The Lusitania : Part 13 : The Morning After: Post Traumatic Stress

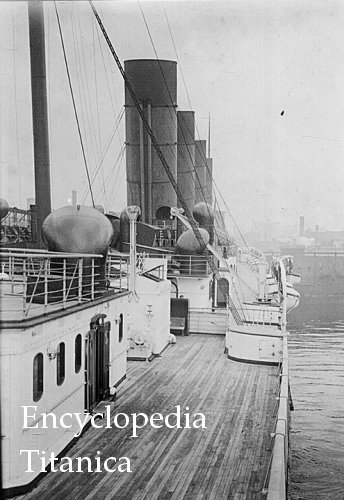

A deck view in Second Class

Jim Kalafus Collection

The Lusitania survivors, with the exception of the most seriously injured, resumed their journeys, and their lives, within a few days of the disaster. They were carried by ferry to Liverpool, and then by train to destinations across the United Kingdom and Europe. Press interest in specific survivors soon faded, and life returned to normal for the Lusitania’s people. However, the disaster left unpleasant legacies for many of those fortunate enough to survive.

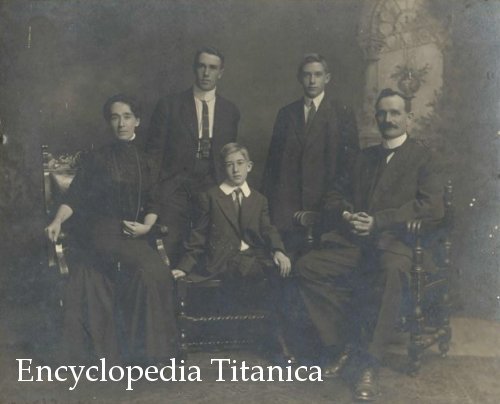

The horrors of W.W.I had not yet exposed the world to the concept of shell shock and what would one day be called Post Traumatic Stress Disorder. Generally, depression, guilt, nightmares, panic attacks, and prolonged melancholy were perceived as signs of individual weakness, malingering, attention seeking, hysteria and, among men, cowardice. Stoicism was an admired trait, and was considered to be a keystone of both English and American national character. Belle Naish wrote glowingly, in several letters, of Robert Kay, 10, who cried but once for his lost mother. She considered him to be both a sustenance and example to her, and to others, with his manly behavior.

Robert Kay and family

Michael Poirier Collection

Survivors returned to the inner circles of their families and their home communities, where they were greeted with love and thanksgiving, and were then expected to continue with their lives to the best of their abilities. No grief counseling. No support groups. No telephone hotlines. It was not that people were treated with intentional cruelty or harshness, but it was an era in which feelings were internalized and the best course of action was thought to be “pick up, dust off, and move forward.”

The vast majority of Lusitania survivors did go on to lead normal lives. They coped, as best they could, with the memories and the nightmares; each discovering their own way to put the horrible things they once witnessed behind them. Arthur Scott, who survived because his mother, Alice, placed him into one of the few boats to get clear of the ship, coped with the loss of his mother by never discussing the Lusitania at all. His own children did not know he was a survivor until, as adults, they were contacted by English relatives. Mike spoke with the Scott family a few months before Arthur passed away, and they respectfully requested that we not approach him for an interview about the disaster; a request we understood and honored. Other survivors coped by facing the disaster head on; many discussing the events at every opportunity and granting every interview request for the rest of their lives. However, for a few, the events of May 1915 proved too horrible to assimilate.

|

| Gerda Neilsen Jim Kalafus collection |

|

| Gerda Nielsen John Welsh Wedding Photo Jim Kalafus Collection |

When Gerda Welsh was pronounced dead on June 2, 1961, it was a sad end to a tragic life.

Mrs. Welch was born in Norway, circa 1885, as the youngest child of Thomas Neilsen, a seaman. His wife died soon after Gerda’s birth, leaving him to raise her, and her older sister Thomasine, by himself. The Neilsen family relocated to South Shields, England, from where Gerda, a skilled dressmaker, immigrated to the United States in 1910. She contacted a friend in Brooklyn, Mrs. Gabrielson, who agreed to house her when she arrived. She set sail on the Mauretania, which docked in New York on October 7, 1910. The following four and a half years of her life are difficult to document, other than that she continued working in New York City. She booked passage aboard the May 1st. crossing of the Lusitania to visit her sister Thomasine, who still resided in South Shields.

John Welsh had traveled halfway around the globe in order to board the Lusitania. He had been working forseveral years in Honolulu, Hawaii, as a mechanic with the Marconi Wireless Telegraphic Company. He was returning to Groton, near Manchester, England, with his savings of several thousand dollars.

Welsh was not aboard the ship long when he noticed Gerda. She stood about 5’6”, had fair hair and blue eyes. She noticed him as well and they soon struck up a conversation. “We took a strong fancy to one another,” he later declared.

John and Gerda became acquainted with the Hook family during the course of the voyage, and shared their table at meal times. One of the main topics of conversation was the threat of being torpedoed. “If the worst should come,” John said, “we made up our minds to sink or swim together.” Towards the end of the voyage, “we became engaged, arranging to be married on arrival.”

“When the ship was struck, I was with my young lady, and we stuck to one another till the vessel sank.” John Welsh recalled. He escorted Gerda to one of the last lifeboats after a lifebelt on her. The boat upended, and he jumped into the sea to rescue her.

“In the water, she was braver than any man I’ve ever met. She encouraged me whilst I swam… I supported her in the water for half an hour till we reached a lifeboat. The people in the boat did not want take her in, but relented.” To Gerda’s horror, the men who lifted her into the boat wanted to leave John behind, claiming that the craft was too crowded to bring him aboard. “She pleaded with them, and finally they pulled me up.” He claimed that he “sustained some slight injury to my leg and arms.” A tugboat rescued their lifeboat, and they landed in Queenstown later that night.

