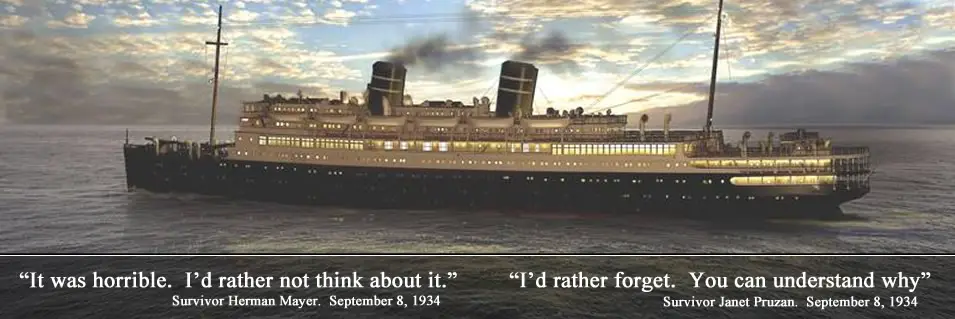

Morro Castle : The Forgotten Voices

One night out from Havana. Aboard the Morro Castle, passengers gather in the Deck Ballroom for a costume party.

In less than four days time, the liner will be destroyed and 128 will be dead.

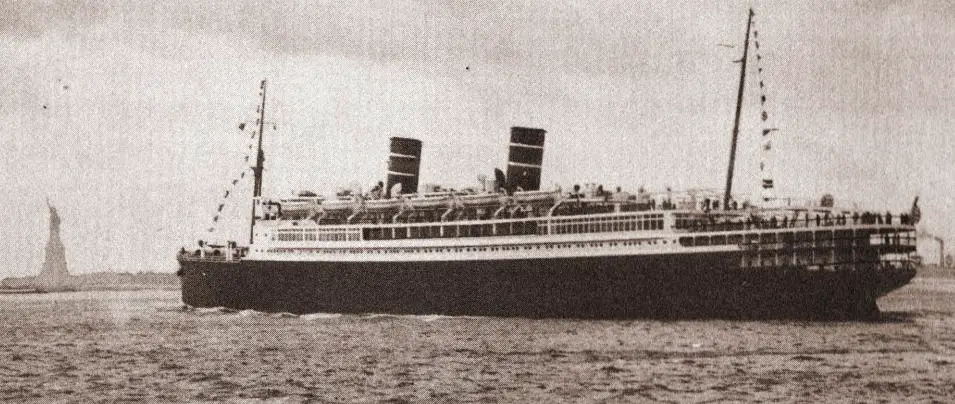

In four hours it would all be over. The Morro Castle, flagship of the Ward Line, would be approaching Manhattan and her pier at the foot of Wall Street. Her passengers would be returning to the world of every day concerns, carrying with them mostly pleasant memories of seven days spent aboard America’s favorite cruise liner. Outside, the rain that had begun falling early in the evening was beating down, the lights of the New Jersey shore were occasionally visible to port through the storm wrack, and the seas were running high in the face of mounting winds. Inside, most of the passengers had retired for the night in preparation for the controlled chaos of disembarking the following morning, but perhaps two dozen of the more energetic remained awake in cabins widely scattered around the ship, and in the public rooms on B Deck as the clock approached 3 a.m. on September 8, 1934.

Max Berliner, a genial tobacco merchant from Queens, New York bade farewell to the last of the guests who attended his stateroom party. Mr. Berliner was traveling in Deluxe Cabin 10 on A Deck, located directly above the liner’s writing room. His party had been well attended, with many passengers dropping in over the course of the evening, but now with disembarkation only a few hours off, his final guests, Mr. Israel Rudberg, Mr. Milton Klein, Miss Adele Wallace, Miss Sydney Falkmann and Miss Elmira Thompson took their leave. Mr. Berliner would be returning to his wife and three children in just a few hours and it is likely that the 41 year old man soon went to bed to rest up a little for what would surely be a busy day.

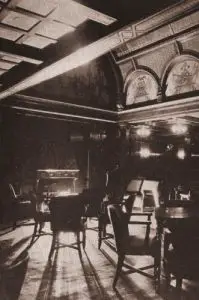

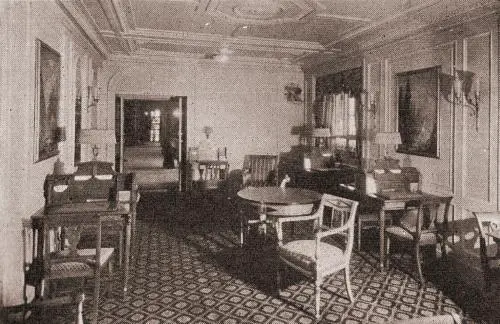

Writing Room

Miss Eleanor Brennan, head buyer for the Curtains and Draperies Department of Macy’s Herald Square store, also hosted a stateroom party that evening. Eleanor had come far on her own. Born in a rural community, she had been compelled to drop out of school to raise her younger siblings upon the death of her mother. When the children were old enough to be self sufficient, she began commuting to New York City, took a job at Macy’s and worked her way up through the ranks. She was unmarried at 38 but, by all accounts, was not suffering for it. She traveled in one room of the ship’s finest two room suite, C-235/37, and was taking her second Morro Castle cruise of 1934. She and her friends, among them cousins Helen Brodie and Agnes Berry, Father Raymond Egan and his cabin mate 16 year old Louis Perrine, and Mary Robinson and her teenaged daughter, Lucille, decided not to go to bed at all, and a little before 3 a.m. put in a call to room service for sandwiches and Highballs to be sent up to C-237. So, when a knock came at the cabin door around 3:30, there was no reason for the guests to suspect that anything was amiss.

German Vice-Consul to Cuba, at Matanzas, Clemens Landmann and his wife and daughter occupied the next cabin aft of Eleanor Brennan‘s. Mr. Landmann had served as a diplomat in Cuba since 1912. His daughter Marta, born in 1922, spoke only Spanish and Mrs. Landmann, shown as “Jose” on their FBI statement, was apparently a Cuban. The Landmanns retired early, but the noise carrying over from Eleanor Brennan’s cabin kept the Vice-Consul awake and some time after midnight he took a sleeping pill.

Miss Marjorie Budlong, of Hillside, New Jersey, an 18 year old student at Greenbriar Junior College, sat in cabin A-17 with her friends, Rosario Camacho and Doris Wacker. Marjorie was traveling as the guest of the Wacker family, and she and Doris had become acquainted with Miss Camacho, an 18 year old Cuban who was en route to her apartment near Columbia University in New York City. The three decided to stay up and see in the dawn as the ship entered New York Harbor, and had passed the evening having the aimless sort of fun one has on the last night at sea. They visited with friends in the lounge, passed time in Miss Camacho’s cabin admiring her expensive wardrobe, and as the public rooms were beginning to empty out, went for a time to Miss Budlong and Miss Wacker’s stateroom C- 214 so that they could finish packing and Doris could change from her formalwear to street clothing. When they returned to Rosario’s cabin, it was a little after 2 a.m. and they saw nothing amiss in the empty writing room and nearly empty lounge through which they passed. The girls talked for nearly an hour, and at some point set their watches ahead to Daylight Savings Time. Doris Wacker grew tired and decided to return to her room. Miss Camacho rose to open the cabin door to see Doris out, coincidentally noting by her watch that it was 3:10 a.m.. From where she sat in the cabin, Miss Budlong thought that she heard Doris scream ‘fire!’ as she stepped in to the hallway, but from where Miss Camacho stood at the open door it was apparent that the scream had come from one deck below, in the lounge.

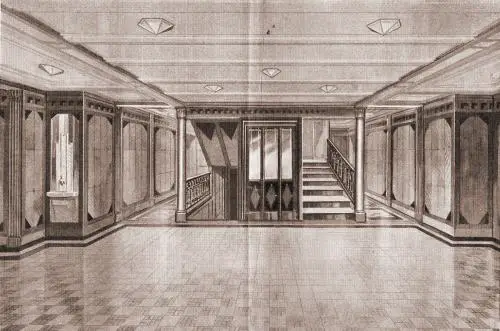

Lounge – viewed from the writing room door towards the balcony from which Miss Budlong watched the fire

Miss Camacho‘s stateroom was one of the deluxe cabins that lined A Deck, also known as the Boat Deck. It was located just aft of the balcony surrounding the well on the upper level of the ship’s lounge, and taking a few steps forward from her door would give a person an unobstructed view of the grand, wood paneled, room below.

The three friends rushed to the rear starboard corner of the lounge well. From where they stood, they could look diagonally, downward, into the writing room through the open doors on the forward port corner of the B Deck lounge. The carpet in the writing room was in flames, which covered the floor and rose perhaps two feet high. A man and a woman stood by the door of the room and from where the girls stood it looked as if the man wanted to attempt to fight the fire and was being restrained by the woman. A steward was calling to someone to hurry, but the girls could not see at whom the order was directed. Marjorie Budlong saw two men throwing something from buckets on to the flames, and a crew member called up to her that the fire was under control and not to worry. All three girls noted that no smoke was entering the lounge.

