The Lusitania : Part 4 : The Families

Only a handful of the Lusitania’s families, and we are expanding the term ‘families’ to include mothers traveling with children, survived intact. Most did not survive at all.

by Jim Kalafus, Michael Poirier, Cliff Barry and Peter Kelly

|

| Cecelia Owens. Courtesy of Carol Keeler |

|

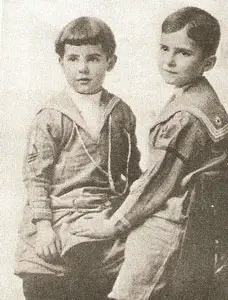

| Ronald and Reginald Owens. Courtesy of Carol Keeler |

|

| Alfred Smith. Courtesy of Carol Keeler |

|

| Cecelia and Hubert Owens. Courtesy of Carol Keeler |

Terrible as certain aspects of Emily Anderson’s story were, she was actually among the more fortunate of the Lusitania mothers. Her daughter survived, she found a place in a lifeboat, and she lost no one that day. Only a handful of the Lusitania’s families, and we are expanding the term ‘families’ to include mothers traveling with children, survived intact. Most did not survive at all. Circumstances that day worked against children, and against easy evacuation of entire families. No war zone precautions were in effect among the passengers. It was not suggested that families stick together, and children were allowed to move about the ship at will. Lunch was in the process of breaking up when the torpedo struck. People had dispersed to enjoy the final beautiful afternoon at sea, and a common thread among the accounts left by parents who survived was the horror of trying to find children, who could have been anywhere, during the liner’s final 18 minutes.

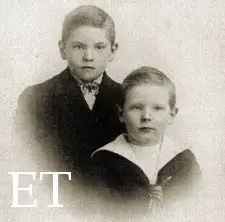

Cecelia “Cissie” Owens, of Ellwood City, Pennsylvania, boarded the Lusitania on May 1, 1915, with her sons Reginald, 10, and Ronald, 6, her brother Alfred Smith, sister-in-law Elizabeth Jones Smith, and niece Helen. The Smiths’ infant is commonly refered to as Elizabeth “Bessie” Smith, but Helen Smith recalled that the baby was a boy named Hubert, and the family monument is inscribed as such. The extended Smith family had immigrated piecemeal to the United States from Swansea, Wales, over the prior ten years. They settled first in Yonkers, New York, and later in the Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania area. That May, two branches of the family were returning to the United Kingdom. It was said that the Alfred Smith family had grown disillusioned with American life and were permanently resettling in Wales. Newspaper articles claimed that Cecelia Owens and her sons were simply returning to her ancestral home for a visit.

The afternoon of May 7th found Cecelia minding the Smiths’ infant in her cabin, while Reginald and Ronald Owens played on deck with their cousin Helen. Shortly after two, the boys appeared at the door to request an extension of their play time. Cecelia would later recall their last words as being

She granted them permission for another half hour on deck.

Cecelia interpreted the initial blast as being the ship running aground or perhaps striking a rock, but there was no mistaking the second stronger explosion for anything other than what it was. Joining a crowd of ‘scampering’ passengers, and carrying Hubert Smith, she climbed upward to the open second class decks hoping to find her sons. She encountered, instead, her brother and sister-in-law, who were searching for their missing daughters. Cecelia returned Hubert to them, and then the Smith family and Mrs. Owens parted, each setting off separately to find the missing children.

Cecelia moved around the deck calling for her boys and Helen. A stranger stopped her and affixed a lifebelt at some point, and after that Mrs. Owens was tossed into a lifeboat. It capsized, and she was thrown into the ocean along with the other occupants. Cecelia swam with two men to a swamped collapsible, from which a fishing trawler rescued her some hours later.

Reginald and Ronald Owens died in the disaster, as did Alfred and Elizabeth Smith and their infant. None of the bodies were ever recovered or, if recovered, identified. Cecelia’s only consolation came when she was reunited with Helen Smith at her hotel in Queenstown. Helen saw her at a distance and called out “Why, here is auntie!”

Mrs. Owens traveled on to Swansea, where she was described as being in a very nervous, shocked state. She composed a letter to Arthur Smith, back in Yonkers, in which she said:

I will try and write a few words to ease your mind & my own. You know of my dreadful trouble. I am thankful to God I am alive & no limbs are broken.

My darlings are gone, also dear Alf Bessie, Baby. Helen & myself left…I swam for my life & was picked up by some fellow pulling me on a collapsable boat (I can’t spell today).

I had a terrible experience. I am thankful I have my mind also limbs which are bruised all over. I am under a doctor’s care and feel better than I did, but oh my heart aches & will always.

My dear boys were with me five minutes before it happened but I never saw them again……

Oh Arthur this is a dreadful blow. Everything I possess is gone and my darlings as well. Also our dear Alf and his lot……I am trying to be brave. God will still give me strength to overcome this as he saved me for some purpose.

Your broken hearted sister. CE

How must dear Hubert feel? I have not heard yet. Only cablegrams.

There was one additional sorrowful burden for Cecelia. Her older son had not wanted to make the trip. He wished to remain with his father in Pennsylvania, but had been compelled to go.

|

| A page from the Helen Smith scrapbook kept by the Arthur Smith family of New York, showing the most widely reprinted photo of Helen. |

|

| Helen Smith and Ernest Cowper |

|

| Helen Smith and The Owens Brothers. Courtesy of Carol Keeler |

|

| Smith family |

Helen Smith; Alfred and Elizabeth Smith

The photograph of Cecelia Owens’ niece, Helen Smith, 6, wearing her white hat and holding her doll remains one of the most frequently reprinted, and best known, of the Lusitania disaster images. In its day, the photo charmed royalty, and induced a substantial number of adoption attempts in the weeks following its initial publication: 90 years later it retains much of its original power to charm, and elicit sympathy for the young orphan.

Alfred and Elizabeth Smith likely remained aboard the Lusitania to the last. It is reasonable to assume that, after parting company with Cecelia Owens, they continued to search for their missing daughter until time, and escape options, ran out. They died not knowing that Helen had been rescued, with relative ease, in one of only six lifeboats successfully lowered.

It is difficult to imagine what Helen Smith must have experienced that afternoon. Alone on deck, awaiting the return of her cousins, she would have heard, and possibly seen, the explosions forward on the starboard side. She would have felt the ship beginning its first roll to starboard, and may have witnessed the first lifeboat to upend and eject its passengers. She would definitely have seen the waves of passengers coming up from below. What she did not see in the mass of people, was any sign of her parents or extended family. Fate interceded, and Helen’s life was saved by the appearance of Toronto newsman Ernest Cowper:

I was chatting with a friend at the rail about two o’clock…we both saw the track of a torpedo, followed almost instantly by an explosion. Portions of splintered hull were sent flying into the air… A little girl, whose name I later learned was Helen Smith, and whose age is only six, had become separated from her parents in the rush and appealed to me to save her. I put her into a lifeboat and looked for her parents but could not find them. Whether they were saved or not I do not know.

Survivor Elizabeth Hampshire recalled being with Helen in the lifeboat.

I had a little girl on my knee in the lifeboat. She told me she was called Helen Smith.

As they waited for rescue, Helen turned to Elizabeth and her foster sister, Florence Whitehead, and said,

If I can’t find my Mamma and Daddy, I’ll go with you ladies.

It seems that Ernest Cowper served as Helen’s unofficial guardian in Queenstown. A photograph of him holding the child was printed in dozens of newspapers. He was mentioned, and quoted, frequently in newspaper columns and through him it is possible to document much of Helen’s immediate post-sinking experience:

Ernest S. Cowper, a Toronto journalist who saved Helen Smith…said that he had given her up in Queenstown to a well-dressed woman whom asserted that she was the child’s aunt:

“I think that it was just simply a wealthy woman who read the story and wanted to adopt her,” he added, “because later I had twenty two offers in Liverpool through the Cunard Line, from people wanting to take Helen Smith. Before I left London I received a letter from Queen Dowager Alexandra, asking me to take her to Sandringham, but I could not go as I did not know where the child was, and my wardrobe was not exactly fit for making calls on Queens living in royal palaces.”

Although the Royal Invitation story seems to be a newspaper fabrication at first glance, a letter from Queen Dowager Alexandra inquiring about Helen survives in the Smith file in the Cunard Archive.

There was at least one Helen Smith newsreel produced during the week after the sinking.

Helen was claimed by her uncle, Captain Smith, and returned with him to Swansea. There she was allowed to fade from the limelight and lead as normal a life as possible under the circumstances. A clipping from the 1920s quoted Ernest Cowper as saying that he kept in touch with Miss Smith and that he was proud that she had received an award for academic excellence.

