Mauretania History Comes Alive in Bristol

There is more for ocean liner enthusiasts in the English city of Bristol than simply visiting the S. S. Great Britain.

The world’s first great ocean liner, the Great Britain was built by the influential engineer Isambard Kingdom Brunel at Bristol’s Great Western Dock in 1843. It was, and still remains, a masterpiece of ship design and engineering, being the forerunner of all modern ships. Restored to its former glory over the years, the Great Britain has become a popular tourist attraction along the Bristol waterfront.

But for those interested in 20th century ocean liner history, there is the Met Bar Club Diner in Park St., just a stone’s throw away from Bristol Cathedral. This watering hole features many of the fittings and fixtures from the Cunard Line’s legendary first Mauretania. Incorporated in the bar’s design are the ship’s stateroom panelling, plasterwork, mirrors and light fixtures, as well as a large glazed dome from the liner’s library. The artefacts were bought at auction by Ronald Avery, a Bristol wine merchant, and installed in the Avery Building in 1935, shortly before the ship made its final voyage to the Scottish breaker’s yard at Rosyth. Since then, these artefacts have become a popular attraction for ocean liner enthusiasts visiting Bristol.

The R.M.S. Mauretania

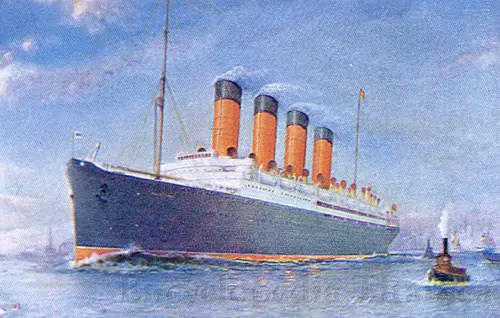

The R.M.S. Mauretania is unique in being the only four-funnelled ship of British registry destined for north Atlantic service to be built in England. The ship’s consorts, the ill-fated Lusitania and Aquitania, were constructed at John Brown & Company’s yard on Clydebank in Scotland, while the White Star Line’s Olympic, Titanic and Britannic were all built by Harland and Wolff in Belfast, in what is now Northern Ireland.

Vintage postcard showing the Cunard Line’s main express liners between the wars. Left to right, the Mauretania, Berengaria and Aquitania.

The Maury, as it was affectionately known, was launched at Newcastle upon Tyne from the Swan, Hunter & Wigham Richardson Limited shipyard in 1906. Its construction, and that of its sister ship the Lusitania, was partly financed by the British government to ensure the Cunard Line remained under UK control. The White Star Line, its chief competitor, had already been swallowed by financier J. Pierpont Morgan’s American-based International Mercantile Marine shipping cartel in 1902.

The Mauretania registered 31,938 gross tons, was 790 feet long and 88 feet wide, and contained steam turbines and quadruple screws. The ship had a service speed of 25 knots and capacity for 2,335 passengers-560 in first class, 475 in second class and 1,300 in third class. It was powered by 25 boilers and 192 furnaces with a storage capacity for 6,000 tons of coal.

Many observers claim the Mauretania to be the most successful and graceful Edwardian-era passenger liner ever built. The ship was virtually a floating palace, and no expense was spared in its construction and internal design. The interiors represented the best that money could buy at a time when Britain was striving to regain supremacy in the north Atlantic commercial trade from Germany. Decoration ranged in style from French Renaissance to English Country, and the woods that were used came from English and French forests. The liner’s first class main lounge, decorated in 18th century French style, was considered one of the vessel’s most impressive rooms. The Mauretania also featured lavish lounges and a verandah café, smoking rooms, libraries, private parlours and an exotic palm court. The ship even had a two-tiered first class dining saloon and the first hydraulically operated barber’s chair.

