The Lusitania : Part 5 : The Struggle to Abandon Ship

Robert William Whaley, John Idwal Lewis and Walter Dawson

Robert William Whaley…

One of the few fortunate aspects of the Lusitania disaster was its timing. The majority of the passengers were high up in the ship, relaxing after lunch, or finishing their meals in the centrally located first and second class dining rooms when the explosion came. There was a brief crush on the stairs in the first few minutes, but it soon eased. Nearly everyone had gotten clear of the lower decks by the time the electricity failed. Those who risked going below for lifebelts described the stairs as clear and the corridors as largely deserted. Few, if any, were alive and trapped below when the ship sank.

The Lusitania listed severely at first and then recovered. This heel and recover pattern would repeat at least twice as she foundered. The list was severe enough, at times, to throw people off balance and give those inside the ship the impression that they were about to start walking along the walls, but most accounts agree that there was a relatively long period in which the Lusitania sat nearly normal in the water.

Evidence from accounts given by a few survivors, among them Major Pearl and Mrs. Bretherton, indicates that the Lusitania was on fire, for a time, during her death throes.

There is an asymmetry of information regarding the behavior of those on board during the disaster’s progress. The crew would later claim that panicked passengers and a careening ship hampered them. The passengers would, almost unanimously, claim otherwise. The details in separate passenger accounts reinforce one another, whereas the details provided by crewmen tend not to match from one account to the next.

Some passenger accounts state that there was crying and jostling on the boat deck as the ship sank, while other accounts say that there was an almost eerie calm among those trapped. Reconciling the two extremes is not difficult, since very few passengers or crew ranged far around the upper decks once they emerged from the interior, and what was true in one area might not have been true elsewhere. The important detail to be gleaned from both view points is that, at their worst, those who waited to abandon ship did not cross over in to mob behavior, even in the final moments when the outcome was evident to all.

The evacuation was catastrophically bungled. At least six boats overturned in lowering, ejecting their occupants, and scant evidence suggests that a seventh boat broke in half. One port side boat was struck by the Lusitania and overturned, as the liner sank beside it, and one starboard boat was loaded, but crushed against its davits and destroyed as the foundering ship pulled it down. Ultimately, seven boats were successfully lowered; six starboard, one port; and several collapsibles washed clear and were utilized by some of those who sank with the ship.

Emily and Barbara Anderson, Assistant Purser William Harkness, and at least eighty other passengers and crew members effected a last minute escape from the ship in Boat 15. Dozens of first person accounts by passengers in 15 have been preserved, and most agree on the important details: the water came up so fast that the boat barely needed to be lowered; the dying Lusitania heeled violently to starboard, throwing water over those in the overcrowded craft, as the huge funnels loomed above them. It seemed as if the funnels were going to crush the boat, and several occupants stated that they seemed almost close enough touch. Others later described covering their eyes in anticipation of the crushing death that seemed only seconds away. However, the liner righted herself as she slid downward, the funnels swung away, and Boat 15 rowed clear. The radio antenna swiped across 15 as the Lusitania vanished, and Assistant Purser Harkness pushed it away. Many more people were soon pulled in from the ocean, bringing the total on board to close to one hundred; nearly one-in-eight of those who survived. All agreed that the boat was so overloaded that less than six inches of freeboard remained. Many of those in Boat 15, including the Andersons, were transferred to Boat 1, which had been lowered with only three or four men in it, when she drew near.

Eighteen minutes after the torpedoing, seven lifeboats, a like number of swamped collapsibles, an overturned port side boat, and perhaps 1600 people drifted within a crescent shaped debris field that was rapidly dispersed by the strong current.

Robert William Whaley, a 31 year old electrician from Victoria, British Columbia, was a second class passenger. He seems to have been one of the survivors pulled into Boat 15 immediately after the liner sank:

I was in the deck smoke room when the first torpedo struck the Lusitania. As soon as ever the noise was heard, there was a cry of ‘submarine.’

The boats were lowered immediately. I was on the high side of the ship when she listed, and I saw there was trouble in getting the boats into the water from that side. One boat, with about twenty or thirty people, which they tried to lower, was dashed against the side of the hull, and the people were flung in to the water.

I could see there was no chance of escape from that side, so I crossed over to the other side of the liner. I helped to lower the last boat that was put off. I could not get into it, but I eventually swung myself down into the water by the rope fall attached to the davit. Once in the water I lost the rope, and down I sank.

When I came up again, the Lusitania was lying right on her side. I cannot swim a stroke, I found myself entangled in the wireless apparatus, but managed to get free. At that instant a boat passed, and I succeeded in grabbing the gunwale, and was dragged into it.

The boat was full of people. We tried to keep away from the suction of the sinking vessel, although as far as I could see there did not seem to be much suction; just a ‘boil’ all over the surface of the water. I could see hundreds of people shrieking and struggling in the water around us, but we could not help them. We took up everyone we could, but it was appalling to see the hundreds for whom there was no help.

Our boat was picked up by a minesweeper, which took us to Queenstown.

Robert William Whaley died in Vancouver, B.C., on October 24, 1952.

James Brooks, of Bridgeport Connecticut, gave this statement a few days after the disaster:

On the morning of the 7th May there was a fairly heavy fog which caused them to continually sound the fog horns and reduce the speed of the ship very appreciably. At eleven o’clock a.m. the fog had lifted to such an extent that over the top of it the coast of Ireland was visible- approximately ten miles away- and speed was gradually resumed until at one o’clock when I left the deck for lunch it was estimated that the ship was going 15 to 18 knots per hour. In connection with the speed of the ship it might be well to state here that at no time during the voyage was there more than three batteries of boilers in operation, being the three forward batteries.

I had finished luncheon at 1:45 p.m., and walked up the grand staircase to the boat or “A” deck as it was termed, and came out on the starboard side, had one or two turns the length of the deck and was then called to the Marconi deck by friends. This was practically amidship and between the four funnels.

After mounting to this deck and talking with friends I crossed over to the port side at the rear of the Marconi house and was called back immediately, and as I approached the rail on the starboard side of the Marconi deck I noticed about 150 yards away the wake of a torpedo approaching on a diagonal course towards the ship.

I said to my friends who were standing near me “torpedo” and stepped to the rail to watch its course. The torpedo was practically 10 to 15 feet long and two feet in diameter, traveling at a speed of about 35 miles per hour. I watched the torpedo until it passed out of sight under the side of the ship, expecting to see the explosion, or the result of the explosion over the side.

Almost instantly, but still with an appreciable interval of time after the torpedo disappeared under the counter of the ship there was a dull explosion, followed instantly by a large quantity of debris thrown through the decks just aft of the bridge and by the side of the forward funnel, followed immediately by a volume of water thrown with violent force which knocked me down behind the Marconi house.

The explosion seemed to lift the ship hard over to port, and was almost immediately followed by a second rumbling explosion entirely different from the first, and the ship was enveloped in dense, moist, steam through which it was difficult to breathe at the point of the Marconi house. After waiting until the steam had blown away from the ship, I went down the ladder on the port side from the Marconi deck to the boat deck, and walked aft to where they were launching the last boat on the port side of the first cabin deck. This boat was filled with women and children and had a few men, including at least three of the crew, aboard. The ship at this time was still moving ahead, but it began to describe a large circle to the port, the Captain evidently having turned his ship towards the Old Head of Kinsale light house which was approximately 10 or 12 miles distant. This boat was lowered to within six feet of the water when the forward tackle jammed and the stern tackle was let go, spilling everyone into the sea with the exception of three men who clung to the boat.

I found standing, in some cases with folded arms, about fifteen of the crew the majority having life preservers on. I asked a group where they obtained life preservers and one replied “over there.” I asked one man if there were any more, and he said he didn’t know.

I then walked through the smoking lounge and through the concert room to the grand staircase. The ship by this time had sunk until the forward deck was nearly awash and it was rather difficult to maintain a footing except by holding on to chairs as I went through.

I came out of the grand staircase again to the starboard side, and walked forward to the bridge, standing within 12 feet when Captain Turner with a life preserver on, standing on the bridge, raised his hand and said “Don’t lower any more boats, it’s all right.”

I remained on the starboard “A” deck watching the efforts, which were entirely detached and not concerted or directed in any manner by any officer of the ship, to launch the remaining boats on the starboard side. The ship had lost way long before this, and was headed towards the Old Head of Kinsale lighthouse, and the sea to the starboard side was covered with a large amount of small wreckage.