They went back to cabin A-17, where Miss Camacho locked her window, closed and locked her trunk, and grabbed her handbag into which she had placed several thousand dollars worth of jewelry. When they returned to the lounge well railing, they were surprised at how quickly the fire had spread in the short time they were away. Flames were roaring aft, consuming the lounge carpet, and spreading across the room towards its port and starboard walls. The three turned and retreated from the inferno moving towards them.

The Morro Castle’s B Deck public rooms were elaborate, wood paneled spaces, with a decidedly pre-World War One atmosphere. The focal point of the suite was the lounge, which rose through two decks and filled the entire space between the ship’s two funnels. Because of the funnels, the lounge did not have a grand entrance- passengers going to and from the room had to pass through either the port side writing room or starboard side library to reach the Grand Lobby with its elevator and staircase. The equivalent spaces aft of the lounge were not occupied by rooms, but by hallways leading to the smoking room. The whole area was so well traveled, at all hours, that a fire could not possibly gain much headway without being discovered.

Ann Conroy

James Flynn, of Philadelphia, stood in the B Deck lobby just forward of the writing room. He had made the acquaintance of pretty Ann Conroy, also of Philadelphia, and the two passed a quiet hour together walking the length of the enclosed promenade decks that flanked the public rooms and deluxe cabins of B Deck. There was a chill in the air, and Mr. Flynn had excused himself to return to the cabin he shared with Milton Klein (D-355) in order to get a pair of steamer blankets. Passing through the deserted writing room, he heard a strange crackling from behind the door of a locker in its rear port corner. He headed back into the lounge, where a steward stood talking with some passengers. He brought the steward into the writing room, and when the man opened the locker door flames leaped out into the room. The steward slammed the door shut, but it swung open again and the flames set the carpet on fire. The steward ran aft into the lounge and Flynn ran forward through the lobby and passenger corridor of B Deck looking for a fire extinguisher. He did not find one. When he returned to the lobby, a passenger was pulling the fire alarm, and no smoke or flames had entered the area forward of the writing room. Crew members, wearing rubber gear, entered from the port side with a hose, and Mr. Flynn exited through the door through which they had just run and returned, aft, to where Miss Conroy was waiting.

In his cabin directly over the writing room, Max Berliner never stood a chance. Evidence indicates that he woke up at the last second. His remains; teeth, a few charred bones and a Masonic ring, were found in the middle of the floor of Deluxe Cabin A-10, and not mingled with the remains of his mattress. In a stupor from the intense heat and smoke, he may have tried to reach the door or window of his room before collapsing. Only 45 minutes before, more than a dozen people had been taking light refreshments in the first spot aboard the ship to become unsurvivable.

Fannie Fryman and Ann Litwak

Loretta Hassall, a 20 year old college student from Forest Hills, New York, had parted from her friends of the voyage, Henry Borman, Ann Litwak and Fannie Fryman moments before the writing room locker caught fire. The four had passed the evening conversing in the lounge, but at ten minutes of three they took the hint when a crew member began vacuuming the room around them and decided to retire for the night. Loretta noted that two women remained in the room, attempting to sleep on the sofas by the fireplace. She briefly dropped in to the smoking room, where a few passengers remained awake, and then walked forward to the main lobby, passing through the empty library on the starboard side of B Deck. She noted no smoke or flames in the lounge, but when she stepped from the library into the lobby, she saw fire pouring out of the writing room door, towards the staircase. A man was pulling the fire alarm. She turned and ran back towards the smoking room, calling out “fire!” as she went.

Loretta’s mother and father, Elsie and James Hassall were asleep two decks below the writing room, in D-304. 304 was an inside cabin, one of only a handful aboard the ship, and was located just forward of the grand staircase. Elsie was awakened by the smell of smoke entering through the ventilation system, and noted by her husband’s watch that it was 3:15 a.m. She opened the door to her cabin and saw nothing amiss. She must have walked a few steps back to the lobby, because she would tell the FBI that she went to where she could see a porthole through which the reflection of the fire on the ocean was visible. She ran back to her cabin and woke up Mr. Hassall. They put on their life preservers and then pounded on the door to D-310, in which their 16 year old daughter Ethel was asleep. Assistant cruise director Herman Cluthe came up and told them to be quiet, and that everything would be all right. The C Deck lobby was empty, but when the Hassalls and a group of passengers walked up to B Deck they came across a scene of great confusion. People ran in all directions, and although they saw no flames, a great deal of smoke was pouring out of the writing room door and filling the port side of the room. The Hassalls exited through the starboard doors to the promenade deck and went astern, to the aft grand staircase. They wanted to go up to A Deck but were prevented from doing so by people coming down.

Morro Castle’s foyer and staircase

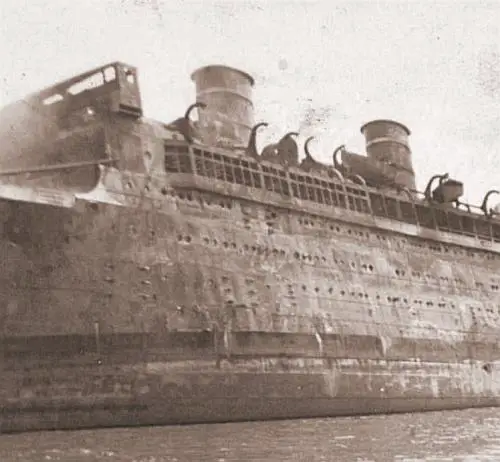

The location of the fire, amidships on an upper deck, was singularly unfortunate. While the Morro Castle continued to sail northward, the flames were driven back through the lounge and smoking room, cutting off access to the boat deck by way of the aft grand staircase. Just forward of the B Deck lobby was a series of eight luxury suites. These rooms were the only large block of cabins on ship to remain unoccupied. Perhaps twenty minutes into the fire a massive explosion, originating forward on B Deck, rocked the ship. It blew the flames into the forward staircase, cutting off upward escape for the occupants of cabins on C and D Decks. And no choice remained for most of the passengers except to head to the small, open, promenade decks that ringed the stern of the ship. Water, from outlets that had not been turned off when the crewmen and passengers manning hoses dropped them in the face of overwhelming defeat, sloshed on the floors. Thick, noxious smoke blew back overhead along the passages and, as it settled downward, it burned eyes and throats. Although the ship had an alarm system, and at least two passengers saw it being activated, the majority of those on board never heard it. Some were awakened by dutiful crew members. Others were roused by friends. Most, it seems, woke up reflexively when they smelled smoke, or were startled awake by the sound of running, and screams, in the hallways outside of their rooms. Many instinctively headed for the stairs, only to be driven away by the flames, and soon found themselves part of the same mob that had awakened them minutes before, heading for the stern. When the electric system burned though, perhaps a half hour into the disaster’s progress, people had only the reflected light of the fire to guide them along.

Mr. and Mrs. Henry Jakoby, of Ridgewood Avenue, Brooklyn, and their 17 year old son, Henry Jr., were asleep in cabin D-361. The Jakobys were traveling with the Concordia Singing Society, of which they were not members, at the invitation of their friends Martin and Marie Renz, and Jacob and Minnie Likewise. Henry Jakoby was a brew master at Piels, while Mr. Likewise and Mr. Renz both worked in the painting trade. The Jakoby family had gone to bed at about 1 a.m. after packing their clothing and souvenirs. They were awakened by their friends pounding at the cabin door at a quarter to four. They only had time to partially dress, and put on their life preservers. Henry Jr. led them forward, but the way was impassable and to the group’s horror, the flames that were rolling down the staircase set his sleeve ablaze. They turned and fled aft.

Miss Anne Behling awoke in cabin C-246, to the smell of smoke and the sight of fire reflecting off of the water outside of her cabin. Miss Behling was the private secretary to the Vice-President of the Atlantic Refining Company in Philadelphia, and her secure position afforded her the opportunity to travel frequently, by 1934 standards. She was a repeat voyager on the Morro Castle, and as such had been given a tour of the bridge by Captain Wilmott on the southbound leg of the cruise. He explained the workings of the ship in some detail, and told Anne of the fire prevention system, and of how the vessel could be divided into separate “containment” sections in case of the outbreak of fire. Miss Behling put on her coat and slippers and went out into the starboard corridor. She recalled, later, that there was much confusion. People did not know in which direction to head, and were asking one another, and crew members “What is happening?” Anne decided to walk forward to the grand staircase, but when she got to the dining room mezzanine she saw a wall of fire not more than ten feet ahead of her, blocking forward access along the port side. A man called to her “You can’t use this stairway- you’d better use the back.” She headed to the aft grand staircase and managed to climb it all the way to A deck.

