Morro Castle, Mohawk and the end of the Ward Line : Part 4

Another unlucky Ward Line ship. the Mohawk.

Interlude

In January 1935, as salvage crews worked to remove the Morro Castle from the beach at Asbury Park, the Ward Line’s Havana set sail from New York with a light passenger load aboard. She was destined not to complete her voyage, and ‘though her mishap seemed relatively minor when compared to the tragedy of the previous September, it set the stage for a second major disaster.

The Havana, which dated back to 1907, was not a particularly luxurious ship and was not in the same league as the Oriente in terms of interior design or amenities. However, she had reasonably spacious interiors and offered solid comfort without ostentation. She sailed for the Ward Line for ten years, then served as the hospital ship USS Comfort 1917-1925. Repurchased in 1927, she returned to passenger service in 1928 with one of her original two stacks removed and her interiors modernized and upgraded. In the Line hierarchy, she was third tier almost from the beginning of her renewed service, with Morro Castle and Oriente unquestionably the flagships after 1930, and Siboney and Orizaba placed behind them. Havana was not a headline grabber during her final seven years under that name, but was instead a dependable and affordable — important in the depression years — unit of the Ward Line fleet.

Three days our from New York, en route to Havana, Cuba and Veracruz, Mexico the Havana grounded on Mantilla Reef north of the Bahamas at 3:40 AM on January 6th 1935. She sat solidly aground, in clearly marked shoal waters, within sight of a buoy which marked the reef, being battered by high seas and by 6 a.m. was holed and taking in water. A distress call was sent out, and help soon arrived in the form of the Oriente as well as the Coast Guard cutters Vigilante and Pandora. The majority of the passengers -37- were rescued by the Miami bound El Oceano. However, during the evacuation a passenger, R.W. Rittenhouse of Brooklyn died of “apoplexy” and two – possibly three – other persons were missing after being swept out of a lifeboat by high seas. The following afternoon, as seas moderated, observers on planes that circled the stranded vessel reported that the 85 passengers and crew who remained aboard the Havana were nonchalantly playing shuffleboard or lounging on deck awaiting rescue. Among the crew was Morro Castle survivor Charles Wright.

Havana remained aground for three months. When finally freed, she was repaired and renamed Yucatan before her return in June 1935. She remained in the service of the Cuba Mail Line as a passenger ship through 1940, at which point she was converted to a freighter. She sank at her NYC pier later that year, was raised, repaired and renamed AGWILeon. She served during World War 2 as the hospital ship Shamrock and was finally scrapped at Oakland, California, in 1948.

Several crewmembers who survived the Morro Castle disaster were aboard the Havana when she grounded. AGWI, the parent company of Cuba Mail Line, transferred Clyde-Mallory’s Mohawk to Ward Line service to fill the double gap created by the loss of the Morro Castle and the disabling of the Havana. These men, among them Charles Wright whose account was given in the Morro Castle segment of this site, boarded the Mohawk on her Ward Line “Maiden Voyage” not imagining that their service with her would end disastrously in less than six hours and almost within sight of the Morro Castle’s hulk.

Iroquois Passenger List

Iroquois grounded

Taking Water Fast

Taking Water Fast

Clyde Mallory’s Mohawk commenced her Ward Line maiden voyage on Thursday, January 24, 1935 from Pier 13, East River, at the foot of Wall Street. The tail end of the worst winter storm of the year, a blizzard that dumped 17 inches of snow on Manhattan, was dispersing and the weather remained dismal ‘though clearing through the day. Passengers who traveled in to Manhattan by private car or cab later spoke of interminable delays, particularly on the bridges, as the city struggled to dig out from under the atypically heavy snowfall.