I remained amidship on the starboard side until the boat deck was awash and the remaining starboard side boats were in the water but still attached by the tackle and fall and chain at both bow and stern. There had been no effort by the crew to distribute life preservers. There were two in my stateroom but on “E” deck it was absolutely impossible to reach them after the explosion from the position in which I stood, as the ship filled so rapidly. There seemed to be no surplus supply on the upper decks.

The starboard side was not very crowded with people when it became awash, and at this period I assisted quite a number of ladies into one of the boats which was afloat but still attached to the davits; after this boat was filled, with no men in it at all with the exception of two sailors in the bow and one in the stern, I jumped into the stern and endeavored to assist the sailor in releasing this chain and tackle, having noticed that the two sailors at the bow were endeavoring to do the same thing. We were absolutely unable to do anything with them with our hands, and there was no tool or hammer with which to knock the pins out which were holding the chain.

The ship at this time was continually sinking on the starboard side, and the sailors and myself still continued trying to release the boat from both the chain and the tackle until the davit reached the position of crushing the boat in the middle, and seeing there was no possible chance to get it clear, the sailor in the stern and myself stepped to the rail and dived overboard.

We swam as fast as possible towards the wreckage, fearing the funnels might fall but got well clear until as the ship rolled over on her starboard side I noticed the wireless descending through the air and was struck by it as it went down. The sea at this time was filled with wreckage of all kinds, dead bodies of all ages, many with life preservers on. My watch stopped at 2:19 Liverpool, and the ship went down an estimated 8 to 10 minutes after I left her.

Mr. Charles Lauriat, Jr. of Boston, Mass., with two sailors and myself swam to a collapsible boat which had been washed from the deck and climbed aboard. The two sailors cut the cover off, and then we began to pull people from the water until a total of 34 people were on this collapsible boat. Then we attempted to raise the sides but found that the iron work was broken and that while we could raise the sides we were unable to make them stay in position until we picked up some pieces of wreckage and placed it under the seats which held the sides up.

There were no oars in this boat although row-locks were provided, but this difficulty was overcome by picking up five oars floating about in the water. We then rowed away towards the only sail in sight, which was reached at about 4 o’clock. It proved to be the sailing trawler P.L. 12 of Glasgow, which took us aboard with many others, until she was accommodating all she could get on, and also took in tow two other boats and started for Queenstown Harbor.

At six o’clock we were taken off by the regular mail steamer belonging to the Cunard Line, out of Queenstown. We arrived at the wharf in Queenstown at exactly 9:30, and were kept waiting for twenty minutes before being permitted to land.

Detective Inspector William J. Pierpoint had crossed to New York on the Lusitania’s final completed voyage; his presence was commented on in several accounts of that trip. He and James Brooks were briefly in the same lifeboat. Detective Pierpont was one of several survivors who were sucked into the submerging funnels, and then expelled, as the liner heeled and recovered for the last time:

William John Pierpoint

Courtesy Wendy McCawley/Mike Poirier collection

The band in the dining room had just responded to an encore of “Tipperary” when the valet of an American millionaire passenger shouted “Look!” I looked through the window and saw the torpedo coming straight at the ship, and knew at once it could not escape. One seemed to stand spellbound and hopeless.

The torpedo must have been fired from a good distance, and it split the water aside as it rushed along, finding its true target. The explosion occurred almost immediately after the striking. No submarines were seen about, and while it has been said that a British cruiser had been in the vicinity, cannot say from my own observation what convoy was provided for the Lusitania.

Not once was there any panic onboard, though the liner began to sink down straightaway and we knew that she was doomed. Going to my stateroom for a lifebelt, soon found myself having to walk at a curious angle, but managed to get to one of the decks.

Some thirty or more people had been put into a lifeboat. I was the only one remaining onboard thereabout, and decided to jump in. then the Lusitania plunged and the lifeboat, being still attached to the davits, was pulled down into and under the water. What the fates of the thirty people were, I cannot tell. I know that I was under the surface a little time, and when I came up it was to find the top of one of the huge funnels coming at me.

It was a curious experience. What the precise sensation was, one could not describe. Somehow or other I regarded it all with a detached sort of feeling, as an outsider who is looking on at something extraordinary but is not in it himself. I was carried down the funnel, and then was shot up again, apparently by the rush of escaping air from the ship. Later on I discovered that another passenger went down that, or some other, funnel, and we both came up blackened with grease.

I drifted to an upturned boat and was pulled on to it by a steward. He [words omitted] were party of eight – not to count the body of a woman who did not survive her rescue very long – and we were taken off three hours later by a torpedo boat. The sea, strewn with the dead and the struggling living was an appalling sight. We had some trouble with a lady who was in our party of eight. She was violently sick, and then she became hysterical and had to be restrained from jumping off.

William Pierpoint died at age 86, in Liverpool, on May 8, 1950.

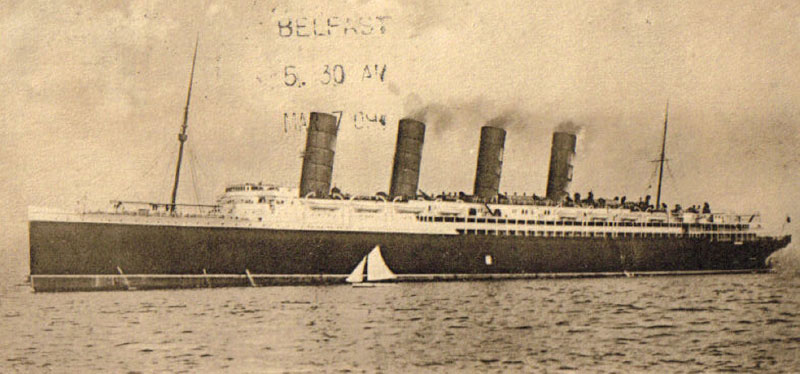

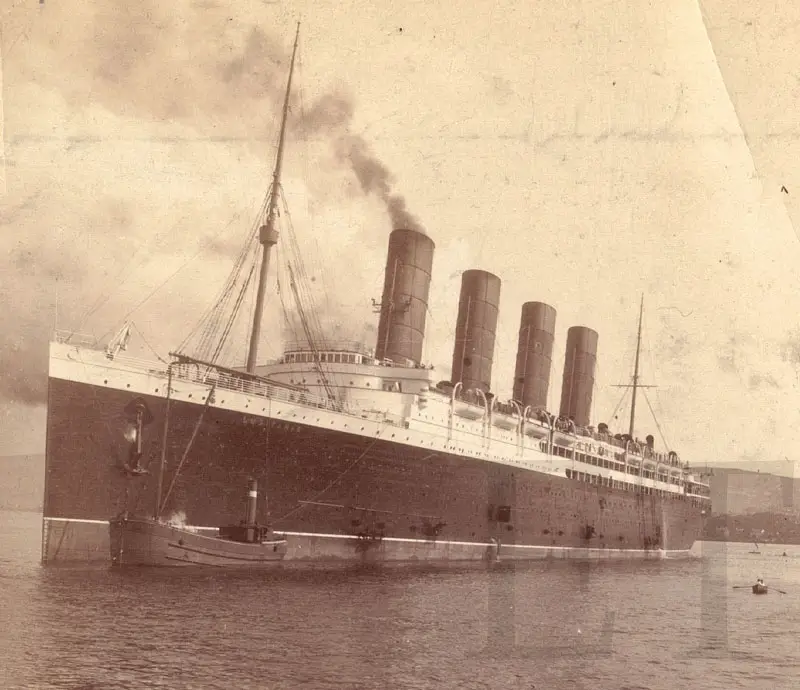

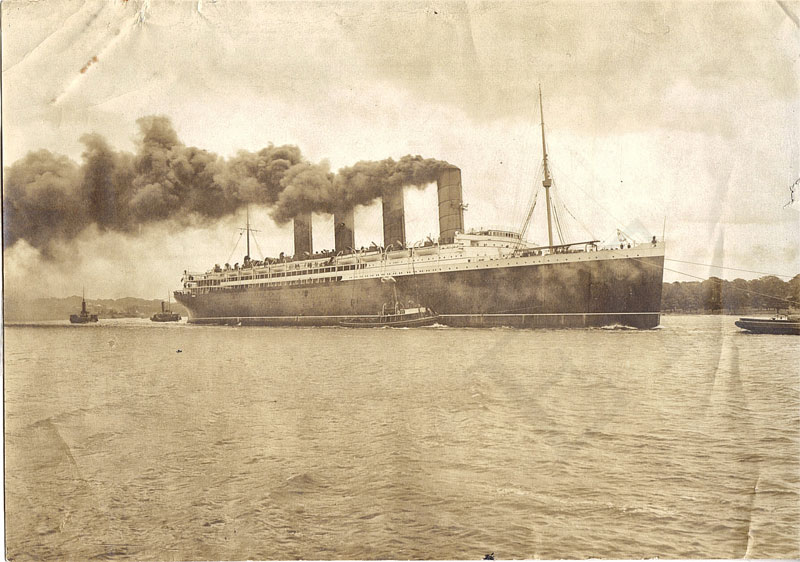

“To me she was my dream ship. I saw her first when in her regal beauty she sped along the surface of the Clyde upon her trials. My boyish heart went out to her in admiration.”