Ann Conway, of Prospect Place, Brooklyn, was startled by the sound of someone running in the corridor outside of cabin 230. She heard a child say “Mother, I haven’t got any life preserver.” Miss Conway was part of a group of congenial young people who socialized during the voyage, and had spent the final night aboard the ship dancing and playing cards with her friends Florence Roberts, Louise Taubert and Floride LaRoche, all of Rhode Island; Thomas Peirce, Morton Lyon, and J.M. Chalfonte, a trio of friends from Pennsylvania traveling together; Gouverneur Morris Phelps, Jr, of New York City, and Mr. Francis Stewart of Riverdale, New York. The party had broken up about an hour before Miss Conway’s sudden awakening. She ran across the ship and pounded at the door of cabin 219, where her three female pals were asleep, calling out to them that there was a fire.

Mrs. Frieda McArthur awoke in cabin C-256, feeling indisposed. She rose to take some medicine and, as she returned to bed, heard the sound of running in the corridor outside of her room. She saw fire reflected on the water beyond her porthole, and saw showers of sparks falling past. Alexander and Frieda McArthur took yearly cruises with their friends Herman and Lillian Wacker, and were joined on their 1934 expedition by Steven and Wilhelmina Bodner, the Wacker’s daughter, Doris, and Doris’ friend Marjorie Budlong. As Alexander McArthur dressed, Frieda ran to awaken the Bodners, who were emerging from the door to cabin 242 wearing their life jackets as she arrived. She then ran back to join her husband. They grabbed their life jackets and went aft along C Deck.

Charles and Selma Filtzer, of Kew Gardens, Queens, NY. were on their honeymoon. They retired to cabin D-318 at 12:00. Charles was the resident buyer for May & Co., on Broadway in New York City, and an avid sportsman. Selma was his first sweetheart, and they had been married only a week on September 8th. Mrs. Filtzer was shaken awake by her husband some time after 3 a.m. Their cabin was filled with smoke, which had presumably awakened Charles. The Filtzers did not hear any alarms, no one knocked at their door, and unlike many other passengers they were not startled awake by the sounds of panic in the corridor outside of their cabin. They put on coats and went to investigate. Selma noticed that water, from the abandoned hoses, was quite deep in the corridor outside of their stateroom. They returned to their cabin, got life preservers, and put them on. They made their way aft and upstairs to B Deck, and while they were climbing, the electricity failed.

Abraham Cohen

Abraham and Harriet Cohen, of cabin C- 215, were also honeymooning aboard the Morro Castle. Abraham, a star high school athlete and Dartmouth graduate managed his family owned Grand Department Store in Hartford, Connecticut, while Harriet had attended Smith College, graduated from Simmons, and worked in the comptroller’s office at the G. Fox department store until her marriage. Earlier in the evening, the Cohens were among the guests at Max Berliner’s party. Harriet was startled awake by the sound of running and shouting in the hall outside of her cabin. Abraham remained asleep as she left the room and walked up the Grand Staircase, located steps from their door, to B Deck. There she saw the fire and mounting panic. Someone in the lobby gave her a child’s life preserver and helped her to put it on. She returned to her cabin and woke Abraham. He put his life preserver on. When the Cohens left the cabin, the fire had entered the staircase and was moving down towards the C Deck lobby. Abraham noticed passengers with a hose aiming water towards the ceiling. The Cohens walked aft to warn their shipboard friends, Mr. and Mrs. Samuel Vitale, and when they arrived at the Vitale’s cabin the couple was just emerging, in street clothes, and wearing their life jackets. All four went aft to the open promenade deck at the stern.

Israel Rudberg, of Shenandoah, Pennsylvania, awoke to the sound of strange noises in the corridor outside of his cabin, C-274. He had left Max Berliner’s party with Milton Klein and Adele Wallace a little more than an hour before. When he opened his door he saw passengers with life jackets heading aft and smoke blowing back towards them. By his watch, it was about 3:10 a.m. He went aft, and up to A Deck while the stairs were still passable. He joined a crowd of passengers he estimated to number at least 40 who gathered at the rear of the liner’s boat deck.

David Schneider, in cabin A-12, awoke to discover flames coming through the cracks under and around his door. Mr. Schneider had left Max Berliner’s party early, after spending time there with the Cohens and Miss Falkmann, and went to the nearly empty lounge to enjoy a cigar. He sat in a chair on the starboard side of the room, from which he could look into the library and across at the door to the writing room. When he left at 1:30, he noted that a boy in a dinner jacket and a girl in a white gown were still in the lounge. He was awakened by the smell of smoke around 3:10, began to drift off to sleep again, and was jolted fully awake as the fire entered his room under the door. He climbed out of his window on to the boat deck as the cabin burst in to flames.

Joseph Bregstein

Mervyn Bregstein

For Dr. S. Joseph Bregstein, the Morro Castle voyage had been a bittersweet occasion. His wife, Ethel, had died in January 1933, at the age of 29. He subsequently met, and fell in love with, Miss Muriel Rubine and by September 1934 was planning to marry her. The cruise to Havana was meant to give the Doctor and his nine year old son, Mervyn, a chance to discuss his re-marriage, but the talk never took place and neither father nor son had particularly enjoyed the Morro Castle. They occupied Cabin D-301, a deluxe cabin at the furthest point forward on the starboard side of D Deck. Dr. Bregstein was a sociable man and made the acquaintance of many passengers. Some would later remember him playing popular music on the lounge piano. On the final night, he and Mervyn turned in at 9:30. His last act before retiring was to set his watch ahead one hour – he had read a notice about ship’s time and shore time earlier in the day, and remembered it as he prepared his son for bed. Mervyn had reddish hair and freckles, and was deeply tanned after spending the summer away at camp. He was to start the new school year on Monday morning.

Jane Adams awoke the Bregsteins by pounding on their cabin door. She called to them that the ship was on fire. Joseph Bregstein and Mervyn dressed, with the Doctor buttoning a yellow rain slicker over Mervyn’s clothing before they stepped into the hall. They neither saw nor smelled smoke, but noticed water running over the floor in the hallway. Dr. Bregstein observed a flat hose on the floor and assumed that it was the source of the water. They walked back to the lobby, where people hurried about and water sloshed back and forth on the floor. Father and son climbed up one flight, to C Deck and went aft along the starboard corridor. While they were on the dining room mezzanine, the electricity failed.

Passengers in the Lobby

Dr. Emanuel Weinberger of Philadelphia, awoke in cabin 222, coughing from the smoke he had inhaled. He turned on the lights, and woke his wife. When they looked from their porthole, it seemed as if the entire front end of the ship was aflame. Dr. Weinberger went to make sure his friends, Mr. and Mrs Pannino, were awake. He noted, by the clock in the dining room, that it was 3:20 AM. The Weinbergers walked aft along the port side corridor, and climbed up to B Deck. From the sports deck, they could look forward, and up, to A Deck. The entire deck, including the gymnasium, was already on fire. Men on the port side of B Deck were aiming a hose up at the fire along A and the Weinbergers saw that the pressure was only fair. From the stern of B Deck Dr. Weinberger was able to look down at the water. He could tell by the wake and the suction that the ship was still moving, and was also turning. The Weinbergers saw one lifeboat in the water below them. It was moving away from the ship.

George Whitlock, assistant Vice-president of the People’s Trust branch of National City Bank, was awakened in cabin C-265 by his wife Charlotte, who was concerned because she smelled smoke. 1934 accounts agree that Mrs. Whitlock was hampered by a “crippled” leg, but neither the newspapers nor her husband’s testimony offer a clue as to whether Mrs. Whitlock had been injured in an accident, or suffered from a degenerative condition. George left her in their cabin and walked forward. When he was still ten feet from the lobby, he saw that it was filled with thick, black, smoke. He returned to his room, and told Mrs. Whitlock that there was a small fire. They dressed and put on life preservers. As they were leaving their cabin, the lights went out. But before they went to the stern, and safety, they walked forward to the stateroom of their friends Edward and Adele Brady, to make sure that they were awake and preparing to escape.

Adele and Edward Brady and their 18 year old daughter, Nancy Ann, were awakened in C-263 by the sound of running in the corridor. Edward Brady was in poor health, and the trip to Havana was to be a “restorative.” It is indicative of Mr. Brady’s state that 55 year old George Whitlock would later refer to the couple as “Mrs. Brady and old Mr. Brady.” Edward Brady, at 53, was younger than Mr. Whitlock. Nancy Ann Brady did not like the Morro Castle, and had begged her parents to return from Havana by plane, but they persuaded her to complete the voyage. And now the three found themselves trapped in a waking nightmare. Their friend, George Whitlock, appeared at the cabin to make sure that all three were awake and had lifebelts, before he returned to his wife. The Bradys rushed forward toward the stairs but were driven back by the flames that roared down them. They joined the crowd running towards the stern and found themselves hemmed in against the railing aft of the small lounge on C Deck. Smoke poured over them, choking them and burning their eyes. Edward Brady yelled to his family to jump, and the three of them went over the rail together, hitting the water with what Mrs. Brady described as a terrific impact. Husband and wife rose to the surface and clung to one another, and Mr. Brady repeatedly called for Nancy Ann, but she was gone. The current caught them and they soon drifted away into the darkness astern of the liner.