Talking to a reporter from the Irish Times, he said, “Here we are together safe and sound, and the wedding bells will soon be ringing.” They took the ferry to England, and in less than a week were married at the All Saints’ Registry Office. The ceremony took place on Thursday, May 13, 1915.

The couple settled in at his home, 31 Carlton Terrace, Gorton. Their happiness unraveled, as they were unable to conceive any children. The memory of the Lusitaniaconstantly played over in Gerda’s mind and she slowly went insane. Finally, John saw no other choice but to commit her to a mental hospital. There was initially hope that she might come out of her “condition”, but she never seemed to improve. John moved away to find work after several years.

Gerda died on June 2, 1961.

Dr. Daniel Virgil Moore, Creighton University graduate and lately a resident of Yankton, South Dakota, gave a spare deposition from Dublin Hospital:

Dr. Daniel Virgil Moore, Creighton University graduate and lately a resident of Yankton, South Dakota, gave a spare deposition from Dublin Hospital:

1. Noticed ship running in serpentine course at about one o’clock. At that time we could observe no cause for swerving.

2. During the following twenty five or forty minutes, the ship resumed her usual or straight course many times. She was coursing straight more than half the time.

At one time the ship swerved so violently, she listed much to starboard side causing many to stagger.

3. During this time I observed an oblong black object, about two and a half miles from our port side. It trooded (sic) as fast as the ship for a while, then fell behind. It disappeared two or three times. It appeared to have three or four dome-like projections, many saw it. It was the general opinion that it was a friendly submarine.

4. I went to luncheon at about one forty o’clock. I ate very lightly and was leaving the table at the time of the report. The report sounded liker a muffled bass drum. The ship quaked like a house following heavy thunder.

5. The list toward starboard was marked within ten seconds. I do not remember hearing a second report.

A second, more detailed account by Dr. Moore exists, as well:

The first abnormal thing I noticed was a zig-zag swing of the Lusitania. This occurred about one o’clock in the day. It attracted the attention of several of us, and with the aid of glasses we observed in the distance some two and a half miles away, what seemed to be a black object with four apparently dome-like projections. This object cruised along swiftly at times, then slowed down, disappeared and re-appeared. During all this time, the Lusitania continued to zig-zag. The distant object finally disappeared, and our ship continued on an even course at what I judged to be a speed of about eighteen knots.

The conclusion we came to was that it was a submarine, and that it was a friendly one or the Lusitania would not have gone back to an even course.

At 1:40, I went down to lunch, and the only other vessel observable in our vicinity was a fishing smack. The land had been distinctly visible for more than three hours previously, about, I think, twelve miles distant. At lunch there was some discussion about the objects seen, but everyone was calm and confident.

There was a muffled drum-like sound coming from the direction of the bows of the Lusitania, accompanied by a tumbling motion of the ship. Immediately afterwards, the Lusitania began to list to starboard. With such startling suddenness did it come, that we felt the heavy list before we were able to make our way out of the saloon. There was some general exclamation among the women when the noise of the impact was heard, but the men present did everything they could to reassure them. They started leaving the saloon in good order.

As I reached D Deck, I found myself in difficulty, owing to the list, which was at a very sharp angle. With other passengers I did my best to scramble to the Promenade Deck. There was no crushing, and it was entirely owing to the tilt that one’s progress was not easier.

I looked over the bulwarks to see whether I could discern evidence of the use of explosives. Beside me was a young woman struggling for her life. I recognized her as a girl who had sung at one of our concerts aboard. I gripped hold of her and got her into the boat. A moment later I was able to render a man similar help. At this juncture somebody shouted “For God’s sake, shove off, or you will go down in the suction.”

I got oars and in an almost despairing effort pushed off the boat into which I had scrambled. We drifted about fifty yards. The water was then lapping over the sides of the Lusitania and I could see that she was filling very fast.

It was necessary to bail out our boat in order to keep her floating, and I used my hat for the purpose. We did not seem to make much progress, and I clearly realized that our craft was becoming rapidly submerged. Noticing a keg lying in the bottom of the boat, I threw it out and, flinging myself over the side, I reached it and clung to it. Not far off was a young steward supporting himself by a deck chair. I urged him to let go of it and cling to the keg with me. He did so and we both hung on to it. Eventually we were picked up and taken to Queenstown.

Daniel Moore had faced his first major disaster in 1906 when, as a young graduate student, he went to San Francisco in the immediate aftermath of the great earthquake. He studied at Columbus Hospital in New York City, under Mother Cabrini, from 1910 thru 1911. He did ambulance work at the Triangle Factory fire on March 25, 1911; most likely ferrying away some of the dozen fatally injured women who initially survived the jump from the burning ninth floor. His diploma, signed by Mother Cabrini, was a treasured possession he lost with the liner.

Moore remained under a doctor’s care in Ireland for over a month. The formerly capable surgeon suffered from cardiac distress, chronic head pains described as ‘sinus infections,’ palpitations, and ‘neurosis’ so severe that he required an additional eighteen months of medical attention. He remained so ‘nervous’ that he could not resume his practice forseveral years. His ailments read, to a latter day observer, like a catalogue of severe panic attack symptoms. The U.S. Mixed Claims Commission later granted him a $10,000.00 judgment against Germany, for the disruption of his once flourishing medical career.

Dr. Moore established a new practice in Sioux City, Iowa, in 1920. He maintained it through 1948 and, for a time, kept a second practice in his birthplace, Fremont, Nebraska. His sister, Mary, kept house for him.

Mary Moore died in 1939. The never-married doctor described himself as “alone and lonely” in a 1940’s interview. He died in Sioux City in early 1953, at age 73, after an illness of five years, and was returned to Yankton for burial. He had outlived six brothers and sisters, and at the time of his death, his only living relative was a niece.