That was Albert Arthur Bestic‘s first impression upon seeing the new Lusitania. The next time he saw her, he was on a small windjammer. As he looked up at the liner, he saw, “a photographic impression of four big funnels, tiers of decks, fluttering handkerchiefs, the name Lusitania in gold letters, and a roaring bow wave.” When the ship “streaked by”, it created a large wave that sent all the men into the lee scuppers. The sailors began cursing at her, but not Bestic. He vowed one day that he would stand upon the bridge of that ship!

Albert Arthur Bestic

Bestic itself is not a name of Irish origin. The branch that Albert descended from was originally Huguenot French, from the Normandy region. He was the second child of Arthur and Sarah Bestic, born on August 26, 1890. He had an older sister, Olive, who was born in 1888. The family resided in Donnybrook, Dublin South. His father was a banker and a wood worker. He was educated at the Portsmouth Grammar School and the St. Andrew’s School.

The sea called to Bestic at an early age, and he joined the sailing ship, Denbigh Castle as an apprentice. It sailed from Cardiff, Wales for Peru. The ship had a treacherous crossing. The Denbigh Castle encountered many storms, and at one point a sailor on board said that Davy Jones had been “foiled again”. The ship was feared lost until it finally sailed into Fremantle, Australia and proceeded to its final destination of Peru. It had taken well over a year to get there. This did not deter Bestic and he continued to work his way up. He also became acquainted with Annie Queenie Elizabeth Kent, originally of Belfast but living in England. They continued their courtship and were married in early 1915.

He sailed to the US as an officer aboard the Leyland liner Californian. He was then informed, to his great surprise, that his next assignment would be as the Junior Third Officer of the Lusitania– his dream ship! Looking around at his new surroundings, he thought to himself, “Would not fate put me in command of her someday?”

Lusitania Officers

Left to right: Arthur Rowland Jones, Albert Bestic, John Idwal Lewis.

Quick introductions were made to his fellow officers. He found Staff Captain Jock Anderson friendly, and that put him at ease. First officer Arthur Rowland Jones, of Flintshire, had a grimappearance. His relaxation was perusing his five volumes by Conrad in his cabin. Percy Hefford, like Bestic, had recently been married. Bestic was advised to avoid socializing too much with the passengers, especially the ladies.

The boat drill was held but, as he later noted, his lifeboats were not lowered because a coal barge was directly underneath them.

Junior Third Officer Bestic settled into his duties once the ship sailed. These included his watches on the bridge, completing meteorological forms, the log book, late night tours with Hefford, and baggage room detail, which he detested.. His preferred off duty activity was playing bridge in the officer’s smoke room with whichever officers might be available. He remembered one game being interrupted by a knock on the door.

“The quartermaster appeared at the door with a four-stranded Turk’s Head in his hand. ‘Captain’s compliments and he says he wants another of these made.’ The bridge had to be stopped and we spent the rest… trying to remember how it was made.”

One night before the disaster always stuck out in his memory.

“Looking into the ballroom where dancing and gaiety held sway, my thoughts flew to that famous dance given by the Duchess of Richmond in Brussels on the eve of Waterloo… I still wonder if it was a premonition of disaster.”

He was on the 8-to-12 watch on May 7th, and took the soundings due to the intense fog. He also telephoned down about the fire drill. Ex-Chief Stevens then took his place, and Bestic left and had his lunch at 1 o’clock, as he always did. Baggage master Crank came to him soon after and informed him that, “he was about to get the baggage on deck preparatory for discharge on our arrival at Liverpool, and that already a working party awaited my arrival.” Realizing that he was in his good uniform, he went back to change into his old one that he used for such work. He had just finished changing, and was in the officer’s smoke room, when the Lusitaniawas struck.

“I heard an explosion… and went out on the bridge and I saw the track of the torpedo. It seemed to be fired in line with the bridge and it seemed to strike the ship between the second and third funnels as far as I could see… the possibility of the Lusitania being doomed never entered my head. A crippled engine maybe, followed by a limp into Queenstown would be, to my mind, the climax of disaster. Then inexorably, the facts were forced into my brain. The heavy list, the settling down by the bows… I heard the order, ‘hard-a-starboard’ and I heard Captain Turner saying, ‘lower the boats down to the level of the rail’ and I went to my section of boats… My section was from 2 to 10.”

Researchers have relied on a book that purports to quote Bestic as saying that the list caused the lifeboats on the port side to drop onto the deck and slide down towards the bow, supposedly leaving a trail of broken and bloodied bodies in their wake. However, reading through Bestic’s testimony and the many accounts that he wrote, we found no evidence that he ever said such a thing. Whether he stated this in his unpublished and now lost manuscript, Waveswept, or authors added this detail to his story is unclear.

Staff Captain Anderson was by Bestic’s side trying to assist in getting the boats away. They were trying to lower boat 10, but it didn’t quite make it over the side of the deck.

Captain Anderson was beside me and he said, ‘Go to the bridge and tell them they are to trim her with the port tanks.’ I made my way to the bridge and sung out that order to Mr. Hefford, the second officer. He repeated it and came back again and no. 10 boat was on the deck. We tried to push it out but could not.

He later noted that when trying to lower the port boats they would scrape down the side of the “sloping hull” rendering them unseaworthy.

Looking over the side, he saw that the boat deck was only a few feet above water. He stepped over the side, with no lifebelt, and began swimming away. He found him self being drawn down in a “hole” in the ocean. He was going downward in the whirlpool. Finally, he felt the suction cease, and he began his swim upwards. He broke the surface, but was briefly pulled back down again by a drowning person. The next time he came up he cracked his head. Unable to see, he wondered if he was blind, but soon realized he was underneath an upturned boat. Diving downwards, he came up alongside the boat and was pulled in by a crewman named Quinn. No sooner did he began to get his bearings, he realized many people were trying to clamber aboard. The craft was in danger of sinking, so he took to the water again. Using a side stroke, he took off and swam right into a collapsible. It was awash, but nearby he found some floating water tanks to help the buoyancy of his refuge. “I knew I was saved.”

He helped rescue other people from the water and a few hours later was picked up by the trawler Bluebell. He soon found himself face-to-face with Captain Turner. Their encounter was brief and the officer congratulated his captain on his escape. Turner, in his gruff way, turned to Bestic, whom he always called “Bisset,” said, “You aren’t that fond of me.”

Bestic was back in his native Ireland, but under tragic circumstances. His stay was short, and soon he was back in England preparing for his testimony before Lord Mersey. He was questioned on the seaworthiness of the lifeboats. He testified that he checked the gear, but that he was unaware of the condition of the boats themselves.

A year after the sinking, his wife gave birth to their first child, Desmond Arthur. The war was raging and Bestic was serving in the Royal Navy aboard minesweepers. He suffered losses when his mother died in 1917, and his sister ran away with a boy she met at college when both families disapproved of the match. They disappeared without a trace, much to his regret. His second son, George Stephenson, was born in Scotland in 1919.

Bestic’s career at sea continued, and he served as the captain of several relief vessels with the Commissioners of Irish Lights. His last child, Alan Kent was born in 1922 in Richmond. The Lusitania was never far from his mind and in 1932, the Railey expedition contacted him to join them to explore the wreck. Unfortunately, the expedition never went anywhere.

