The Lusitania : Part 2 : Three Narratives

Each May marks the anniversary of one of the 20th century’s most notorious events; the sinking, by torpedo, of Cunard Line’s Lusitania off the coast of Ireland with the loss of 1198 lives. While she lived, Lusitania was known as one of a pair of outstandingly beautiful record breakers, and after her death she became best known as a symbol. First of brutality or duplicity, depending upon which side of the fence one stood, and, more recently, of intrigue, conspiracy and governmental wrongdoing. The human element of this most horrible of events has been largely overshadowed.

We have grouped stories with common themes together, which, we hope, will help newcomers to the Lusitania better understand the human aspect of the events of May 7, 1915. The unifying theme of the accounts, we feel, is the incredible waste that the destruction of the ship represented.

The death of Barbara Anderson McDermott, on April 12, 2008, marked the moment when the Lusitania disaster died as well. With her went the last first person memories of a seminal event in twentieth century warfare; upon her passing, the disaster became archival, rather than living, history.

Mrs. McDermott, “Barbara to my friends,” was as nice a lady as one is ever likely to meet. We regret that she did not live to see this work completed, for she took an active interest in the two older articles from which it germinated; but more than that, we regret losing a loyal friend who never missed an opportunity to say or do something nice, if she could, and whose door was always open to us.

We’ve opted to keep the portions of the article pertaining to Barbara in the present tense, and not change “is” to “was.” A tribute, if you will, to a truly lovely spirit who will continue to be a living presence for as long as anyone who knew her remains.

We begin with three first person narratives, given by second class passengers, which give an excellent overview of what happened between 2:10 and midnight that day.

William Uno Mereheina, 26, a racecar driver and General Motors Export representative, was en route to South Africa in May 1915. Meriheina was articulate, and gifted with excellent powers of recall, and his account of the disaster is historically important, and readable.

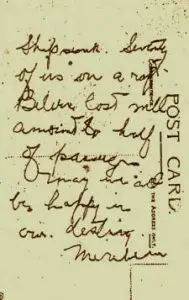

Mr. Meriheina saved a diary-style letter, composed during the crossing; one of several known to exist. However, his notes written on Lusitania postcards while he drifted atop an overturned collapsible are the only known on the spot reporting of the disaster.

The diary letter he wrote for his wife, Essie, reads:

The Lusitania-Saturday. On way out of New York Harbor, and everything is O.K. At Ambrose Lightship we pass the British man of war, Bristol; then sight the British converted cruiser Caronia. We stop, and a boat load of “Tommy Atkins” come on board, presumably for mail and exchanges of messages. No wireless is used. Received wireless from General Motors Company. When I say that no wireless is used, I mean that we receive messages but can’t send any. Later in the afternoon we passed the American Line steamship New York, also bound for Liverpool. Then we sighted a French battle cruiser of the super-dreadnought type, and this cruiser turned and followed us, but gradually was left behind. We are making about twenty-five miles an hour.

Had a grand lunch and dinner. What delayed us on our start was the fact that the Anchor Line sent up about three hundred passengers that were booked to go on board one of their ships, and at the last minute the ship was called out of passenger service, presumably for transport purposes. Feel fine, and am going to sleep well.

Sunday- Woke up, had a dandy salt water bath. Enjoyed a grand breakfast. Sunday services were held on board. Foggy day and quite rough ocean. At noon Sunday our log recorded 453 miles, or half way to Newfoundland Grand Banks. Day passed with concerts in the drawing room. Plenty of seasickness on board, but I feel splendid. Lunch and supper fine. Because of rough weather, nearly every one turned in quite early. At midnight I understand we passed a British cruiser. I noticed a great deal of light signaling going on. Evidently we are being carefully convoyed all the way across. Still, no ships are in sight for any length of time. We have passed quite a few vessels bound both ways. Owing to our great speed we don’t stay in sight of any one ship very long.

Monday- Feeling great. Fog is prevalent. Dandy meals- passed a bunch of ships. We had a concert, games, races and drive whist, and various other entertainments.

Rolling quite a little, but am not effected in the slightest. Have an M.D. – surgeon- as room mate. We have become quite good friends. He is going to offer his services to the Allies as surgeon. He is Dr. D.V. Moore. He is well educated and proves a good, companionable, room mate.

Several of the passengers are grand singers and players, and they keep every one interested. I am studying my work and think my trip will do me good.

Tuesday-resumption of games on deck today. Dandy sunshine weather- feel fine.