Allan Beattie, 18, of Winnipeg, Manitoba, Canada may have experienced his second personal tragedy involving a shipwreck when he and his mother, Geneva “Grace,” went down with the Lusitania. According to 1915 accounts, three years before, his uncle, Thomson Beattie, died of exposure aboard the Titanic’s swamped collapsible A.

A Beattie family history, online, shows that Allan’s father and Thomson Beattie were not brothers, but that does not rule out the possibility that they were cousins, or more distantly related. A detailed list of those who attended Thomson’s memorial service in Winnipeg does not contain the names of any member of this particular Beattie family branch.

Allan was a clerk in the offices of the Winnipeg Street Railway, while his mother was a prominent philanthropist who had recently begun war-related work. The Beatties were bound for Scotland, where they planned to visit Captain J.A. Beattie, husband and father, who was a Chaplain of the 79th Cameron Highlanders of Winnipeg. Neither found their way to a lifeboat, and when the ship sank, they were pulled down with it, tangled in a mass of rope. Beattie freed himself and managed to surface, but his mother, wearing a lifebelt, did not.

Chaplain Beattie was quoted a few days after the disaster:

I was a cowboy for thirty-five years on the plains of Canada, and I can shoot the buttons off a man’s coat at one hundred yards. When I came to England I had no intention of using my marksmanship against the enemy. But now, with my revolver, I will consider it my duty to kills as many Germans as they killed in the sinking of the Lusitania. I only wish I was of a different nationality, so that I could go to Germany and there take out my satisfaction on the Kaiser in person. It was nothing but wholesale murder of women and children. I count myself no less a Christian or churchman for thinking as I do.

Allan Beattie, like Gerda Welsh, had difficulty escaping from the shadow of the Lusitania. He was rejected by the Armed Forces due to poor eyesight, and passed through a succession of jobs before having a breakdown in 1920. A second breakdown followed in 1921, and reference was made to a third and fourth having been suffered prior to 1926. He worked for a time as a reporter for the Winnipeg Tribune. His father remarried, to a woman with whom Allan could not get along, and a distance grew between father and son. Allan Beattie drifted between several cities in western Canada, never managing to settle down or hold a job for any appreciable period of time.

Former employers testified on Beattie’s behalf, during his suit against Germany. They swore, under oath, that his mental condition made it difficult to retain him as a long term employee and substantially reduced his earning potential within the jobs he obtained. Commissioner Pugsley, offering his decision regarding Beattie’s claim against Germany in the Canadian court system, stated: There is no doubt this young man suffered severely as a result of his experiences, and while it is difficult to assess the monetary extent of the damage sustained, the statements on file from employers to the effect that had he not been suffering from extreme nervous conditions he would have been earning a larger salary tend to substantiate the claim. I allow for this item…$15,000.00.

Allan Beattie managed to turn his life around following this public humiliation. He purchased a movie theater, apparently with his settlement money, and as of 1935 was prospering.

He died at age 72, in Miami, Florida, in April 1968.

Jessie Taft Smith’s short and tragic life began in Braceville, Ohio on February 12, 1876. She was one of three children born to Hobart and Mary Taft. The Tafts were quite prominent,- theirs was one of the pioneer families of the small town, and it was no surprise when Jessie became engaged to John W. Smith, also from a well-to-do local family. They married on October 2, 1901 at the local Methodist Church, and following their honeymoon, they settled in Chicago.

Jessie Taft Smith

John Smith was an inventor and one of his accomplishments was an internal combustion

airplane engine of his own design. The French Aviation Corps was using his engines in their planes by 1915, and the British Admiralty contacted John about developing similar engines for them as well. He left for England in January of 1915 to work on the “Smith Engine.”

Jessie was lonely and moved back to Braceville to be with her family. Her husband summoned her to England, requesting that she bring his blueprint plans for the “Smith Engine.” He cabled the Cunard agents 30 pounds to pay for Jessie’s passage on the Lusitania. She boarded the ship on May 1, 1915 and was assigned an inside cabin, B-20.

Not much is known about her day- to- day activities, but on May 7, she had her lunch and adjourned to the writing room. Shortly after two o’clock, she heard a noise and then felt that the Lusitania “seemed to lift”. She then noticed, “another explosion occurred”. She made her way forward towards the main staircase. She was told, “Not to hurry as there was no danger”. She may have had an inkling of what was to come, for on a previous day she had made sure that her lifebelt was in a handy spot in her cabin.

Darting into her cabin, she placed the lifebelt on and ran back towards the staircase. She exited the companionway onto the starboard boat deck. A steward helped her into boat 13, and within a few minutes it was lowered. Jessie turned around as soon as the boat pushed off, so she couldn’t see the sinking ship, which disappeared a few minutes later. The boat picked up several people from the water, and was eventually taken in tow by a fishing boat.

Wesley Frost, the American Counsel, met Mrs. Smith on the wharf and handed her over to Dr. Townsend and his wife, who took her into their home and cared for her. John Smith learned about the sinking while in Birmingham, and was soon relieved to get a telegram from his wife. He arrived in Queenstown on Sunday and took her back to England.

Jessie seemed fine at first. She took Sunday excursions to Sutton Park, and walked long distances in the surrounding woods. However she began to unravel over the next few months, despite the constant care of physicians. Her husband spent most of his time with her and neglected his work, which contributed to the British Admiralty’s rejection of his engine. Jessie finally suffered a complete nervous collapse in February 1916, and was sent to the South Hill Nursing Home in Birmingham. Her family claimed it was due to her experiences on the Lusitania, and also rheumatic fever.