Nearly all of the Morro Castle passengers and crew were trapped at the rear of B, C and D decks within 45 minutes of the fire’s discovery. Just as the Bradys did, they found themselves confronted with the choice of jumping, burning or suffocating, with, seemingly, no other options. A strong authority figure might have prevented all-out disaster from unfolding, but the officers were isolated on the bow, almost 500 feet away. Left to their own devices, those on the stern remained calm and well behaved for a remarkably long time, given the circumstances. Passengers, such as the Cohens, Ann Conway, Jane Adams, George Whitlock and Frieda McArthur delayed their own escape in order to make sure that friends in other cabin were awake and on their way to safety before fleeing themselves. Steward Samuel Petty was last seen, alive, pounding on the doors of the cheapest cabins aboard the ship and rousing their occupants. Yet, despite many acts of heroism and few outright acts of cowardice, the scene on the stern eventually degenerated, as people began to suffocate and rooms not more than ten feet away from them began to burn. There was no organized escape plan, and no one to advise the trapped on how to safely evacuate a burning liner.

Morro Castle Lifering

Estelle Chesler had trouble falling asleep that night. She had been awake for several hours when she was startled by the sound of running in the corridor outside of the stateroom she shared with two of her friends from Brooklyn, Miss Bessie Weinrub and Mrs. Bessie Perlmann. Estelle opened her cabin door to investigate and upon stepping in to the hall saw a passenger fleeing aft. He called to her that the ship was on fire. She awoke her friends. All three immediately fled without grabbing their life preservers. They climbed up the enclosed, aft most, staircase to B Deck, where they saw crew members running forward. The women asked a crewman for life preservers, and received a shrug of the shoulders and a response of “I don’t understand English.” Finally, an English dining room steward gave the three women a small life ring, and they climbed from B Deck to A Deck. They joined a large crowd of passengers aft on the open sports area, by the gymnasium, on the port side. From where they stood they could see smoke, but no flames. They watched an unsuccessful attempt to prepare a lifeboat for lowering, forward of where they stood. Someone ordered the crowd below to B Deck, and the three women, still without life jackets, climbed down again. There they saw steward Pond and gym instructor Marco Apicella. Pond wore a life vest, and Apicella held one of the large Morro Castle life rings. The women asked him the best way to evacuate a ship with a life ring, and he replied that it was best to throw it over first, and then jump down to it. Miss Chesler, Miss Weinrub and Mrs. Perlmann asked if they could hold on to Apicella’s large life ring when they all went in to the water, and he reluctantly agreed that they could. All four watched the flames driven back towards them. The wooden deck began to burn, close to where they stood, and suddenly the gym instructor pulled away from them and went overboard. The three women forgot his instructions on how to use their life ring and jumped from the ship holding it. The impact knocked Bessie Perlmann out, or may possibly have killed her, and she lay face down across the life ring. A woman passenger in a life jacket swam up to them, and tried to raise Bessie’s head out of the water, but then a wave swept over them and Mrs. Perlmann was gone.

Honey Kennedy

Mrs. Ellen Kennedy, of Hamilton Beach, New York awoke to see the pink glow of flames on the ocean outside of her porthole. Earlier in the evening, she and her husband, James Kennedy, had socialized with shipboard friends Joseph and Claire Drummond. The Drummonds had married on the morning of September 1, 1934 in Philadelphia and after a wedding breakfast at the Hotel Normandy, boarded a train for New York City and went directly to the ship. They sent postcards home from Havana telling their families that the voyage had been “swell.” The Kennedys were married 14 years in September 1934, and had a four year old daughter, Ellen, known within the family as “Honey, who remained in New York with Mrs. Kennedy’s parents. Jim Kennedy, unfortunately, had a touch of indigestion and so retired early to bed. Ellen remained with the Drummonds until 12:40 and then went to her cabin and was soon asleep. After awakening and discovering that the ship was on fire, she roused Mr. Kennedy. They dressed, donned life preservers, and went out into the hallway. The Kennedys must have gotten a late start, because by the time they emerged and walked forward towards the stairs, the hall and purser’s lobby were deserted, save for a lone man playing a hose on the fire. The man would not allow them to walk any further forward, and the stairs upward were impassable, so they turned and went aft. En route to the stern they passed a steward carrying a hose. He seemed surprised to see them.

Ellen, E. Jacqueline and Jim Kennedy

Mrs. Kennedy, with her cane and brace, at the 1939 World’s Fair*

Florence Sherman pounded on the door to cabin D-386 until her friends Francis Nass and Nathan Feinberg woke up. The three had attended Max Berliner’s party earlier in the evening, with Mr. Nass escorting Miss Sherman, and Mr. Feinberg bringing a girl named Margie Mayer. The men dressed and put on life preservers, and then walked to the stern of B Deck with Miss Sherman. From where they stood, it seemed that no boats were being lowered and no orders given. When the three asked for instructions, they were told by a crew member not to worry.

Ann Stemmermann

Doris Landes

September 7, 1934, the Morro Castle’s final day, marked another milestone in what Doris Landes of Richmond Hill, New York, considered to be the most wonderful week of her life. She was aboard the ship with her friend and neighbor, Ann Stemmermann, 15, Ann’s mother, Christine, and another near neighbor, Mrs. Marie Byrne. Mrs. Byrne and the Stemmermanns shared cabin 503, while Doris roomed with Elsie and Ethel Suhr in 508. Ann Stemmermann had been a child advertising model, but retired by the mutual agreement of her parents and agent when she reached an age at which sexual harassment might have become an issue. Doris was a student at Richmond Hills High School, and carried a brand new “adult” wardrobe with her on the voyage. The four women had a wonderful time on the southbound leg of the journey; had taken the Ward Line-sanctioned tours in Havana (Shopping, a trip to the beach, more shopping, a car trip of Havana landmarks, more shopping, and an evening at a night club) and Doris sent a letter home to her mother, by airmail, in which she wrote glowingly of their adventures. The final full day of the voyage was Doris’ sixteenth birthday, and she celebrated her “sweet sixteenth” among friends, all of whom agreed that the trip had been even better than anticipated.

A steward’s pounding woke Doris and the Suhr sisters. This was most likely steward Samuel Petty, who was noticed by several passengers pounding on the doors of the liner’s least deluxe cabins (the 500-600 blocks) and calling to their occupants. The steward yelled to them through the door to get their lifebelts and get out on deck. They did not bother to dress. When Doris stepped into the hall, she found that it was filling with smoke that, to her, seemed to be coming from out of the lighting fixtures. She found Mrs. Byrne, and the Stemmermanns. They all joined hands and walked up the stairs to the aft end of B deck, and then attempted to climb to A deck and the lifeboats. From where they stood, the flames over A Deck, pouring out of the destroyed skylight in the lounge, looked as if they were a mile high. The smoke blew back over them, and they began to choke. It seemed as if Marie Byrne was about to collapse. The two married woman and the two teenagers climbed the rail and jumped together, still holding hands. The impact with the water separated them, and Doris found herself drifting away from the ship, alone, in the dark.

* Photographs of Honey, Ellen and Jim Kennedy courtesy of Deirdre Hosen

Marjorie Budlong

Marjorie Budlong, Doris Wacker and Rosario Camacho ran aft along the A Deck starboard corridor, a section of the ship from which they would be the only survivors. The occupants of the next cabin aft of Rosario‘s, Dr and Mrs. Strauch of Donora, Pennsylvania, would die, as would Mrs. Caridad Saenz and her three children, the occupants of the two staterooms aft of the Strauches. Miss Budlong noticed two men in the corridor, but did not comment on whether the men were heading forward towards the fire or aft away from it. They emerged on to the A Deck sports area, in the driving rain. Doris Wacker remarked that she was going to wake her parents, and was told not to attempt it by a crew member. The three friends went down to B Deck, where Doris parted from them and went forward in to the ship to warn her family. Marjorie saw a waiter she knew as “Ralph” putting on a life jacket. When she asked where she could get one, he replied ‘Don’t ask me. I don’t know!’ Perhaps thirty people were already grouped together on the open sports area aft on B deck. Herman and Lillian Wacker, and Doris, appeared, carrying a lifebelt for Marjorie. Herman Wacker was the borough engineer for Roselle Park, New Jersey. He and Lillian had taken many cruises and were not impressed by the Morro Castle. They stood with their daughter and her friends in the crowd, which jammed tighter together as the smoke and heat increased, and waited for orders that never came.

George and Charlotte Whitlock emerged, late, on to the covered promenade on C Deck. Everybody was tightly jammed in, and some were screaming and hysterical. They saw a pair of stewards, but no officers. Slowed by Mrs. Whitlock’s leg, they were among the last to emerge, and realized that because of the intense fire directly behind them, they could only progress upward. George climbed up to B Deck, alone, and found conditions there worse. He returned to his wife on C Deck. Some of the people in the crowd were yelling ‘Get rid of your clothes!’ Others seemed on the verge of panic. In the days following the fire, several passengers recalled seeing the Whitlocks standing calmly together, while others recalled George Whitlock attempting to maintain order in the mounting chaos on the C Deck promenade.

