gold rings, one jeweled with white stones, the second jeweled with three blue stones and two white; the third with five pearls, and the fourth jeweled with three red and two white stones. On her left wrist was an expanding gold wristlet watch, with initials A.G.S. on the back, and the watch had stopped at 2:30. On her right hand she wore two gold diamond rings, one set with a large stone and the other with two large and several small diamonds. Also an old gold oval bangle engraved and around her neck was a long gold chain off which something had apparently been broken. She worse several small gold safety pins set with diamonds; a small black bow was attached to one, and she had a gold clip for holding a pair of spectacles…

A second lady, Miss Hickson, was badly mutilated, her eyes being pulled out, probably by birds. She had a bent wrist, but this was the result, apparently, of an old accident….

A fourth lady, also damaged by birds, was well dressed, stout….

Irish Independent

The Lusitania’s death toll was complete upon the death of infant Campbell McKechan, the final “official” victim, on September 15, 1915. He, along with his mother, Elizabeth, brother John, and aunt, Catherine Gill had sailed together for a family visit in Scotland. Only Elizabeth and Campbell returned to their home in Gillespie Illinois, in August 1915, and the infant succumbed three weeks later to after-effects of the disaster. At least 1,198 were gone, and of these, nearly 900 were carried down with the ship or swept away by the currents, never to be found.

…the rigidity relaxed into an inebriate flabbiness, and the features broke down into a preposterously animal-like repulsiveness. I was present as official witness to an autopsy performed on one body seventy-two days dead, but other corpses equaled it in the ravages they displayed. The faces registered every shading of the grotesque and hideous. The lips and noses were eaten away by seabirds, and the eyes gouged out into staring pools of blood. It was almost a relief when the faces became indistinguishable as such. Towards the last the flesh was wholly gone from the grinning skulls, the trunks were bloated and distended with gases, and the limbs were partially eaten away or bitten clean off by sea-creatures so that stumps of raw bone was left projecting.

~U.S. Consul Wesley Frost

One of the saddest aspects of the disaster was the sheer number of people who vanished, leaving only their names and booking information to commemorate that they existed at all. For instance, were it not for a single mention of Millie Baker, and a single letter posted from the ship by Elaine Knight, both of these passengers would have left no record of their lives aboard the ship or of their final moments. Hundreds died unnoticed, and only through obituaries, newspaper profiles, court cases, and sad missing persons queries preserved in the Cunard Archives can portions of their biographies be retrieved.

Sister Isabel Wise, of Kingston, Jamaica, should not have been aboard the Lusitania. Sister Wise, a Deaconess of the Church of England, and founder of St. Patrick’s Anglican Church, in Kingston, had resigned from her duties due to failing health. She arrived in New York City, aboard the Zacapa, on April 23rd, and her immigration papers were marked as In Transit, with no United States address given. However, she spontaneously decided to go ashore, to visit with friends in the city, and changed her booking to the May 1st Lusitania sailing. She explained to her friends that she knew her visit would be the last opportunity they would have to see one another, and that she suspected she would not survive the Atlantic crossing. These suspicions were not attributed to presentiment of disaster, but to depression over her unnamed illness.

Sister Wise boarded the Lusitania, and there her story ends. Her family in Northern Ireland, friends in New York City, and the Anglican Church, made concerted efforts to find anyone who could describe her final hours, but apparently no one came forward. A memorial service was held for her, at St. Patrick’s, in Kingston, on the fourth anniversary of her death.

John and Mary Macky, a couple who had immigrated to New Zealand, were returning home to the United Kingdom for a visit in their old age. He was 60 and Irish, she was 56 and a Scot. They arrived in Vancouver, aboard the Niagara, on April 10, and died together on May 7th, and no one, it seemed, remembered them afterwards. Argentine businessman Carlos Gauthier, 24, vanished leaving a widow, Angeline, in Chicago. Allan and Evelyn Dredge were mis-remembered by survivor Dwight Carlton Harris, who referred to them as Mr. and Mrs. “Grudge” in his letter account of the disaster. The couple had arrived in New Orleans from Belize, British Honduras, on April 26, as passengers aboard the Marowijne, and were returning to England for a visit with their daughter. Harris did not specifically mention seeing them at the final lunch, and they were never seen again.

John and Mary Macky

Amelia Macdona, who had hoped to escort a favorite grandson to school in England, traveled alone and died; no one seems to have spoken of her final seven days aboard the ship. Annie MacHardy, a 31-year-old waitress who worked in Macy’s and earned an average of $18 per week after tips, boarded the ship to visit her daughter in Scotland, and vanished.

Amelia Macdona

Courtesy of Harding Macdona

Carlton Thayer Brodrick, an unmarried 28 year old who earned $10,000.00 per year as chief geologist for a mining corporation operating in Russia, was on his way to Europe where he was to assist Herbert Hoover in the Belgian relief effort. His body was recovered, but he seems to have left no impression on anyone who survived. Evan Jones, 65, of Iowa, was returning to his native Wales to live out his remaining days. He traveled in third class, and his final days and manner of death went unremarked upon by any survivors. His illegitimate daughter in Wales became the lawful heir to his estate. Christopher Garry, of Cleveland, Ohio, was terminally ill with tuberculosis, and was returning to England where he wished to die under his mother’s roof. Elizabeth Horton had spent a year in Cleveland, helping her daughter through pregnancy and her first months of motherhood; she was returning home with baby photos and souvenirs. Mrs. Horton died, and so did Mr. Garry.

Carlton Brodrick

Jane Worden was a 55-year-old dressmaker from Lowell, Massachussetts. Her husband, Charles, 77, was a carpenter who had earned from $1500 to $2000 each year when in his prime. Jane brought in an additional $1000 annually through her own business. She owned the small house in which she and her husband lived, and would have been his sole means of support beyond his savings when he became too old to work any longer.

The Wordens had lived comfortably, and Jane made several trips to her girlhood home in Clonakilty, Ireland. Her 1915 visit would have been brief. She intended to meet her mother, Mary Goodchild, in Clonakilty, and then escort her to a new home in the United States. They held tickets for the Lusitania’s May 14th sailing from Liverpool. Mr. Worden, and Jane’s brother, Geoge Goodchild, asked her to postpone the trip until the fall when, perhaps, the submarine menace would not have been as acute, but she assured them that everything would be alright. Jane Worden boarded the Lusitania alone, and died anonymously.

Thomas and Beatrice Agnew, both 25 and traveling in third class, were returning to Bally Mora, Ireland. Thomas, a carpenter, had spent five years in the Pittsburgh vicinity working and saving money. The Agnews had married in the United States, and the couple was said to have saved “a tidy sum.” They carried all of their possessions with them. A postcard mailed from the ship on May 1st. was the only trace of the couple ever found. Their neighbor in Monessen, Pennsylvania, 30-year-old coal miner Lamond Proudfoot, was returning to Greenhills, Scotland, in second class. He, too, vanished without a trace, although his hometown newspaper in Pennsylvania would later report that he had cabled friends in Pricedale to let them know he had survived. Proudfoot was missing half of his left index finger, an injury shared by none of the unidentified male bodies.

Anne Davis, a 63-year-old widow, vanished without a trace on May 7th. She lived in Benton Harbor, Michigan, with her married second son, Roger, who was a clerk in a steel-casting company. She had no job, but had spent the previous twenty-five years as the primary caretaker of her third son, David Emrys Davis. David, in the terms of the day, was described as “incompetent from birth” or, more gently, “while physically healthy has the mind of a child.” Roger, to his credit, did not institutionalize his brother after Anne’s death. The Mixed Claims Commission granted him $5000 in 1924, $2500 of which was specifically earmarked for the continuing care of David.

Florence “Florrie” Lockwood, president of the New Jersey chapter of the Daughters of St. George, escorted her children, Lillian, 7, and Clifford, 11, and sister, Edith Robshaw, aboard the Lusitania. Beatrice Goodall, a relative of the two women, joined them aboard the ship, along with her two children, Leonard, 7, and Jack, 10 months. The family party was en route to visit relatives in Staincliffe and Dewsbury. No one who survived seems to have commented on the group, and Lillian’s body was the only trace of them ever found. She was buried in one of the mass graves in Queenstown. 32 year old Emily Shaw had grown uneasy over war news, and was returning to England to be with her mother. Charles Waring had recently lost his young wife and was returning to the U.K. in mourning. 50 year old Ella Mae Lawrence was volunteering as a nurse. All completely disappeared.