A few years later, Captain Henry Russell financed by the Argonaut Corporation invited him and fellow survivor Robert Chisholm to join him in exploring the wreck. He joined the expedition as chief officer aboard the ship, Orphir. He noted there would be a number of false trails, but he was confident that Lusitania would be located using Cunard data, Captain Turner’s notes and his own memories. They were using a new Marconi detecting device that would aid them in finding her. He predicted that because the ship would be on its side, it would be somewhat flattened due to pressure. The Orphir encountered such a horrific storm that Bestic ordered the wireless operator to prepare to send a message. Visibility was non-existent and green waves washed over the decks. The wind whipped through the mast and roared down the ventilators. The former Lusitania officer was in charge of the port side boats, just as he had been twenty years before. He ordered his crew to stand-by. Heading back to Kinsale, they had a near collision with a Dutch boat, Parnevele, when it crossed the Orphir’s bows.

The expedition divers would be Jim Jarrett and Ernest Pope. A reporter on board the expedition, Gilbert McAllister, described the diving gear as “weirder than Frankenstein”. The reports from the expedition fascinated people. Survivor Robert Timmis was now blind, but listened to daily radio reports of the expedition while, Lady Rhondda declared she would like to dive to the Lusitania herself.

A barrister named James Burke was interviewed, for he had seen the Lusitania sink from the shore. His roommate at University College, Cork, was the Lusitania’s Dr. McDermott, who was drowned. Burke added the curious detail that the locals refused to eat fish for over a year as the fish had been feedingoff the Lusitania victims.

The expedition turned perilous as Jim Jarrett was diving. An anchor was caught by the currents and flung against his suit, just missing the glass of his helmet. He was raised back to the surface after his near-death experience, but soon asked to try again. Sadly, in the midst of the expedition, the owners fired Bestic, for he refused to give up his book rights. He went ashore in September of 1935.

The ship was found in October. The new chief officer, Horn, requested that the Orphir range 500 yards out of its limits, “just for luck”. The able seaman at the helm soon shouted, “There’s something Sir.” The graph showed an outline of a large shipwreck.

Jarrett finally dove to the wreck. He saw little due to limited visibility, but had the remarkable experience of walking across the liner’s “slime covered plates”. Although the ship had been located, dreams of finding and recovering the gold supposedly aboard the sunken vessel were unrealistic and the expedition was soon ended.

Bestic kept himself busy, and in an exclusive interview he conducted for the New York Times, he talked with Captain William Turner about their experiences aboard the Lusitania. Bestic asked Turner if he thought the ship would be torpedoed.

Yes, I was distinctly worried. I was advised by the Admiralty that I was to keep a mid-channel course. As you remember, we were warned by wireless that there were six submarines waiting for us in mid-channel. That was the chief reason I closed in on the coast. I thought that if the ship were sunk near shore, the top deck might be above water, allowing the passengers to escape… I am certain she was struck twice.

The former officer, turned journalist, asked about the rumor of gold aboard. Turner replied,

No gold of course, but there must be a lot of money and jewelry in the purser’s safes. I am quite sure of that.

He chuckled about his own property left aboard the ship.

There are 15 (British pounds) that belong to me. That is all. But there is an old sextant I value. It’s in the left hand drawer of my desk on that ship.

Bestic found his former commander to have the same “alertness of manner and the same quick penetrating look in his sharp blue eyes. But his quarterdeck manner had softened considerably.” He also wrote that Turner said he was “distinctly worried” about being torpedoed on that voyage. Bestic made the error of saying in the article that he was the only surviving officer. This prompted a newspaper rebuttal by the senior third officer, John Idwal Lewis.

A final disaster nearly killed Bestic. He was serving as commander aboard the Light ship Isolda when she was bombed and sunk in December 1940. Six men were killed. Poor vision and a touch of heart trouble forced him to retire from the sea and he found himself writing more articles as a new career. He helped Adolph Hoehling with certain details of the 1915 shipwreck, for a book called The Last Voyage of the Lusitania. His own book about his adventures aboard the Denbigh Castle, called Kicking Canvas was published a few years later and was well received. He now lived in Bray and was considered a local authority on the sea.

Bestic wrote an article about the documentary film of the Light expedition to the Lusitania. The article became a reunion between several survivors, some of whom Bestic had not seen since 1915. It was entitled, So I Shall See the Lusitania Again. He was finally able to see footage of his lost “dream ship.” Bestic took ill as Christmas time approached, and passed away on December 20, 1962. He was buried in family vault in St. Michan’s Parish Church in Dublin.

John Idwal Lewis…

John Idwal Lewis started his sea-faring career in sail. The native of Portmadoc, North Wales was first signed aboard a three-masted bark He later remembered receiving a daily ration of a pound and a pint- eight ounces of butter, marmalade and sugar, and a pint of lime juice to ward off scurvy; but he never complained. Since he was slender and only stood about 5’6 in height, it was easy for him to work in tight places.

He finally went to sea, “in steam,” as he put it, on the Moss Line, and the Blue Funnel Line, in 1912. The following year, he earned his master’s certificate. He joined Cunard in September 1914 as intermediate third officer and a month later he was assigned to the Lusitania, and he would remain with her until the end.

Recalling his duties, he stated:

“There is a daily inspection on all the ships that I have been in this line, at half past ten. I used to attend on them everyday. I attended the whole of the ship, there was six of us going on this inspection; the staff captain in full charge, the senior surgeon, the assistant surgeon, the purser, the chief steward and myself. It was to begin at half past ten outside the purser’s office on B deck. Then we would start to go all around the passengers’ rooms; we would inspect a room here and there, all the bath rooms, boilers and alleyways, and see that everything was clean and in order, and go right around each deck right down to the saloons and the galleys down to the steerage; the same thing in the crew’s quarters and the firemen’s quarters.”

He continued

We were all together and met on B deck. We all went together through the B deck section right fore and aft, and down to C deck, and the same thing through C deck, and then we all went down to D deck, and there we divided forces…

The staff captain and the assistant surgeon and myself went through the forward end of the ship, through the sailors’ quarters and the third-class and steerage quarters and the stewards’ quarters forward and the store room, and we came along up C deck and went down through the third class entrance and followed the other route through the saloons and kitchens up into the second cabin and met outside the second cabin entrance of C deck, and we went along and went down into the firemen’s’ and trimmers’ quarters which had the entrance on C deck; we went down there.

After we finished there, we used to pump back again and go up to A deck in through the verandah café and the smoking room and the house, and were dismissed when we got outside.

The Lusitania’s appearance on the final voyage made a strong impression on John Idwal Lewis. When asked, he would say, “A black hull, black funnels.” He was not the only one to describe the ship as having been re-painted from the traditional Cunard colors. Thomas Slidell described the funnels as “giant gray tubes.” Sarah Lund, in her charges against Cunard, claimed that the superstructure was painted gray. Lewis would disagree, while testifying on behalf of the company, and say that superstructure itself was still white.

Sailing day was especially busy and Lewis had to make sure several tasks were carried out.

The morning we left Liverpool we had a Board of Trade mustering drill just before we sailed, under the supervision of the Board of Trade Supervisors; just to muster all hands and all the ship’s members and swing the boats out on both sides, and swing them inboard again.

He was in charge of the starboard side during the drill, boats 1 to 11, which was next to the quayside, and his boats could not be put in the water. He was not sure if the boats in the port side were rowed in the river. Crew members were assigned a certain boat when they signed on, receiving, “a metal badge with the number of a boat on it.” Boat lists were also provided on the ship. “The names of all the crew put outside their boats. The boat list is a paper and the diagrams for the boats on the port and starboard side with the names of the crew. If I remember rightly, there were three posted aboard the ship. They would be in the living quarters of the different staff for instance where the stewards have their quarters; they would be even down to the glory hole facing them and you cannot mistake them going downstairs.” They were also “in the firemen and sailors quarters… Each officer had a book with the name of the boat, corresponding to the sheets.”

The Lusitania was ready to sail, following the transfer of passengers and crew from the Cameronia, whose voyage was cancelled when she was requisitioned for naval service. Lewis remembered years later, on a television appearance, that he looked out and saw a woman running along the dock. “I saw the gang plank being raised and then lowered again… I happened to be the mail officer on the ship and just when coming on board, after checking the mail, a shout came from the shore, ‘Wait! Wait a minute! Wait a minute!’ And I happened to turn around and saw a lady coming up the gang plank.” He said he later learned that it was Alice Middleton.