Florence Brown

Alice Desvernine

Among the passengers standing close to the Whitlocks were 23 year old Alice Desvernine of Jersey City, New Jersey; her aunt, Mrs. Florence Brown of New York City, and her cousin, Madeline Desvernine of Tuckahoe, New York. The Desvernines were related to the Pillsbury family, and Madeline, 18, had spent the summer of 1934 at their expansive ranch outside of Havana where, among other things, she learned how to swim. Alice and Mrs. Brown sailed down to meet Madeline at the end of the summer, and all three were returning home aboard the Morro Castle.

Alice was awakened by either the sound of panic in the hall outside of cabin C-244, or by the smell of smoke. She was not sure, later, by which. No alarm sounded, and from her berth she could see the red glow of the fire reflected against the sky. Terrified, but at the same time remaining calm, she woke up her aunt and then crossed to the port side cabin Madeline shared with an unknown woman to be sure that her cousin was awake and effecting an escape. Madeline would later recall her cabin mate shaking her awake and saying ‘You’d better get up. The ship is on fire,’ so, by the time Alice arrived, she had already grabbed her life preserver. When the Desvernines returned to C-244, and their aunt Florence, they observed that great crowds of panicked men and women were forcing their way back towards the stern. All three women took the time to put on their life preservers before stepping out into the mob. None of them knew how to adjust a life belt properly, and initially put them on too low. A male passenger in the corridor stopped them and fixed the preservers so that they were at the proper height. They attempted to climb the aft grand staircase to B deck but were driven back by flames. They found the C deck promenade in chaos. Passengers rushed about, or crowded together. Some cried, others screamed, and a few seemed frozen with fear. The three women watched crew members fighting the fire with a single hose. By this time the electricity had failed, and Alice would later remark on the flickering red glow the flames cast over everything and everyone trapped on the fantail. They knew that people were beginning to jump, and Alice suddenly found herself wondering what had become of the Saenz children, whom she had informally baby-sat on deck the previous day. George and Charlotte Whitlock drew near. They were voyage friends of Miss Desvernine and Mrs. Brown. George had strips of wet fabric, and wet handkerchiefs, which he was distributing among the trapped passengers and crew. He gave one to each of the women, who held them over their faces to filter out some of the rapidly thickening smoke.

Morro Castle: Fantail

James Flynn and Miss Conroy watched the fire burst out on to the port side B Deck promenade and begin rushing back at them along the ceiling. They crossed to the starboard side of the ship, where the wind seemed less fierce and the fire did not spread as quickly. They stood together and watched a lifeboat being lowered. Neither had a life jacket, neither felt it wise to enter the ship to get one, and no one from the crew came along to help them. When the heat and smoke became unbearable, they went over the railing with one of the large Morro Castle life rings and, miraculously, did not lose it when they hit the water. The two clung to it as the burning liner moved away from them.

Ann Conway, Floride LaRoche and Florence Roberts waited by boat 10 on the port side of A Deck. The boats forward of where they stood were on fire, and smoke and flames were coming out of the windows of the cabins and upper level of the lounge. Fire was also coming up over the side of the ship from the Promenade Deck below them. Their friend, Louise Taubert was missing. She, Miss LaRoche and Miss Roberts had been awakened by Ann Conway’s pounding. Ann warned them that they had no time to dress and so they grabbed only life preservers before leaving C-219. Miss Conway noted that Gouverneur Morris Phelps Jr. and another passenger were fighting the fire at the Grand Staircase with a single hose. The women’s way to the boat deck was blocked by smoke and flames and so they went back along C Deck to the aft Grand Staircase by the barber’s shop. It was also impassable. A crew member, possibly Chief Engineer Eben Abbott, led them to a crew stairway by which they gained access to the Boat Deck. At some point Louise Taubert became separated from her friends, who would later claim in a pair of interviews that she hung back, frightened by the fire that was pouring out on to the boat deck, and was lost as the other women ran aft towards the crew members gathering around boat #10. The three women and perhaps eleven crew members entered the boat. There was great difficulty in lowering it, and at one point it jammed on the falls. Broken glass from the Promenade Deck windows rained down on the occupants, and Miss Conway pulled a tarpaulin over her head to protect herself from it. There was no plug in the boat and it began to fill, until a sailor removed his shirt and jammed it in to the drainage hole. The boat passed the stern of the Morro Castle, and Miss Conway noted that the passengers and crew gathered there were waving to them. The oars were soon lost overboard, but the crew hoisted a sail and #10, with fewer than 15 people in, it set off for the clearly visible shore.

Among the passengers waving at the occupants of #10 as it passed the stern of the liner, were Alexander and Frieda McArthur. They had gone aft on C Deck, and after the electricity failed, observed that the center of the ship was glowing. They remained on the C Deck fantail for perhaps ¾ of an hour, and when conditions became intolerable there, went down a deck to the small open area at the rear of D Deck at the orders of a crewman. Conditions on D Deck were as bad as they were on C. It was crowded, and waves of smoke choked the people who were trapped there. The McArthurs waited for orders, but none came. Mrs. McArthur noticed boat #10 as it passed. She hoped others would come, but they did not. The smoke continued to thicken and passengers began to go over the side. Alexander McArthur insisted that they jump, and although Frieda did not want to, there seemed to be no other options, and so she went. The couple held on to one another in the water, and while they were still in the circle of light from the burning ship, noticed their friends, the Wackers, in the water near them. But, the couples soon lost sight of one another as the wind and tide carried them away from the ship into the pre-dawn murk.

James and Ellen Kennedy watched the lifeboat, while it was still plainly visible in the light from the burning ship. She could see the white suits of the crew. Passengers and crew at the stern called its occupants, who seemed to Mrs. Kennedy to be rowing for dear life. They saw another boat off to the side of the Morro Castle, but it did not stop, either. The Kennedys had gone first to B Deck, where they observed that the smoke and fire would change directions as the ship moved with the wind. When B Deck became uninhabitable, the Kennedys went down to C Deck, where Ellen felt they were caught like rats in a trap. They could see the lights of New Jersey off to the left. At some point, James Kennedy, who could not swim, gave his lifebelt to a young girl who did not have one. As the smoke began to choke them, James grabbed his wife, kissed her, and then lifted her over the rail and dropped her.

Israel Rudberg watched #10 lowered from further back on the boat deck. The gymnasium was beginning to burn, the amidships portion of the deck was blazing fiercely, and he noted that the flames would change direction as the ship drifted with the wind and tide. No one seemed to be in charge. He observed that people were jumping from both A Deck and B Deck, and that in many cases their life preservers came off as soon as they hit the water. Once the gymnasium was afire, he climbed down to B Deck. B Deck was crowded, smoky, and as lacking in leadership as A Deck had been.

Ramon Ferner

18 year old Ramon Ferner, of Lyndhurst, New Jersey, had gone to sea to work as a wiper aboard the Morro Castle after graduating from Lyndhurst High School. On the night of the fire, he found himself forward on the starboard side of A deck, where crew members manned hoses, pulled trapped passengers from the windows of the deluxe cabins lining the boat deck, and prepared the lifeboats for lowering. Ferner was among the group of crew members, and three passengers, who entered lifeboat #1. The davits aboard the Morro Castle were automatic, and boats could be lowered without the need for a crew member to remain behind on deck. However, #1 jammed in its falls soon after lowering commenced, and Ramon Ferner climbed back aboard the ship to free the boat. What happened next was described by nearly everyone in #1 in their testimony, with some giving brief, abbreviated versions and others becoming quite graphic. Ferner, in blue overalls, attempted to climb down to where boat #1 waited, either by rope or rope ladder. At a point about halfway down the side of the ship, he either lost his grip or jumped for the boat and missed. Ramon was not wearing a life preserver and did not know how to swim. He floundered, and screamed for help. Boat #1, which had been carried astern and seaward of where Ferner struggled, awkwardly attempted to come to his aid, but by the time progress was made, he had vanished. True- the oars were awkward. And, true- there was a swift current running. But, two points cannot be overlooked. On a night where 67 year old Minnie Likewise successfully swam to safety against the wind and current, none of the men who wore life preservers and watched Ramon Ferner drown perhaps ten yards from their boat even attempted to swim to him. And, lifeboat #1 had a motor.

Eva Fisk, of New York City, and her cabin mate, Miss Frances Spector of Brooklyn, jumped from the Morro Castle together. There was only one lifebelt in their cabin, and Miss Spector never found one for herself before smoke forced the two women overboard. A lifeboat, under control, appeared from out of the storm, and Miss Fisk never forgot the moment when a crew member in the boat made direct eye contact with her as they passed without slowing down. Frances Spector, without a lifebelt, weakened and drowned.

Mrs. Catherine Phelps, of New York, survived to testify that as she was struggling in the storm, lifeboat #1 passed close enough to her that she was able to clearly recognize Chief Engineer Abbott, whom she had met during the voyage, in his white uniform.