A bizarre footnote to Helen’s tale appeared in the early 1930s. A female “Lusitania orphan” close in age to Helen, had been murdered and cemented under a garden pool by her adoptive father, who committed suicide by jumping from a ferry the day the bodies of the girl and her mother were uncovered. Whether the girl truly was a Lusitania orphan as early press accounts claimed, and what her true identity was, remains to be discovered. However, it can be said with assurance that she was not Helen Smith. Helen had married John Henry Thomas, a wholesale department manager, in Swansea in late 1931. They had at least one child, a daughter, and continued to live in peace and comfortable obscurity for the remainder of their lives. She kept in contact with friends in Ellwood City well into the 1940s. She was interviewed by Hickey and Smith (credited as Helen Thomas) for their book, and survived more than a decade beyond its publication, dying in Swansea, where she had been born in October 1908, on April 8, 1993.

Frederick Warren Pearl; Amy Pearl and children

Amy Pearl, Frederick Pearl

Surgeon Major Frederick Warren Pearl embarked on the Lusitania’s fatal voyage with his wife, Amy, four children: Stuart, Susan, Amy, and Audrey. Two servants, Alice Lines and Greta Lorensen were traveling with them were. The Pearl party was more fortunate than most, although two of the children, Susan and Amy, and one of the servants, Greta Loresen, were lost. Major Pearl’s checklist-style deposition, although spare, captures the horror facing separated families during the final eighteen minutes.

- About 2 p.m. went below deck sixteen feet above water.

- Quarter hour later heard explosion on opposite, or starboard, side

- Flames smoke and glass in stateroom

- Wife on deck at time saw torpedo coming from starboard, which hit about 8 seconds later.

- Wife went below

- Put on life belts excellent sustaining power, deck crowded no panic.

- From wake it appeared ship had made a semicircle to port since hit.

- Nurse, stewardess and three children separated from wife and one child.

- Ship now listed to starboard

- Searching for nurse and children, I found two boats lowered starboard and third suspended perpendicularly while women were being put in fourth.

- Still no confusion.

- Back to wife.

- Word came lower no more boats, everything alright, aid coming.

- Made second tour for children vainly.

- Ship now on fairly even keel.

- Boat filled with people crashed inward falling on other people on deck.

- Ship suddenly made a forward plunge to starboard, water rushing in over forecastle head and deck.

- Third search for children vain.

- Back with two planks for wife, nurse and child when sea came rushing aft throwing everyone on deck into sea as ship plunged beneath.

- Pulled down five or six times by suction

- After three hours in water was picked up by a collapsible boat in which discipline excellent.

- Picked up 35 in all.

- About one hour later taken off by steam trawler which rescued many others, reaching Queenstown about six hours after sinking of the ship.

- Wife had been pulled on to an overturned boat with about fifty people.

Major Pearl died on January 2, 1952, at age 83 in London, England. His wife, Amy also died at age 83, on February 1, 1964. Their son, Stuart, 5 in 1915, outlived his mother by little more than a month, dying in Arizona at age 54, on March 13, 1964. The Pearl’s infant daughter, Audrey, is one of two known survivors still alive as of 2008.

Paul and Gladys Crompton, and children

One of the most tragic stories of the Lusitania disaster was that of Paul Crompton, his wife Gladys, their six children and nursemaid Dorothy Allen. The Cromptons were perhaps the most widely traveled family aboard the liner: Mr. Crompton’s business had taken to points as far removed from their native United Kingdom as Vladivostok, Russia, and Brazil. They had spent nearly a decade living in Chestnut Hill, Pennsylvania. Their governess was an ambitious college graduate from a well-to-do American family. None survived.

Gladys Crompton and Family

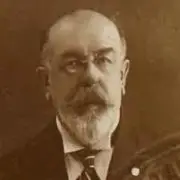

Paul Crompton was born on August 20th 1871, one of two sons born to Barrister Henry Crompton, and his wife Lucy Henrietta Romelly. Paul and his younger brother, Davis, spent their childhoods at Churt House, Frensham, Surrey. Both were fluent in French and German, having been taught by their governess. Henry Crompton eventually became the Clerk of Assizes on the North Wales Circuit. The family continued to reside in Frensham.

Paul Crompton’s wife, Gladys Mary Salis Schwabe, was born on February 3rd 1878 at Cumbersall House, Lancaster, daughter of George Salis Schwabe, Major of the 16th Lancers, and his wife, Mary Jacqueline James. Gladys’s travels began almost at birth: as the daughter of an army officer, she and her mother and siblings followed Major Schwabe to various posts across the United Kingdom. By 1898 Schwabe had been appointed Major General of the Royal Hospital Chelsea; home of the famous Chelsea pensioners.

It was while in London that Gladys Mary met and became engaged to Paul Crompton – by then a successful merchant. They were married at St Luke’s Church Chelsea on October 24th, 1900. The couple moved into Paul’s home in Mecklenburg Square, Clerkenwell after their honeymoon.

The Crompton’s Home at Mecklenburg Square

Courtesy of Cliff Barry

The Cromptons spent a great deal of time in the Far East during the first years of their marriage. Paul learned to speak Chinese during their time in China. In 1902 while in Vladivostok, Eastern Russia, their first child Stephen was born. Their daughter, Alberta, was born in New York during the return leg of a trip to Brazil. By 1905, the family had expanded to include Catherine Mary, who had been born in London, while the family, who were living in China, had come home for a family funeral.

1. Peter Crompton, 2. John Crompton, 3. Alberta Crompton, 4. Catherine Crompton, 5. Dorothy Allen, 6. Stephen Crompton

Courtesy of Cliff Barry

The Crompton family settled in Philadelphia, where Paul worked as Vice President of the Surpass Leather Company. He was based in the company offices at 901 West Moreland. The Surpass Leather Company manufactured most of America’s kid leather, and had a virtual monopoly on patent leather. The president of the company was Charles Booth, who offered Paul a directorship with Booth Steamship Company.

The family continued to grow, with Paul Romilly born in 1906, and John in 1909. Chestnut Hill, on the outskirts of Philadelphia, seemed the ideal place for the children to grow up. Paul Crompton became a member of the Philadelphia cricket club. His brother, David, lived with the family and was based in the New York office of the Surpass Leather Company, and served as the company treasurer. Gladys Crompton engaged the services of a young Mount Holyoke graduate, Dorothy Allen, to provide games and activities for the children in early 1913. Dorothy left her position with the Crompton family a year later, but soon returned to serve as governess.

Dorothy Allen

Courtesy of Mount Holyoke College Archives and Special Collections

Gladys gave birth to her last child, David, in 1914. Less is recalled about Mrs. Crompton than of her husband. Her life seems to have been similar to that of any well to do mother of her era. She maintained affection for the Orient, and after her death one of the reported ’human interest’ details about Mrs. Crompton was that she was well known for shopping at the Chinese department of Wanamaker’s department store.

Business continued to take Paul Crompton back and forth the Atlantic, and on nearly every occasion his wife and children accompanied him. They usually traveled aboard the Lusitania. It became apparent to Mr. Crompton, by early 1915, that his financial interests in England made it imperative that he reside there. It was later said that the Booth Steamship Company had made him a handsome offer, the specifics of which possibly required the move.

Crompton initially took passage for himself and his family on a Dutch steamer, but because it did not provide direct passage to England, he cancelled the booking. He then booked passage on the Lusitania. The family intended on taking up residence at 29 Gilston Road, Kensington, Middlesex, upon arrival in the United Kingdom.

The family traveled up from Philadelphia accompanied by Hollister Sturges, a business associate, who waved them off after the gangplank had been withdrawn. They were allocated cabins on the Upper Deck, D58/60/62/64, which were located by the main entrance to the first class dining saloon, on the port side. It may have been this young boisterous family that had caused Theodate Pope, in cabin D54, to seek a quieter cabin on A Deck She later wrote of a noisy family who made her stay in D-54 unpleasant. Mr. and Mrs. Crompton would dine in the first class saloon, while the children ate in their own dining room on C Deck. It was later said that, during the voyage, Paul Crompton had received a cable from Alfred Booth telling him to disembark at Queenstown and proceed directly to London.

Theodate Pope

There were only two recorded sightings of the Cromptons on the day of the disaster. The Reverend Cowley Clarke said:

Whole families have been lost. One American family, Mr. and Mrs. Paul Crompton, Philadelphia father and mother, and six children, down to a baby of eight months, were lost. I tried to find one of the children, but it was absolutely hopeless to find anybody.