Florence Armitage, a young widow from London, had arrived in New York aboard the Lusitania in November 1914. She took long-term, lodging at the Hotel Knickerbocker while visiting with friends who lived nearby on West 43rd Street. A postcard mailed from the ship before sailing became the final known link with Florence. She is commemorated on the tombstone of her father, boxer John Burke, in London’s Norwood Cemetery. George Sidwell, of Hamilton, Ontario, seemed to be on his way up in 1915. A church organist and music teacher, he had published over one hundred songs and, finally, seemed to be making progress as a commercial songwriter. Several of his patriotic marches had sold well enough to draw attention to the tunesmith, and he was en route to London in third class, carrying his musical catalogue with him. He was to meet with publishers, one of whom, it was said, had paid him an advance of $2,000.00. Sidwell died leaving no mark on the Lusitania story, no one commented on him later. His wife was left with eleven children between the ages of 23 years old and 10 weeks. Mary Sidwell received a settlement of $8,000.00 for his loss, while his seven minor children were each awarded $1,000.00. Theatrical agent Luigi “Louis” Brilly arrived in NYC aboard the St. Louis on April 11th. He visited Philadelphia, boarded the Lusitania, and disappeared. Diego Olivar, a young clerk from Merida, Mexico, arrived in New York City on the Ward Line’s Monterey on April 25th, and traveled and died aboard the Lusitania without leaving any mark on the story.

James and Kate Barr come close to defining the “average” couple aboard the Lusitania’s fatal voyage. They were of early middle age, educated, active church members, and were returning to their native Kilmarnock, Scotland, for a visit when they died together. Kate was recovered, and buried in Queenstown but, beyond that, nothing is known of their last seven days.

James Barr and Catherine Barr

James was an engineer. Kate was a former teacher, and a church worker. They immigrated to Toronto, where they were popular members of several social organizations for Scots. Their eulogy, delivered in Kilmarnock by Reverend Andrew Aitken, seems a fitting tribute to all of the Lusitania’s “shadow people:”

Mr. James Barr, B.Sc., and his wife were passengers on the Lusitania on her last journey across the Atlantic, and as never a word has been heard from them, or about them, we can only conclude that they went down with the boat. They were children of the Grange Church, and were among its finest spirits. James Barr flung himself into Christian work with an energy and joyousness that infected others; not only did he give his best, but he spurred those around him to do the same. With principals rock-strong, he had a winning personality that endeared him to all. He had gone far in his profession as an engineer and was going farther. He was rapidly making a name for himself in Toronto, and he will be missed there.

Mrs. Barr- or Kate Young, as she was known for many years in our midst- left us not quite two years ago for Canada, left our shores with the good wishes of the whole congregation for a long and happy life. A brighter, happier heart never lived than hers. She threw herself wholeheartedly into the work and life of the church. For many years she was superintendent of the infant Sunday school, and did splendid work. She was the living spirit of health, and a sunnier soul never entered flesh. Her gifts of song and speech were freely used and greatly valued. It is difficult to believe that they are gone from us; the world is a poorer place for us in their absence. Their memory will be green for years to come. They were “lovely and pleasant in their lives and in their death they were not divided.”

Thirty eight year old Elizabeth Seccombe, of Peterborough, New Hampshire, was one of the more admirable women traveling in first class aboard the final voyage.

Miss Seccombe immigrated to the United States in 1897, at age 20. Her father, William S. Seccombe, had moved to Peterborough in 1895, in advance of his wife and children. He became a naturalized U.S. citizen on May 18th, 1898, and through his naturalization his wife and minor children became U.S. citizens as well. Elizabeth, four months past her twenty-first birthday remained a citizen of the United Kingdom.

William Seccombe died in 1910. He was a master mariner, who had served as a Lieutenant Commander in the Spanish-American War. He had also once served as the master of the Cunard Line’s Cephalonia, according to 1915 articles. He left “a small estate and a large family” as one contemporary source put it: Elizabeth had eight siblings.

Miss Seccombe became the mainstay of her family following her father’s death. She was trained as a nurse, and also as a housekeeper and secretary. Miss Seccombe maintained her mother’s home, paid for the education of several of her siblings, and through savings and prudent investment had managed to put aside $7000 of her earnings for herself.

Elizabeth took her brother, Percy, 20, to Europe during the spring of 1914. They returned to Peterborough by way of Boston, aboard the Cunard liner Laconia, on its July 15th crossing.

Miss Seccombe was paying for Percy’s college education. She and he boarded the Lusitania in May 1915, intending to enlist as Red Cross workers in Great Britain. Captain Turner, presumably an acquaintance of the late Captain Seccombe, sent a letter to their mother in New Hampshire assuring her that he would look after them.

Neither survived, but both of their bodies were recovered. Elizabeth, body #164, was buried in one of the common graves in the Old Church burial ground, while Percy was cremated and shipped back to the United States aboard the Lapland.

Hannah Seccombe brought suit against Germany for the loss of her family’s principal breadwinner, Elizabeth. Germany challenged the suit on the grounds that although Mrs. Seccombe was a naturalized American, Elizabeth Seccombe was not. She had lived in the United States for eighteen years, but never applied for citizenship. Germany maintained that the American Mixed Claim Commission was intended to rule on death or injury to U.S. Citizens, and that Elizabeth’s death fell outside of its scope.

This contention was rejected in January, 1925, and Hannah Seccombe was awarded $10,000.00 for her daughter’s loss on February 11th of the same year.

Captain Turner’s letter to Hannah Seccombe has survived, and was recently sold at auction.

A pair of letters document the search for perhaps the most famous couple lost without a trace in the disaster:

From the latest intelligence I can get from the Cunard Office, I fear that Mr. and Mrs. Elbert Hubbard on the Lusitania are not amongst us who were more fortunate, and as a fellow passenger on that boat, and as one who has known Mr. Hubbard for years, may I express to you my deepest sympathy in your sudden and terrible bereavement.

It may be some satisfaction to you to know that Mr. Hubbard and his wife met their end calmly and serenely, together. I am confident of this, for I was standing talking to them by the port rail directly near the bridge, when the torpedo hit the ship on the starboard side. I turned to them and suggested their going to their stateroom on the deck below to get their life belts, but Mr. Hubbard stood by the rail with a half-smile and with one arm affectionately around his wife. She was quietly standing beside him, and no sense of fear was shown by either of them.

I went to my stateroom and got several life belts and came back to the place where I had left them, but did not see them, nor did we meet again on the boat deck.

Therese are poor words of consolation at a time like this, but I trust they will be acceptable to you. I never saw two people face death more calmly or almost happily, for they were speaking together quietly, and each seemed to have a happy smile on his and her face as they looked into each other’s eyes.

Yours very sincerely,

C.E. Lauriat, Jr.

I, William H. Harkness, of 112 St. Domingo Vale, Liverpool, in the employ of the Cunard Company, and Assistant Purser on the Lusitania upon her last voyage from New York, make oath and say as follows:

I knew Mr. and Mrs. Elbert Hubbard, of East Aurora, Erie County, U.S.A., who were saloon passengers on board the Lusitania upon that voyage, and I frequently spoke to both of them. I saw them very shortly before the torpedoing of the ship, but did not see them afterwards. I escaped in one of the lifeboats, and as an official of the Cunard Company, I had to busy myself with the landing of the survivors; but I did not see Mr. or Mrs. Hubbard amongst them, and although the fullest enquiries have been made by me, no information of them since the foundering of the ship has been obtained up to this date, and as there is now no possibility that either of them survives, their names have been registered amongst those lost in the wreck.

William H. Harkness

Asst. Purser, Lusitania

Subscribed and sworn to on May 14th, 1915, before Wesley Frost, U.S. Consul at Queenstown.

An Armthorpe Victim

Young Lady Coming Over to Be Married

Mr. & Mrs. Wilson of Nutwell, Docaster have sustained a very serious and sad bereavement in the loss of their only daughter who is numbered among the Lusitania victims.

The parents are well known in the Armthorpe district. Mr Wilson having been a former gardener at the Rectory.

Their daughter Miss Sarah Wilson, who would have been 23 years of age next month, was coming over to England from New York to be married, which makes her death all the more melancholy. She was engaged to Mr. Chas Bennett, a railway signalman of Bromley, Kent, and the happy event was to have taken place in a month or two.

She was the only daughter of a family of four, and was born at Wragby near Wakefield. She had been in service in London as a children’s nurse, and about a year and eight months ago went out to New York in a similar capacity. She was very popular and well liked by all who knew her.