Lewis may have become familiar with the stories of the crew members with whom he came in contact, as the voyage progressed. Staff Captain Jock Anderson had his nephew, George Edward Latham, aboard as an electrician. Second purser Percy Draper’s wife was expecting a child, the birth of which was expected to coincide with his return to England. Albert Bestic, the junior third officer, was to have joined the Leyland Line for his first ship assignment as an officer, but was transferred to the Lusitania. Second officer Percy Hefford, a graduate of the famous Rugby School, had married three months earlier. Extra chief officer John Stevens had recently received word, while chief officer of the Cephalonia, that his wife had died. He had to complete another voyage on the ship and then he was allowed to return home- on the Lusitania. Stevens was lost on May 7th, as were Latham, Anderson and Hefford.

There were daily boat drills, but not for the passengers:

Q. Had there been any boat drills during the voyage, prior to May 6th?

A. Yes, an emergency drill… Well, we have two special boats in the ship that are always at sea swung out… I think they were 13 and 14; I am not absolutely certain; we used to have special wire guys spread out between the two davits with a life line attached to these reaching down to the water’s edge. Every morning, or usually every morning the whistle would go and these men went back to muster at the emergency boat. Whichever side of the ship was the lee side. There was a picked crew from the watch… Then after these fellows would stand at attention in front of the boats and I would say, “Man the boats,” and these men would get into the boats and put their life belts on and sit in the number of their place in the boat. After I saw that everything was all correct, I would dismiss them from the boats. This was done under my supervision, daily.

Q. Let us go back a moment, and tell us what the signal for the emergency drill was?

A. The steamer’s siren; they used the blow the steam whistle… a long blast and a series of short blasts.

Q. What did the pursers and stewards have to do at this drill?

A. The pursers look after the ship’s papers and the stewards attend to provisions, and so forth, and were attending to blankets and there were the stretcher guard, the ambulance guard. The lifeboats were readied on the morning of May 6, as the ship approached the war zone.

Q. When the boats hang in the davits with these short chains on them how high up are they above the deck?

A. Well, they should be–the boat should be about 8 feet from the deck.

Q. Could anybody get into them at all?

A. Well, I suppose I could if I jumped.

Q. And when the boats were swung out the morning of May 6th, you say they were lowered down to be on a level with the collapsible boats?

A. Yes.

Q. How high would that bring them down above the deck?

A. The collapsible boats would be about 3 feet–about five feet; you have to go over the collapsible boat to get into the lifeboat. The lifeboat was not lowered to the level of the deck, but to the collapsible boat; just a matter of 2 feet.

Q. Could the lifeboat be lowered after that was swing out, to be level with the collapsible boats, with out disengaging these chains to which they were hung in the rocker?

A. Impossible.

Q. Won’t you describe the collapsible boats?

A. A collapsible boat is something similar to a life raft, rather flat bottomed, it only raises about 18 inches from the deck… just like an ordinary (boat)–two bows on it and wider in the beam and flat bottoms. The wooden part of the boat is only about 18 inches deep… Decked over, watertight tanks, inside. Above that there is canvas sides that you raise up, like opening a concertina, fixed up with iron bars to raise the seats up.

Lewis testified that “All the ports were to be closed and not only that, all the windows at night were to be closed and darkened and all the doors leading to the decks were to be closed at night.” Lewis was careful with his wording while testifying, lest he be contradicted by other witnesses:

Q. Were any ports open, so far as you know?

A. No, not as far as I am aware of it, no.

Q. On the day of the accident

A. As far as I am aware of it, no.

Q. Of course, you were not in any passenger’s staterooms to notice the ports?

A. No.

Q. But the ports in the alleyways and in the places you were in were in what condition?

A. They were closed, all those ports; one or two of these might be open on C deck. They open on to the shelter deck; there were men detailed every morning to clean the brass work on those ports, because they open on to the third class passengers’ promenade deck and there are two men specially detailed off to clean the brass, and probably they were cleaning them at the time, and there might have been one or two open, but if any water came in there it would go down the wooden deck and would run out through the scuppers.

Q. Did you attend on the night inspection of May 6th?

A. Yes, I did

Q. At what time?

A. From about half-past eight until ten o’clock

Q. What was the condition of the ports that night?

A. They were closed as far as I could see; some places of course I couldn’t go.

Q. To what do you refer?

A. I refer to some of the staterooms of the passengers.

Q. Had there been orders to have all ports darkened?

A. Oh, yes

Q. Were you running without lights?

A. We were.

Lewis had an unenviable shift the day of the sinking. “I was on from 4 to 8 in the morning… on the bridge… with the chief officer… I remember that when I went on watch in the morning that I had my overcoat on and was glad of it too. Yes it was foggy.”

He had a quick breakfast, and from there was off to the baggage room:

Q. Where was the baggage room, by the way?

A. It was down – the entrance is on C deck, it is right in the bottom of the ship.

Q. Were you down there continuously, or were you up and down?

A. I was going up and down.

Q. Were you on deck at all?

A. I was out on deck, on C deck

Q. On the side, so you could see the condition of the weather?

A. Oh, yes, you could see all around… It was, as far as I can recall it, foggy all morning.

Q. What was the conditions of things then, as far as being able to sight the land was concerned?

A. Well, the weather was clear, but hazy over the land… I could see land all right, but I didn’t take too many particular notice what it was; I knew were we out to be, so I guessed where we were.

He finished his duties about quarter of one, and proceeded to his cabin to change for lunch. He was going to join first officer Arthur Rowland Jones in the first class dining room. His table was “on the port side… the after table of all on the portside… It was right from the side of the ship, right to the door of the grill room, to the entrance of the grill room, a square table.”

Q. Did you notice anything about the ports in the dining room while you were having your lunch?

A. No, they were shut on my side, as far as I could see.

Several passengers in the dining room contradicted Lewis. James Brooks:

On my left, I sat facing the bow and very near the entrance on the left of that section of the dining room that was all open. That would be just the same as these windows are here, and I sat on the port side of the center line at the dining table; they were open on that side. Rita Jolivet: They were open. Frederic Gauntlett: Nearly all were open…Well, I left my coffee and nuts and rose from the table and shouted to the stewards to close the ports. Oscar Grab: I noticed that they were open. Charles Lauriat: Yes, because there was an electric fan right over my head, and with the portholes open, the draft and the fans going at the same time made it very drafty. Isaac Lehmann: It was a beautiful day and all the portholes were open.

Lewis was finishing his lunch when there was an explosion: “I should say it was just like a report of a heavy gun about two or three miles away from us.”

Q. From what point on the ship did it appear to come?

A. From the fore part of me on the starboard side. A few seconds afterwards, whether it was an explosion or not I couldn’t say, but there was a heavy report and a rumbling noise like a clap of thunder… It was accompanied by the sound of broken glass, like glass breaking. That was on the starboard side again, forward of me, but closer than the first one was, further aft than the first one. I stood up and looked around and both of us walked out of the saloon. Of course, we couldn’t run out, there were too many people ahead of us.

The ship began listing immediately:

I should think it would be about 10 degrees when I was on the staircase. I went up along the main saloon staircase up to C deck. The only difficulty was that the place was crowded with people ahead of me. I came out on to the C deck on the port side and went up on the boat deck along the outside ladders, the outside staircases.

One of the first people he saw was Mr. Piper, the chief officer, standing by No. 2 boat:

Q. Had the ship begun to swing over toward the land yet?

A. She must have, because when I went over on to my own station I could see the land.

Lewis went to the bridge, where he found the quartermaster. “I sang out to the quartermaster and I said, ‘What is the list on the telltale, on the compass,’ and he told me 15 degrees.” He had no lifebelt. Percy Hefford, the second officer, had thrown him several from the bridge, but he gave them to other people.

He went to his station, boats 1-11 and found Mr. Jones there, on the starboard side, as well. One of the first things he noticed was that lifeboat 1 “was lowered into the water before I got up there, but the tackles were fast to it, the after fall was a bit tighter than the other one, so the boat was heading out to sea and had been drawn sideways along the ship, but it was floating in the water.” There were two sailors in it. He did his best to fill the boats in his section, but almost none got away. “Well, filled them up with passengers, with people; I don’t know whether they were passengers – I filled it up and lowered it down… The list of the ship would swing the boat out from the edge of the ship… When we had taken the women passengers on to the edge of the collapsible boat to get into it the distance was such that they rather drew back instead of getting in it; we had to use our best judgment to try and get them into the boat. Some were afraid of attempting to go across.”

Q. How many people do you think were in?

A. Well, it was loaded, as far as I could see, full; of course, I didn’t stop to count them; I ordered them to lower away and it was lowered away… I saw it unhooked and settle in the water. When I was standing on the deck I saw a fishing schooner way over inside, and was looking at that and wishing it was a bit nearer, and I could swim for her, but I could see the land too and was wondering how I could make it.