Samuel Knox, of Philadelphia, remembered seeing the family and recorded:

Paul Crompton

I saw Paul Crompton, of Chestnut Hill, with four belts for his little children. He was trying to fasten a belt around the smallest, a mere baby. One of his older daughters, a girl of around 12, [possibly Alberta] was having trouble with the belt she was trying to put on herself. ‘Please will you show me how to fix this?’ she asked unconcerned. I adjusted it, and she thanked me.

Immediately after the disaster Charles Booth cabled Hollister Sturges in Philadelphia for any news of the Cromptons, but to no avail. It quickly became apparent that none from the large party had survived, and a photo of Mrs. Crompton and her children was released to the press and became an iconic image in the Lusitania story, and an effective piece of wordless propaganda.

The funeral cortege for the body of Stephen Crompton, identified as body 134, left the Cunard Offices in Queenstown, at 11 o’clock on May 13th, for the old church graveyard. The Chairman and Town Clerk of Queenstown, and town official representatives were in attendance. A number of prominent Queenstown residents were also present. The body was interred in a private grave large enough to hold the entire family should it be needed. The bodies of 6 year old John, # 192, and 9 month old Peter, # 214, were buried on May 16th. The remains of the rest of the family, if found, were never identified and the grave was closed.

David Crompton, who was in Philadelphia at the time that the Paul Crompton branch of the family was eradicated, closed the house in Chestnut Hill and let the servants go. He then returned to London. Probate was awarded to Paul Crompton’s mother and brother as none of the direct family had survived. Paul Crompton’s estate was valued at £30, 158, 5s, 9d; net it was worth £28, 709, 1s, 7d. Neither the Crompton nor Schwabe families made application for compensation after the war.

The Crompton’s Grave

Courtesy of Cliff barry

Today row 15, grave number 12 marks the final resting place of the three young Crompton brothers. No headstone exists but metal railings surround the grave, slowly rusting away. The final picture taken of Gladys Crompton and her six children was publicised worldwide to highlight the horrors of the German atrocity; a purpose for which the image is used to this day. Perhaps it is a fitting tribute to such a young family cut down in their prime.

Dorothy Ditman Allen remains best remembered as a footnote in the tragic tale of the Crompton family. Dorothy was the middle daughter of Dr. Richard Allen of Frankford, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. The Allen sisters were afforded “rare educational advantages,” with two becoming teachers upon graduation from college and the third, Dorothy, becoming a governess to the Crompton children in 1913, after her graduation from Mount Holyoke. The ‘acting bug’ may have bitten Dorothy, for she appeared in at least one college production.

Miss Allen was lost, and very little detail survives regarding her final seven days. She was seen to be crying on sailing day, which is often attributed to the behavior of her charges. However, she had worked for the Cromptons for two years at that point and was, presumably, used to the childrens’ high spirits. It is more likely that her tears were induced by some other factor; fear of the German warning, and of a wartime crossing, perhaps? No one who survived recalled seeing Miss Allen. Three of the Crompton children were recovered and buried in Queenstown, but Dorothy Allen was never found. Her family sent the consulate a description in hopes of identifying her body. They said she was “five feet, blue eyes, stub nose, twenty six years old.”

Dorothy had helped to support her widowed mother, Hettie, with an annual contribution of approximately $300.00. She had spent her free hours helping her sisters to maintain Hettie Allen’s house. In 1924 the U.S. Mixed Claims Commission awarded Mrs. Allen $7500.00 for Dorothy’s loss, plus a second sum of $1267.00 to be awarded to her as Administratrix of Dorothy’s estate.

More fortunate than Dorothy Allen was Gladys Crompton’s maid, Jenny Murphy. Miss Murphy gave notice before the voyage that she was resigning from her job, after six years, to marry Patrick Gallagher, an estate gardener. They wed shortly after the Cromptons left Philadelphia. She declined to comment about the Cromptons in public after their deaths, saying that it would seem out of place.

Image courtesy of Harald Advokaat

Charlotte Pye was a young mother from Edmonton, Alberta, Canada, traveling in second class with her infant daughter, Marjorie. Her husband, William, remained behind to tend to the family tailoring business, the Pan-Co-Vesta Pantorium, while his wife paid an extended visit to her parents in the United Kingdom. It was to him that Charlotte sent a graphic account of the disaster a few days after her safe arrival in London:

Charlotte Pye and Marjorie Pye

Courtesy of Kevin Spaans

I scarcely know how to begin this letter, so much have I gone through since I parted from you…we were sitting at luncheon when the torpedo struck us. A few minutes earlier I had been talking with a woman who sat opposite me, and I told her I intended upon staying on deck all night as we were in the danger zone and I feared something might happen. ‘They daren’t do any such thing’ (meaning the Huns) and then the crash came. Everybody stood up, and my friend shouted ‘She’s going down!’

I picked up Marjorie and ran on deck. The ship had listed to starboard and the decks were slanting so much that it was almost impossible to walk on them. My head was banged several times, but I still managed to hold on to Marjorie… I saw the poor women running up and down…I did not have a lifebelt, but a gentleman took off his and strapped it around myself and the baby. When my turn came to get into a boat, Marjorie was taken away and handed in first, and I followed. Barely had I got into the boat and taken the baby into my arms when I looked up and saw the big ship coming right over on us, with people jumping for their lives. Then our boat suddenly keeled over and we found ourselves in the water. Marjorie gave one piercing scream and we both went down together. The suction underneath the water dragged her out of my arms and she was gone forever. I shall never forget the agony of it: while I was under the water I felt my end had come.

Charlotte rose to the surface only to be dragged under a second time, losing consciousness. She awoke in a field of debris, and clung to wreckage until three men pulled her atop an upturned lifeboat.

On one side of the boat a lady was lying dead, and all around us in the water were the dead bodies of people who only a few hours before had been bright and happy.

Mrs. Pye was rescued by the vessel Flying Fish and brought with the others into Queenstown. She traveled on to England. Searchers in Queenstown eventually found Marjorie’s body, which was buried in Private Grave #5, row 17, with the body of an unidentified 12 to 18 month old female sharing her coffin. Charlotte coped with her loss by throwing herself into the War Effort, appearing as a speaker at several recruitment rallies: a film of one of these appearances has survived. She wrote a letter to the mother of victim Richard Preston Prichard, months after the disaster, in which she spoke of how tight she had held her daughter under water, not relaxing her grip until she lost consciousness, and of how her life no longer seemed to have any meaning with Marjorie dead.

Charlotte Pye Bergen was awarded the sum of $3265.00, in the Canadian courts, for her injuries and losses aboard the Lusitania, in 1926.

Late in her life, as Charlotte Kelly, she granted an extended audio interview during the course of which she related her Lusitania experiences. She died in Vancouver on January 18, 1971, at the age of 84.

|

| Gertrude Adams Daily Sketch Jim Kalafus Collection |

|

| Joan Adams Mike Poirier Collection |

Gertrude Adams’ experience paralleled that of Charlotte Pye. Mrs. Adams, a second class passenger returning to Bristol, England after a stay in Canada, was in the dining saloon with her two and a half year old daughter, Joan, when the explosion came. She described it as a “dull boom” and a “slight tremble” and told of how, as the passengers started for the doors, a crewman tried to calm them by speculating that perhaps they had run aground.

Gertrude Adams (seated centre at back) in 1910

(Courtesy of Roger Pollett)

Mrs. Adams made her way to the boat deck, and from there followed a group of passengers obeying a “women and children this way” order to the Promenade deck. Mr. Basil Wickings-Smith gave her his lifebelt when he saw that she had none. Gertrude witnessed another young mother and child hurled down the sloping deck, as the ship listed, landing against a flight of steps. Shortly thereafter the Lusitaniasank and both Mrs. Adams and Joan were pulled down with her. Mother and daughter came to the surface together, and Gertrude swam to a piece of wreckage upon which she placed her daughter.

But I could not help her more than hold here there.

The water, although not as quickly fatal to those immersed in it, as was the water into which the Titanic victims were plunged, was dangerously cold and Joan soon began to fade.

Then, I had to watch her die. A young fellow near offered to take her while I tried to reach a tank that was floating a little way off, but my baby had passed away then and I felt I must kiss her goodbye.

Mrs. Adams, the young man and several other people clung to the tank in the numbing water for hours.

One of the men later capsized the tank and I and the others were again in the water. It was twenty-five minutes after of two when I first entered the water and I was picked up at ten minutes of six. A boat took us to a trawler, and by that time I was delirious, awakening to find myself in a bunk of the trawler with the recollection of what seemed like a horrible dream in my mind.

Robert Henry Duncan confirmed part of Mrs. Adams’ storybefore Lord Mersey:

A: A Mrs. Adams of Bristol, I found out…There was another lady and gentleman on the tank, but the gentleman died from exposure and the lady got hysterical and we lost her too.

