The Lusitania : Part 3 : The Survivor

Lusitania survivor Barbara McDermott tells her story.

There are two known Lusitania survivors alive at this writing. (January 2008) Barbara McDermott, a personal friend to us all, appears in several segments narrated in the first person. We have chosen not to use our names in these portions. Cliff Barry, Mike Poirier, Jim Kalafus and Tim Yoder were present, in different combinations, during each of the six get-togethers which went into the creation of her segments. The “I” in the narrative is not any one of us in particular. We wanted to keep this a story about our friend, and not create a vanity project into which we inserted our own names as frequently as possible, with Barbara reduced to co-star. Barbara has said, on occasion, that the only good thing to have come out of the disaster has been the many friendships formed, and many kindnesses show to her over the years, as a direct result of the Lusitania. In that spirit, we would like to dedicate Lest We Forget to her.

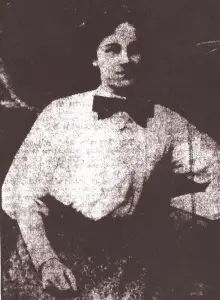

We are sitting at the dining table of Lusitania survivor Barbara Anderson McDermott. Outside, sunlight dances on the surface of a large swimming pool, and from her sun porch can be seen a vista of well-tended gardens and sunny blue skies. It is a beautiful May day not, we have noted, unlike the one 91 years before on which she, and her mother, and nearly two thousand other people saw their lives suddenly reduced to a matter of minutes and luck. Barbara’s mother, Emily Anderson, a true beauty, gazes serenely down on us from a pre-disaster portrait given a place of honor in Barbara’s living room. I cannot help shifting my eyes from the photograph to Barbara to see which of her mother’s features she inherited. I observe that, in repose, mother and daughter both wear the same expression. The resemblance must have been striking when Barbara was in her late 20s. An antique clock, a wedding present, keeps time from a wall hung with pictures of grandchildren, and great grandchildren.

Barbara’s home in Bridgeport, which she left forever in 1915.

The conversation is genial. Three of us have visited Mrs. McDermott before; the fourth member of our group is meeting her for the first time. She shows him a framed photograph, most likely taken on May 8th 1915: Barbara Anderson being held in the arms of Assistant Purser William Harkness, the man who saved her. Harkness is smiling for the camera; Barbara is not. “He died young” she tells her new friend. And so he did, surviving the Lusitania by only 23 years. The photo hangs at eye level behind her dining table, and one cannot miss it. Her new visitor is a cat person, and comments on Barbara’s collection of china and fabric cats. She laughs pleasantly, and they hit it off.

When one visits Mrs. McDermott, “Barbara to my friends,” one leaves well fed. As the five of us converse, Barbara has produced fresh sliced ham and cheese, bread, and side dishes. “Have another sandwich” she urges as we finish our respective seconds. We settle down to discuss new developments in our ongoing Lusitania project. our third sandwiches of the visit. She comments, with interest, on various new discoveries we have made, and mentions a brief fragment of memory that recently came to her, of looking down at men from a height, perhaps from the ship towards the pier before departure.

Barbara is a naturally cheerful person. She is an optimist. But, today, a touch of sadness enters her voice, which is surprising for its rarity.

“My mother was a good person. She was very kind. A good person. I was not with her long, but I do remember her and I’m glad that I can. Because no matter what happened I always knew that she loved me.”

I think of what a remarkable moment this is. Once there were many who could have echoed the same sentiment. Arthur Scott, who lost his mother. The three surviving Mainman children who were orphaned and lost their older brothers as well. The orphaned Gardner boys. Edith Williams. Helen Smith. They are all gone now. The only other remaining survivor was an infant and has no recall of the disaster, or of those she lost that day. The final living link capable of recall is sitting there a few feet away from us, expressing the impact of an awful chain of events that left her stranded, with a dying mother, two thousand miles from home for the duration of the war.