When her name figured in the lists, her fiance journeyed to Liverpool, but was unable to ascertain any tidings of her. She was traveling as a second class passenger.

The greatest sympathy is felt for Mr. & Mrs. Wilson and family in the sad bereavement.

Alfred Faulkner Wheelhouse was born in Manchester in 1892, the only son of Frederick William Faulkner and Matilda Wheelhouse. He had one sister, and his father had been a marine engineer employed by the Cunard Steam Ship Company. By 1915, his father had died, and young Alfred resided with his mother at 194. Bedford Row, Bootle, Liverpool. His sister was employed at the Post Office in Bridlington at that time.

Alfred followed in his father’s footsteps, also joining the Cunard Steam Ship Company and serving as an apprentice engineer. He engaged as 7th Junior Engineer on the R.M.S. Lusitania on April 12, 1915, at the monthly wage of £10, when the great liner made her final westward passage of the Atlantic Ocean, completing an uneventful voyage from Liverpool to New York. He was also on board when the Lusitania left New York on the afternoon of Saturday, May 1,1915, on what was the liner’s 202nd crossing of the Atlantic. Alfred had served on a number of Cunard’s vessels, including the Lusitania on several occasions, and we can assume that he was familiar with his tasks.

Nothing is known about what specific tasks Alfred Wheelhouse performed during the voyage or how he spent the limited free time he would have had, but when the Lusitaniawas struck by the torpedo shortly after 2pm on May 7th, and sunk within a very short time, Alfred Wheelhouse lost his life. There are no surviving accounts of where he was when the liner was torpedoed, or how he met his untimely death, whether as a result of injuries he might have received, or drowning, but when the pitiful survivors, and the bodies of the unfortunate victims were landed at Queenstown and Kinsale in the late evening of that day, Alfred was not among them, dead or alive.

Word of the disaster quickly spread across the world, and as most of those on board – the crew members -were residing in Liverpool and surrounding areas, it was here that the tragedy was felt most. Fathers, mothers, brothers, sisters, wives, sweethearts, children, relatives, and friends of those on board anxiously sought news of their loved ones. Lists of survivors and identified victims were circulated and posted around Liverpool as details became available, but the only lists where Alfred’s name appeared were on the lists of the missing. Thousands of people gathered wherever and whenever these lists appeared, and one of those who anxiously awaited news was the widow, Matilda Wheelhouse. One can only imagine what emotions this poor woman experienced as she sought news of her only son, Alfred. Did see gather with the crowds reading the various lists? Did she meet the survivors who arrived at Lime Street Railway Station in Liverpool in the days following the sinking, asking those who disembarked from the trains had they any account of her son, or did she remain at home, awaiting word from Cunard company representatives, surviving crew members, or friends, as to the fate of her son, or did she sit waiting and hoping that Alfred would eventually walk into her home?

We can only try to imagine what this poor woman experienced in those difficult days, and we don’t know how long it took her to realise and accept that her son had not survived, but maybe she only accepted that he was dead when word finally reached her that a body had been washed ashore near Ballyduff in County Kerry on July 24,1915, and that property found on this body identified the remains as that of her only son. A telegram was sent by the local police to the Cunard Steamship Company at Queenstown, which stated: –

Body of a man washed ashore at Kilmore. Head, arms, portion of body, feet and one leg missing. No clothes except trousers, black serge, in pockets, gold watch No. 71649 words English make, this case guaranteed to wear 10 years, Lancashire Watch Company Ltd., Prescot, England on dial, double breast gold chain curb pattern around seal suspended in centre, silver match box attached to chain with name A. WHEELHOUSE engraved on it. Sixpence in silver and one cent.”

Following confirmation that the remains were that of Lusitania victim Alfred Wheelhouse, they were given the reference number 258 on the South Coast list of recovered bodies, and it is at this point that we have evidence of the conspiracy to conceal the painful truth from Matilda Wheelhouse, not in any attempt at a cover-up, but rather to spare the poor woman from learning how the sea and the time the body of her son spent drifting in it before being washed ashore, had affected his remains.

Just how long it took news of the recovery of her son’s body to reach her, we do not know, but she was probably notified without any undue delay. Alfred’s remains were laid to rest in an old famine graveyard at Kilmore on the evening of May 24th. – a task no doubt hastened by its condition – and the property recovered from the remains were delivered to Matilda Wheelhouse, at her home in Bootle, on the 28th May. Surely, at this point, she must have fully realized and accepted that her dear son was gone forever.

Matilda Wheelhouse was not content to leave matters rest at just being notified of the recovery of her son’s remains, and enquired of the Cunard Steam Ship Company as to the details of her son’s burial. The company wrote to Sergt. William Best, who was the Sergeant-in-charge of the Royal Irish Constabulary Barracks at Ballyduff, and who would have been responsible for dealing with Alfred’s body when it had been discovered washed ashore, seeking specific details. Sergt. Best replied:

R.I.C.

Ballyduff. Co. Kerry.

27th July 1915.

Cunard Company Queenstown

Gentlemen

I beg to acknowledge the receipt of your letter of 26th inst; and to state that the body of Mr. Wheelhouse was buried on evening of 24th inst; in Kilmore Graveyard, which is on the seacoast, and adjacent to where the body was washed ashore. The burial was well carried out and a number of persons followed the remains to the graveyard, and remained until buried, and great sympathy was exhibited by those present, some of the women shed tears over the coffin.

The body was buried in a new grave in the corner next the sea. The graveyard is a neat one mostly all sand, and is about 2 miles from Ballyduff, and if anyone of the victim’s friends visits this place, I shall point them out the grave where the body lies.

I am Gentlemen

Your obedient servant

Wm. Best, Sergt.

Whether or not the burial took place as described by Sergt. Best is unknown for certain, but in those days it is safe to assume that a badly decomposed body recovered from the sea would have been interred as soon as possible for health reasons. Whether or not anyone other than the burial party attended the funeral, or whether or not women cried over the remains, is a matter of some doubt, but is obviously something which may have given some comfort to Matilda Wheelhouse.

Despite all this, Matilda Wheelhouse was not going to accept what she was being told at face value, and expressed her desire to visit her son’s final resting place. The Cunard Steam Ship Company wrote to Sergt. Best again, on the 31st July, stating:

Dear Sir,

Our Queenstown Office have forwarded to us your letter of 27th inst., relative to the burial of Mr. Wheelhouse, a “LUSITANIA” victim, at Kilmore Churchyard. We are obliged to you for the information contained therein.

Mrs. Wheelhouse, the deceased’s mother, intends leaving Liverpool on Tuesday for Kilmore in order to visit the grave. We have instructed her as to the best means of proceeding there, adding that if she calls upon you you will conduct her to the grave. We trust that you will be able to do this and extend to Mrs. Wheelhouse all the assistance that you possibly can.

We might inform you privately that we did not tell Mrs. Wheelhouse the exact condition in which the body was recovered. We thought it best for her to remember her son as he was in life and not to tell her what state it was in. We are sure you will use every discretion when she, as no doubt she will, enquire of you the condition in which the body was found.

With many thanks for the assistance you have given us in this matter.

Yours faithfully,

The Cunard Steam Ship Company, Ltd.

From this letter we can clearly see that officials at Cunard were very sensitive in their dealings with Mrs. Wheelhouse, and their reasons for keeping certain information from the poor woman is clearly stated.

Following on from this, the Cunard Steam Ship Company made very detailed and comprehensive arrangements to allow Mrs. Wheelhouse visit Alfred’s grave, and ensure that she got every courtesy and consideration on her journey. This letter, sent to Mrs. Wheelhouse on the day of her journey, details her travel itinerary, and advises her as to the arrangements made by them, on her behalf:

CUNARD LINE

General Manager’s Office.

LIVERPOOL

August 3rd. 1915

Mrs. Wheelhouse,

194. Bedford Road,

BOOTLE

Dear Madame,

We enclose herewith a first class railway order made on the London and North Western railway Company to Lixnaw. On presenting this at the Booking Office at Lime Street Station they will supply you with the necessary ticket.

We have made enquiries at the Station as to the best means for you to travel to Lixnaw. We are afraid that it will be necessary for you to break your journey on route.