Eleanor Brennan‘s party came to a disastrous end. The knock at her stateroom door was not room service, as expected, but someone who called out ‘fire’ to the partygoers. Eleanor ran aft with Helen Brodie and Agnes Berry to their cabin, C-273, to grab their life preservers, accompanied by Father Egan. They ran into cruise director Herman Cluthe in the aft lobby by the Barber Shop. He told them to be quiet. They smelled smoke but saw no fire. The four climbed up to B Deck.

Eleanor Brennan

They found B Deck to be a mass of flames and screaming people. They climbed down again to C Deck and to what Helen would later describe as bedlam. Two members of the crew were fighting the fire with buckets. Some of the passengers were hysterical. From the rail, the three women watched a lifeboat row along the side of the ship perhaps 8 feet out. It did not stop. Father Egan gave Conditional Absolution and the three women, all Catholic, drew close to him. Later, Helen would describe him as being the only calming influence on the deck. Some members of the crowd screamed ‘Jump! Jump’ while others screamed out not to. The heat increased and the smoke choked them and burned their eyes. Eleanor, Helen and Agnes climbed the rail and jumped together. The impact tore them apart from one another, and the 35 mph wind carried each woman away, alone, into the dark. Helen Brodie drifted, for several hours. She came across Eleanor Brennan in the water, but by that time Eleanor was in terrible condition. She clung to Helen’s life jacket and on at least two occasions muttered that she could not hold on. An airplane, probably occupied by New Jersey’s Governor Moore, repeatedly circled them and dipped its wings. This was to indicate their location to the fleet of fishing boats that was working against time to save people who had been carried closer to shore than where the lifeboats from the three rescue ships were searching. Eleanor was exhausted, and her reaction to the plane circling close overhead was hysteria. A boat diverted course and approached Miss Brodie and Miss Brennan, led by the plane, but at the last minute a large wave swept over the pair and Helen felt Eleanor torn away from her. Within five minutes, Helen Brodie was safely aboard a rescue craft.

The Clemens Landmann family, in C-241, was awakened by their neighbors George Sivation and Henry Zimplinski from cabin 239. They heard neither the explosion nor an alarm, if any sounded in their part of the ship and their only warning came from the two men who pounded on their door and called to them that there was a fire. George Sivation, a pharmacist from suburban Philadelphia, would survive, while Henry Zimplinski would die of exposure. The Landmanns stopped to dress- they later estimated that it took no more than two minutes. Mr. Landmann would later recall that the hall was full of smoke and water, and that the fire was reflected in the water pooling on the floor. The Landmanns found themselves at the stern of B Deck, with a large number of other passengers. Clemens looked forward and saw the lifeboats hanging unused along the side of A Deck. When he asked a crew member when the passengers would be put into the boats, he was told that it would not be necessary- rescue ships were on the way. Within ten minutes, the fire had burned through the rear of A Deck, cutting it off from those waiting below on B and making escape by lifeboat seems impossible.

The Wackers and Marjorie Budlong jumped from the ship together. They had been ordered to C Deck by either cruise director Smith, or Assistant Cruise Director Cluthe, and remained there until the smoke became intolerable. They climbed the rail together, but someone pushing from behind knocked Marjorie from the ship, away from the Wackers. And so the family came up together in the water, but their friend was nowhere to be seen.

As the Wackers were struggling to stay together, Edward and Adele Brady were witnessing the most horrible thing either had ever seen. Soon after entering the water, they came across Ann Conway’s card playing friend from the voyage, Morton Lyon. He had broken his neck jumping from the ship in a life jacket, but the blow had not killed him instantly, nor had it rendered him unconscious. His head lolled, and he struggled to breathe. Mr. and Mrs. Brady held him until he died, and then released his body and he drifted away, kept afloat by his life jacket.

Dr. Francisco Busquet, Chief Radiologist of Emergency and Polyclinic Hospitals in Havana, his wife, Ofelia Hernadez, 34, and teenage daughter, Ofelia, were stunned and practically knocked out when their life preservers rammed up under their chins as they hit the water. Miss Busquet had been awakened by the noise of the fire. She and her parents had donned life preservers and, after leaving their cabin, heard the massive explosion commented on by many survivors. They stood together at the rear of C Deck and watched the storm, noticing that there were occasional flashes of lightning in the distance. When the smoke became too thick, the family jumped and were nearly killed by their life jackets acting as nooses. When all three recovered from the blows each took to the head, they joined hands with one another and waited.

Angelus Cortez D’Orn, a friend of the Busquets who had traveled with them several times in the past, narrowly escaped with her life from A- 16, the port side mirror image cabin to Rosario Camacho’s. Mrs. D’Orn was an American, from Columbus, Ohio, who had married a French citizen and settled in Havana. She traveled without her husband on this voyage. Her stylish Whippet dog stayed in her A Deck cabin~ the first room reached by the fire on the port side. Unlike Miss Camacho, Mrs. D’Orn did not have the advantage of being awake as the flames from the lounge blew back and upward on to A Deck. She apparently awoke as the fire entered her cabin. She escaped out the window, on to the boat deck, with serious burns on her face and arms. Her Whippet died in the cabin.

Roberto Gonzales, 13, occupied A- 18, the next room aft of Angelus D’Orn’s. Roberto should not have been aboard the Morro Castle. His father, Isidore Gonzales, was the general manager of United Fruit, Havana. Roberto’s parents wanted him educated in the United States, and so during the school term he lived with his uncle and aunt, Mr. and Mrs. Joseph Jova, in Newburgh, NY. The Jovas were socially prominent, and Roberto became popular among the younger set at the tennis court and pool of the Powellton Club. Roberto, and his cousin, Henri Jova, spent the summer of 1934 in Cuba. Isidore Gonzales arranged for his son and nephew to return to New York aboard a United Fruit vessel, the Quirigua, sailing for New York on September 5th but when they arrived at the pier it was to discover that a booking error had been made and only one of the boys could be accommodated. So, Roberto was switched over to the Morro Castle while Henri kept the original reservation.

Roberto had as little time to escape as Mrs. D’Orn. Within ten minutes of the fire’s entrance into the lounge, the aft corridors on A Deck were impassable. But, Roberto had an advantage the other passengers on A Deck did not. For some reason, his cabin opened on to the boat deck and not in to the hallway, the only cabin aboard the ship so equipped. He was only steps away from Boat #10 and so his chances of survival seemed good.

Two doors down from Rosario Camacho’s A Deck cabin, Mrs. Caridad Aguilera Saenz and her son and two daughters did not have the split second stroke of luck that spared Angelus D’Orn. Caridad was the wife of Dr. Braulio Saenz of Havana. A 1927 passenger list from the Olympic allows a glimpse of the Saenz family’s lifestyle: they traveled en suite, along with Caridad’s mother and brother, and the children’s nurse and a governess. The Saenz y Aguilera children were educated in Boston, and each year Caridad would accompany them north, usually traveling by train from Miami. Caridad and her daughters Margarita, (8) and Marta (11) occupied cabin A-23, while her 13 year old son, Braulio, occupied A-21. When the family awoke, it was to discover that their cabins were already on fire and they were trapped.

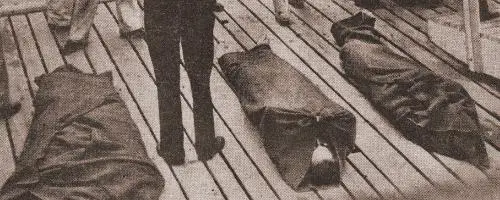

- ROADTRIP deckshots 5

- ROADTRIP deckshots 6

- ROADTRIP deckshots 4

- ROADTRIP deckshots 1

- ROADTRIP deckshot 8

Deck series taken from the location of the Saenz’s cabin.

Crewmember Malcolm Ferguson was manning a hose on the starboard side of A Deck, aft, when he was called to a by a steward. The steward had just pulled a horribly burned young boy from the window of Cabin A-21, and needed help carrying him away. When Ferguson took the boy in his arms, the child’s flesh came off in his hands. He carried the youngster, who he recognized from the dining room as Braulio Saenz y Aguilera, down to the enclosed section of B Deck. He laid the boy down and, for about ten minutes, manned a hose. When the electricity failed and the smoke began blowing back across the deck, Ferguson picked the boy up and carried him down to D Deck. While they were on the stairs, Braulio Saenz y Aguilera died. During the final half hour of his life he had said only two words, ‘Mi madre.’

Caridad Saenz burned to death in her cabin, where a few bones were later recovered from the floor. Marta Saenz y Aguilera, horribly burned on her face and arms, jumped from the ship without a life preserver. She wore a pink nightgown. She swam up to Steward Charles Wright, who bound her to his own life jacket. They drifted with a large group of other passengers and crew members, many of whom later commented on ‘the badly burned girl in the pink nightgown.’ Wright recalled that her face was scarred by the fire and that she was trying not to cry or whimper. She died after sunrise and Wright reluctantly let her body go.

* Photo of Morton Lyon courtesy of Williams College Archives and Special Collections, Williamstown, Mass., USA.