Barbara McDermott and the locket…

I find myself wondering what else is tucked away, beyond conscious recall, in Barbara’s memory. She may have heard Hilda Stones sing, at a performance given in second class the night before the tragedy. Hilda’s voice was described as beautiful. She died the following afternoon. Barbara remembers the moment after the torpedo struck, as the people in the second class dining room began to rise from their tables, but I wonder what else is there, hidden away, that she witnessed. She was in Lifeboat 15, when its occupants pulled Ogden Hammond from the water; did she see the rescue? Did she notice a pretty mother, pregnant, holding another little girl and pleading with a pair of men on the staircase, as she was carried towards the lifeboats? Did she see a handsome young man in a green spring suit calming a hysterical young woman, and leading her towards a companionway to the boat deck? A little girl, perhaps wearing a white dress and hat, searching the crowd for her absent parents? Once thousands of people knew, and loved, those about to die who surged and jostled and cried around Barbara and her mother. And, once more than 750 survivors remained to bear witness to their pathetic final moments. Nearly a century later all of the others capable of recall have gone, leaving Barbara’s fragmentary memories the only living record.

“….no matter what happened I always knew that she loved me.”

Barbara McDermott’s short time in England after the disaster has never been discussed outside of her family and a few close friends,. She speaks of it now because she wants to leave a record that hers has been a happy life. We’ve always been impressed by Barbara. She was two years and eleven months old in May 1915, and her memories are exactly what one would expect a three year old to retain. She has never added “coloring” to her story, and when she is repeating something she was later told about the disaster by her mother or relatives, she says so. There are no improbably elaborate lines of recalled dialogue. No step by step “this is exactly what we did” recreations. And this paucity of detail is what makes Barbara a treasure, because when she speaks we know that we are getting a word picture of an actual memory from that afternoon.

Barbara has recollections of a small room on the Lusitaniawith two beds hanging off a wall, presumably the cabin she shared with her mother. She can remember looking through the railings of the balcony above the second class dining room, on the day of the disaster, and seeing a long table full of men having their lunch. And, she can remember the explosion.

Barbara McDermott

We lived in Bridgeport then, my mother, my father and I. I can remember that before we left, my mother bought me a special dress to wear when we got to England, and I was allowed to wear it once. I can remember the sun shining through the window, and wearing that dress. You know, I wasn’t even three years old yet. But I remember some things. We stood on deck during sailing and I looked back at the dock and there was a large crowd. I looked for my father in that crowd of men, but couldn’t see him. I then remember we left the deck and entered the ship. Our room had two beds in it, one on top of the other on the wall.

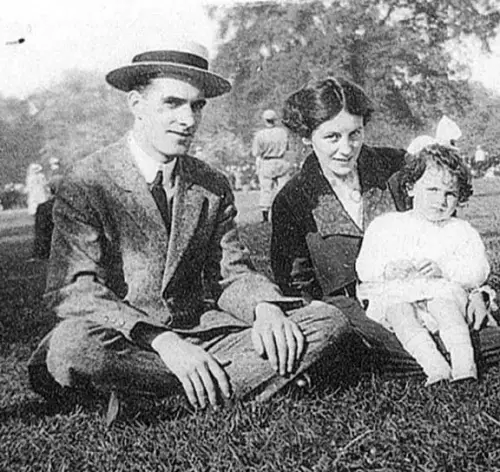

Barbara Anderson with her father and mother

I can remember the dining room. We were seated on the upper level, and that is the only reason I am alive today to tell you about it- because when we were torpedoed my mother was able to take me and walk straight out on deck.

Barbara described their table as very small and that it was just the two of them at the top of the balcony. The table, she said, faced the doorway leading to the corridor. She also said there was a table, with just men seated at it, near theirs.