If you proceed by the 8-40 train in the evening from Lime Street, via Holyhead you will get into Dublin (North Wall) at 7.30, a.m. You will then have to go to Kingsbridge Station, Dublin, where you will get a train for Limerick at 9-15 a.m., arriving Limerick at 2.50. You leave Limerick at 2.5., arriving Lixnaw 4.57. We do not know the extent of the journey from Lixnaw to Kilmore, but it is quite evident that you will not be able to return from Lixnaw the same evening. Being a little quite village it is also quite possible that you would find much difficulty in obtaining accommodation for the night.

On the other hand if you care to travel by the train leaving Lime Street at 11-10 a.m., you would arrive at Dublin at 5-30 p.m. You would have to proceed to Kingsbridge Station where you would get the train for Limerick, leaving at 6-15 p.m. arriving Limerick 10-25 p.m. If you broke your journey at Limerick we are quite sure that you would be able to obtain the necessary accommodation. You could then leave Limerick by either the 6.15 or 10.30. These trains would land you at Lixnaw at 9.38 and 1.2 respectively.

Of course it is for you to decide by which train you will travel.

As to proceeding to Kilmore we have arranged with the railway Authorities to provide you with a conveyance. This conveyance will also bring you back to Kilmore. There will be no charges for you to pay in this respect. All you will have to do will be to see the Stationmaster at Lixnaw, and hand him the enclosed note from the L. and N.W. railway. The General Manager of Great Southern and Western Railway Co., has been requested to instruct the Stationmaster at Lixnaw to provide this conveyance for you, so that you will have no trouble in this direction.

We trust that the particulars herein contained will assist you in safely arriving at Lixnaw and later on at Kilmore and that you will be satisfied with the arrangements which were carried out in respect of the burial of your son.

You will of course remember to call upon Sergt Best of Ballyduff, who will direct you to the grave. We wrote to him on Saturday, stating that you would arrive this week, and we requested him to give you every assistance.

Yours faithfully,

The Cunard Steam Ship Company Limited.

However Matilda Wheelhouse decided to travel to see the grave of Alfred is not recorded, but there is no doubt that she completed the journey. Following her visit, Sergt. Best wrote to the Cunard Company notifying them of the fact. Where as his letter does not survive, the reply sent to him from the company does:

8th August 1915

Sergeant Wm. Best, R.I. Constabulary,

Ballyduff, Co. Kerry.

Dear Sir,

We are in receipt of your communication of 6th. Instant, containing an account of the arrival of Mrs. Wheelhouse, and the assistance you so kindly gave her. We appreciate very highly all that you have done in this matter, especially the fact that you refrained from letting Mrs. Wheelhouse learn the exact condition in which the body of her son was recovered. As we stated in our previous letter, it is much better for her to remember her son as he was in natural life, and not to have any idea of the way his body had been mutilated.

We enclose herewith Postal Order for £1.1.0 which we desire you to accept from us as a slight recompense for the services rendered, and expenses incurred by you in this matter.

Again thanking you for all you have done.

Yours faithfully,

The Cunard Steam Ship Company, Ltd.

Thus, the deception appeared to have worked, or maybe Mrs. Wheelhouse suspected all along that the details provided to her were not complete, and played along, either for her own peace of mind or out of politeness for all those who went to such great lengths on her behalf. Whatever she knew or believed, she wrote a letter to the Cunard Steam Ship Company on her return:

194. Bedford Rd

Bootle, Liverpool.

August 9th 1915.

Dear Sir or Sirs,

I have returned from my long journey. I have found the guide you so kindly sent me excellent. I do not know what I should have done without it.

Your very kind arrangements for my comfort in traveling was far more than I could of expected and I cannot thank you enough.

I met with much kindness on my journey.

Sergeant Best was very kind, if it had not been for him I never could have found the grave – as it is a wild place.

I naturally was looking for a Church but there is no Church anywhere near, it is just a piece of ground walled off. At the time I felt disappointed. Anyone always living in England would do, but the people think it quite nice. But I have never seen a place like it before for a Church yard. The Sergeant said I could have some wooden railings put round. He is seeing about it for me so that we should know the place where he is laid. I know well that it only the body there but I am very glad I have been and I have thought it well over. There are many that do not know where their dear ones are laid, but I know I can think of the place where my dear Boy’s body is laid. I am sorry I cannot ever repay you for your kindness to me, but I sincerely thank you with all my heart.

I am sorry to have intruded so much on your time, I could have told you better.

Believe me to remain,

Yours respectfully,

Mrs. Matilda Wheelhouse.

P.S. I hope I have expressed myself fully in this letter, I have tried to. M.W.

The Cunard Steam Ship Company wrote back to her, acknowledging her kind remarks, and presumably Matilda Wheelhouse lived out the rest of her days mourning her loss but taking some comfort in having visited his grave. Alfred Faulkner Wheelhouse rests peacefully in the corner of Kilmore Cemetery, where he was buried in the grave beside the wall nearest the Atlantic Ocean, which graciously gave him up and allowed his poor widowed mother some comfort. The cemetery is almost a perfect square with stone walls marking the boundary, built in the traditional coastal way. Local history tells us that the cemetery was originally used during the Irish Famine, and occasionally to bury bodies of seafarers washed up along the nearby coast. No headstones exist, save for one against the back wall of the cemetery over a clearly marked grave. My enquiries revealed that a young girl from Tralee was originally interred there, but her family later had her disinterred, and buried in Tralee. Other than that, small stones rising up from the ground mark the resting places of long-forgotten famine victims and mariners.

As for Alfred Wheelhouse’s grave, the only clue we have to its location is from Sergt. Best’s account. If the wooden railings were ever erected around the grave, no sign of them exist today, 92 years of Irish weather having eradicated any trace of them. If Matilda Wheelhouse ever caused a headstone to be erected, that too has disappeared.

Presumably, if Alfred’s sister married, then the family name disappeared, and it is not known if any relatives of Alfred Faulkner Wheelhouse survive today. Did his mother or sister ever return to visit his grave again, or am I the only person who has visited his grave in generations?

Alfred Wheelhouse’s name is recorded on the Mercantile Marine Memorial at Tower Hill in London. This memorial was originally erected to commemorate all those who lost their lives during both World Wars while serving with the Mercantile Marine, and who have no known graves. The Commonwealth War Graves Commission was not aware of Alfred’s resting place when erecting the memorial and inscribing his name, but in recent years they have updated their Tower Hill Register to reflect the location of his grave.

He was also commemorated on a brass plaque erected by The Liverpool Branch of the Marine Engineers’ Association in the Britannia Rooms of the Cunard Building in Liverpool. Underneath the badge of the association was engraved:

Roll of Honour

LIVERPOOL BRANCH

A TRIBUTE TO THE MEMORY OF THE MEMBERS, WHO LOST THEIR LIVES THROUGH ENEMY ACTION IN THE

GREAT WAR. 1914 – 1919

and then followed the names of the 226 former members, including Alfred Wheelhouse. This plaque is no longer in the building and its current whereabouts is unknown, if it still survives.

If any readers find themselves in the vicinity of Ballyduff in County Kerry, and can spare the time, enquire locally as to the location of Kilmore Cemetery, and spend a few minutes to pay tribute to a young man whose remains were given up by the sea and rests today, anonymously, in a very scenic part of our island, at peace.

The letters re-printed above are to be found in the Special Collections and Archives Department of the Sydney Jones Library in the University of Liverpool and are used by the author with the necessary permission.

-Peter Kelly.

Mrs. Rose Bird: About 5’ 5” tall; very thin; sallow complexion; black eyes and dark brown hair.

Wearing earrings- either Brilliants, or droppers of some dark stone. Probably wearing a dress of dark blue serge with collars and cuffs of Scotch plaid, and waist of silk with embroidered small flowers.

On last two trips across was very weak and always took her meals in her cabin. Miss Morrow, the stewardess, could identify her if latter has survived. Shoes (low) of grey leather at ankles. A broad wedding ring and probably two others; one opal ring.

Young Wife Gone

Donald Barrow, Monmouth, was returning from Canada with his wife, who was a Canadian girl only twenty years old and married only ten months ago. This morning, Barrow’s mother received a telegram from Queenstown saying “I am safe, but May is gone.” May was the name of his young wife. Barrow was returning to England to join the army.

Mrs. Jane Travers, another local Northampton victim, went to the States sometime ago, and married a German American two years ago. He had been out of work recently and his wife’s parents, Mr. & Mrs. Turner, sent recently an advance of £10.00 to meet the cost of her passage home. In the light of events, it is additionally cruel that the stricken parents should have made so great a monetary sacrifice with such a terrible result.