Mrs. Adams was taken to Queenstown, and from there journeyed on to her mother’s home in Bristol. She was joined there by her husband, a stretcher bearer with the 4th Battalion, Central Ontario Regiment. She would later write to the mother of victim Richard Preston Prichard that at least she, Gertrude, had the small comfort of knowing her child’s fate, unlike so many other Lusitania parents who were forever left to wonder.

Gertrude Adams in Australia in the 1960s

(Courtesy of Roger Pollett)

Gertrude Adams’ Account

Some months after my husband went with the Canadian forces to the war, I left our home in Edmonton, Alberta, to visit my parents in Bristol, England. I wanted to sail on the biggest boat which made the run, and I had many pretty clothes for myself and my baby.

The war was still remote to me. When I stood at the wharf with my bags, a stranger said to me “Don’t you know there is a war on? It is not safe to sail!” But, I had no doubts about my safety. When the ship was camouflaged, I did have a moment of worry, but not for long, and as we neared home I worried less.

We had just finished lunch in the second saloon when the explosion came. There was a violent explosion, furniture crashed about the saloon, and women screamed. I grabbed my baby. I remember a young woman who put out her hand to help me as I struggled with my baby up the stairs. I reached the deck and found a boat covered with canvas, and a man standing by it. The sweat was running down his face, and he was saying that he could not get the canvas off by himself. “I can do nothing for you, missus’ he said. The ship tipped right over to one side, but I hung on to the boat and sat my baby on the canvas cover. She did not cry.

Someone called to me to follow, and I took my baby off the boat and ran with a man and another woman with a baby to the first class deck. Nobody told me where to go to get a boat, but I remember picking up a traveling rug someone had dropped and thinking I would need it for my baby- later.

The woman with the baby fell down on deck, and rolled, and a wave took her and the child. The man asked a steward to get me a lifebelt, but the steward replied “She will have to get her own.” The man took off his belt and gave it to me, and the next minute he was gone down the deck himself. He came from somewhere near London- Blackheath, I think. He left a wife and a little girl.

Then I went down the deck and I was washed overboard. I held on to my baby and I seemed to go down, down to the bottom of the ocean. When I came up, I still had the baby, but had lost the rug. I found a board floating in the water, and I put my baby on it. I floated there with hundreds of people all around me….there was no way of getting to the boats, and they were all overcrowded anyway. Then I saw that my baby was dead, and I let her go, and slipped back into the water. I felt there was no use struggling anymore, but three seamen on a tank reached out to me. One man was balancing the tank, and the rest of us clung to the edge. I heard them arguing as to whether I was dead or alive, but they held me up.

I remember seeing a barrel floating, and thinking “If only I could get to that barrel, if only I could” but, of course, it was quite impossible. I had thick plaits of hair, and felt that my hair was holding me down in the water. I do not remember anything much until we were picked up by a boat from the coastal steamer Bluebell.

Well, everything was lost, except my husband. He secured a special permit and came from the front line to spend four days with me in Bristol, and saved me from going mad.

Gertrude Adams had three children after the war, and emigrated to live in Hurstville, Australia. She died there, on December 20, 1981, at the age of 91.

Sarah Rose Lohden, of Balmy Beach, Toronto survived the disaster, as did her eleven year old daughter, Elsie:

All during the voyage we were all talking of submarines. It seemed people could do nothing but discuss the possibility of attack. I had a presentiment we would be struck. I could not sleep night after night, but walked the decks, thinking what must happen.

On Friday, immediately after a meal I was on the promenade deck with my daughter. Looking over the deck I saw the periscope of a submarine…

A big explosion followed. It was then ten minutes past two. There was a scene of great confusion. Many boats failed to get off.

Survivors photographed at Queenstown

Left to right: Mr. Collis, Mrs. Wolfenden, Mrs. Plank, the Lohdens, Mr. Milford.

A young Spaniard, Vincente Egana of Bilbao, showed great gallantry. He saw Elsie and myself into the last boat that left, then went back and brought other women and children.

The scene as the ship sank was terrible. The whole surface of the water seemed covered with floating articles, particularly deck chairs, among which multitudes of struggling people fought for life. As the ship heeled over, a funnel came almost on top of us, brushing by me. We were caught in the wireless rigging, but finally got free. We were four and a half hours in the open sea before our boat was rescued with about twenty men and women, and two children.

The most moving case I witnessed was Mrs. Adams; I believe the wife of a soldier. She had a two year old baby. She fell into the sea clasping it; caught a steamer chair; put the baby on it and held it there, she floating by its side.

As we drew near we saw the baby was already dead from drowning and exposure. We went to pull her in to the boat. “Let me bury my dead child first” she whispered. She let the babe sink as we dragged her in.

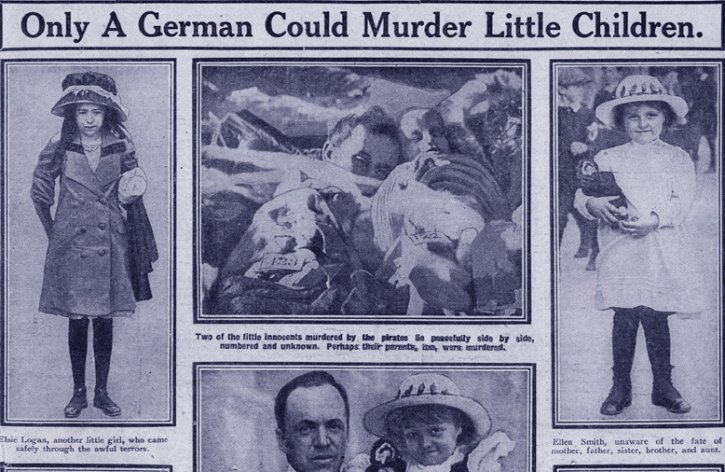

How the U.K. and much of the U.S. viewed the disaster.

Under the headline are shown (left to right) child survivor Elsie Lohden; a photo taken at one of the morgues in Queenstown showing the remains of waiter Charles Gilroy, infant Sheila Ferrier (on Gilroy’s chest) and infant Walter Dawson Mitchell Jr, and the omnipresent photo of Helen Smith. In the cases of Sheila Ferrier and Walter Dawson Mitchell, the children were survived by a mother widowed by the sinking.

Copyright The Daily Sketch. Jim Kalafus collection.

Sarah Lohden Pinden died on October 20, 1932, in Toronto, Canada. Rose Lohden Green died in Peterborough, Canada, on November 24, 1987.

A police report discovered by Peter Kelly details a story as grim as those of Mrs. Pye and Mrs. Adams. Four bodies were recovered along the south coast of Ireland, and upon being brought ashore were examined and photographed. Three proved to members of one family: Mrs. Emily Palmer, and her sons Edgar (an infant) and Albert. The report is full of minute details and one horrible one. Mrs. Palmer stood 5’2”, had light blue eyes and an oval face, and died wearing a blue corded skirt and brown tweed jacket. Her 7 year old son also had blue eyes, and wore a Lusitania souvenir badge. Mrs. Palmer had time to “attach” her infant to her body while still aboard the ship. When all three were recovered, they were lodged beneath an overturned lifeboat found drifting off Baltimore, Ireland. A notation found elsewhere indicates that his grandmother identified the boy’s body, using the photograph that remains with the report. Emily’s husband, Mr. Albert Palmer, and their four year old daughter, Olive, were never found.

“Those dirty hounds murdered my wife and her unborn babe. They may get me, but I will wipe out my score first.”

So said Constable William Smith of Hamilton, Ontario, as he resigned from his job and enlisted, on May 13th, 1915. His wife, Minnie, had been a third class passenger aboard the Lusitania, and by May 12th there was no chance that she and her unborn child would be found alive.

Norah Bretherton and family

Courtesy of Paul Latimer

A fairly large number of pregnant women boarded the Lusitania on May 1st. Florence Padley and Gertrude Wakefield were both within days of giving birth, and would each deliver a healthy son soon after reaching shore. Margaret Kay was also days away from giving birth, but reached the boat deck just in time to be washed overboard as the ship sank, and was never seen again. Emily Anderson and Norah Bretherton each survived to give birth to sons in the fall of 1915. The child that Amy Pearl was carrying when she sank with the ship was born late in the year. Annie Elliot lost her husband, Arthur, on May 7th, but carried their unborn child full term.

Nina Holland gave birth to a daughter, Eileen, in September. Catherine Henry gave birth to a healthy son in the fall of 1915, who she named Michael Lusitania Henry. And the luckless Minnie Smith? A unidentified body, buried in the Old Church burial ground at Queenstown, was described as such:

186. Female. 32 years, pregnant, stout strong build, fair complexion, round face, good looking; long light brown wavy hair; height 5’9”.