The Mauretania and its sister were also built for speed. The Maury captured the Blue Riband from the Lusitania for the fastest north Atlantic crossing early in its career, reaching speeds of over 26 knots. Even more remarkable, it maintained the Blue Riband record until 1929, when the German superliner Bremen entered service and completed the crossing with an average speed of over 27 knots.

The Mauretania served in the First World War as a hospital ship and troop carrier, safely transporting thousands of British, Canadian and American soldiers through hostile waters and to and from war zones. During this period, the ship’s panelling and marble fixtures were carefully protected with coverings of wood and cloth. The liner resumed normal commercial sailings in 1920 and shortly afterwards was converted to oil-burning boilers.

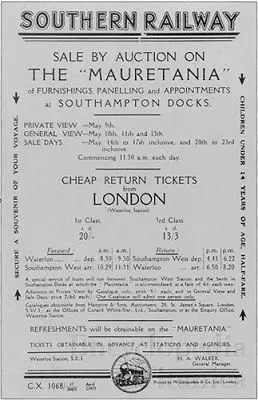

The Maury played out its final years in part-time cruise service. Painted white in 1930 for heat resistance, it sailed to unfamiliar ports such as Bermuda, Havana and Nassau. Desperate for Depression-era business, Cunard offered 10-day cruises on the Mauretania with an all-inclusive price starting at $140 (US). The end came with the merger of White Star and Cunard in 1934 and the planned construction of new, modern liners for the combined fleet. The Maury’s last transatlantic crossing from New York commenced on 26 September, 1934. By the end, it had logged more than 2,000,000 miles and completed 318 Atlantic sailings and 54 cruises, as well as undertaking vital wartime service. The ship was laid up in Southampton and eventually sold for demolition to Metal Industries Ltd. of Glasgow. Before the final voyage to the breaker’s yard, an auction of the Mauretania‘s appointments was conducted at the Southampton docks by Hampton & Sons in May 1935. This is when Mr Avery bought the fittings for the Met in Bristol.

“The Met”

The Met, which is promoted as a sophisticated bar for the over 25 year-old crowd, has extensive wood pannelling from the Mauretania throughout its ground floor location. Additional panelling and fittings can be found upstairs and downstairs, but the great majority of it is in the Met lounges. This wood was originally carved to perfection by 300 craftsmen brought from Palestine to the shipyard on Tyneside. The Met has several large rooms featuring the ship’s panelling. Above one of the doorways leading to what was once the ship’s first class lounge, and later the Blue Riband Restaurant when the Met was known as the Mauretania, can be found the Cunard Line’s emblem in inlaid wood. Patrons can kick up their heels under the large domed skylight from the ship’s library, which sits over the Met’s main dance floor.

The Met has three bars and is one of the city’s hottest nightspots. If you go early in the evening before the crowds arrive, you can get an unobstructed view of the ship’s appointments. When I was there in October 2001, the staff were more than willing to allow me to look around freely and take pictures of the establishment. A pleasant surprise was the two-for-one happy hour on offer, with pints of cider costing only £1.30!

The Met is located at 7-11 Park St. in Bristol. It can be reached by telephone on (0117) 9272766 or by fax on (0117) 9873235. If you are coming from the city centre, it cannot be missed. Look for the building on the left-hand side as you go up the street with the word “Mauretania” in bright lights and a moving image of the famous ship slicing through north Atlantic waters.

References

Frank O. Braynard and William H. Miller Jr., Picture History of the Cunard Line 1840-1990, (Dover Publications: New York, 1991).

William H. Miller, Jr., The First Great Ocean Liners in Photographs: 193 Views, 1897-1927, (Dover Publications: New York, 1984).

John H. Shaum Jr. and William H. Flayhart III, Majesty at Sea, (Patrick Stephens: Cambridge, 1981).

Promotional materials from the Met Bar Club Diner, Bristol, (undated).

I have a ships wheel which My dad bought from an auction back in the ’30s which he was sold as from the mauretania, but I have no evidence is there any way I can verify this ?

Any help would be appreciated.

Thank you