Jane Travers, 30, lived in Newark New Jersey. Whether she was deserting her husband or simply returning to her parents until his financial situation improved has not been determined.

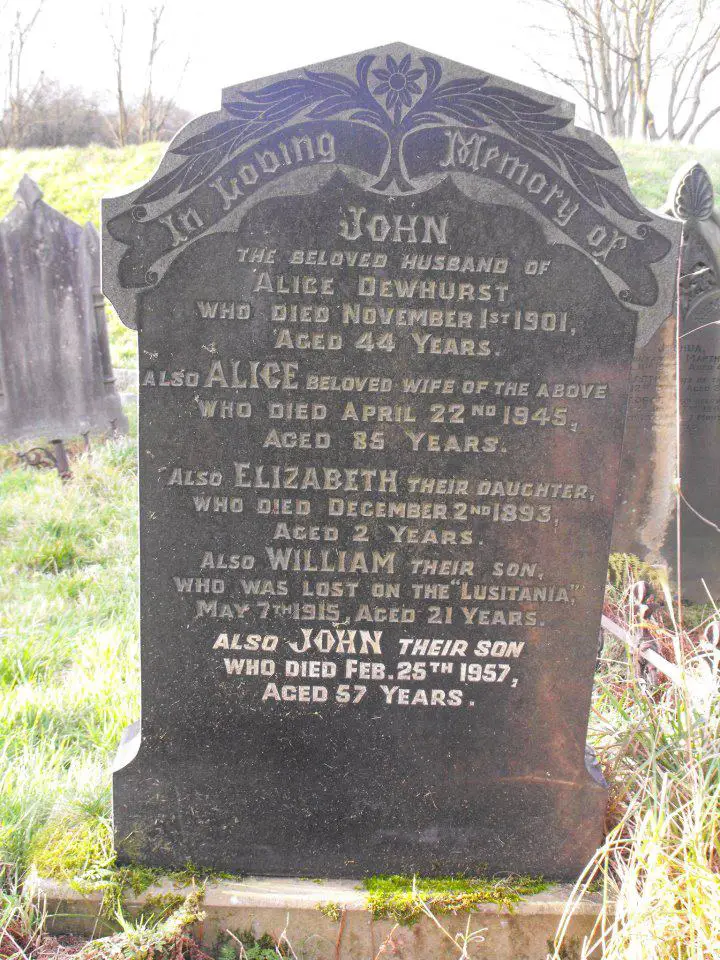

Memorial to Lusitania victim William Dewhurst

Courtesy of Ryan McKeefery

Two bodies…

Two bodies were recovered off the coast of Barry, South Wales, on May 12, 1915, by the steamship Kylesford, from Glasgow, and landed at Barry Docks on the 13th. Captain Duncan Graham stated that both bodies were found floating in the Irish Sea and that the body of the female, referred to as Body #1, was found floating face up wearing a lifebelt. The other body, a male, was presumed to be a steward. The woman’s remains were described as follows:

Female aged 40-50 years old, hair dyed black, 5’6 ¾” inches tall, wearing a navy blue skirt and coat with letters “CW” worked into the clothing. False teeth set in gold, and her American boots which had suede tops, written inside were the makers name F.E. Foster & Co- Chicago on the inside. Property: Gold stamped bangle with 17 diamonds, 1 American split ring, Pearl necklace with pearl screw earrings, 4 diamond rings on middle left finger and 1 platinum ring with 2 large diamonds.

An inquest was held on May 14th. by Coroner David Rees who stated that he had received a telegram, according to which, the body was assumed to be that of Mrs. Catherine Willey, based on the C.W. initials in her clothing. Her property was handed over to the American Consul in Cardiff after the body was formally identified, and was forwarded on to the family. The body was embalmed on the coroner’s instructions, by Messrs Vivian of Cardiff, and shipped back to the United States aboard the SS Lapland on May 19th. The costs incurred in shipping were $810.00. A private family burial took place at Rosehill Cemetery, Lake Forrest, Illinois.

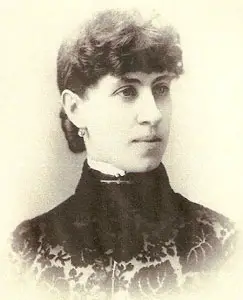

Catherine Willey

Courtesy of Corsone Ellis

Mrs. Willey was born Catherine Dietrick in Jackson, Illinois on August 23, 1862. Her father was a doctor father in a large asylum for the mentally ill. The Dietrick family was prosperous and Catherine was given every opportunity for advancement. She graduated from Illinois College and went on to study at the local College of Music, in Jackson. She performed at numerous concerts and parties, and became regionally very well known. Catherine married Robert Bruce Sterrit, on August 1st., 1877, and moved to his home in Pennsylvania. The couple’s only child, Katherine Bruce Sterrit, was born thirteen months later. Catherine had returned to Jackson for the birth, and it appears that she never returned to her husband. The couple divorced a few years later.

Catherine married Cameron Willey, but that marriage ended in divorce as well, in 1903. Her divorce settlement amounted to $7,200 per annum, which allowed her to live very comfortably. Mrs. Willey subsequently made her home in Paris, France, but made regular visits to her family in the United States.

Catherine WIlley, left: in her early 20s, right: just after her wedding to Cameron Willey c.1900

Courtesy of Corsone Ellis

Catherine Willey decided to return to Paris in April 1915, after spending several weeks with her daughter Katherine and son- in- law Robert Thorne, in Lake Forrest, Illinois. She left Chicago on April 28th, and spent two days in New York before boarding the Lusitania. She visited with friends in New Jersey, and told them that she was thinking of converting a large home she owned outside of London (Paris?) to a residence for penniless war widows. She was allocated cabin B36 on the Promenade deck. Catherine Willey’s activities while onboard are not recorded.

Rumors that Mrs. Willey was returning to France to work for the Red Cross were disproved, after her passport application and other documentation showed that she was making large financial contributions only. She was returning to manage her properties in Paris.

Compensation was awarded to Catherine Willey’s only child, Mrs. Katherine Thorne, on January 14th 1925 in the amount of $15.000.00 for loss of life and $6,910.00 for loss of property.

Among the small company of artisans who arrived at Catheart from America a few weeks ago to work in the engineering shops of Messrs G. & J. Weir was Mr. Edward Dingley, an Englishman who for the past twenty-two years resided near New York.

When he came to Scotland, Mr. Dingley left behind him at Long Island his young wife who, for a considerable time past had not been in the best of health. In the belief that a stay in Britain, which Mrs. Dingley had left while quite a child, might hasten a complete recovery, the husband wrote his wife and suggested that she might join him. The lady was agreeable, and in due course it became known that she had booked to sail on board the Cameronia.

While seated at tea at his apartments on Friday evening a friend, who had been glancing over his newspaper, remarked to him “Go down on your knees Mr. Dingley, and thank God that your wife did not sail aboard the Lusitania.”

The tragic fate of the liner startled Mr. Dingley. He dismissed the fears which began to rise within, but they returned with increasing insistence. In the end he decided to send a cable to Long Island with a view to establishing the facts. To his horror the reply came next morning: Mrs. Dingley sailed with the Lusitania. The explanation is simple. The Cameronia’s passengers at the last moment were transferred to the Cunarder.

On learning beyond dispute that his wife was one of those who traveled by the Lusitania, Mr. Dingley proceeded to Queenstown for the purpose of acquiring knowledge first hand. Last evening a telegram reached his friends in Glasgow from the south of Ireland. Its terms extinguished all hope. The message read: Burying my wife today, Queenstown.

38 year old Catherine Dingley was buried in private grave #591.

FATAL AUTO ACCIDENT

While crossing Broadway, between Broadway Place and Walnut Street shortly before six o’clock last evening, Mrs. H.G. Bullen, wife of H.G. Bullen of the Canadian Bank of commerce, and residing at suite 20, Muskoka Apartments, 110 Young Street was struck by an automobile being operated by Mrs. T. Julius, wife of Mr. Julius of Julius Bros Café proprietors, and fatally injured. She was taken to the general hospital, where it was found that she had three broken ribs and severe internal injuries. She was unable to speak, and consequently the police for a short time were at a loss to determine her identity.

At the time of the accident the automobile was traveling west on Broadway at what is described by witnesses as a moderate rate of speed. Perceiving the woman crossing the street, Mrs. Julius sounded the horn on the car. Mrs. Bullen, however appeared to spectators as confused and unable to get out of the way of the oncoming car. The car struck her and dashed her to the pavement, the wheels passing over her body.