Wore blue serge dress with red jersey underneath jacket, blue check bodice, black button boots, cashmere hose.

Property. Gold wedding ring and keeper rings.

William Sterling Hodges, of Philadelphia, was one of several passengers on the fatal voyage to have crossed on the Lusitania’s final completed trip, which commenced in Liverpool on April 17th 1915, and ended in New York on the 25th.

William Sterling Hodges, Sara Hodges and the Hodges Boys

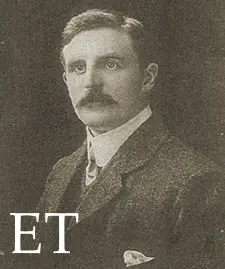

Mr. Hodges, 36, had been in the employment of the Baldwin Locomotive Works, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, for 16 years in May 1915. He first worked as a draftsman for the company, then in sales, finally becoming a mechanical engineer. He represented his company in China and Russia. In community life, he was the organist at Harper Memorial Presbyterian Church in Philadelphia, where his family resided at 2936 West Lehigh Avenue.

Hodges had been appointed manager of his company’s Paris offices, in which capacity he made at least two transatlantic crossings. One odd note: William Sterling Hodges appears on a December 1914 Orduna passenger list, the next passengers upon which sequentially are the Mrs. Mary Hoy and her daughter, Elizabeth, whose deaths aboard the Laconia in 1917 finally propelled the U.S. into World War I.

Mr. Hodges was to take charge of the Baldwin office in Paris, where he would sell locomotives to the French government and supervise the assembling of engines sent to France in pieces. He had set up a household in Paris; his trip to New York was to be a fast turnaround, for the sole purpose of shepherding his family to Europe.

He had an important sales meeting in Paris on the May 10th,and subsequently had only five days to spend in the United States. Passports were applied for and given to Mrs. Hodges and her two sons on April 27th. The day before he sailed with his wife, Sara, 32, and two sons, William Sterling, 7, and Dean Winston, 4, Mr. Hodges signed a new will appointing Sara his heir. The will also contained the ominous note that should they “all die simultaneously or on or about the same time” his estate, consisting principally of an $11,000 insurance policy, would go entirely to his mother.

The family boarded the Lusitania and was assigned cabins A16/18. It is known that they spent time during the crossing with Mr. Harry Keser and his wife Mary. It was rumored, but never confirmed, that Keser, who was Vice President of the Philadelphia National Bank, was engaged in business with Mr. Hodges’ firm.

One account of the sinking briefly mentions an encounter between Mrs. Maud Thompson, survivor, and the Hodges family in the crowd climbing the stairs to the boat deck. Another states that Mr. Hodges was later seen exiting his portside A Deck cabin with lifebelts in his arms.

Maud Thompson

Initial reports stated that 4 year old Dean Hodges was the sole survivor of the family. His uncle told the Philadelphia Enquirer that he intended to stand by the boy and raise him, but the rumors proved to be false and his body, like that of his father, was never recovered. There were photographs of Mr. Hodges and his sons in The New York Times, Sunday, May 8, 1915 edition.

The Monday, May 17th, issue of The New York Times said that Dean’s body had been recovered and identified. The body, #220, proved to be that of his brother, William. Sara Hodges’ body, #209, was interred in common grave B, on May 16th, as one of the unidentified. She was subsequently identified, too late to be brought back to the United States. Department store magnate John Wanamaker interceded on behalf of Sara’s parents, who wanted Sara exhumed and brought home. Letters were exchanged in which Cunard and Queenstown authorities repeatedly reminded Wanamaker and his lawyers of the great costs, and many legal hurdles, to be faced in disinterring Mrs. Hodges, and eventually the matter was dropped and she remained buried in the mass grave.

The body of William Jr. was brought back to the US, on May 26th, aboard the SS Philadelphia and interred in Monument Cemetery, Philadelphia. Monument Cemetery was demolished in 1956/’57 and the bodies buried there, including William Hodges Jr., were exhumed and reburied elsewhere.

William Sterling Hodges’ mother gave an interview in which she stated

I felt that it was foolish and risky for them to start off on that boat with all the doings of the Germans around the English coast. Of course my son had to go because business demanded his presence in Paris, but did not seem sensible for his wife and children to go too. My son is only thirty six years old, and he has been away for such a long time.

Sara Hodges’ recovered personal effects were returned to the U.S on the RMS Cameronia, which sailed from Liverpool to New York on September 26, 1915. They were handed over to William Hodges’ mother and brother. They consisted of:

Compensation was awarded to William Sterling Hodges’ mother to the sum of $9,000.00 and to Sara Hodges’ father, Levi Greissmer, the sum of $2,500.00, on February 21, 1924.

Did the young leaves wonder

If the year were all spring,

With flowers there under

And birds to sing;

with no sigh of trouble

Or hint in the tune

That life is a bubble

And death comes soon.

~Algol (Cyril Herbert Emanuel Bretherton)

Norah Annie Bretherton, 32, embarked aboard the Lusitania, with her two children, out of necessity. Her husband, Cyril, a journalist and a lawyer in Los Angeles, had recently found a newspaper job “At a hopeless wage” but with potential for advancement. Norah, in a post sinking letter, described their financial situation as “having gone from bad to worse” and Mrs. Bretherton, four-to-five months pregnant, was traveling to her sister’s home in Bexhill-on-Sea to spend her “confinement.”

Norah Bretherton and family

Courtesy of Paul Latimer

Convent educated Norah immigrated to the United States in 1910, via Antwerp, aboard the Kroonland and had traveled to Los Angeles to marry her fiance, Cyril Bretherton. Their son, Paul, was born in January 1912 and their daughter, Elizabeth, ca. February 1914. The family resided in Santa Monica, while Cyril worked at establishing himself as a journalist. Norah, despite her apparent misgivings over the family’s finances, supported her husband’s ambition, and in a cache of Bretherton family papers on file at Harvard there exists a draft copy of one of Cyril’s short stories with editorial input offered by his wife.

Little remains to document the Bretherton family’s seven days aboard the Lusitania. The family occupied cabin C-14. Norah made the acquaintance of Mrs. Helen Secchi, of New York City and, by her own account, won the ship’s Second Class whist contest. Chances are good that like the other mothers in Second Class she passed most of her time tending to her children: Betty, at 15 months, was attempting to walk and talk, while three year old Paul would have been energetic, and at the exploring stage which requires constant parental attention.

Mrs. Bretherton had a singularly unpleasant time on the afternoon of May 7th:

I had lunched at the first sitting and taken my little girl up to Deck B to play, and put the little boy to sleep in cabin on C Deck. She was on the staircase when the explosions came:

I begged and implored dozens of men on the way to go down and get Paul- they took no notice. One man looked right at me and I knew he had played with Paul, and I said, “You know Paul. Get [word omitted] in the cabin” but he went on. Then I forced baby into some man’s arms who had got to the stairs (I saw a man pull a woman by the arm and get up in front of her) then I ran down to Deck C…I reached my cabin, smoke was coming up through the floor in the hallway and in the cabin, seized Paul and carried him to Deck B. I dragged the boy along- not one of the men who rushed by offered to help me and I saw a woman with a little baby fall and slide along the deck but saw no one help her up…

Norah’s sister offered a detail Norah never made public, in a May 1915 interview. Once she reached the boat deck, Mrs. Bretherton had encountered the man into whose arms she had thrust Elizabeth, but the man no longer had her infant. Elizabeth was lost in the sinking, although whether she was placed into one of the upset lifeboats or simply abandoned by her ‘benefactor’ and lost when the ship foundered cannot be determined.

I heard men’s’ voices saying “Lower, for she’s full, get into the next boat.” I had a friend in that boat, a woman who called out for them to let me in- and she tells me the men did not want me in. This friend, a Mrs. Secchi was the second person to get into the life boat- she found a man already in it. We had a splendid seaman in charge and another of the regular lifeboat crew- there were otherwise 22 men, and 20 women and five children. We pulled away just as a terrific explosion occurred and the Lusitania went down.

Mrs. Bretherton gave birth to a son, Cyril Junior, the following October. Mrs. Bretherton’s days as a Californian were over: Cyril soon joined her in England, enlisted, and although they brought suit against Germany as United States citizens (eventually being awarded $7500.00 for the loss of their daughter and $1500.00 for the loss of their effects) they lived out their lives in the United Kingdom. Cyril Bretherton became a prominent journalist and author, and among the family’s adventures was an incident in which the government had to intercede to save Cyril’s life after he wrote several inflammatory anti-Irish articles during the 1916 uprising.