I got up out of my chair and stood next to my mother, and faced the rail. I could look down and see all those people at the long table talking and eating their lunch. I can remember the noise, the explosion, and looking through the railing at the people in the room beginning to get up from their tables. I can remember being in the lifeboat. People sat facing me. You know, all through it, I held on to my spoon from the dining room. When I got to my grandparents house, I still had that spoon. My grandparents saved it, but when I came back to the United States, I did not take it. I don’t know what became of it.

Barbara does not recall the mechanics of her escape from the ship. She was told by her grandparents, and perhaps by her mother, that Emily and Assistant Purser Harkness, jumped from the ship together, with Harkness holding Barbara. Barbara can remember their arrival in Liverpool, and passing through a yellow tunnel to where her Anderson grandparents and her beloved Aunt Edith waited to meet her.

I remember this most clearly. There was a long yellow tunnel we walked up when the boat got to Liverpool. And our family was waiting for us at the end. After the disaster I went to live with my Pybus grandparents. I don’t think my mother had much to do with my father’s parents. But I do remember spending time with them when my mother was sick.

Barbara Anderson and Emily Anderson

Emily Anderson lived less than two years beyond the disaster. She was pregnant when she and her daughter escaped from the Lusitania, but her child, a son named Frank, died in early 1916. Emily contracted a lung disease, of the sort referred to by the generic terms “consumption” or “a wasting disease,” and although she was brought home, she lived in a wooden house at the back of the Pybus’ garden and Barbara was not allowed to see her.

I did not really see much of my mother as she was very ill when we got back to Darlington; I remember her being in a wooden out house in a bed. I was brought to see her, once, when they knew she was dying. I can remember her holding arms out to me with a beautiful smile on her face. I will never forget that hug or smile. It was Christmas time and she gave me a doll carriage. My mother was a good person. She was very kind. A good person. I was not with her long, but I do remember her and I’m glad that I can. Because no matter what happened I always knew that she loved me.

The doll carriage, Barbara’s final gift from her mother, holds a place of honor in her living room.

Emily Anderson (left) died in 1917; Barbara Anderson, just before she left England, in 1919.

Barbara’s grandparents and extended family tried to make her life as normal and pleasant as possible during the time that Emily lay dying, and gave her a supportive and loving environment after her mother died in early 1917. She recalls her time in England fondly:

I went to Bradgate School in the town center and can remember that our class rooms were divided by green and brown cloth. There were lots of soldiers and the school closed down soon after. There were German prisoners of war in Darlington, and Grandpa Pybus told me once that I was not allowed to speak to the prisoners that walked past my school. When I returned to America my teacher used to ask me to stand up in front of the class and read out loud, I had always been a very good reader. My grandfather Pybus used to take me to school on a horse and cart, he worked for a family in the local area. Once I was with my best friend Eileen and we were chased down a hill by a baby pig. We hid in a cart and we could hear the pig grunting outside – we were giggling. Christmas time was spent between the Pybus and Anderson houses – both were at opposite ends of the town, I clearly remember walking between the two. Once I was walking down a wide street and a man on a bike knocked me over. I ran to my Aunt Edith’s house, I hid under the dining table, she came up from the basement, I told her what happened – I wasn’t hurt, just upset.

Barbara has always maintained that she did not want to leave England. Her father wanted her to return to America, and so she had no choice but to go. Rowland Anderson had remarried, and was in the process of initiating a claim against Germany in the U.S. Mixed Claims Court. Barbara recalls that her grandparents did not want to part with her. She can recollect that her uncle, William Pybus, was fatally injured during the time that the arrangements to send her back to the United States were being made, and her grandparents were upset.

She departed in late December, 1919, aboard the Mauretania. Fellow Lusitania survivors George Walter Bowers- Bartlett, his wife, Irma Florine, and Third Engineer Andrew Cockburn, now Chief Engineer, were also aboard. Barbara clearly remembers sitting at the Captain’s table. She shared a cabin with a “horrible woman” who, on arrival in America, tried to stop her from running to meet her father.