Not everyone was cooperative:

When I was getting one boat out, I forget the number, I was standing on top of the collapsible boat seeing it lowered down and it was full up and these fellows when they saw the boat being lowered tried to rush it. Of course, I had to stop them.” He made his way down the deck to work on the forward boats, and was opposite the first class entrance: “I filled that boat; I saw that they started with the filling that boat, because when they were getting well under way there, I went further aft again and saw Mr. Jones and I said, ‘I had better give you a hand there, because they are filling mine up here,’ and that was one of the boats that he and I lowered. He took charge of one and I took charge of the other end, so that these people were lowered down properly.

Following that, he claimed that he went back to his own section. “I was continuously between no 1. and no 9. after that, going from one to the other, seeing that they were going all right.”

Q. Did you get 9 down safely?

A. It was lowered into the water safely.

Q. And unhooked

A. And unhooked.

Q. And away?

A. Well, whether it drew away from the ship’s side, that was something I don’t know. I didn’t see it exactly going out, but I saw it in the water. I simply gave orders and said, “All right” and when the boat was in the water I said, “Get out with her.” A lady passenger was in the boat there, and I was standing on the deck and the boat was just away from the ship’s side and screwed up, and she stood up and sang out, “For God’s sake jump.” I looked at her and said, “Good-bye and Good luck. I will meet you in Queenstown.”

Working back and forth, the last boat he went to was 3. He said there were very few people left on the deck.

Q. Were they able to stand up?

A. No, not without hanging on to a bit of the hand rail on top of one of the houses; in fact, it took all I could to stand on the deck.

Looking about he saw:

“the water was on the bridge deck and rising fast; I made an attempt to go aft and missed my footing, but I got hold of a collapsible boat…… I was standing up to me knees in water, practically.”

To his surprise, he spotted a tiny gold watch, no bigger than the size of a quarter being swept along the deck by the water. He reached down and pocketed it.

I fell in the water on the deck and got hold of the collapsible boat and scrambled on it and got hold of the rail on the funnel deck or hurricane deck, and got over there and tried to make my way across to the port side to take a dive off, but I was just about half way across when she went down under me.

Q. When the ship went down were you drawn under?

A. I must have been, because I didn’t see anything of the ship and I was in the fore end of her; when I came up to the surface there was no sign of the ship at all.

He grasped a piece of a boat chock when he rose to the surface:

“Sometimes I was on top and sometimes I was underneath it, and eventually I got alongside of a collapsible boat that was just floating stem up, about one-third of the boat sticking out of the water, and I got on top of that and was there half an hour when a trawler picked me up.”

He landed in Queenstown, and left the next afternoon for England. He gave several sets of testimony during the Liability hearings. The fact that so few of the boats got away did not escape the lawyers:

Q. I notice in the book that Mr. Lauriat wrote, I believe it was written while he was there in Great Britain after the disaster, he says (page 49): He speaks of seeing in the slip six lifeboats, inside the wharf at Queenstown. He mentions the numbers 1, 11, 13, 15, 19, and 21; did you notice at any time notice the numbers of the boats after you got to Queenstown, the ones that were brought in?

A. I never saw them in Queenstown.

Q. Do you, yourself, know how many lifeboats you actually got away from the ship with passengers?

A. No.

John Idwal Lewis remained with Cunard after the disaster. He rose, during the war, to the position of chief officer; one of his ships being the Carpathia. He eventually attained the rank of Captain, and then was made the assistant marine superintendent of the Cunard White Star Line.

He married a woman named Sophia and had two children, Henry and Joan. He made his home in New York and vacationed in Inverness, Florida. He was a member of the Pyramic Lodge, number 490, of New York City.

Lewis came across a newspaper interview that fellow officer Albert Bestic conducted with Captain Turner, and was miffed that Bestic assumed he was dead. Bestic wrote, “I am the only surviving deck officer of the Lusitania and with the anniversary of the great liner’s loss arriving, it occurred to me to go to Liverpool to see my old commander and find out how he was faring.” Captain Turner was described as alertand made several interesting statements.

Lewis’s rebuttal came a few days later:

I was third officer of that ship and standing by my station amidships, when she heeled to starboard and went down bow first. We managed to launch 6 lifeboats in which 700 person were saved. Three deck officers were saved besides Captain Turner. A.R. Jones, the first officer who was drowned later in the war, and Bestic, a young Irishman from Dublin, who was making his first trip in the Cunard Line – I think it was his last, because I never heard of him afterward. He was the junior third officer.”

John Lewis had a reunion with several fellow crew members on the 20th anniversary of the disaster. It was held in his office at the New York Cunard White Star building. He met with Richard Wylie, assistant marine engineer of the line, and William Ewart Gladstone Jones, chief electrical engineer of the Scythia. Alexander Duncan, Chief Officer of the Berengaria, and Charles Dunn, Chief Engineer of the Bantria joined them later. They planned on drinking a silent toast to all their shipmates who went down with the Lusitania.

He retired in 1950 and moved to California in 1956, as both of his children lived there. He settled in Stockton in 1960. The “short, taciturn” sailor spent his time sketching ships and working in his garden. Towards the end of his life, he suffered from illness and in his last year, stayed in the Lodi Convalescent Home.

John Idwal Lewis, the last surviving officer from the Lusitania‘s final voyage, died on October 21, 1974.

One interesting piece of Lusitania history, preserved on kinescope, is a fall 1955 appearance by John Idwal Lewis on the American television show This Is Your Life. The format of the show was simple: a celebrity and a lesser known person would each be given a segment in which the host told their life stories and reunited them with long-forgotten figures from their past. Milton Berle and Alice Middleton, Lusitania survivor each had a segment on the episode.

It is interesting viewing for a vintage TV buff, but frustrating for a Lusitania researcher. Berle’s segment ran overtime, and so Miss Middleton was given very little chance to speak during hers. Where normally she would have told her Lusitania experiences in the first person, Ralph Edwards, the show’s host, faced with a very limited amount of airtime, instead told her tale at a staccato pace, allowing her brief time to comment:

(Paraphrased)

MIDDLETON: Yes.

EDWARDS And, do you recall that when you came to the surface you witnessed many terrifying things before finally, mercifully, losing consciousness?”

MIDDLETON Yes.

However, the show is not without its surprises. For one thing, it reveals that Middleton was not a Red Cross nurse, as other accounts state, but instead a nurse in the child-rearing sense: she was reunited on camera with the children for whom she cared in 1914-1915. It offers filmed greetings from the Irish doctor who saved Alice’s life, who was present when she was nicknamed “Marvel” for her survival. And, best of all, it offers an appearance by John Idwal Lewis, who is actually given more time to speak on camera than Alice Middleton!

Lewis seems at ease, has a distinguished speaking voice, and confirms that Alice Middleton was the woman who dashed up the gangplank at the last second on May 1st, 1915. The show ends with Alice Middleton being given a diamond necklace and a brand new 1956 Mercury automobile, as well as a kinescope of her appearance and a sound film projector on which to show it. It was through the courtesy of Alice Middleton’s family that we were allowed to view This Is Your Life Alice Middleton, from her own print of the show, and get to see John Idwal Lewis in person.”

William McMillan Adams, 19, of New York and London, was traveling in first class, with his father Arthur Henry Adams, 46.

I am an American; my address in England is 5 Cumberland Terrace, Regent’s Park, N.W.

I was traveling with my father. He was lost. Our births were first-class D37 and 45 on the starboard (side).

I was up in the lounge at the time of the explosion. I rushed up into the hallway and looked out to sea on the starboard side. The water was pouring down from the water chute. As I was standing there, there was a big shock. I thought the mast or something had fallen down. A man passed me who said he had seen a torpedo.

My father came up and met me. We went over to the port side on the upper deck and started to try and launch the boats. All the men were trying to push these boats over. We did not succeed.

I saw two boats launched on the port side- both unsuccessfully. The first boat fell absolutely the whole distance. The man let go of the ropes and it crashed down. I know one of the survivors who is still at Dublin- Mr. Ogden H. Hammond. The other lifeboat fell in quite the same manner.

Finding that owing to the list on the vessel we were unable to launch any boats on the port side, I said to my father “We shall have to swim for it and we had better go down and get our lifebelts.” We went down to D deck, but could get no further than the stairs, for the water was pouring in all the portholes on the starboard side. It was impossible to get to my cabin.