Paul Bretherton, himself a journalist,served as a wartime correspondent, and wrote the forward to Poems By Algol, a 1945 anthology of some of his father’s better works. Paul married Margaret Clingan in 1944, with their child, a daughter named Teresa, being born in 1945. Relatives of Margaret Clingan informed Mike that the marriage was short lived, and that Paul Bretherton would not have been welcome in their home after the divorce.

Norah, who was residing with her son, John Christopher, in Ramsbury, died of degenerative heart disease on April 29th 1977, at the Cheriton Nursing Home in Swindon at the age of 94. Paul outlived her by only three years, dying of bronchiopneumonia, as a complication of cancer of the vocal cord, on August 19th, 1980, at 68.

The grave of Elizabeth Bretherton at the Ursuline Convent in Cork.

(Peter Kelly)

The Lusitania’s Starboard Boat Deck (looking forward).

From a negative in the Jim Kalafus Collection.

Ruth Logan was returning to Ayr, Scotland, for the duration of the war, along with her two year old son, Robert. Her husband, James, had enlisted early on, had been wounded in Ypres, in November 1914, and by May 1915 was once again at the front. Mrs. Logan was leaving their residence of one year, in Paterson, New Jersey, for the security of her girlhood home. Mother and son traveled in third class, and Ruth Logan survived the disaster. Her account remains among the best of the few left by third class passengers; it begins on a staircase where, at the moment of the torpedoing, the young mother was making her way to the open deck with her child walking ahead of her, so that if he missed a step he would not fall far:

I never let him out of my sight, as I was afraid something might happen to him. There were people coming behind me, and when the shock came we were all jolted about. I immediately seized Robert and ran on deck. The vessel had a considerable list to one side, but she righted herself for a few minutes and several men clapped their hands and tried to reassure us that she would keep afloat. The day before the disaster there were sports on board and as Robert was too wee to take part in the general amusement, I took to running after him crying as I did so “I’ll catch you!” And, oh! The tragedy of it all. When the rush for lifebelts came Robert could not understand it all and lisped the words I had used the day before.

Everybody seemed to be running around, and everybody seemed to be getting lifebelts. I appealed to several, but no one in the excitement heeded me until a sailor came along. I took him to be an officer. “Wait a second and I’ll get you one” he said, and he immediately reappeared with a life jacket and he put it around me. I said to him “What about the child?” and he replied “Put him in along with you” and he lifted my child and put him inside the jacket which was around me. He immediately began to struggle, and wanted down on the deck, and another sailor passing me a minute later advised me to put him down till he could get the jacket put on right. I asked him to get a lifebelt for the wee chap, and he hurried forward to get one, and at that moment the ship went over. I held onto his hood and we went down together, and I still had a grip of him when we came to the surface, but the child’s struggles and the struggling of hundreds of others in the water around me caused us to be separated.

Mrs. Logan was in the water for nearly five hours before she was picked up, unconscious, by a torpedo boat, around 7PM. She was still unconscious when she was brought ashore later that night. She awoke in Haulbowline, where, at first, she assumed that her memories of the tragedy were of a horrible dream. She was able to identify her son’s body in Queenstown, before traveling on to Scotland. Robert Logan, body #42, was buried in Common Grave C, in Old Church Cemetery.

Mrs. Logan’s husband, Corporal James Logan of the Gordon Highlanders, survived the war, and they returned to New Jersey together. They had several more children, including a second son named Robert, but their life together was not to be a long one: the 1930 census lists James Logan as being a widower.

The Marsh family, of Toronto, was returning to their former home in Westgate, England. Thomas and Annie Marsh, and their infant son, Thomas Junior, were among the 601 passengers in the overbooked second class. A few days after the disaster, Mrs. Marsh remembered that her husband had a nightmare in which the Lusitania was destroyed, on the evening of May 6th. She said, of the disaster in which her husband and son were killed:

We came from Toronto to New York and took a berth on the Lusitania, which was sailing on the morning of May 1st; I, my husband, and my eighteen month’s old baby. Mr. Marsh was told that torpedo boats and destroyers would escort the ship some part of the way.

I was sitting, sewing, after I had dressed my baby, when I heard the explosion. Rushing to the steps I saw my husband, who took me to the second class deck. I remained with my husband as long as I could, and tied the baby around me. The first explosion caused the ship to list heavily, which made it difficult to get to the deck. In doing so, many people were thrown down and injured.

I took to the water as the vessel was sinking fast. Within a few minutes the baby got loose, and I lost him. After being in the water for over a half-hour, and only being kept afloat by holding on to two large pieces of wood, I heard a man callout “Come on, lady!” One of the stewards was in the boat, and he assisted me in to it. Later, we were taken to Queenstown.

Annie Marsh was in the lifeboat recalled by several other survivors, in the bottom of which were a dead infant, and several adults, who died of exposure after being pulled aboard.

Annie Marsh Wood died in Faversham, Kent, in early 1977.

Mabel Docherty

Five week old William Docherty, of New York City, was one of only four infants to survive. His mother, Mabel, 29, a former maid, sent this account to her one-time employer, with whom she remained on good terms:

I took the baby down to lunch with me. We had just ordered dessert, and he was asleep. I said to Jessie, ‘After lunch I will take him to the cabin.’ Then the crash came and immediately everyone jumped and made a dash for the staircase.

I stood back with baby. Jessie said ‘Come along, the boat is going down fast.’ The steward took my arm and helped me and took baby up the stairs, and helped us along the deck over a rope ladder into the last boat, just as the funnels came down. Our boat was between them.

We were only about fifty yards from the boat when it went down, and the German submarine was sailing around watching all the people in the water.

The crew was fine, and helped every one, but there was not much chance as she went down in fifteen minutes.

We were picked up by a fishing boat and then by a mail steamer and taken to Queenstown. All this time I never let anyone have baby. I clung to him like glue.

The American Consul took us to his house in Queenstown and treated us beautifully. Then we had to go to Dublin and over the Irish Channel to Liverpool before we got home.

Every one was crazy about baby, as he was the youngest one saved, and at Queenstown the Irish women nearly ate him up. Of course, we have nothing left. All baby’s clothes and mine are gone. But, thank God, we are safe.

Mabel Docherty returned to the United States, where she died at age 77, in Ardmore, Pennsylvania, in May 1966. William Thomas Docherty, Junior, the youngest survivor of the disaster, died in Haverford, Pennsylvania, on October 27, 1972, at the age of 57.

A mother’s love placed Margaret Hastings, of New Rochelle, New York, aboard the Lusitania. Mrs. Hastings had been widowed some years previously. With several children to care for, she chose the best available option and emigrated from Northern Ireland to the United States. She lived with her brother in Westchester County, New York, and worked as a doctor’s housekeeper. Her children remained in Ireland, with her parents. Mrs. Hastings soon saved enough money to bring her oldest son to New York, where he found work in construction.

Margaret Hastings

Margaret often read about the mounting human toll of World War One, and became concerned that her younger son might be forced into service, or enlist. So great was her fear, that she took her entire savings and purchased passage to New York for the boy. She intended to see to it that he arrived safely, and so purchased herself round-trip passage aboard the Lusitania. The North Street travel agent from whom she bought the third class tickets later described her as “preoccupied” and “fearful” about the war. Margaret Hastings was lost in the disaster, and whether her son remained in Ireland or immigrated to the United States has not yet been determined.

Ellis Wilson Greenwood, of South Boston, saw his eleven year old son, Ronald, depart aboard the Lusitania on May 1st. Wilson had lost his wife the previous September.

I only hope my little boy is safe. The boy became very lonesome and even his school days at the Lincoln school could not break his melancholy.

A few months ago his mother’s people in Halifax, England wrote me and said that if the boy longed for somebody to take his mother’s place to send him to them.

Ronald saw the letter before I did and he plagued me to let him go back to England. I told him to wait till warmer weather came, so two weeks ago he again tried to have me send him. So I got his uncle Mr. Spencer of Lawrence, to book passage for my boy and he sailed.

An article in The Boston Globe spoke of how Mr. Greenwood had arranged for a second class steward to look out for his son on the crossing:

Mr. Greenwood was unable to go aboard the Lusitania at New York, but the little fellow was courageous to the end, and with a cheery “Well, never mind, dad, I’ll go aboard alone and find the steward,” he trudged up the gangplank, halting at the top to turn and call back an affectionate “Goodby, dad!”

That was the last father and son saw of each other. Mr. Greenwood knew nothing about the warning, published by the German Embassy against taking passage on the Lusitania.

Boston Globe, May 9, 1915.

Ronald was en route to Northowram, Halifax, Yorkshire, when he died in the disaster.