Oh, that woman was horrible! I don’t know where they found her, but I was to share a cabin with her. She was supposed to keep an eye on me until we got to New York. I can remember there was a place where we were able to get off the ship, to walk, before we started across the ocean, and this woman actually went, and went to the bathroom right there in a ditch next to the road. That was the kind of person she was. She said to me “How do you expect to recognize your father when we get to New York?’ You won’t remember him” Now, why would she say something like that? Of course I would recognize my father. I can remember the library, and being able to look out the window and see the ocean. I was seasick, and the Captain found out about it and I was invited to eat as his table. His name was Captain Rostron. When we got to New York, on Christmas Day, they were waiting for me on the pier. And I knew right away who my father was, and that woman tried to hold me back but I ran to him. And they had a doll for me, and they took me home.

Barbara admits that there were adjustment problems at first between her and her stepmother. She got along well with her step-grandfather. Rowland Anderson had left Bridgeport during the war years and settled in East Haven, Connecticut. Barbara remembers her house there fondly. She was educated in a commercial high school, where students were taught job skills along with the standard academic curriculum.

I was given classes in elocution. I am grateful for that. I always loved to read out loud, and the classes improved my diction. Everyone should take elocution classes if they can, because a good speaking voice is very important, and it gives you confidence and gets you over being shy.

Her happiest memories, outside of confidential family stories, are of the years she spent working at Grants, one of the leading department stores in New Haven. She had a boss, Mrs. Champagne, who took the time to mentor her, and who was adept making just the right kind gesture at the right moment. Barbara still speaks of her fondly. A local newspaper ran a profile of Barbara, in which she spoke of her Lusitania experiences, in the 1950s. It was not until after the death of her husband, Milton, that she began extensively discussing the disaster in public. She has appeared at conventions, been interviewed for television and radio, and featured in books.

“It’s funny. For most of my life I’d tell people that I was on the Lusitania, but I could tell that they didn’t believe me.”

I look again at Emily’s portrait. I think for a moment about May 1, 1915. The Andersons most likely took an early commuter train to New York City from Bridgeport, Connecticut. The notorious German Embassy warning about unrestricted submarine warfare appeared for the first time that day, in the morning edition of the daily papers in New York City, and so logic dictates that Emily probably did not learn of the warning until she was already aboard the ship.

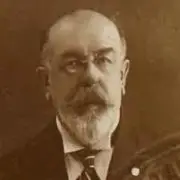

Emily Mary Pybus Anderson

Emily Mary Pybus was born on July 22, 1888, the youngest daughter of Robert and Margaret Pybus of Newton Morrell. Her parents had lost several children in the previous years, and at the time of her birth, there were only two surviving children, William and Margaret. The family moved to Woodside Gardens on the outskirts of Darlington soon after Emily’s birth. Emily began attending Harrowgate Hill School at the age of six, and at ten was presented with a book as a reward for 100% attendance, due diligence, and satisfactory conduct, by Mr. Ivor Hall, Chairman of the Darlington School Board. This book is still in Barbara’s possession. Emily went to work at the fashionable “Parisienne Mantel” haberdashers on High Row in Darlington, at age 14. Barbara has a photo of her mother posed formally with the other shop girls, among who is her sister, Margaret.

Emily became acquainted with Rowland Anderson, a 21 year old student at Darlington Technical College, in early 1909 and the couple soon became engaged. Roland immigrated to the United States, with his brother Percy, in 1910 and began setting up a home for his prospective bride in Derby, Connecticut. Emily followed in early 1911 on the RMS Caronia. Friends of her fiance had been corresponding with Emily prior to her departure for the U.S., and she stayed with a Mr. and Mrs. Morris until she married Rowland in June 1911.

Emily and Rowland’s daughter, Barbara Winifred, was born in Derby on June 12, 1912

Emily decided to return to Darlington, to see her parents, despite the war that was gathering pace in Europe in the spring of 1915. She was five months pregnant, with a baby due some time in September, when she and Barbara boarded the Lusitania together.