Mrs. Bullen was a lady of about 24 years of age, and had resided at the Muskoka apartments for a short time. Her husband was notified of the accident, but arrived at her bedside too late. She died at about 7:30 p.m.

~April 16, 1915, Manitoba Free Press, Winnepeg.

Henry Garnet Bullen, ledger keeper at the Canadian Bank of Commerce in Winnipeg, was returning to his home in Cork, Ireland, to visit relatives and recover from the loss of his wife. Mr. Bullen had been in Canada for five years in 1915, and was newly married. He took a leave of absence from the bank, for he planned on returning to Canada. Mr. Bullen traveled in third class, and was lost without a trace. No one later recalled meeting him on the voyage, or encountering him during the disaster.

£25.00 Reward

Upon identification being established, a reward of £25.00 will be paid to any fisherman who finds the body of Miss C. Dougal, a saloon passenger on the SS Lusitania, and brings such body to the police at Queenstown.

Particulars: Tall, about 5 feet 10 inches. Aged 23 years. Thin body, sallow skin, loosely built, long legs, long shaped hands, very large dark eyes, long lashes, well curved eyebrows, very dark brown hair, thick, and usually waved, and parted in the centre, hollow neck. Long thin face. Probably wearing very nice and named underclothing, and may have on jewelry. Usually wore Sorosis boots. Special JEWELLERY: A set of Pink South African stones set in gold: Gold broach formed of a miniature miner’s tools, pick, shovel, and pail, and a small piece of gold. Other jewelry, pendant, broaches and pearls.

Catherine Dougall left her home in Guelph, Ontario to travel to her birthplace in England. She intended on visiting relatives. Her cabin was A15, on the boat deck, and her cabin steward was Edward Bond. The reward went unclaimed: her body was never identified.

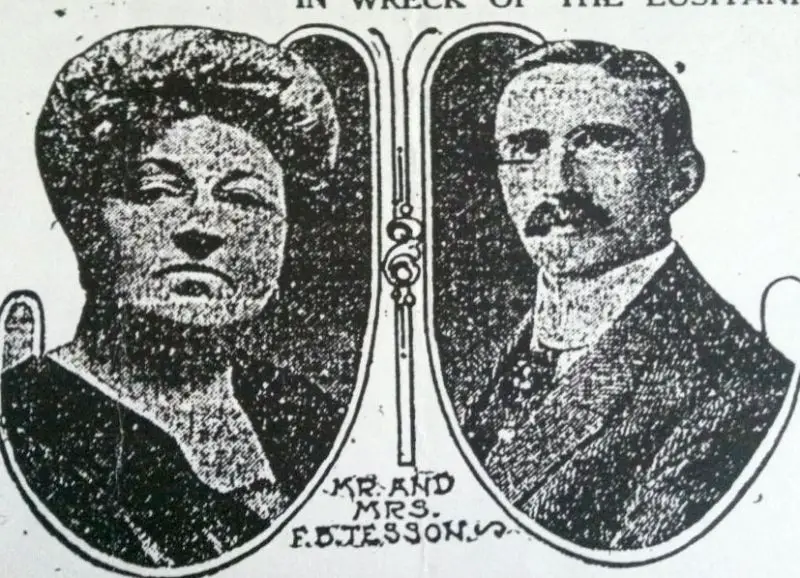

Frank B. Tesson and his wife, Alice, died together aboard the Lusitania. Tesson was the head shoe buyer and Vice President for the Board of Trade at Wanamakers department store, in New York City. He was also a representative of the Excelsior Shoe Company, and was traveling abroad to conclude a business deal involving the sale of 3,000,000 pairs of war boots to the Russian Government. The couple was allocated Cabin D10 for their journey. Eugene Posen, a fellow Wanamaker employee accompanied them. It appears that the Tessons and Posen spent a great deal of time together during the voyage. Posen survived; the Tessons did not, and their bodies were never identified, if recovered. Wanamakers published an obituary dedicated to Frank Tesson in The New York Times on May 15, eight days after the disaster. Grief stricken at the loss of her son, Emily Duncan Tesson had a memorial headstone erected in Alton Cemetery for Frank and Alice.

(Courtesy Paul Latimer)

The Tesson estate’s case against Germany, made before the Mixed Claims Commission in Washington DC, contains many interesting details of the lost couple’s lives and is typical of the mixture of legitimate and questionable claims upon which the commission had to rule:

United States of America on behalf of S. Stanwood Menken, Admisitrator of the Estate of Alice E Tesson, Deceased, and William Atkins, Charles Atkins, and Roy Atkins, Claimants, v Germany Docket Nos. 217 and 293 United States of America on behalf of Andrew C. McGowan, Admistrator of the Estate of Frank B Tesson, Deceased, and Emily Duncan Tesson, Bertha Angeline Montgomery, Lillian Josephine MaKinney, and John Williamson Tesson, Claimants, v. Germany Docket No. 544 Parker, Umpire, rendered the decision of the Commission.

These two cases, which have been considered together, are before the Umpire for decision on a certificate of the two National Commissioners certifying their disagreement. A brief statement of the facts as disclosed by the records follows: Docket No. 293 duplicates the claim made in Docket No. 217.

Frank B Tesson, then 29 years of age, married Mrs. Alice Atkins, then 40 years of age, in August 1895. There was no issue of this marriage, but Mrs. Tesson had three children by her former marriage- William, Charles, and Roy Atkins, then 21, 18, and 8 years of age respectively, all American nationals since birth. Roy Atkins was born and has ever remained a cripple, is unable to walk without the aid of a cane and then only with great difficulty, has no use of his left arm, is unable to perform any manual labor or do anything toward earning a livelihood.

During most of the time between 1895 and 1914 this crippled son lived with and was cared for by Mrs. Tesson and her husband in St. Louis, Pittsburgh, Philadelphia, and New York successively. During the years 1914 and 1915 and for short periods of previous years, when not residing with Mr. and Mrs. Tesson paying his board and furnishing him with money sufficient to provide wearing apparel and other necessaries of life.

Both Mr. and Mrs. Tesson, American nationals, then 49 and 60 years of age respectively, were passengers on and went down with the Lusitania. They died intestate. At the time of his death Tesson was assistant manager of the show department of John Wanamaker, New York, and received a salary of $10,000 per annum and in addition yearly bonuses of something in excess of $2,000. He was physically strong, of exemplary habits, frugal and industrious, and had good prospects for advancement.

There survived Mrs. Tesson her three children by her first marriage, viz.: – William Atkins, who testified in October 1923, that he is a laborer with a wife and nine children ranging in age from 16 months to 27 years: Charles Atkins, who testified in October 1923, that he is a laborer with a wife and one child, a daughter 19 years of age; and the unmarried crippled son, Roy.

There survived Mr. Tesson his mother, Emily Duncan Tesson, now 85 years of age, and a brother and two married sisters, all of whom are mature and have established homes of their owns , all of these claimants being American nationals at the time of and ever since his death.

Each of the three sons of Mrs. Tesson received from her separate estate approximately $1,800. Mr.Tesson’s estate inventoried at approximately $11,500. He carried three policies of insurance on his life for $5,000 each payable “to his wife, Alice E Tesson, if living, if not, then to the Assured’s executors, administrators or assigns”. The proceeds of these policies were claimed by the administrator of Mrs. Tesson’s estate.

After litigation, the highest court of the State of New York decided that it must be assumed that Tesson and his wife died simultaneously, and hence by the terms of the policies they were payable to the administrator of Mr. Tesson’s estate. That estate, including the proceeds of the life-insurance policies mentioned, after paying all expenses of administration, was of the net value of $22,828.80, which was distributed in four equal parts to Tesson’s mother, brother, and two sisters, none of whom, according to stipulation filed the life-insurance litigation, had been dependant upon Tesson for support. There is however, in the record an affidavit of Tesson’s mother made in December, 1923, to the effect that her deceased son Frank subsequent to the year 1909 contributed approximately $500 per annum towards her maintenance. She had never lived with her son, but at the time of his death she was and long had been residing with her daughter Mrs. Makinney, of Alton Illinois.

It is evident from the record that if either Tesson or his wife had lived her crippled son Roy would probably have continued to receive small contributions of not more than $25 per month for his maintenance and support. Such a remittance was made by Tesson to William Atkins for the use of Roy on April 30, 1915, the day before taking passage on the Lusitania.