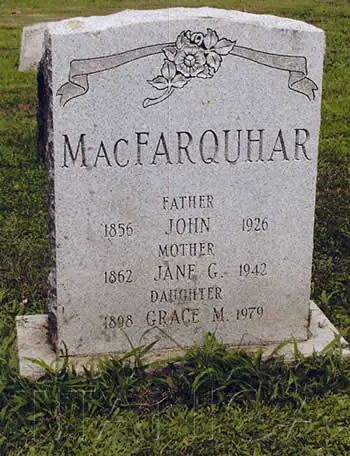

Mrs. Jane Grant MacFarquhar, a woman of about 53 years in 1915, was traveling to Scotland to settle some family financial matters when she survived the Lusitania disaster.

Jane had inherited her father’s estate in Burghead some years previously. Mr. Grant’s will allowed his wife, Jane’s stepmother, the right to use the estate he had left to Jane while she, Mrs. Grant, lived. Mrs. MacFarquhar had learned that the 83 year old woman was seriously, and likely terminally, ill and, in anticipation of her death, was traveling to her paternal home to oversee the eventual disposal of the property. Her youngest daughter, Grace, 16, accompanied her.

Grace MacFarquhar, Jane MacFarquhar

The MacFarquhars booked second class passage on April 27, 1915, and planned for a long stay, of undetermined time, in Europe:

I boarded the Lusitania with all faith in the Cunard Co., as I believed they would never leave New York with so many passengers without being prepared for any emergency. I also trusted in British protection through the war zone, and I thought that a boat of such value to the country would never be left to the mercy of the enemy with its large number of passengers and cargo.

Jane described the voyage as being an extremely pleasant one. And, like many other passengers, Jane would relate that there was a sense of unease as the ship entered the war zone:

The voyage across the Atlantic was ideal. I think a happier company of passengers would be impossible to find. They were of all ages: a large number of babies in their mothers’ arms, children of various ages and men and women up to the age of seventy.

Games were heartily enjoyed on the decks during the daytime and concerts were enjoyed in the evenings-sunshine and happiness making thoughts of danger almost impossible. We had every assurance from the employees that nothing could harm the Lusitania.

On Thursday morning I felt rather uneasy when I discovered that the lifeboats were hung over the side of the ship. On inquiry, I was informed that it was essential that they should be so – according to law. I thought it rather strange that they had not been put ready after clearing New York instead of waiting until we were so near the other side. I noticed the other passengers did not seem to bother, so I also began to forget the lifeboats.

On Friday about an hour before the boat was struck, I stood on one of the upper decks. The view was grand, the sun shining, the water smooth and land visible on either side. As I gazed around the beautiful scene, I thought “Where is the spoken of danger? The end of the voyage is almost in view and we have had no sign of danger whatsoever.”

Jane and Grace spent their final day aboard the Lusitania preparing for disembarkation the following morning. They carefully laid out changes of clothing for themselves before attending luncheon in the Second Class Dining Saloon:

While seated at luncheon, my daughter by my side, I should think about 2:15, I suddenly heard a rumbling noise right underneath our table or so it appeared to me. The noise proved to be the torpedo striking the vessel. Instantly all passengers rose from the tables and made for the staircase as fast as they could. We were amongst the last to ascend…it was with difficulty that we reached the top of the three flights of stairs which led to the deck where the lifeboats were.

Following the crowd to the high side of the vessel and seeing the large number of passengers all along trying to get to the boats, I said to my daughter “There is no chance of safety here, we must try to get to the low side”……it was dare or die. We made the attempt. At one point my daughter went slipping right down to the edge where she caught the iron railing- thus saving herself from landing in the water below. Meantime a steward called for me to go ahead while he assisted my daughter back to where I was. Next we had two first cabin saloons to pass through, which we did from chair to chair. On nearing the entrance which led to the lifeboats, an officer who stood there said “Ladies, stand where you are.” We obeyed and in almost a minute he told us to come right on.

A lifeboat was right in front- almost full; another lifeboat, covered over, lay between. Climbing on top of the covered boat I saw one on the davit about three feet from the sinking vessel…there I made a spring, landing somehow in the lifeboat. I thought my daughter was following my example, but she was stopped, being assisted further back on the boat. The Lusitania had sunk so bad that our lifeboat, when lowered, had only a few feet to reach the water. The sailors had no sooner got the oars when a great cry came from the deck of the sinking vessel- “Row for your lives!” I gave one glance to see if it were really possible that the Lusitania was going down so soon. I quickly turned my head away. The sight was too terrible to see – a deck full of people sinking into the ocean- no fate for them save drowning.

After our boat had been rowed out of danger I turned my head for a last glance. The stern was alone visible. It was crowded with people who seemed to make for the last piece of the wreck left above water, while others unsuccessful in their efforts to gain this temporary safe place, were falling over the side. All around were wreckage and human beings struggling for life. A number of hands were to be seen raised in a signal for help from the boats. Three of these were taken into our boat- all aged people. That was all our boat, with safety, could take on board. I think more were saved from the water than saved from the deck; so many boats were overturned in the lowering.

A British patrol boat eventually picked up the MacFarquhar’s boat, and they were landed at Queenstown around 9PM.

Jane and Grace remained in Scotland for more than three years before returning to Mr. MacFarquhar, and their home in Stratford, Connecticut, at the war’s end. Life was comfortable for the family at first. Grace studied nursing in New York, and graduated as a registered nurse from Metropolitan Hospital in 1924. A biographical sketch of the MacFarquhars published in the 1930s claimed that an unnamed “nervous condition,” which Grace and her mother blamed on the Lusitania experience, deferred her nursing career.

John MacFarquhar, Jane’s husband, was seriously injured during the summer of 1926. He was burned on the face and neck when an elevator motor he was repairing, at the Columbia Records manufacturing plant, in Bridgeport, exploded. He was hospitalized through September 1926. On Christmas day of that year, he went out to his work room, in a small, separate, building behind his family home; Jane found him, near death from a heart attack, on his couch a half hour later. He died before reaching the hospital.

Jane and Grace’s fortunes declined precipitously after John MacFarquhar’s death. They sued Columbia Records, blaming his terminal decline on the injuries suffered in the explosion. Their case was dismissed, then reinstated on appeal. If a settlement was reached, the newspapers did not report it. By the mid 1930s they were living in a small but comfortable duplex at 199-201 Hollister Street in Stratford. One of Grace’s arms was partially paralyzed and Jane, in her 70s, was supporting the two of them by tilling her small vegetable garden at the home she “owned clear.” They were the subject of a newspaper profile on the anniversary of the disaster, which may have exaggerated their penury for human interest, but which contains their last known, and bitter, public statements about the disaster. Jane died, at age 79, on April 21, 1942 and was buried beside Mr. MacFarquhar at Stratford’s Union Cemetery.

Grace MacFarquhar may have returned to nursing after her mother’s death. Details are sketchy, but a letter written by her brother, Colin, in the early 1970s reveals that by then she was under the care of her niece, Mrs. Jane Peck, of Bristol, Connecticut. She died in New Britain, Connecticut on February 9, 1979, at age 80, and was returned to Stratford for burial beside her parents in Union Cemetery. The MacFarquhars share a single stone and are the easiest grave in the cemetery to locate; they are literally the first grave on the left as one passes through the entrance.

James Haldane, en route to Glasgow from Quincy, Massachusetts, survived to relate the final moments of an unknown, doomed, man and child:

Many women put the lifebelt around their waist. As a consequence, they were unable to keep their heads above the water and were speedily drowned.

The most pathetic sight of any which I witnessed was that of a man who strove bravely to save his child- a wee mite of eighteen months or so. I was swimming some distance away from them when they first came under my notice. The man had got hold of a hatch cover and had lifted the child on to it. He himself was in the water clinging to the wreckage with one hand, while with the other he held the child, keeping her in a sitting position. Their case seemed hopeless. The child was about done for when I saw them, and the man was palpably near the extreme stage of exhaustion. He was as white as a ghost.

I turned on my back to rest, and when I looked again the man and child had disappeared, and the wreckage to which they had been clinging was floating away… the impression made on my mind by that little tragedy stamps it the most vivid of all my recollections of the awful time I spent in the water.

Believe Lusitania Survivor Killed

Quincy Man Enlisted to Avenge Outrage.

James Haldane Saw Birth and Death of Big Liner

Aug. 29, 1918: The “J. Haldane” of Quincy, whose death in battle was reported by the Canadian authorities, was probably James Haldane, who was a passenger on the Lusitania when she was sunk off the Irish coast. He was probably the only man who saw the birth and death of the great ship.

Haldane worked on the Lusitania when she was building, several years before he came to this country. He was one of the last men to leave the ship when she was sinking, for, brought up where men build ships, he lived by the creed of “women and children first.” He went overboard when there no more lifeboats or life rafts left.