She eventually recovered enough to make the journey home: The Smiths booked passage on the New York, and arrived in the United States on July 31, 1916. Jessie moved back to her father’s farm, where her brother Robert, who was a doctor, and her sister, Florence, cared for her. The Smiths brought their case before the Mixed Claims Commission, but Commissioner Parker found the evidence regarding their financial losses to be sketchy, at best, and awarded her only $1,196 for lost effects on October 24, 1924. The couple felt they deserved more and contested Edwin Parker’s decision. Finally, on December 30, 1924, Parker awarded an additional $2,500 in compensation.

The Smiths moved to Philadelphia where, on November 1, 1928, Jessie Taft Smith passed away at age fifty-two. Her body was transported back to Newton Falls, and she was buried in Braceville Cemetery after a brief memorial service.

Angela Pappadopoulo Angela PappadopouloThe Daily Sketch Jim Kalafus collection |

Angela Pappadopoulo, of Athens, Greece, remains one of the best-remembered Lusitania survivors. She was a striking woman, and a number of different photos of her taken in Queenstown ran in the newspapers. This letter, written by Lusitaniasurvivor James Baker to Robert Timmis, also a survivor, just over a week after the sinking, is the best surviving account of Mrs. Pappadopoulo’s experiences, and provides a touch of gallows humor as well:

15 May 1915

Dear Timmis, I have been so full up with callers and letters and having Mrs. Pappadopoulo to look after that I have not been able to write you… I had a call yesterday from Bistis’ brother. He had been over to Queenstown but found no trace of his brother. He saw a steward who informed him that both Bistis & Pappadopoulo were in a boat that was being lowered just as the ship was sinking. The boat was smashed and they were upset and thrown into the water and were struggling in the water. Bistis tried to help Pappadopoulo to get into the boat, they held on for a while and disappeared.

I have had a pretty bad time with Mrs. Pappadopoulo. I took her home at first, and then some friends of his offered to take her, but, as she grew worse, would eat nothing and had hysterical attacks I decided to put her into a nursing home, and am glad to say that she is now quite calm, but very weak. I hope that by Tuesday she will be well enough to start for Paris and Athens…

P.S. Since dictating the above, Mr. Baker has heard that the body of Mr. Pappadopoulo has been recovered and had to leave the office to go and see Mrs. Pappadopoulo and learn her wishes. He is therefore unable to sign this letter himself.

The gallows humor comes, of course, from the time frame in which the events in the letter took place: Angela Pappadopoulo’s breakdown, hospitalization, recovery and anticipated train-and-ship journey back to Greece, took place between her arrival in London on May 9th and the dictating of this letter on the 15th. Reading between the lines, it does not seem that she was spoiled with excessive sympathy.

Albert Jackson Byington was a 40-year-old electrical and mechanical engineer, en route to London, in May 1915. He had spent the previous ten years working in Sao Paolo, Brazil. His promotion, construction, industrial and fruit growing operations were on a considerable scale, and he was traveling to England aboard the Lusitania in the interest of one of his Brazilian ventures.

Mr. Byington testified to being thrown down sixty feet, from the sinking ship. He was likely in boat #20, with Ogden and Mary Hammond. He injured his spine, landing on his back in the fall, and was pulled from the water in severe shock.

He remained in London for nineteen days, before journeying back to Sao Paolo. However, he was no longer the efficient manager he had been before the disaster. He suffered from impaired memory, loss of initiative, loss of decision, and “general impairment” of mental faciltiites as the result of his experiences aboard the Lusitania.

The Mixed Claims Commission awarded Albert Byington $10,000 in 1924, although they stated that there was little evidence in the way of medical records, or doctors’ affidavits, to suggest that he was still suffering from the after effects of his general breakdown at that point. They noted that the last papers pertaining to treatment for any disability stemming from the Lusitania disaster dated from December 1918.

Albert Jackson Byington died in Naples, New York, on September 17, 1951, at the age of 78.

|

|

| Beatrice and Alfred Witherbee Jr. Courtesy Lawrence Jolivet |

|

|

|

| Rita Jolivet Jim Kalafus Collection |

|

|

|

| Beatrice Witherbee (right: in San Remo). Courtesy Lawrence Jolivet |

|

Beatrice “Trixie” Witherbee, of New York City and London, was another survivor who found coping with the memories of May 7th, 1915 too much to bear. However, unlike Gerda Welsh, she was able to pull herself out of the downward spiral, and lived to experience a happy ending.

Beatrice arrived in NYC aboard the last completed voyage of the Lusitania in April 1915. She had traveled to London to join her husband, A.S. Witherbee, and establish her new household in The Savoy to her liking. She returned to the United States to escort her mother, Mary Cummins Brown, and her son, Alfred Scott Witherbee Junior, to their new home. Her brother in-law, Sidney Witherbee, attempted to persuade Beatrice to switch her booking from the Lusitania to the New York while visiting with her at the Biltmore Hotel the evening before departure, but to no avail. A second attempt on the morning of May 1st. proved equally futile.

Several passengers and crew were charmed by Mrs Witherbee’s attachment to her son, and left written accounts of their day-to-day life during the voyage. Beatrice was so devoted to her son that she violated protocol by having him seated with her in the first class dining room. However, no record survives to tell of what became of the small family group after the ship was torpedoed. Beatrice alone survived, and joined her husband at the Savoy, but seems to have slipped into a deep depression soon thereafter.

The means by which her depression was initially treated were quite lavish:

The accounts were kept by my husband so I have no actual knowledge of the outlay entailed. I should, however, assume that for two years or additional expenses due to travel approximated to at least Fifteen Thousand Dollars a year, in excess of our normal expenditure while living in England, or a total of $30,000.00. In addition I had a masseur in attendance from May to October of 1915, at $4 a day for services and $3 a day living expenses, or a total of $1,250.00. Also an attendant for one year at $600.00 and living expenses of $300.00 or more. Our expenses at Monte Carlo at the Windsor Hotel were, according to my best information, $50 a day or approximately $6,250.00. All of these expenses are fairly attributable to the accident and my collapsed nervous condition.