Meriheina composed a second letter, ashore, on May 8th, at the Queen’s Hotel in Queenstown:

We were eating lunch at the time when suddenly, with absolutelyno warning, we felt a heavy explosion up forward, near the first cabin section; a grinding and ripping. The boat immediately lurched toward the side that you were looking at as we were tied to the New York dock. She settled so much that dishes fell off tables and it was difficult to walk the aisle between tables. There was little panic- individuals moaned and cried, and just a suggestion of a rush for exits.

About five seconds after the first crash a second one came along, with the same sinking sensation on the one side. The men did a great deal for the women and children, but remember, the boat sank to the bottom in less than twenty minutes.

The lifeboats that were lowered were either overturned or smashed against the side of the boat, dumping the human loads into the ocean. I don’t pretend to describe the total scene; it was too horrible, but I did everything I could to help the women off. I placed a lifebelt on myself and placed several elderly women in life rafts that might tear loose from the decks when the boat sank, which they finally did.

The people who reached the decks were the only ones saved, as the ship sank in a flash when she finally started nose downward. On sinking, her boilers blew up and deck roofs blew off. I had faith in the boat not sinking and therefore remained on the back bridge ‘til I was washed off.

The internal pressure created in the hull by the inrush of water was sufficient to blow out port hole plates, and the air shot out of these like steam. I saw many bodies floating away deep in the water. Just before the final plunge the back of the hull lifted away up out of the water, revealing to me the propellers and bottom of the hull. At this time I was probably 175 feet above the surface of the water. All the time up to the last second several other fellows and myself were loosing the rafts, so that they would float and not be carried down with the hull. Our labor was for naught, as only a couple of the rafts tore loose, and in doing so smashed themselves to pieces, anyway.

The sight of the people falling overboard and sinking, with apparently no effort to swim, was maddening. Well, when the final plunge came I believe that I was the last, or one of the very last, to get off. And I tried to jump, but got fouled with the angle of the deck and the rail posts and was washed off, only to be slammed back downward with the hull. I lost consciousness and then I came to with the bright sun shining in my eyes.

It was cold, and I felt stunned, but I struck out for an overturned lifeboat that was about a city block away. There were people all around, both live and drowned. On reaching the boat I hung on to the side by the rope for a minute or so, when a man, grabbing my neck, placed his arm over my shoulders and pulled me off. I turned and hit him. He weighed over two hundred pounds, and I could not shake him off, so I sank purposefully and he let go at once. I again reached the boat and the man also had a finger grip on the rope. Several others were hanging on.

One after another, we managed to climb up on the slippery sides and lie on the keel. I finally reached out and helped this particular man up on the boat, and several others. We finally had about twenty men and women on the overturned lifeboat and she threatened to sink, when another overturned boat came near and some of the men made for it. We kept these two overturned boats together, loaded with humans half dead and some dead.

Then a broken raft was forced near us, and we placed all of the women and children thereon. Right near us was an upright lifeboat, but entirely submerged so that only the oar locks were visible at times. This boat contained about a half dozen women and twenty men. We finally got the women off of her on the raft, and the men remained, several drowning within.

We had a lot of trouble with our crew of these two overturned lifeboats and one upright lifeboat and one raft- the crew I mean were the people thereon. Some wanted to paddle to shore, which looked twenty miles off, and others wanted to save their strength. We sang “Tipperary” a couple of times (sacrilege) and then, due to the women’s crying and begging us to stops, we sang “Lead Kindly Light.”

All this time we could see other lifeboats at a distance, either upturned or straight, but all loaded to the water’s edge. Only about ten boats were afloat, and more than half were overturned and the rest were broken or half submerged. I did not see one good lifeboat afloat.

I counted the boats and estimated their inmates as nearly 500. We had nearly one thousand nine hundred altogether. By the way, sing “Tipperary” and think you are adrift on the ocean with death everywhere in evidence.

Then after more than three and one half hours, the fleet from Queenstown came into view. They picked most of the other boats first as we were farthest away, and then came to us. All this time we were constantly adding to our crew, and sinking deeper and deeper. In the three and one half hours agony I found time to take out my fountain pen, which I still had, and dug out a couple of wet postcards from the drawing room of the boat. I wrote my impression very mildly on two of them. The rest of my time was taken up either pumping arms up and down or squeezing some poor “half-gone’s” wet clothing. We finally had more than seventy on our improvised combination raft consisting of raft, overturned and submerged boats

Then they picked us up. The Indian Empire was our rescue boat. We were landed in Queenstown at half past nine, about seven and one half hours after taking to water.