He was reported drowned at that time, and gave his friends here a pleasant shock when he cabled news of his rescue. He came back to this country several months afterward, and enlisted in the Canadian Army. Reports from him since then have been a bit irregular, and unconfirmed accounts of his death have come here from time to time.

Matron Leitch, who was transferred to the Lusitania from the Cameronia on sailing day, encountered a mother forced into the horrible position of having to abandon one child to possibly save another, as she attempted to escape from the sinking liner.

Just about the time when we were first struck, I, Mrs. Craigie and Mrs. Phillips were in our cabin. We were resting before lunch when the crash came, and Mrs. Craigie said “Come, and get up!” Just then, the water bottle came into the middle of the room, and she said “For God’s sake, come on!”

We ran upstairs, and saw the passengers rushing up….there was a great crowd on the stairs, and we climbed up the steam pipes leading to the bridge.

We found a woman with a little boy, anxious about the welfare of her other child, but we told her to be content with the one she had already rescued. Mrs. Craigie and I took the little chap upstairs with us.

Mr. Jones was lowering a boat, but one side went down first and it filled with water. I then went through the drawing room to the other side, and on the way I met a man coming up with some lifebelts. He gave me two, and I gave one to another woman.

Just then came the second report, and I was swept off the deck. I could not swim, but when I came to the surface a man said to me “Hold on to this chair, and I will look after you.” This man stuck by me while I was in the water for about two hours, and the last thing I could remember him say: “For God’s sake save this girl; she’s dying.” I was then lifted into a little boat, and from there taken to a trawler.

Margaret Craigie and Mary Phillips survived as well, but the identity of the mother and child they attempted to save cannot be determined.

Inez Wilson, 46, who was traveling to Shornecliffe to visit with her husband, a member of the Canadian Expeditionary Force, spoke of another doomed family in her account:

Our lifeboat was almost dragged down with the ship. We could have touched her with our hands, and one man pushed our boat away with his oar against the Lusitania’s side.

We helped in rescuing the people swimming and floating about, ‘though there were over 80 in our boat alone and she was full of water.

A man with another child was trying to get into that boat, too. Before we left the ship he was nearly frantic. “My God” he cried, “I want to save my darling, but they won’t let me in to the boat.” I said “Give me the baby” but he would not give it to me. I could have saved the child, I think, if he had parted with it to me. The poor man was quite distracted, shrieking “My God, they won’t take me.”

Virginia Loney

When one hears the phrase, “poor little rich girl”, it normally conjures thoughts of Shirley Temple, Mary Pickford or Gloria Vanderbilt, but no one is more deserving of the title than Virginia Loney. She was born, on May 19, 1899, to a life of privilege. Her parents were Allen Donnellan Loney, a one time member of the New York Stock Exchange, and Catharine Wolfe Brown.

Mr. Loney had sold his seat on the stock exchange shortly after the birth of Virginia, his only child. He continued to work as a bond salesman and stockbroker, generally earning $10,000 a year. Though well off, his wealth was far surpassed by that of his wife.

The Loneys traveled frequently, alternating between their homes in New York, Maryland and Northamptonshire, England. They are known to have traveled aboard many famous liners, such as the Cedric, Amerika, George Washington, Campania, and Mauretania. They arrived in New York aboard the Olympic on April 10, 1912. Several days into her next voyage, she would receive an S.O.S. from the Titanic.

Their home in England, Guilsborough House, had a stable with twenty hunters, and Allen Loney was considered one of the best riders in the area, and was described as an “excellent whip.” Catharine and Virginia were proficient riders, as well. Virginia learned how to swim while summering at their lake house in Skaneateles, New York.

Virginia and her parents returned to New York, aboard the Celtic, in September 1914, after summering in Northamptonshire. They took up residence at the Gotham Hotel, on Fifth Avenue. Allen Loney returned to England shortly afterwards. He joined the British Ambulance Corps, and supplied his own automobile, which was equipped as an ambulance. He and his chauffeur spent much time in France and Belgium, helping out however they could. Catharine Loney decided return to England and work in a convalescent home. She was to spend the summer caring for wounded soldiers. She also gave permission for two of her cars to be donated for use as ambulances.

Catharine Loney

Her husband did not want his family traveling alone, and so sailed back to the United States, aboard the Adriatic, to escort them. They booked passage on the Lusitania on April 21, 1915. Catharine revised her will shortly before they sailed, leaving her daughter an estate worth over $1,000,000. The family paid $1,020.00 for cabins B-85, B-87, which included a private bath.

Virginia spent most of her time during the voyage with her maid, Elise Bouteiller. Her parents were friendly with Canadian Joseph Charles, of the Musson Book Company, and his daughter Doris. The two families frequently sat in the lounge together, although Virginia had little in common with the older Doris, who was being taken overseas as a precaution. She was involved in a romance with a man named Elliott Lawler, and her parents felt that, at twenty-one, she was too young to get married.

Virginia was resting in her cabin after lunch with her maid, on the day of the disaster:

It all happened so quickly. When the Lusitania was torpedoed, I was in my stateroom. I had no idea what had happened, but joined in the rush for the deck. There, everything was in confusion. My father went down to get some lifebelts and returned with a number, which he distributed around, but did not keep one himself.

The family stood on the portside of the boat deck at the back of a crowd.

There was a lifeboat being lowered and he [her father] saw there was just one place left. He ordered me to get in. I protested, but finally obeyed. It was the last lifeboat launched from the ship.

Virginia looked up from her place in Boat 14, and saw her parents standing at the rail. Years later, she told Adolph and Mary Hoehling that Alfred Vanderbilt was near them. It was a difficult descent, for the liner was listing to starboard. The boat cast off, but the plug was not in and water entered the lifeboat, making it unstable. Boat 14 capsized as the Lusitania sank beside it.

|

| Virginia Loney and Doris Charles Jim Kalafus Collection |

|

| Virginia Loney, ca 1917 Mike Poirier Collection |

The lifeboat was overcrowded and was only a few yards from the Lusitania when the big liner went down. Suction from the sinking vessel caused the lifeboat I was in to capsize. With other passengers in the boat, I was drawn ever so far down in the water. When I reached the surface again, there was nothing to be seen of the Lusitania. People were struggling in the water all around me. I swam to another lifeboat, which was not far away, and was pulled aboard.

She was rescued by a fishing trawler that brought her into Queenstown. There were no sign of her parents or her maid. Joseph and Doris Charles took responsibility for her:

Mr. Charles and daughter, of Canada, who were rescued from the Lusitania were very kind to me, taking me to London with them. I stayed in London overnight, then a maid arrived from my cousins, with whom I was to visit.

Virginia was taken to Guilsborough House. She turned sixteen, but there was little to celebrate. She then booked passage to the United States on the St. Paul. Mrs. Harry Sedgwick escorted her while on board the ship. Many Lusitania survivors were aboard that voyage, including Joseph and Doris Charles, Ernest Cowper, Maud Thompson, James Leary, Charles Sturdy, Ogden Hammond, Daniel Moore, Herbert Colebrook and Percy Rogers,who had also been in Boat 14 with Virginia, among others.

A submarine began following the destroyer assigned to protect the St. Paul during the voyage, People stampeded on deck when they heard that a submarine was sighted. Lifebelts were handed out and lifeboats were readied for lowering. Miss Sedgwick said, “There’s a submarine!” Virginia grasped her arm and cried, “No, no, I can’t stand it again.” The ship arrived on June 13th, and Miss Loney was taken to Huntington, Long Island to be with her maternal uncle, George McKesson Brown. He assumed responsibility for the girl, as did Mary Chamberlaine, who oversaw her care.

Virginia Loney received, outright, property worth $45,000: her mother’s jewelry that did not go down with the ship; $12,000 trust from a great-aunt, and an automobile, among other things. An itemized list of essentials for Virginia’s upbringing was brought to the court’s attention. The list included:

Rent…$5,000

Food and supplies…$4,000

Clothing…$3,500

Three servants…$1,200

School, music and languages…$2,500

Summer vacation and travel…$2,500

Automobile and chauffeur…$2,000

Recreation…$1,500

Maid…$600

Doctors and dentists…$500

Insurance…$200

Incidentals…$1,000Total…$25,500

The Mixed Claims Commission awarded Virginia $26,700 for the loss of her parents. Her uncle George was given $15,450 as executor of Cathe4rine Loney’s estate. Mary Chamberlaine received $1,235 as the executrix of Allen Loney’s estate.

She met Robert Howard Gamble, of Jacksonville, Florida, a few years later, while overseas. He was ten years her senior. Mr. Gamble was an aviator and served in the Naval Reserve. His family was originally from Tallahassee, Florida and Richmond, Virginia. The two were married on April 27, 1918.