Arthur Henry Adams and William McMillan Adams

We had some difficulty in climbing upstairs again, but we got to B deck. We went into every cabin on B deck trying to get lifebelts. I got one, but my father could not get one.

We saw they were launching a boat on the starboard side. We went up, and got all the women in sight into the boat. We then jumped into the boat and they stared to lower it. They lowered it very well, until we were about twelve feet above the water, when we fell. As the Lusitania was going forward, the boat filled with water at once. There was way on the ship at the time. Deck was then level with he water.

My father looked up and saw that the ship was going to fall over on us.

Next I found myself in the water, I came to a collapsible boat, quite empty and in perfect condition. I got half on to it, but could move no further either way. The mast came down and severely grazed my nose and face, and went straight through the boat just like paper, and put me down again.

I imagine a great many people were killed by things falling off the deck. I do not think many people knew the Lusitania actually went over on its side.

I got hold of a plank, then I swam to another piece of wreckage, a big box; and after about three quarters of an hour I came to an upturned collapsible boat with about ten people on it. They pulled me on. Then we were afterwards taken on to a collapsible boat full of water. We managed to bail this out, and we picked up something like forty people. Most of them were practically incapable of any work. We fished buckets out of the sea and bailed the boat out with them. We did not find anything in the boat to bail out with, but the boat was full of water. We rowed to a fishing smack, and we put the women and men who were very bad into the boat she was towing.

By this time, about six o’clock, the whole sea seemed full of tugs and torpedo boats. I reached Queenstown about 10:30. There were others before us; other oats passed us on the way to Queenstown.

My watch stopped at twenty-five minutes past two, when the boat went down.

Staff Captain Anderson said “Do not lower the boats,” and “Clear the decks.” It really rested with the passengers to find their way to the boats. It was the stokers who let down our boats, and I saw stokers letting down other boats.

People kept their heads. There was no panic.

When I was in the water shortly after the ship sank, about three quarters of an hour after, there were sixteen boats in sight of any type or description, all from the Lusitania; but no ships came up to rescue us until about two and a half or three hours.

There had been some fog in the morning; I was awakened by the fog horn about six o’clock. There was bad fog still at eight o’clock. The fog lifted at about 10:30. After that it was brilliantly fine.

In my opinion the ship was going slower than usual. I noticed there was very little vibration.

I saw no guns aboard the Lusitania.

I heard we were carrying shell cases.

The Missouri Historical Society has a memorial card, commemorating Arthur Henry Adams, in its archive:

Mrs. Harry Adams and Mr. William McM. Adams

announce with deepest sorrow

the foul murder of their husband and father

Arthur Henry Adams

on the

“Lusitania” Friday, May 7th, 1915

By order of the German Emperor

“The bloodthirsty hate the upright

But the just seeketh his soul.”

William McMillan Adams died in Princeton, New Jersey, on May 10, 1986

James Sidney Arter was one of several Lusitania passengers to have commenced their journey home with a transpacific crossing. He arrived in Seattle aboard the Aki Maru on April 23rd, and boarded the Lusitania eight days later, as the final major leg of his trip home to Mosseley, England:

Mr. Arter stated that he was just finishing lunch when the liner was torpedoed. A muffled explosion was followed by the ship taking an immediate list. Everyone hastened to their cabins to get the life saving jackets, but he saw no signs of panic.

Mr. Arter was lowered from the sinking ship in a boat, in which he stood up, being let down from a height of 80 or 90 feet on the port side. As there was not sufficient room in the boat for all, he dropped off into the sea wearing his life saving jacket, and managed to keep afloat for about an hour before scrambling on to a capsized boat. He was only 15 or 20 feet from the stern of the Lusitania when the latter disappeared under the waves.

A number of other people were on the overturned boat which he eventually reached, and three hours later they were picked up by a rescue boat. Mr. Arter did not see any submarine, but he heard of passengers who caught a glimpse of the enemy craft.

Mr. Arter has been abroad for some years, and was returning on the Lusitania for a holiday with his relatives in Mosseley. He is little the worse for his trying adventures, and stated that before the submarine attacked the liner the voyage had been a pleasant one.

James Sidney Arter died in the Federated Malay States on August 18th, 1932, at age 47.

Maitland Kempson, 55, of Birmingham, was returning from a business trip to the United States and Canada when he survived the sinking of the Lusitania. He was the director of the carpet manufacturing firm Mssrs. Woodward, Grosvernor and Co., LTD., and traveled in first class.

Along with three friends I was at lunch about a quarter past two on Friday afternoon and was just finishing when the liner was struck by the first torpedo. Of course, we all knew immediately what had happened. It was a frightful crack, like a crack of metal and metal, and the huge liner after giving a sort of a quiver immediately started to list. We all rushed to the staterooms for the life preservers…and as I was descending the staircase [ascending the staircase?] the vessel had listed to such an extent that it was almost impossible to get along. I was bumped first against one side and then the other.

When I got to the boat deck passengers were hurrying towards the sides. The deck was crowded with men, women and children. There was no real panic as far as I could see, but many of the women and children were crying. There was a whole crowd of women at one end and by this time the boat had listed over ore than ever.

I saw there was no chance of the liner floating and new that in a very short time she would go down, therefore I decided to look after myself by taking my chance. The lifebelt was around me and I jumped off the deck into the water, a distance of thirty feet. I swam for a little distance away from the liner and clambered in to one of the lifeboats with the assistance of some men.

The boat filled immediately; in fact, it was overcrowded and capsized and I found myself in the water again. I managed to swim about, and then I saw one of the collapsible boats a short distance away containing several survivors, and I struck out for it.

I looked round and saw half of one of the huge funnels which appeared as if it was going to fall on the little boat, but fortunately it did not. Passengers were struggling in the water all round, and we pulled as many into the boat as we could.

In the course of a very short time the great vessel heeled over and disappeared from view. She sank without any fuss whatever, as quietly as possible and there did not appear to be any suction, which we all feared as we were too close to her. When she had gone down there was, I think, and explosion, because there was a great rush of water and the people and boats seemed to be pushed away from where the last of the liner was seen.

We sighted a raft, and as our boat was so crowded and just level with the surface of the water we thought the best thing to do would be to make for it. We did, and lashed it to the boat and then we fished up more people. It was difficult work to get along as the load was so great, and water began to pour into the boat, and some of us were practically up to the waist in it, but still the boat kept afloat.

Whenever we had the opportunity, we hauled women and children into the boat and on to the raft. Some of them appeared to be dead, but fortunately the sun was powerful, the sea was calm, in fact it was a lovely day and after restorative methods had been adapted, these poor creatures revived.

The boat and raft floated about for two hours, and ten we sighted a fishing boat some miles away. Not long afterward, we saw smoke from the funnel of one steamer and then another.

Two destroyers were the first to arrive, followed by three steam trawlers.

The rescued passengers were transferred from the lifeboats to these vessels. I and the survivors in our boat were taken on board the Bluebell about 7:30 p.m., and the she proceeded towards shore other passengers were picked up out of the water.

Some of the scenes were awful and almost beyond description. As we passed along, we saw hundreds of dead bodies. Many of them had lifebelts on, but their heads were under the water. These must have succumbed to exhaustion.

Maitland Kempson died in Birmingham on February 15, 1938, at the age of 77.

Charles Bowring, of the prominent shipbuilding family, witnessed the debacle of the port side boats, and swam clear of the sinking Lusitania from her starboard side. He wrote a long account, in letter form, for his wife:

We had a splendid passage, calm as possible, sighting land about eleven o’clock Friday morning. Fog before that, but bright and sunny from 10 on.

I was at lunch when there was a concentrated thud. My first thought was “They have got us!” and I went out of the saloon to the companionway. The explosion was close to where I was sitting on the starboard side, D deck, at Purser McGovern’s table. Only two at the table, Miss Paynter and myself, out of six were saved.

The explosion broke the ports and I saw the column of water, so the devil must have hit us just by the elevators almost exactly amidships. There was, of course, a crowd rushing up the companionway, excited, but no panic and no yelling. Dr. McDermott, who you remember on the Carmania, was in the companionway telling everybody to keep calm and all would be well.

I got to B Deck and went to my cabin and got two life belts, and then went up to A Deck, port side. There was an enormous crowd, it seemed to me mostly steerage passengers, awful excitement but no panic, sailors in the boats which had been swung overboard the day before and helping women and children in. I gave the two life belts to two women and then saw Mr. and Miss Paynter who Fred Bush telephoned to you about. She had on a life belt, but wrong, and I fastened it properly.