Then they picked us up. The Indian Empire was our rescue boat. We were landed in Queenstown at half past nine, about seven and one half hours after taking to water.

Meriheina’s two postcards read:

Ship sunk. Seventy of us on a raft. Believe lost will amount to half of passengers. May we all be happy in our destiny.

And

Steamship coming; also sail boats. Hope most of us will be saved. May they be glorified with a crown of life and death. Hope the lives of the lost ones will pay the score.

Nellie Huston, 31, was returning to England after spending nearly a year in Chicago, Illinois. Miss Huston died May 7th, never to be found, like hundreds of other passengers.

A woman’s handbag was later recovered from the debris drift, and in it was a four page, incomplete, unsigned diary letter detailing the events of the final crossing. Excerpts from it were published, and from names mentioned in the text, Nellie Huston’s parents were able to identify their daughter as the author.

The letter was filled with small talk that, in retrospect, makes it one of the saddest of all Lusitania documents.

By the courtesy of Geoff Whitfield, Miss Huston’s family have generously allowed us to quote the letter in full:

RMS Lusitania

May 1st 1915

My Dear Ruth,

I’m just going to bed and thought I’d start a little letter to you and let you know how I’m getting on. Cold though and it’s a good thing I had my heavy coat. I’ve met some awfully nice girls and we’ve been toddling around all day.

We were late starting this morning because we took passengers off a boat called the “Cameronian” so I can tell you we are feeling crowded. I’ve got the first sitting for meals so I’ll have to be up at 7am breakfast at 7.30.

My! The mail I got today. The steward who was giving it out was amused. He said it might be my birthday.

I do hope the bouquet came out alright. Just don’t get yourself tired out with sewing again – you are certainly a monkey. How did you make that waist? – – something about making it but it doesn’t look possible to me. I’m going to try it on. I had a pair of silk stockings from Prue and a piece of silk from Aunt Ruth and a rose. I had cards from Nellie Casson, Will Hobson, Tom, Edith Klaas and a nice letter from Lu which I’m going to answer. I had letters from Kate, Mother and Arthur. They weren’t sure if I was really coming on this boat but wrote chancing it. I’d rather have it that way than have them worrying. I’m so surprised to hear that Will and Bee cried, I didn’t think it would worry them. I was so afraid Aunt Ruth would think I was acting funny. ? ? a baby and I do hate to cry like that. I’ve felt like doing it quite a lot since I’ve left.

I had a note from aunt Alice and she seemed pleased because you had been out to see her. They came down to see me off this morning. Tell Charlie that it must have been an awful bang, it must have been done between

your house and the station. I hope it hasn’t smashed the doll’s head in. If so, I think they ought to pay for it.

We have passed 2 cruisers – one was the “Edward VII” I think I’ll write you a little note every day and this will be quite a budget.

Good night.

TUESDAY

I didn’t write a letter each day you will notice. On Saturday night after I’d written to you I went to bed and had a fine night. I’ve got the top bunk and really I don’t know if I was supposed to be able to spring right into it but I tried and couldn’t so had to ring for the steward to bring me some steps. They seem to be short of everything so I had to wait quite a while. He tried to persuade me to jump in but I’m too heavy behind.

I went to Church on Sunday in the 1st saloon, it was awfully nice. The orchestra played for hymns. The writing room was too full on Sunday night for me to write.

It rained most all day Sunday and Monday. We had a jolly whist drive last night and I got 2nd prize. It was a manicure set something like the one I got from Lucy for Christmas. The sun is shining today and it is much pleasanter. I felt rather like being seasick last night but the feeling past off.

WEDNESDAY

Just about half way over. I wonder if the folks will meet me? I’ve made quite a list of friends. The bedroom steward off the “Cameronian” is on this boat and he was surprised to see me. He’s a fine fellow and looks after us fine. I think I’ll do a little sewing today.

THURSDAY

I’ve had a splendid passage up to now. Lots of people have been sick but I haven’t yet. We had a fine concert last night and were up till about 12.30am. We are having another whist drive tonight.