There was lost with Mrs. Tesson on the Lusitania personal property of the value of $2,325.00. No claim is put forward by the administrator of the estate of Frank B. Tesson for property lost with him. The awards which this Commission is empowered to make in death cases are based, not on the value of the life lost, but on the losses resulting to the claimants from the death, in so far only as such losses are susceptible of being measured by pecuniary standards. Bearing this in mind and applying the rules announced in the Lusitania Opinion and in the other decisions of this Commission decrees that under the Treaty of Berlin of August 25, 1921, and in accordance with its terms the Government of Germany is obligated to pay to the Government of the United States on behalf of (1) Roy Atkins the sum of five thousand dollars ($5,000) with interest thereon at the rate of five percent per annum from November 1, 1923, (2) S. Stanwood Menken, Administrator of the Estate of Alice E Tesson, deceased, the sum of two thousand three hundred and twenty five dollars ($2,325.00) with interest thereon at the rate of five percent per annum from May 7, 1915, (3) Emily Duncan Tesson the sum of three thousand dollars ($3,000) with interest thereon at the rate of five percent per annum from November 1, 1923: and that the Government of Germany is not obligated to pay any amount on behalf of the claimants in these two cases. Done at Washington February 21, 1924.

Edwin B. Parker, Umpire United States of America on behalf of S. Stanwood Menken, Admisitrator of the Estate of Alice E Tesson, Deceased, and William Atkins, Charles Atkins, and Roy Atkins, Claimants, v Germany Docket Nos. 217 and 293 United States of America on behalf of Andrew C. McGowan, Administrator of the Estate of Frank B Tesson, Deceased, and Emily Duncan Tesson, Bertha Angeline Montgomery, Lillian Josephine MaKinney, and John Williamson Tesson, Claimants, v. Germany Docket No. 544 Parker, Umpire, rendered the announcement following:. This case is before the Umpire for decision on a certificate of the two National Commissioners certifying their disagreement. In the cases are numbered and styled as above which were consolidated, a final decree on the decision of the Umpire was entered by this Commission on February 21, 1924. The claimants in the first case have presented through their attorneys to the American Agent a petition for the rehearing praying for an additional award, which has been called to the attention of the Umpire. The rules of this Commission make no provision for a rehearing of any case in which a final decree has been entered. However in deference to the earnest insistence of eminent counsel the Umpire has carefully reviewed the record in these cases in the light of the petition for rehearing. But he finds nothing in either record or the petition which had not been taken into account and carefully weighed before the decision was rendered.

The instant petition apparently fails to take into account and correctly appraise the pertinent considerations following: (1) The claim is grounded on damages alleged to have been sustained by claimants resulting from the death of Alice E Tesson, who, with her husband, went down with the Lusitania, the two dying simultaneously. They both died intestate. (2) Mrs. Tesson’s separate estate amounted to approximately $5,400 and was inherited equally by the claimants William, Charles, and Roy Atkins, her sons of a former marriage. Mr. Tesson’s separate estate, supplemented by insurance on his life collected by his administrator, aggregated $22,828.80, which was inherited by his mother, brother, and two sisters. (3) At the time of their deaths Mrs. Tesson was 60 years of age and her husband 49 and his life expectancy therefore much greater than hers. (4) Mrs. Tesson derived no income from her personal efforts and it is not established that she possessed any pecuniary earning power. Such contributions as she made to her children were made from her husband’s earnings. Her two oldest sons, William and Charles, were 39 and 38 years old at the time she died and were able-bodied and had domestic establishments of their own. They were not dependent upon their mother to any extent. The contributions which she made to them were in the nature of occasional gifts, alleged to average $300 and $200 per annum to William and Charles respectively. (5) It was Mr. Tesson’s death that cut off the source of the contributions which their mother had made to these three claimants, who were not his children. (6) The argument that the claimants through their mother’s death have lost the insurance on Tesson’s life, which was payable to her in the event she survived him, aside from being legal contemplation too remote to support a claim for damages, ignores the realities. Tesson and his wife died simultaneously. His life expectancy was greater than hers. He made no provision that the policies should be payable in whole or in part to the claimants or any of them in the event his wife did not survive him. The payments were in fact made to his heirs. The argument put forward on behalf of these claimants amounts to a complaint that one group of American nationals (Tesson’s heirs) benefited at the expense of another group of American nationals (these claimants) because Mrs. Tesson died simultaneously with her husband. Germany cannot be held liable because she did not survive him but only for damages suffered by claimants proximately resulting from her death. (7) It is not permissible to speculate with respect to the pecuniary effect on claimants had their mother survived Tesson or had Tesson survived her. The fact is, as a competent court of last resort has found, they died simultaneously and the claimant’s demand is based on the pecuniary damage suffered by them resulting from their mother’s death. (8) But if it were competent for this Commission to indulge in such speculations they would not lead to a different result. Had Tesson been lost with the Lusitania and his wife survived, it is apparent that her interest in his small estate and her smaller estate, supplemented by the insurance on his life which was for her benefit should she survive him, would scarcely provided for her own needs and would have not put her in a position to make any substantial contributions to her sons. On the other hand, had Tesson survived his wife the record does not justify the conclusion that his contributions to the sons of his wife would have exceeded the equivalent of the award made. (9) Not withstanding this state of the record the Umpire in his opinion of February 21,1924, said: ‘It is evident from the record that if either Tesson or his wife had lived her crippled son Roy would probably have continued to receive small contributions of not less that $25 per month for his maintenance and support.’ An award was accordingly made on behalf of this son Roy, who was 28 years of age when his mother died, in the sum of $5,000 and a further award on behalf of the administrator of Mrs. Tesson’s estate for $2,325, the value of her personal property lost, with interest on both amounts. (10) In this state of the record no award was justified on behalf of Mrs. Tesson’s sons William Atkins and Charles Atkins. The petition is found to be without merit and is hereby dismissed. Done at Washington August 31, 1926. Edwin B. Parker, Umpire.

….among the passengers who are believed to have perished is Miss Henrietta Pirrie.

Miss Pirrie is known to have been one of those who sailed on the ill fated liner, and as her name is not included on the list of survivors it is feared that she has been drowned. This surmise is confirmed by the fact that her parents have received a telegram from Cunard stating their regret that her name is not mentioned among those saved.

Miss Pirrie, who was only twenty-one years of age, was born in Perth where her parents resided until some time ago. She left Scotland a few years ago to take up a position in the household of the Duke and Duchess of Connaught at Government House, Ottawa.

She was coming home to Scotland on holiday, and there is a tragic coincidence in the fact that following upon the telegram from the Cunard Company there came from her a characteristically cheery postcard which had been mailed from New York the day before she sailed and was only received in Glasgow yesterday.

Family and friends of those never found were left to ponder a wide variety of equally unpleasant scenarios. Had their missing one been among those, drifting in deepening shock, never found after sunset? Had he or she died of exposure and exhaustion, without a lifebelt? And, worst of all to contemplate, had the lost one been trapped below decks and carried down with the ship as she sank?

Richard Preston Prichard

The family of victim Richard Preston Prichard was determined to find out what had become of him, if the question could be answered. His mother was haunted by the thought that he had never gotten clear of the ship. She, and his brother, Mostyn, wrote to every survivor for whom they could obtain an address. They enclosed a missing person poster, and in their letters would request any information that the recipient might be able to furnish regarding Richard.

The letter writing campaign yielded several hundred results, on file today at the Imperial War Museum. Richard was a medical student at McGill University in Toronto, returning to his native England to enlist. He traveled in second class. He was neither famous nor notorious. But, because his family asked while memories were still fresh, he was well remembered. The cumulative effect of the letters is both charming and very sad, as dozens of people recounted their memories of Richard’s final week.

Survivor Thomas Sumner recalled that on sailing morning he and Richard had stood side by side at the rail, with Richard taking snapshots with his Kodak-type box camera. They had a talk about cameras while at the rail, and subsequently maintained a casual friendship through the crossing. He remembered that Richard was always pleasant, and had participated in the obstacle race and the tug- of- war. A mutual friend of theirs, a Miss Hardy, had taken snapshots on the crossing including several group shots with Richard in them. Not only had Miss Hardy survived, but so too had her camera. Sumner had seen the photos, and urged Mrs. Prichard to write to Miss Hardy for further details. Miss Hardy eventually responded that the pictures had not come out, and would be of no use.

Olive North recalled that she and some young women had been playing a rope game on deck, and that Richard appeared on scene and was able to ‘lasso’ her quite efficiently. He explained that he had spent time on a ranch in western Canada and had acquired the skill there.