I then made up my mind to get as many life belts as possible and I went down to B deck again and got two out of a stateroom and picked up a third in the passageway. I got up to A deck and tried to get out on the port side, but she had listed badly and the jerk threw me out of the starboard door on this side, which was then getting very close to the water. There were very few people, and I only saw one woman, to whom I gave a life belt, and a man grabbed the other and I put on the third. I saw that she was doomed and soon kicked off my shoes and jumped in, not more than five or ten feet.

I made for a lifeboat, but saw she was not clear and the davits were falling in to her and so I swam away from the boat. I looked back and thought I was caught by the second funnel, but cleared that and then thought the third had got me, but just cleared that by what seemed like a few inches.

She sank by the bow but was turning on her starboard side and went down that way. I do not think I exactly saw the last of her as I was trying to swim clear.

I swam to a flat bottom boat and scrambled, helped by a steward, on top. The canvas cover was still on, and we ripped this up and tried to put on the canvas sides. We found, however, on opening her that her bow was stove in, and we were only kept afloat by her tanks or water tight sides. Oars were got out, but she was waterlogged and we could do nothing.

By this time, we had hauled on board four women and about ten men. She looked as if she would go under us, but providentially an upturned flat bottom boat floated by, and we fastened her to our boat and moved the women, and part of the men including myself, over. She was flush with the water and we stood in her three hours and a half, water washing over our ankles. We were practically helpless, but managed to get two more women off some wreckage and three men, who were drifting by, on our two pieces of wreckage. There was nothing in sight. We simply waited for something to turn up.

After three hours, we saw a motor boat pick up some people a mile from us and then saw a number of smokes coming from Queenstown way. My watch stopped at 2:39 and a man on the Bluebell told me it was 6 o’clock when they picked us up.

It was perfectly calm, luckily, for had there been any sea we could not have held on, and only those few who got away in the lifeboats would have been saved.

It took us four hours to get to Queenstown, and we had to wait another hour while another trawler was landing survivors and bodies. We did not get ashore til nearly 12.

Saturday was awful. The bodies were in three different places and coming in all the time. I tried to identify all I knew for the sake of their families. It was a terrible job, but one could not think of self under the circumstances.

Mr. Bowring had been a ship owner and a ship agent for about 25 years in 1915. The family companies were Bowring & Co., of New York; C.T. Bowring Company of Liverpool, and Bowring Brothers in St. Johns, Newfoundland. The Bowring family had a fleet of 46 ships at the outset of the war. Charles was called to testify at the Limitation of Liabilities hearing in NYC, in 1918, and the most interesting portion of his court appearance was his detailed account of the troubles encountered in lowering the lifeboats:

I should say that the way the boat was going, it was almost impossible to get the boats safely into the water, loaded as they necessarily were with a full complement of passengers.

I saw the first boat that I got quite close to the companionway– they were just filling it and as they started to lower it the passengers were very excited, naturally. They were not panicky, but they were very excited and they were around the ropes interfering with the working of the ropes and getting in the way; and the first boat was going down, and the officer said “Let her go a little faster by the stern” and the man that had charge of the falls evidently could not let it go quick enough, so he threw a bight of the ropes off the cleat and the stern absolutely lost control then. And the boat went right down stern first, held up by her bow. I looked over the side and saw the passengers being spilled into the water. That was the first boat.

She dragged from the falls; there was nobody to clear her; she was held up by the forward fall; she was dragging along in the water.

It was the boat I was– I think it was a little aft of the main companionway on the port side.

The three I saw attempted to be launched were 12, 14 and 16; that is to the best of my recollection.

The next boat that they started to lower, and she went down on an even keel and got, I should say, halfway down when I was looking over the side and saw that they evidently lost control of her, the falls, and she went down straight on an even keel, right down on top of the people that were in the water out of the first boat.

She dropped, I should imagine–the last twenty feet she went down absolutely straight, about as fast as she could go, and dropped right into the water.

It must have hurt the people that were in the first boat; the time was very short between the time they lowered that boat and the second.

Oh, it was a question of fractions of a minute; I should imagine that they were putting people into the two boats at the same time, and they practically started at almost the same time. The boat had gone so far ahead that the people had dropped out of the first boat when the others were coming down; I should imagine it was a question of seconds.

The third boat I saw, they tried to lower her, but the list had become greater, and the stay between the davits broke and the davits and the boat had swung inboard. It was at that time I made up my mind that owing to the momentum of the Lusitania the chances of lowering boats were very slight, and I thought the best thing was to go and see how many life preservers I could get.

He said, of the starboard side:

One boat -I think it was probably 7, that was there; they were trying to lower her, and there was a steward just aft of 7 or 9, who quite calmly remarked to me “Mr. Bowring, wouldn’t you like to be on the Stefano right now? I was with you in her on one of the trips last year”; but she went down, and they were having great difficulty in getting her in, and after I jumped I looked back and didn’t think she’d get away from the ship. The davits were then practically right in the boat.

Charles Warren Bowring, 69, died in New York City on November 1, 1940.

Third class passengers Harold Taylor, 24, and his wife Lucy, 19, of Niagara Falls, New York, were on their honeymoon, and en route to a visit with Harold’s family in Manchester, when they survived the Lusitania disaster. Harold’s account remains one of the best given by a passenger who escaped from the starboard side:

Harold and Lucy Taylor

(Courtesy Wes Taylor / Mike Poirier collection)

We were informed on Friday that the light would be put out so that we could make a dash in the dark for Liverpool. So in the middle of the day I and my wife went into the cabin to pack our things. We were doing this when there was a sudden shock which threw me against the side of the cabin. We rushed into the dining saloon where lunch was on, but as I had forgotten the lifebelts I had to go back to the cabin for them. When I returned to the saloon the ship was listing heavily. There were few signs of panic, though people were of course rushing out of the saloon to get on the decks.

I and my wife got on the second deck, and as my wife ran I managed to fasten a lifebelt on her. We had no instructions on what to do in case of an accident, so we followed the crowd and made for the low side.

Only women and children were allowed to get into the boats. The first two capsized as they were being launched. I managed to get my wife into the third, which was number 15. The boats hold 50 people, but my wife tells me that there were 86 people in her boat. There was no plug in the boat, and she took I water so that it was necessary to bail. Shortly afterwards, some of her passengers were transferred to another Lusitania boat.

When my wife left, I noticed that all of the boats that had been launched were full of passengers except for the last two, and they rapidly filled. The crew seemed to be struggling with these. I saw there were too many, and I just held back on the deck and waited. The last boat to be launched caught the davits and all its occupants were thrown into the sea. I was on deck when the vessel went down, which was not more than eighteen minutes after she was struck.

After she sank, a minister’s wife, myself, and another man were sucked in to one of the funnels and we were all shot out again immediately after as black as soot. Members of the crew afterwards explained that the expulsive force had been a rush of steam from the boilers. I then got caught in the suction and dragged down. I seemed to be revolving all the time. I kept going down and down- for how long I cannot say, for I was practically unconscious.

When I came to the surface I managed to grab hold of a broken oar which was floating past. This enabled me to get my breath again, and certainly saved me from drowning.

Then I drifted against a waterlogged boat with the bows broken in. I clutched at it, and by great effort got inside. Two ladies and a man were holding on to the other end. I dragged in the two ladies and the man got in himself. Then two stewards floated alongside and got in.

There was water in the boat up to within six inches of the top. We had to start bailing at once. We used a small bucket we found in the boat, an old hat, and the glass of a lamp, and later we secured another bucket that was floating in the water. We were bailing for 2 and a half hours, the water running in as fast as we threw it out. The ladies, standing knee deep in water, did a splendid share of the work and set us a very good example.

We picked up yet another man. The water seemed to be full of dead bodies and wreckage. Doors, chests of drawers and all sorts of things were floating about. Our boat was stationary. We could not work her; only keep bailing out the water. It was two hours before any relief vessel came in sight. We were eventually picked up by a destroyer and taken to Queenstown.

Mr. Taylor’s parents were expecting him and Lucy to arrive aboard the Megantic. Saturday morning, the day after the disaster, the family received a letter from Harold advising them that they would be arriving aboard the Lusitania instead. The Taylors were thrown into a very “agitated” state that was alleviated later that morning when a telegram announcing that Harold and Lucy had survived was delivered.