David Schneider crawled aft along A Deck under the smoke. At the top of the stairs between A and B Deck he found a burned Cuban girl who wore a plaid patterned silk dress. It had to have been Margarita Saenz. Marta wore a pink nightgown, and Schneider, who was in the textile business, was emphatic that the young girl wore plaid silk. There were no other Cuban girls quartered on A Deck, except for Rosario Camacho, and none of the three Cuban girls who survived the disaster were burned. He carried Margarita down to B Deck and then aft. From there, the burned Cuban girl vanished from his narrative. He later recalled that all he could hear was hollering and screaming. He ran in to Rosario Camacho, Franz de Beche and Joseph Hidalgo in the crowd and noted that only she wore a life jacket. The smoke was very dense, the deck was crowded and he later admitted to throwing people off. He was afraid that he would be crowded overboard, and so went from B Deck down to C and from C to D.

Clara Siegmond, 58, from Bardonia, New York, would later recount her most horrifying memory of the Morro Castle disaster as being the sight of the passengers trapped in midships cabins along C Deck forcing their way out of the portholes and tumbling into the ocean. Mrs. Siegmond, in cabin D-333, was one of the very few passengers to later mention hearing the ship’s alarm system sounding. She and her cabin mate, Miss Emily Beck, of Philadelphia, were awakened by a bell loudly ringing somewhere near their cabin. They dressed and went to investigate. When they discovered that the ship was afire, they took the time to return to their cabin and retrieve their pocketbooks. The electricity failed, and the two women walked forward toward the fire until they were directed sternward by a crew member. Both women were horrified by the confusion on deck and, as already said, by the sight of people trapped in their cabins struggling to save themselves. When the smoke began to make them sick, Mrs. Siegmond and Miss Beck slid down ropes from the stern, and clung to one another in the water as they were washed away from the ship.

Charles and Selma Filtzer remained on B Deck for as long as possible. Selma noticed that the direction in which the smoke was blowing changed. Sometimes it blew across the ship from port to starboard, while other times it blew aft. When conditions became suffocating on B Deck some passengers began to jump, while others walked down to C Deck using a crew stairway. The Filtzers went down the stairs of their own accord- there were no orders or instructions given by the crew as far as they knew. On C Deck the Filtzers felt as if they were going to be crushed or suffocated. People were climbing down from B Deck, climbing upward from the smoke filled confines of D and E Decks and emerging, at the last minute from the cabins along C. Smoke and ash and flaming flakes of paint blew back on the crowd. The heat seemed intolerable, and after about five minutes the Filtzers climbed the rail and jumped together.

Sidney and Dolly Davidson, of The Bronx, clung to one another as the storm carried them away from the burning liner. The Davidsons were on their honeymoon, and occupied the larger of the two cabins of suite 235/37, but in no accounts did either mention making the acquaintance of their suitemate, Eleanor Brennan. They were awakened that morning by shouting and the sound of people running in the corridor outside of their room. They ran to the C deck promenade, where a man helped Dolly overboard, and from where Sidney jumped.

The Davidsons swam together to a group of perhaps 25 passengers clinging to one another some distance from the ship. For the rest of her life, Dolly would remember one specific member of the circle-a little girl in a pink nightgown, with long black hair, who was burnt all over. Dozens of corpses drifted by the group, and Dolly found herself repeating “I won’t die! I won’t!” as the current carried the group towards shore. The passengers and crew joined hands, and sang for a time, to keep occupied.

Clemens, Jose and Marta Landmann found themselves trapped by thick, choking, waves of smoke. They had gone below to C Deck when conditions on B Deck worsened. A small semblance of order was observed by Clemens~ women and children were escorted below first. A few minutes later he climbed down as well, and found his family. The smoke poured back, directly over them. He noted that it was thick and black. The cabins only a few feet from there they stood were beginning to burn, and so he helped his wife and daughter over the rail, joined them and they pushed off from the ship with one another.

Abraham and Harriet Cohen and the Vitales were trapped at the rear of the crowd on C Deck, where the smoke and the heat were worst. The Cohens noticed that a portion of the crowd remained calm by singing ‘Hail! Hail! The Gang’s All Here’ but those furthest from the rail were beginning to become demoralized. Abraham recalled a crew man standing nearby and crying. The Cohens’ eyes burned and they felt themselves choking, so Abraham grasped Harriet by the shoulders and they pushed their way into the crowd, towards the rail. They jumped, and were momentarily stunned by the impact. Then they found one another in the water. Abraham’s life jacket was not fitting properly, and they swam to a group of passengers who were clinging to one another. A man helped adjust Mr. Cohen’s life preserver. The group soon drifted away, and the Cohens were alone. They saw no one else from the ship, alive or dead, near them in the water.

Loreta Hassall

Ethel Hassall

Loretta Hassall watched a lifeboat, with perhaps 25 people in, it pass about 200 yards from the ship. She found her parents and sister in the crowd, and they stood together on B Deck. Two other lifeboats passed by them, at five minute intervals. The boats rounded the stern, did not stop to pick up passengers, and rowed towards shore. It seemed to Mrs. Hassall that the boats were in control. Mr. and Mrs. Hassall, and Ethel, jumped from B Deck at about 3:40 when the smoke became unbearable. They were separated by the impact and swept away from one another. Loretta Hassall climbed down to C deck, and remained there until 4 AM, when the heat drove her overboard.

George and Charlotte Whitlock watched flames pour out of the doors and windows directly behind them on C Deck Two crew members threw streams of water at the fire from hoses. A man fell unconscious to the deck. Passengers and crew climbed on to the rail so that they could breathe better, hindering access for those behind them. Many of those who climbed on to the rail were pushed over by others desperate for air. There was no command or order to jump, but the smoke was so thick and choking that many did, anyway. The pressure to the hoses, which had been weak to begin with, tapered off and finally the streams of water ceased entirely.

The Jakobys and their friends stood in the crowd aft on B Deck. The smoke was thick and choking and the deck heated up under their feet. For a time, crew members and passengers were “helping” others by lifting them up and throwing them over the rail. Marie Renz became the first from their party to die. She was not wearing a life jacket and could not swim. Despite her protestations, and those of Mr. Renz, she was picked up and tossed overboard by would-be rescuers, and she immediately drowned beside the ship.

Henry Jakoby, Jr. helped his mother over the railing. They stood beside one another on the outside of the rail. They apparently slid down one of the ship’s lines, and the impact with the water injured Mrs. Jakoby’s spine. She noted that the water was cold and that it was still raining. Henry Jr. kept her afloat as they swam away from the liner.

Cabin Key belonging to the Featherstone Party (courtesy of Rich Romano)

Betty Sheridan of Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania, waited with her brother, Thomas Featherstone, and her eight year old son, Arthur, on one of the enclosed decks at the stern. She had been awakened by the smell of smoke in her cabin, C-261, and roused her brother and child. She dressed herself and Arthur, partially, and stepped out in to the corridor, where it seemed that everyone was screaming. All three took their life preservers and headed aft. For a time they were on B Deck, and then went lower to escape the heat and smoke. There were no lights, and Arthur began to smother. She stood him on the railing where he could breath, and when conditions continued to worsen she pushed him overboard and leapt after him.

For the Reuben Holden family, the situation must have been particularly appalling. They were not supposed to be aboard the Morro Castle. They were originally booked aboard the older, considerably less deluxe Ward Liner Orizaba’s August 29th sailing and, by the morning of September 8th, should have been at their Michigan Avenue home in Cincinnati. Their change of plans was so sudden that their names remained on the Orizaba’s voyage manifest, with a notation “Failed to board” appended. Mr. and Mrs. Holden traveled in the Morro Castle’s best cabin, C-238 while their sons John Morgan, 12, and Reuben Andrus, 16, shared C-245. The Holdens were awakened by the reflection of fire outside of their porthole. Mr. Holden roused his sons, and the family went aft together. Grace Holden remained calm, and when the smoke drove the family overboard she took the time to kiss each of her boys and tell them ‘Remember. If we get separated in the water we’ll all meet at the Roosevelt Hotel.’

James Borrell

Henrietta Borrell

Dr. James Borrell and his wife, Henrietta, stood at the stern of the Morro Castle and watched the fire advance towards them. Dr. Borrell was the president of the Erie County Medical Society, in Buffalo, New York. He and Mrs. Borrell had decided on a spontaneous and romantic vacation, and left Buffalo in their automobile at the end of August with no definite plans other than to drive to New York City. They wanted to take a cruise to either Cuba or Bermuda, but also discussed a New England motor trip or simply remaining in Manhattan for a week. They chose Cuba, and left their car parked at the Biltmore Hotel garage when they departed aboard the Morro Castle on September 1st. Mrs. Borrell carried over $3800.00 worth of diamonds with her. They occupied cabin C-259.

A steward’s knock awoke Dr. and Mrs. Borrell. When they fled their cabin, flames were already visible in the hall. They stood at the stern for almost an hour, until conditions became unbearable. The Borrells argued about who should jump first. Dr. Borrell wanted Henrietta to jump, and he would follow her in and find her once he knew she was safely off the ship. Henrietta wanted him to jump, and she would follow knowing that he would immediately swim to her once she was in the water. A crew member ordered them to jump, and they climbed the rail together. Henrietta went first, as it turned out, with her husband following. He could not find her in the churning water and was soon carried away from the ship, alone.