However, A.S. Witherbee began to run short of funds. The following letter reveals a great deal about Beatrice’s collapse, the demise of her marriage and the unfortunate character of her husband:

Hon. Robert Lansing,

June 20, 1916

Secretary of State, Washington D.C.

Dear Sir: In June 1912, after taking stock of my holdings in Mexico, which represented the labor of years, I considered myself to be a comfortably rich man and my future assured. In 1916 I find myself ruined, and regret to say that it has been brought about by “Watchful Waiting.” I am only one of thousands of Americans similarly afflicted by this same germ.

In 1915, my little family of three went down, as you are aware, on the ‘Lusitania’ when that ship was torpedoed and sunk by the Germans. My boy, a child not quite four years of age, and his grandmother, lost their lives, and his Mother, a young woman only then 23 years of age, has been hovering between death and a mad house ever since, a physical and mental wreck. She is even now in a nursing home in London, while I am over here in an effort to get our government to force a settlement of my claim for indemnity for such financial loss as it is known I suffered when the “Lusitania” was sunk.

What money I have left as the result of “Watchful Waiting” has been spent trying to save her. I have braved the dangers of crossing the Atlantic twice, to try and get a settlement, the first time in December last, and the second now. I have been received politely at the State Department, and even had three minutes conversation with you, but I have each time been passed along to someone else, and so successfully that when I was finished with the last gentleman I interviewed, I found myself on the grounds adjacent to the State Department with nothing accomplished.

I have spent thousands of dollars in my efforts to save Mrs. Witherbee, particularly in consultations with leading specialists and in travel through the south of France and in Italy, but I can go no further for lack of the funds necessary, which in itself is another tragedy as she was just beginning to improve a little, and I was encouraged. It has been since I left her last month that she has been taken to the nursing home, which fact alone has increased tenfold my anxiety regarding her. I found that Italy, and especially Rome, helped her amazingly, and I am anxious to take her there permanently. As my finances are now such as to make this impossible without help, I want to ask of the President and yourself an appointment as Consular Agent in Rome. I know that for the moment there is a vacancy through the death of the former Consul, his death having occurred while we were in Rome.

I have no desire to embarrass our government by any undue interference in any policy or plans it may have in disposing of the “Lusitania” matter, but if I must wait, it is only fair that I should find a willing hand, somewhere, that will help me bide my time until a settlement has been effected. I am as competent as any I have seen filling such positions abroad, and by birth and education am a gentleman. I have been a life long Democrat, if that makes any difference, and am fully entitled to the utmost consideration from the President and yourself.

Summed up in as few words as possible, I wish to call your attention to the desperate state of affairs, which have been brought through no fault of my own. I must do something very quickly, as I cannot remain long away from Mrs. Witherbee, especially as she is now absolutely in the hands of strangers.

Awaiting your pleasure, I am,

Very Respectfully, your obedient servant,

A.S. Witherbee

This missive was written on letterhead from the New Willard, which was Washington’s most elegant, and costly, hotel in 1916. Mr. Witherbee evidently was not one to cut back, despite his claims of abject poverty,

It is not clear how long Beatrice remained in the London nursing facility, but at some point news of her situation reached Rita Jolivet, who moved her from the nursing home to the Jolivet family mansion in Kew. She remained there for over a year. She divorced Alfred Witherbee in Philadelphia, in 1919, on the grounds of desertion. She married Alfred Jolivet, Rita’s brother, late in the same year and gave birth to her second child, Lawrence, in 1920. Lawrence would tell Mike, over 80 years later, of how his mother refused to speak of her Lusitania experiences. She was a cheerful woman, and kept whatever memories tormented her in 1915-1919 well in the past. “Awww, you don’t want to hear about that” was the extent to which she was willing to discuss the disaster, and she never once deviated from that course.

Lawrence Jolivet once found a photo of A.S. Witherbee, Junior, and was told, “He was your half brother. He drowned.” Beatrice did not expand upon the story beyond that.

We uncovered a cache of correspondence between Beatrice’s lawyers, discussing her claim against Germany. Amusing from the perspective of 2004, her lawyers spoke of how frustrating a client she was. They suspected, as early as 1923, by her sometimes-hysterical refusal to answer even the simplest questions, that she was not physically capable of recalling the events of May 7th.

Beatrice Jolivet developed inner contentment over the years, and that was all that mattered to her. Her son recalled that she had a “beautiful voice” and was always humming. The Jolivets led a sedate, formal, upper class English life. Their son related that during the 1920s they dressed in the most up- to- date fashions and enjoyed going out dancing; they were refined but not dull. They kept in contact with Rita, although her flamboyant nature sometimes irritated them. They traveled by ship, once aboard the Annie Johnson on the anniversary of the Lusitania disaster. Lawrence Jolivet opined that the significance of the date most likely didn’t register with his mother, for she had put the disaster far out of her mind.

Beatrice Jolivet died on December 16, 1977 without ever having told her family what happened to her as the Lusitania sank. Only one small clue remains: Pauline Jolivet, her mother in law, once revealed that Beatrice had confided to her that she had tried to hold onto Alfred Scott Witherbee Jr. in the water.

(Rev Judy Hill/Mike Poirier collection)

We have often affectionately stated that Beatrice has held her secrets well. The discovery of her legal papers was, we were certain, going to answer all questions. Hundreds of pages later, after discovering notes about her reluctance to discuss the disaster that had passed between her own lawyers, the questions remained unanswered. A creeping mildew stain on the 1900 census rendered exactly two entries on one page partially illegible: May Brown and Beatrice Brown of New York City. When May Brown’s passport application arrived in Mike‘s mail, the 1915 photo of this most elusive of victims was gone, and a note reading that the photo had been removed by family request for copying purposes was appended. The photo, obviously, had never been returned. Beatrice told her family that she graduated from a Sacred Heart School along the Hudson River in New York. There are numerous academies by that name in the region, and none with whom Mike checked had a record of Miss Beatrice Brown. The whereabouts of her formal portrait, commissioned by A.S. Witherbee, are unknown. A reference by Witherbee’s daughter, in a 1930s letter, to Beatrice having been an actress when she and Mr. Witherbee met, proved to be another blind alley.