This morning we have all the lifeboats swung out ready for emergencies. It’s awful to think about but I guess there is some danger. We expect some ?? coming to meet us today. What a crowd there are in the boat and all English. I was so pleased to see the Union Jacks on this boat when we were in New York, there are quite a lot of distinguished people in the 1st class but of course you couldn’t touch them with a soft pole! There is a Vanderbilt, one or two bankers. I have made lots of friends

and if it wasn’t for the worry I could say we’ve had a lovely trip.

Henry Needham, recently of New York, was returning to his family home in Sidcup, U.K. when he sank with the Lusitania. His brothers had recently enlisted, and like many of the male passengers, Needham was doing his duty and planned on enlisting upon arrival:

We were two hours late in leaving New York, and we had a bigger passenger list in second cabin than the Lusitania had ever carried before. This was partly due to the fact that one of the boats due to sail that day had been commandeered by the government and had been sent up to Canada for troopship purposes, and all her passengers had been turned over to the Lusitania.

The crossing was a pretty good one for the time of year, though we did not get much sunshine. Just off the Irish coast we ran into a fog, and had to slow down to about half our normal speed. For three hours or so, our foghorns were going, so that any German vessels in the neighborhood had full warning that we were coming along.

The haze lifted, and we had a clear view of the Irish coast, but although our speed was increased it was not so great as it had been earlier, and several of the passengers spoke about it.

We were about half way through lunch when we heard a dull thud. We were some distance from the spot where the boat was struck, so could only hazard a guess at what had happened, though of course the Germans’ threat to torpedo the boat was uppermost in everybody’s mind.

It was just as if she had struck a rock. People at once rose from their seats, women picked up their babies, and quite a wail went ‘round. We tried to reassure them, and I saw the last of my friends at that time.

I proceeded to the main deck. It was impossible to get near the boats to render assistance because of the press, so I climbed on the bridge at the stern of the boat that is used when they are backing out of harbors, and from this spot had a good view of what was happening all the way down the port side of the ship.

She had a heavy list. Men were shouting that the captain had stated that the boat was all right and would not sink, at which there was quite a cheer. I noticed several women with young babies sit down on the deck with a sigh of relief.

The first boat on the davits was full of people when they started lowering her. I have an idea that there were very few of the actual crew assisting with it. She started quietly, suddenly set off with a rush, hit the side of the ship, struck the sea and was reduced to matchwood. I could see the people struggling in the water and gradually being carried away by the current. Some were wearing lifebelts; they looked like corks bobbing among matchwood. The others gradually disappeared.

The second boat also met with disaster. One end broke away as she was part of the way down, and the other was held firmly. Eventually someone cut the rope away, and she dropped into the sea and smashed up. The third or fourth boat to be lowered had one end smashed in. She was full of people, and immediately filled and sank.

By this time the starboard side must have been on a level with the water, and a few minutes later I saw the forepart of the vessel break away. A mass of people was swept into the water.

By this time I thought I better get to the boat deck. I narrowly missed being swept into the sea by a collapsible boat which suddenly swept into the sea with a rush. At this time steam was pouring out of the port holes and the noise was awful.

I merely had to step from the ship into the ocean. When I came to the surface, I saw one of the collapsible boats floating upside down. I managed to swim out to her and a steward who had just clambered on gave me a helping hand. I looked round for the Lusitania, but she had disappeared.

There were perhaps a couple of dozen boats and masses of wreckage within a radius of a mile. People were struggling in the water all round us. Several made for the upturned boat, and we were able to help them on. One woman with a child was none-the-worse for her experience. She had secured a lifebelt. In about a half an hour we had about thirty people on the boat. One little chap had his leg broken and he cried pitifully for his mother.

We picked up a few more people and gradually drifted out of the wreckage. A crowded boat some hundred yards to our right was sinking. They called to us to help them, but it was impossible for us to do anything. All we could do was sit there and watch them sink. The moaning of the people in the water was terrible to hear.

We were wondering if the S.O.S. had been picked up, and began to look around. A steamer was sighted about six miles away heading due south. We cheered our companions in misfortune by telling them she was coming to our aid, but she never altered her course, and it was obvious that she had no wireless on board and from that distance could not see boats low down in the water.

It was about four o’clock when we finally saw boats approaching from the Irish coast- about an hour and a half after I got into the water. We first saw a smoke stack, and then all around we could see steamers coming in a cloud of smoke showing they were putting on every ounce of steam.

Henry Needham returned from his WW1 service, only to become a victim of a second wave of German attacks on civilian targets; dying in an air raid on Sidcup on July 4, 1944.

Mike Poirier

Mike Poirier