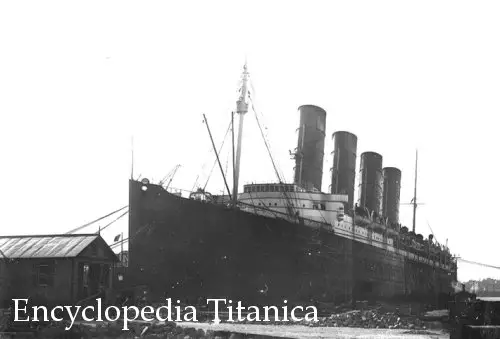

From a negative in the Jim Kalafus Collection

Emily gave an interview to a reporter from the Northern Echo upon her arrival in Darlington. The reporter was evidently quite taken by her, and commented on how hard it was to believe what she had just endured, in light of her beautiful and healthy appearance. Emily described the voyage as ‘splendid.’ She said that only a few of the passengers regarded the submarine threats seriously.

“I was in the saloon at the time and made for the boat deck at once. Someone carried my little daughter up the stairs to the deck or I might not have got there. The deck was at such an angle that we slid down towards the boats. I got into one with the covers on, but I was ordered into another one, (#15) which was ready. There was no panic and the rule of women and children was carried out. There was no need to lower the boats, for they were touching the water. They simply cut away the ropes from the davits”.

Much of Emily’s interview was paraphrased. She described her friend, Mrs. Cox, accidentally dropping her baby, Desmond, on the deck. Minnie Wilson caught the infant when he was thrown into boat 15. Emily said she was afraid that they would go down with the Lusitania as they were so close to the side of the ship. She was also afraid of the funnels, which hung over the lifeboat, but the ship went down quite smoothly. All of this information was imparted, however, in the reporter’s voice and not Emily Anderson’s.

One wishes that Emily had left a more detailed version of her story. Boat 15 effected a last minute escape from the ship. Had Assistant Purser Harkness not found the two, and placed them into the boat, they would probably have been washed from the deck about two minutes later as it submerged. Where had they been before Harkness found them? What had Emily seen? Had she played an active or passive role in trying to save herself or her daughter? We will never know, barring the discovery of one of Emily’s lost letters from May and June 1915.

Emily and her daughter were transferred into another boat, in which two men were bailing. They landed at Queenstown in the evening of May 7th. They were met by Rowland’s parents upon arrival in Liverpool and taken back to Darlington. Emily immediately went to her parents in Woodside Gardens.

Emily gave birth to a son named Frank Rowland, on September 30, 1915. The child became ill and passed away of bronchial pneumonia on March 16, 1916. In that year Emily also lost two of her cousins, who were serving in the Australian Army.

Emily’s health began to decline in 1916. To the trauma of the disaster, the separation from her husband, and the death of her son, was added a respiratory disease. She died on March 11, 1917, at age 28. Barbara has always directly attributed her death to effects of the Lusitania disaster. When Rowland Anderson filed claim against Germany before the Mixed Claims Commission, German lawyers unsuccessfully tried to establish that Emily had been tubercular before the disaster and that, therefore, the disaster was not a contributory factor to her death. They did establish to the satisfaction of the court that Emily died of type D or type E tuberculosis, and not from the effects of prolonged immersion as her doctor in England stated in an affidavit.

Her funeral took place at a nearby cemetery in Darlington, with Emily’s parents and sister, and Rowland Anderson’s family, present. Rowland was unable to attend. Further tragedy struck the Pybus household when Emily’s brother, William, died from wounds in Cologne, Germany on September 14, 1919.

Emily Anderson, and her son, Frank, were buried at church expense. Rowland Anderson listed the cost of burying his wife as one of his grievances, in his claim against Germany but, in fact, he never purchased the plot. The precise location of her grave was forgotten with the passage of time. Barbara was aware that her mother was interred somewhere in Darlington, but did not know in which cemetery.

(Courtesy of Cliff Barry)