A month after the disaster, a boy’s body was found drifting off of Kinsale, and recovered. His face was unrecognizable, but he wore a blue shirt, blue flannelette trousers, brown button boots, a round sailor’s cap with a ribbon marked “New York” between two flags, and a grey plaid coat.

Charlotte Luck’s widower and A.S. Witherbee each believed the child to be his son. The matter was decided in favor of the Witherbees, after the clothing recovered from the body was shipped to London, where Alfred, and perhaps Beatrice, positively identified it as being their son’s. This identification was, at best, tentative and certain details of the body do not match the known details of A.S. Witherbee, Junior’s appearance The body had dark hair while the Witherbee child was fair. The estimated age of the body was closer to that of the Luck children than it was to A.S. Witherbee’s age. Unidentified body #185, another young boy, was recovered in a similar outfit and was estimated to be about the same age as Alfred, Junior.

#185. Boy, 3 or 4 years, fair complexion, fair hair. Wore blue suit knickers of serge check, striped vest with 4 pearl buttons, 2 white underflannel vests and drawers, 2 common safety pins in front vest, toe-cap boots, 7 buttons, and white wooly collarette round neck. Property. “Lusitania” brooch badge.

#244 Male child between 5 and 6 years, not recognizable, dark hair, white woolen jersey, blue jersey with turned down collar, blue flanellette trousers, brown buttoned boots and brown stockings, round sailor’s cap, ribbon marked “New York” between two American flags, gray plaid coat.

#244 was recovered at the same time as the body of a male adult, possibly a fireman. The above description came from a preliminary draft of the Confidential Report recovered bodies list, and contains the hand written note “Clothes @Qtown for inspection. Bodies in very bad condition.”

A.S. Witherbee applied for a passport in 1919, stating for the record that he wished to travel abroad to exhume his son’s body and bring it back to the United States. The details on why the exhumation never came about have been lost; A.S. Witherbee junior remains buried in Cobh.

Alfred Scott Witherbee, junior, body #244, was buried literally at the foot of the grave of a man and woman who might have ended up his aunt and uncle through marriage, had things gone differently.

Inez Jolivet, Rita Jolivet’s older sister, was born in New York in approximately 1883/1884. Her age, like those of her mother and sister, was flexible depending on circumstances, but a favorable review of her first public performance, in 1900, stated that she was 16 and was likely accurate.

Miss Jolivet was a classical violinist. Her career highlights included performances in London, St. Petersburg, Vienna, and at the Metropolitan Opera House in New York City. She married George Butler in 1903. She became friends with Nicholas II of Russia’s brother, Michael, and maintained contact with him in both Russia and the U.K., to which he was banished after his 1912 marriage.

George Butler was a rather mysterious figure. He sang professionally under the name of George Vernon and, after his death, he would be referred to as a banker, although in fact he was not. A copy of his birth certificate found among the papers preserved in his case file show him to have been a decade older than he claimed. A list of his business interests, included in one of Inez Butler’s obituaries, showed a portfolio that ranged from gramophone record production to cigarette vending machines. He was vaguely described as being an importer’s agent, and a promoter.

The couple lived on West Eleventh Street, half a block off Fifth Avenue, in New York City. Their home was in a discreetly elegant building that stood in marked contrast to the exuberant beaux-arts style building at Fifth Avenue, on the corner of East Eleventh, where Rita Jolivet lived.

Inez gave her final known public performance, in Russia, in early 1915. She did not return to New York but, instead, stayed at her parents’ home in Kew, England.

George Butler was then working as an arms merchant; selling $3,000,000.00 worth of rifles to Russia at the command of Michael Romanov, Inez’s friend. Newspaper accounts later claimed that she engineered the deal. His presence aboard the Lusitania was related to his arms transactions.

A number of survivors, including Rita Jolivet, remembered George from various points on the final voyage. Butler was at the party Frohman threw on May 6, and he reminded the Broadway producer of his plan to present plays onboard the Lusitania‘s sister ship, Mauretania. Frohman responded “Yes, I did dream of a mid-Atlantic theater, but my leading lady succumbed to mal de mer.” George Butler was with Rita Jolivet and their friends for the duration of the disaster, and was washed overboard with the rest of the party as the Lusitania sank.

Dr. James Houghton later recalled that George Butler was atop a swamped collapsible, but lost his reason and fell overboard, not to be recovered. “I saw a man named Vernon go crazy. He drowned himself before he could be restrained.” Inez would later tell a variant of that story in an interview. George Butler was recovered, body #201, and was buried in Queenstown under his professional name of George Vernon.

Inez Jolivet Butler sent a telegram to George’s family, in Worcester, Massachusetts, telling them of his loss, and saying, “God’s will be done. I am heartbroken.” She made herself available for interviews in London, before returning to the United States, aboard the St. Paul, in June. She spent the remainder of June closing up her apartment, and was said to have been in good spirits, although she was later quoted as saying, “I have nothing to live for” and “my life is over” while despondent. She booked passage aboard the St. Louis, and made plans to return to her parents’ home in Kew.

Inez Vernon spent the week prior to her expected departure shopping in Manhattan, and visiting with friends at a suburban estate in New Jersey. They described her as being in reasonably good spirits. She returned to New York City on July 22, 1915.