Henry Strauch

Dr. Henry Strauch, 41, and his wife, Ruth, 24, were also aboard the Morro Castle because of a spontaneous decision. Henry Strauch worked as a pharmacist as a young man and from there entered Thomas Jefferson Medical College in Philadelphia. He graduated, at age 35, and while serving his residency at West Penn Medical Center met young nursing student Ruth Rose, of Donora, Pennsylvania. Ruth was from a large working class family ~ her father was employed by a mill ~ and was eager to make her way in the world. Henry and Ruth married in 1930, after which he established his practice in her home town. They planned a sea vacation for themselves at the end of the summer of 1934, but could not decide whether a voyage to Bermuda aboard the Monarch of Bermuda, or a cruise to Nova Scotia, was the more appealing vacation. Henry took a business trip to Pittsburgh, and while there spontaneously booked himself and Ruth aboard the Morro Castle bound for Cuba. Ruth sent a letter and several postcards home to her family while the ship was in Havana. Her mother received a note written on Ward Line letterhead and dated September 2, in which Ruth wrote glowingly of the good time she and Henry were having and of her plans to attend the masquerade ball that evening. Dr. and Mrs. Strauch died in the disaster, leaving Ruth’s happy postcards home as the last record of the couple. Their cabin, A-19, was between those of Miss Camacho and Braulio Saenz, in the stern starboard corridor on A Deck. But, when Ruth’s father and brothers identified their bodies neither had been burned, indicating that they were likely still awake and not in their cabin when the fire swept into A Deck. One wonders if they were still alive at the point when the Monarch of Bermuda – the liner they could have been aboard ~ arrived on the scene at daybreak and anchored perhaps 100 yards from the burning Morro Castle.

James Coll*

Dr. James Coll, 50, head of the Modern Medical Associates Clinic in Jersey City, New Jersey, was aboard the Morro Castle with his wife, Dorothy, 23, and his guests Dr. and Mrs. Jules Blondiau and George Watremez. Dr. Blondiau had worked with Dr. Coll before relocating to Philadelphia and his cousin, George Watremez, 18, continued to work for Dr. Coll as his chauffeur. The traveling party occupied three widely spaced cabins and, oddly, James and Dorothy, who paid for the excursion, occupied the least desirable of them. Stateroom 328 was one of a group of three deluxe cabins set into the middle of the ship’s “low rent district” on D-Deck: the cabins were an entirely enclosed unit that had no access to D Deck and could only be reached or departed from by means of a single small flight of stairs up to C.

Dorothy Coll later remembered that George Watremez came to their cabin to awaken them. The electricity failed while they were still on D Deck, but they found their way up to the stern of C Deck where they met Dr. and Mrs. Blondiau. There was much pushing and jostling and no direction, and the crowd forced Mrs. Coll away from her husband and friends. She freely admitted to becoming ‘hysterical,’ for she could see her husband through the smoke and crowd, but could not reach him. She watched as he jumped from the ship. When the fire worsened and the crowd thinned a bit, Dorothy made her way to the rail and jumped as well.

Dr. Jules Blondiau and his wife, Martha – nicknamed “Margie”- were awakened by the panic in the hall outside of their cabin. They grabbed their life jackets, and Martha took her silver fox stole, before they fled for the stern. Martha had been a singer with an orchestra in New York City. She and Jules met in a nightclub and were married in a civil ceremony within a week. Despite the roaring twenties flavor of their courtship and wedding, the marriage worked. They ran into Jules’ cousin, George Watremez, who was coming down the corridor to find them and, later, when he returned with Dr. and Mrs. Coll, the touring party was briefly reunited. Dr. Blondiau later recalled Dr. Coll remarking ‘It’s going to be tough.’ He and Martha also recalled the crowd singing ‘Hail! Hail! The Gang’s All Here’ to bolster spirits as the fire moved closer.

George Watremez recalls the scene aft on B and C deck as being hellish. He woke up that night to see the reflected light of the fire outside of his porthole and hear the panicked crowd outside the door to his cabin, C-277. He describes Dr. Coll as being a nice man and a good employer, who was also a binge drinker. Dorothy Coll was a good person, who he remembers as being a farm girl from the vicinity of Fort Dix, New Jersey. Of all of the Morro Castle’s passengers, it seems that Dorothy Sooy Coll’s origins were the most humble. The 1930 census for Browns Mills, New Jersey, shows the Sooy family as being the only one on a list of neighbors nearly two pages long in which members were employed and had listed occupations. How she came to Jersey City, and met and married the Doctor is unknown, but George Watremez remembers that James Coll would affectionately introduce Dorothy as his ‘fifth wife’ (which she was) to which she would pointedly add ‘and your last wife.’ George delayed his escape to the open deck in order to make sure that the Colls were awake and free of their all-but-inaccessible cabin. Once on deck, he was soon separated from his boss and his cousin. He went up to B Deck, and watched the superstructure burning forward of where he stood. Passengers were jammed tight together, and many were beginning to remove their outer clothing and shoes, preparing for the inevitable jump. George did not know how to swim, but had a life jacket. When conditions became intolerable, he jumped from the area of B deck closest to the liner’s stern flagpole.

Anne Behling would later recall jumping for her life from beside the B deck flagpole as well. She had been one of the first passengers to arrive on the sports area aft of the gymnasium on A deck, but soon dozens of passengers and crew swarmed up from below and crowded around her. She observed that the crew members who arrived on A deck seemed to have just rolled out of their bunks and were adjusting their clothing. From where she stood the whole forward end of the boat seemed to be on fire. The lights of the Jersey shore were clearly visible. The Morro Castle was still under way.

When the smoke on A Deck grew too thick, Miss Behling went down to B Deck, where she found perhaps one hundred people, confused and excited, jammed together. There was no one instructing the passengers on what to do, but she did observe that one hose was being worked on the port side of the deck. Two lifeboats passed while Anne watched. One seemed very crowded while the other did not, and both quickly disappeared into the darkness. The volume of smoke pouring over the crowd became so great that Miss Behling began to feel as if she was in danger of suffocating, and so she climbed the rail beside the flagpole and jumped, pushing herself away from the ship.

Lillian Davison

Lillian Davison, a vacationing nurse from Columbia Presbyterian Hospital in New York City, was awakened by pounding on the door to the cabin, C-266; she shared with fellow nurse Martha Bradbury. Smoke was entering the room through the open porthole, and they could hear shouting and screams from the hall. Lillian had been on her own since 1926, when she survived a railroad crossing car accident that killed her father, Dr. Elwyn Davison, her mother and her brother. Bedridden for a year, she pushed herself to recover. By 1934, she had been working as a nurse for over a year. She and Martha were due back on duty at one in the afternoon of September 8th and so, presumably, had retired early. Whomever pounded on their door called out ‘Put your life jackets on and be ready!’ The two, knowing it was an emergency, reacted calmly, placing their life preservers on over their nightgowns and walking aft to the open area at the rear of B Deck. Lillian noted that at the time they arrived on the sports deck there was no panic- just a sense of urgency. When the smoke began to choke those who waited on B Deck, Lillian and Martha were among those who were ordered to go below and try to make their way forward. The intense heat, smoke and flames made it impossible to enter the ship on C Deck. No attempt was made to go forward. The two friends joined with the crowd of passengers who stood on the C Deck fantail and sang ‘Hail! Hail! The Gang’s All Here’ as the smoke began to thicken and the small aft lounge began to burn.

Rosario Camacho

Rosario Camacho separated from Marjorie, Doris, and the Wackers before they jumped from the ship. Cruise director Smith ordered her down to C Deck, where she met her friends Franz Hoed de Beche and Joseph Hidalgo. Joseph, 19, was en route to Lehigh University, in Pennsylvania, while Franz, 18, was returning his aunt’s apartment on West 116th Street in New York City, where he lived while attending De Witt Clinton High School. The two shared a cabin with one another, and like so many others, had been awakened by a pounding on their cabin door. After looking out of their porthole and seeing the upper decks of the ship in flames, they grabbed life preservers and headed aft to the open deck. Each wanted to give Rosario his life preserver, and Franz prevailed. He was a champion swimmer in both Havana and New York City, and felt that of the three he was best able to survive in the water without one. He and Rosario set out to find another life jacket, and Joseph Hidalgo went down one deck to the open area at the stern of D Deck. Rosario and Franz encountered an officer on C Deck. Rosario asked the officer when the boats would be lowered and he answered ‘God only knows, madam, don’t get upset.’ Smoke poured out of the doors leading out from the superstructure, choking the two young friends. They went towards the rail together, but their way was blocked by a large man who was able to lean out and breath relatively fresh air. They pulled at him, but he would not move. Rosario felt that she was about to suffocate, and bit the man on his upper back. He whirled around, and she and Franz de Beche pushed past him and climbed the rail. They planned on holding hands and jumping, but before they could, somebody struck them from behind and they fell from the ship separate from one another.