Norah Bretherton remembered that Richard was in charge of collecting the scorecards at the second class whist tournament, which she had won.

Both parties involved documented a rather interesting bit of casual rivalry at Richard’s dining room table. Miss Meta Moody, who lost her mother in the disaster, wrote Mrs. Prichard a friendly letter in which she acknowledged sitting with Richard at meals, and described him as a pleasant table companion. Miss Grace French, who sat at the same table, wrote Mrs. Prichard numerous, painstakingly detailed, letters. It is obvious from these letters that Miss Moody and Richard had hit it off and that Miss French did not care for Miss Moody at all. Grace described her in unflattering terms, although photos show Meta Moody to have been quite pretty. Grace French mentioned that once it was established that Prichard and Moody had a lot in common, conversation at the table was dominated by their talks of travel, and of California where they had both lived.

Richard, who Miss French described as being handsome, charming, sunburned, and full of life, apparently flirted with Grace on May 7th. He told her, over lunch, that there was another girl in second class who looked exactly like her and that if she, Grace, would meet him on deck after lunch, he would point out the look-alike. He went below to change into his dark green spring suit and get a hat, and Grace French went on deck to wait for him. The torpedo struck soon after, and she never saw him again.

Arthur Gadsden, Prichard’s cabin mate, confirmed part of Grace’s account. A few minutes before the disaster commenced, he returned to his cabin and found Richard changing his clothing and packing his suitcase.

The final known sighting of Richard during the disaster was by Alice Middleton. She explained to Mrs. Prichard that, at the end, she was on the promenade deck, hysterical, her “reason all but gone.” Richard had appeared, calmed her, and helped her up a flight of stairs to the boat deck, off which they were immediately washed as the ship sank from under them.

A running theme in later accounts sent to Mrs. Prichard suggests that, at some point, she received a letter, now lost, describing Richard dying on one of the swamped collapsibles. Many writers told Mrs. Prichard that, yes, people did die aboard the boats, but that they were neither thrown overboard to lighten the load, nor taken aboard rescue ships. No one in the surviving letters recalled seeing Richard die while awaiting rescue, but Mrs. Prichard’s sudden interest in that aspect of the disaster leads us to believe that at some point a correspondent said that he or she had witnessed his death.

Crew members, friends, strangers with good memories, all supplied dozens of minute details of what Richard Prichard said, wore, ate, and did during his last days. Of equal interest, are the dozens of letters by those who had no recall of Mr. Prichard, but who wanted to take the time to assure his family that the tales of panic in the press were exaggerated. Most emphasized that it was nearly 100% certain that Richard could not have been trapped below deck. Mrs. Bretherton wrote that although five months pregnant, she had been able to run from B deck to the boat deck, and from the boat deck to her C deck cabin and back again, with little difficulty. Miss Maycock assured her that the men had behaved splendidly and that, if nothing else, Mrs. Prichard could be assured that her son had died with dignity. She then appended that she spoke only of the male passengers: the crew had been horrible.

Several of the grieving mothers, among them Mrs. Ferrier, Mrs. Pye, and Mrs. Adams wrote to Mrs. Prichard “woman to woman” about their experiences on May 7th, and to extend their sympathy to a mother who had lost an adult child. Violet Henderson shared the observation that although she and her boy, Huntley, had no life jackets and could not swim, they survived in the water, while her brother and sister in law, Mr. and Mrs. Yeatman, who could swim, and who did have preservers, were both lost. A few letters strike the reader as being quite odd. Martin Mannion wrote that he had little doubt that Richard had, in fact, been trapped below decks and died horribly, like a rat in a trap. Oliver Bernard’s letter is a hectoring, aggrieved missive and the least appealing of the cache.

Richard Prichard, a pleasant but obscure young man, is the most exhaustively documented passenger aboard the final voyage.

Mother died peacefully. Buried in Queenstown.

~Sidney and Frank.

With those words the five-day wait of Reverend W. Edward King, of Lockport, Illinois ended.

His wife, Martha, had departed for New York on April 29th, destined for a reunion in England with two of her sons; both bankers in London. Four children remained behind in Illinois.

The Kings were new to Lockport. Reverend King had taken charge of the Lockport Congregational Church in June 1914, after having served in the same capacity at Seward, Illinois for several years. They had begun to establish roots in the community, and congregation members described Martha King as a tireless worker and a dominant force in the operation of the church.

Mrs. King was, apparently, one of those who survived the sinking and long immersion, but who was in irreversible shock by the time she was pulled aboard one of the rescue vessels. Reports were contradictory as to whether she died during the voyage to shore, or in the hospital shortly after arrival. Reverend King said, through intermediaries, that the wording of their sons’ telegram implied to him that she had died in the hospital. He also declined to make himself available for interviews until after his sons had sent a full report of what happened.

If the sons did send a detailed report, the press did not follow through. A search of relevant newspapers shows that hometown reporters never again interviewed Reverend King on this point .

Lockport schools closed early out of respect for Martha King on the day of her memorial service, which students were encouraged to attend. Congregation members sang solo renditions of her favorite hymns. Thirty old friends from Seward made the trip to console Reverend King. Martha’s body was not shipped back to the United States, but was buried in a private grave in Queenstown.

The Cunard Confidential Report of 1916 contains detailed capsule descriptions of the unidentified bodies buried in Queenstown and elsewhere. In many cases, the John Doe or Jane Doe retained so many clues helpful in identification that something very sad is hinted at: everyone who could have identified this man or woman died with them.

146. Male, 27 years, brown hair, clean shaven, height 5’ 7.” Wore blue clothes and black tie.

Property: 1 gold watch, with leather guard; 7 shillings in silver; 9 foreign coins; 1 penknife; 1 stud; 2 links; 1 fountain pen (Waterman, medium point nib); handkerchief; also unfinished letter commencing “Dear Ted, We hit New York at 7:30 in the morning, and after seeing to our luggage we made our way to Bronx Park to visit some friends of mine…”

167. Female,30 years, grey eyes, brown hair, short thick nose, round face, stout make, height about 5’ 1”. Wore white silk blouse and cream dress, patent leather boot (buttoned) with cloth uppers.

Property._ 1 brooch with 5 stones (1 centre and 4 outer); 1 wedding ring (18 carat), N0.9095 scratched inside, maker’s name evidently “Hemsley;“ 1 engagement ring, with 3 white and 2 blue stones; 1 keeper ring with 3 green stones and 2 white; 3 rings; and 1 metal brooch with 5 stones.

221. Male. 5 or 6 years, round full face, broad high forehead, small mouth, blue eyes, well shaped features. Wore while woollen singlet and white cotton combinations, check jacket and knickers of same pattern, pink woollen jacket outside with dark ivory buttons, black button boots with black socks, and patent leather belt.

Property. Gold ring with initials “J.W.P.” worn on second finger of right hand.

222. Male baby, 12 to 16 months, round chubby fat face, hair inclined to be red, small short nose, sunken eyes, prominent forehead, sucking tube fastened round neck with cord. Wore white woollen wrapper, white cotton bodice having red and blue stripes round edges, blue cotton overall fastened at back with white buttons and plaited down front, embroidered with dotted squares, coarse grey woollen outside jacket, with 4 ivory buttons, black stockings, shoes and straps.

253. Male body, washed ashore at Kilcumin, July 17th. Very decomposed, and face unrecognizable.

Property.- Pocketbook, marked ‘Compliments, Savings Dept., The Union Trust Co., Ltd., Toronto,”; pen knife; note book (apparently) with few indistinct entries; cigarette picture of M Maeterlink; 4 plain cigarette holders; 1 ten cent Canadian coin; and two lead pencils.

Buried on beach above the high water mark, Kilcumin Strand, Brandon Bay, Co. Kerry, July 19th.

11. Female body, washed ashore at Ross, Carrigaholt, July 20th. Body very decomposed, breast bones, legs and arms missing, teeth in upper jaw were sound and regular, except two molars on left side, which were gold filled. There were three teeth missing in left side, and one on the right side, which had been extracted before death. The two front teeth had been knocked out since death. Besides the body, there was a corset, maker’s No. 6110955 with letters “N.H.” marked on it in ink. Pieces of white silk underclothing were adhering to the body, on one of these was printed “Niagara Maid” probably maker’s trade mark, on another piece the letter “J” and other pieces not decipherable were marked in black thread.

Mike Poirier

Mike Poirier