Inez’s friends believed that she departed for England as scheduled. The superintendent of her building opened her apartment for final inspection by its new tenants on July 27th. They found Inez, dead, in the master bedroom. She had shot herself, most likely on the 22nd. She was wearing a black evening gown and jewelry, and was kneeling at her bed in a prayer position, with her elbows on the mattress and her face buried in her hands. She was shot through the temple, and the gun was on the floor, under her clothing. A “bad news” telegram she received from someone named Paul on the day she returned to New York City was made available to the press. The telegram was not quoted from directly, leaving its connection to her suicide, if any, still mysterious.

Inez’s decomposed body was soon cremated. Rita Jolivet had her sister’s cremains brought to Queenstown and interred with George’s body after the war. They share a single stone reading: IN TENDER MEMORY OF INEZ AND GEORGE LEY VERNON BOTH YOUNG, BEAUTIFUL, AND GIFTED VICTIMS OF THE LUSITANIA CRIME MAY 7, 1915

The final act of the drama of George and Inez Jolivet Butler came in early 1917, when the Romanov Government, on the brink of collapse, paid the $300,000.00 commission for the 1915 rifle deal into Inez’s estate.

Fortune Came After Death

$47 Estate of Lusitania Victim Grows to $310,621.

George Ley Pierce Vernon, a professional musician who turned his attention to obtaining war contracts soon after the European war began because of the acquaintance of his wife, Inez H. Vernon, with influential persons in England, left an estate of only $47 when he perished on the Lusitania on May 7, 1915. At that time he was negotiating a rifle contract with the Russian government and was on his way to complete the details.

His wife carried on his work after his death, and on July 19th of that year committed suicide through grief over her husband’s death. Before she killed herself, the Grand Duke Michael of Russia, largely as the result of her efforts, approved the contract arranged by her husband, and his estate collected $310,621 commissions on the sale of 259,320 rifles.

~New York Times

Francis Bertram Jenkins, Josephine Brandell’s onboard friend, never recovered from his Lusitania ordeal. He suffered from nightmares and insomnia, and had violent seizures which, from the perspective of 2009, sound like severe panic attacks from their limited description in the press. He continued traveling abroad on business, but his mental state worsened. His final arrival in the U.S., via Ellis Island in 1921, saw him described as an “epileptic.”

He and his family bought a large Victorian style country home in rural Brewster, New York, where it was hoped that the quiet would “restore his balance.” Instead, while doing some early spring gardening with his teenage daughter, Josephine, he contracted pneumonia and died at home, on March 18, 1922, after an illness of a week’s duration.

(Mike Poirier collection)

Frederick John Milford is another sad example of someone who could not overcome the memory of his experiences in the Lusitania tragedy.

Milford worked for the Metropolitan Life Insurance Company in Hancock, Michigan. He boarded the Lusitania planning to visit his father in Cornwall, England. His wife, Ethel, remained at home:

I was having lunch when I heard a dull crash, but it did not startle me at all. Very soon afterwards I heard women screaming, and then hurriedly made my way to the deck. The vessel in a short time began to list to starboard, and nearly a score of the boats on the port side were filled with passengers, but it was found impossible to lower them owing to that side of the ship standing so high above the water.

I managed to get across to starboard. The ship’s deck was then level with the sea. I made for a boat which was just putting off, and, in fact, had one foot on the craft and the other on the ship. Then, owing to something wrong, the lifeboat jammed, and all the occupants were thrown into the water. It was a terrible moment. The passengers in the boat, including women, screamed in terror and soon sank.

Other boats collapsed or turned over, and hundreds of men, women and children were struggling hopelessly about, some frantically clinging to boats which had been upset. I struck out and managed, after swimming for about fifteen minutes to come across a boat in which I was dragged. Hundreds of people were on rafts, and the sea was alive with men and women.

The Flying Fish found Milford’s boat, and its passengers were taken to Queenstown. He was photographed by the press in a group shot that has appeared in many books and articles, and is one of the best known Lusitania photos. He is shown with Mr. Collis, Mrs. Wolfenden, Mrs. Plank, and the Lohdens.

Milford booked passage on the Philadelphia, following his visit to Cornwall. He arrived in New York on June 2, 1915. He returned to work immediately, but could not put the disaster behind him. He was constantly in and out of sanitariums over the next few years, being treated for his nerves. He developed diabetes, which he blamed on his Lusitania injuries.

There was one bright spot in his life; His wife, Ethel, gave birth to a daughter, Marion around 1921.

Milford filed a claim against Germany for $25,000.00, only $281 of which was for lost possessions. The balance was, presumably, for medical expenses and lost time. Edwin Parker, of The Mixed Claims Commission determined that $11,500 would be fair compensation and rendered his decision on January 7, 1925. Fred Milford died on January 5, 1927 at age 47.

|

| Percy Rogers (Michael Poirier) |

|

| Percy Rogers Cabin (D-44) (Paul Latimer) |

Percy Rogers, assistant manager of the Canadian National Exhibition in Toronto, traveled to Europe to obtain “war souvenirs” for display at the Exhibition. He was a last minute booking, filling in for his boss, Dr. Orr, who was unable to travel.

Rogers’ account of the voyage parallels most of the others: pleasant and uneventful, but with an increasing awareness of the war as the trip progressed and Europe drew closer:

Everything went well till Friday morning. Submarines were the source of much conversation but were not regarded with any seriousness as opinions were frequently expressed that a boat with the speed of the Lusitania was more than equal to any submarines. Nobody was therefore disturbed with the thought of being torpedoed. Early Friday morning we sighted the Irish coast and entered into a slight fog. Speed was reduced, but we soon came into clear atmosphere and the pace of the boat was increased.

Rogers finished the final lunch in the dining saloon early:

I immediately proceeded to my stateroom, which was close to the dining room to get a letter which I had written. While there I heard a tremendous thud. Passengers hastened to the boat deck above. Lifeboats were hanging out, having been placed in that position on the previous day. The Lusitania soon began to list badly, with the result that the side on which I and several others were standing went up as the other side dropped…the first lifeboat which was lowered with people at the spot where I stood smacked upon the water, and as it did so the stern of the lifeboat seemed to part and people were thrown into the sea. We heard someone say ‘get out of the boats; there is no danger’ and some people actually did, but this direction was not generally acted upon.I entered a boat in which I should say there were between 20 and 25 women and children, and also some men. Our position was the last boat but one from the stern of the ship. We dropped into the water and for a few minutes we were alright. Then the liner went over. We were not far from her. Whatever the cause may have been, perhaps the effect of the suction, we were thrown into the sea. Some occupants were wearing lifebelts. I was not. (Given this description, which matches several other accounts, it appears that Rogers was in boat #14.)

It is harrowing to think of the men, women and children struggling in the water. I had the presence of mind to swim away from the ship and towards a collapsible boat…for this purpose I had to swim quite a distance. This boat began rocking. Every moment it seemed as if we should be thrown into the sea. I saw George Copping clinging to a rope, almost exhausted…’My wife is gone and I can’t hold out much longer’ were his last words.

Rogers left the imperiled collapsible, reentering the water to swim to a floating cupboard:

People around me were drowning. I remember seeing a young girl with a lifebelt on calling ‘mamma,’ but she was not saved. I had seen her on the liner before and noticed her sister on a collapsible boat. I saw a cupboard, towards which I swam and managed to support myself until I saw a boat. I shouted and was taken on board, and from there was transferred to a trawler.

Eventually we were placed on the Flying Fish and reached Queenstown about half past ten. I was soaking wet, and went into a small hotel where a lady was kind enough to give me a pair of pajamas and socks. In the morning I went into a clothing store and purchased a suit. All my belongings were lost.

Rogers survived physically uninjured, but like many other survivors suffered from “nerves” in the years following the disaster. He returned to Canada, via New York, aboard the St. Paul during the summer of 1915. He carried with him, amongst other exhibits for the exhibition, a model of the U-20 type of submarine and replica of the torpedo that destroyed the Lusitania. However, he was unable to carry out his duties at the Exhibition and was forced to resign.

He suffered a “general breakup,” and required sporadic medical attention for his condition. An attack of appendicitis was blamed, by him at least, on his having been pulled over the side of a lifeboat. The Canadian Courts disbelieved that claim, but allowed him a settlement of $6,500.00 for injury and loss of earning power, and $513.75 for lost personal effects. He died at age 98, on October 5, 1967. He was predeceased by his wife, Ida and survived by two of his four children.

An emotional blow of a different sort struck the widow of Edwin Friend.

Friend, by nature of his relationship with Theodate Pope and his appearance in her oft-quoted letter account, remains a high profile victim, but the depressing final act of his story is little remembered.

Edwin Friend was a Harvard graduate, who worked as a lecturer at both Harvard and Princeton. He was also a devotee of spiritualism, serving as the secretary of the American Society of Psychical research, and it was this interest that brought him, together with Miss Pope, aboard the Lusitania.

Miss Pope and Mr. Friend’s experiences aboard the Lusitania as she sank have been documented exhaustively elsewhere. The two remained together for the duration, along with Theodate’s maid, Emily Robinson, and when it came time to jump, Edwin went first and smiled “encouragingly” upon coming to the surface. Theodate jumped seconds later and was washed into the submerging promenade deck. She survived, against all odds, while Mr. Friend, who got clear of the ship, did not.

Edwin Friend

(Harvard University Archives: Call # HUD 308.04.5)

Marjorie Friend, Edwin’s wife, was pregnant at the time of her husband’s death. Theodate and her mother interceded, and gave the young widow financial support and a place to stay during the late stages of her pregnancy. They soon came to regret their generosity, as they were extremely disturbed by the fast social life Mrs. Friend seemed to be leading.

Marjorie and Edwin’s only child, a daughter named Faith, was born “mentally defective” on September 22, 1915. Marjorie blamed this turn of events on the stress she had endured after the disaster and filed a claim against Germany. The Mixed Claims Commission awarded a sum of $10,000.00 to Faith, in trust of her mother, to be used to maintain the child in the Massachusetts School for the Feeble Minded, where she had long been a patient.

The Gardner family embarked on the Lusitania as the first stage of a trip that would bring them most of the way around the world. James Andrew and Annie Gardner, and their three sons, had lived in North America for several years. They were returning to Nelson, New Zealand, where they planned on establishing a market garden. Their eldest son, Leonard, had traveled to New Zealand in advance, and James, Annie, Eric Clarence, and William Gerard, sailed aboard the Lusitania to join him.

The Gardner Family.

Courtesy of Alison Glenie

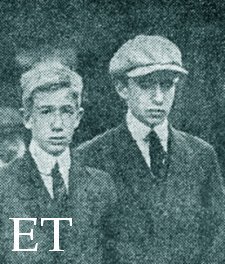

James and Annie Gardner died on May 7th. According to Eric Gardner, Annie fainted when the ship was torpedoed and could not be revived, and she and her husband were pulled down with the Lusitania when it sank. Annie may well have been the fainting woman whom Archie Donald helped carry from the second class dining saloon. Eric and William survived, with Eric swimming to an upturned lifeboat, across the bottom of which he found his father, dead.

The brothers stayed in a hotel near Euston Station, London, before resuming their journey to New Zealand. Eric enlisted in the army during the summer of 1916, joined the New Zealand Expeditionary Force, 3rd Battalion, and was shot through the head and killed in the Paeschendale Offensive on October 15th, 1917. He is buried in the Nine Elms Cemetery in Flanders.

Willie and Eric Gardner

Daily Sketch

Jim Kalafus collection

William suffered from epilepsy after the disaster and was institutionalized for 40 years. He returned to live with his older brother in the Nelson area when he was properly diagnosed and advances in treatment were made,. Willie went on to live a productive, normal, life and passed away on December 20, 1984.