All in all it was not a particularly festive sailing day, but it is likely that the passengers and crew were buoyed by the thought that they would soon be in sunny Havana or Mexico, or points beyond. Among those who probably watched the financial district skyline glide by from inside the ship, grateful to be warm and indoors as she made her late afternoon departure, were a prominent NYC architect and his socialite wife; a member of the British diplomatic corps traveling to his new assignment in Mexico with his wife, mother and two sons; a pair of sisters who were heiresses to one of America’s great industrial fortunes, and a party of students from Williams College en route to Mexico with their professor-mentor. There was a party of women from Mansfield Ohio beginning a 24 day vacation; a wife returning to her husband in Havana, and-although not brought to the attention of the passengers- there were the several Morro Castle survivors on the crew list.

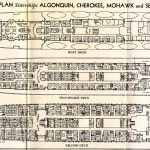

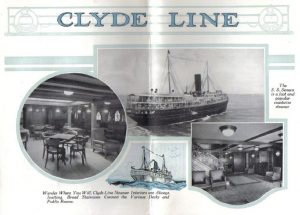

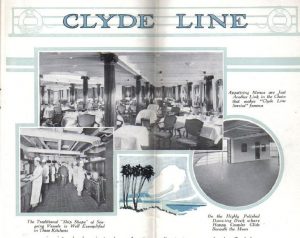

The Mohawk, part of a quartet of liners bearing the names of American Indian nations, was a single funnel vessel, measuring 402′ X 55′ and weighing 5896 tons. Her passenger accommodations and public rooms were spread out over three decks, with her lounge and dining saloon far forward on B and C decks respectively; her smoking room, deck verandah, barber shop and sun parlor at the rear of A deck, and a social hall amidships on B Deck. Her accommodations ranged from two room suites with private bath and toilet facilities, to minimum fare inside “upper and lower” cabins. Externally, the Mohawk could be described as sturdy rather than streamlined, and internally she was comfortable and, in places, quite elegant but by no stretch of the imagination could she be referred to as palatial. Photos show her furnishings to have been typical of what would have been found in upper middle class residences of the 1920s, and with her single deck public rooms scaled to her relatively narrow beam the overused adjective “homelike” was- for once- appropriate. Since her maiden trip in February 1926 she had earned a reputation for being a friendly and efficient ship, and those who embarked on her final voyage had no reason for trepidation.

An Earlier Mohawk Disaster

On January 2, 1925, Clyde Line’s original Mohawk was destroyed by fire at the height of a once-in-a-decade storm off the New Jersey coast . The crew battled overwhelming odds to contain the fire long enough for the ship to enter sheltered waters, and succeeded: she was scuttled in 40 feet of water inside of the Delaware Breakwater after her passengers and crew were safely evacuated. More…

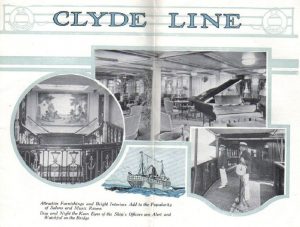

If the Ward Line ships of the late 1920s and early 1930s can be said to have been noticeable for the sheer volume of innuendo that swirled around them, then the Mohawk – class of Clyde Mallory Line vessels were outstanding for the sheer number of collisions – small and large- in which they were involved during their first decade of service (e.g. Cherokee). The two most notorious incidents took place in lower New York Harbor, and each involved one of the Clyde Mallory vessels to figure in the Mohawk disaster. The better remembered also involved one of the future heroes of the Morro Castle rescue fleet. Captain A.R. Francis, under the command of whom the crew of the Monarch of Bermuda played a pivotal role in the rescue of the Morro Castle survivors, and the Clyde-Mallory liner Algonquin, which played a pivotal role in the rescue of the Mohawk‘s survivors, crossed paths in a well-publicized and embarrassing incident in December 1929:

WALK DOWN SIDE OF SHIP AS IT SINKSFort Victoria’s Captain and Pilot Stick Until Water Reaches KneesHow Captain A.R. Francis of the rammed steamship Fort Victoria and her pilot walked down the ship’s side as the vessel sank was told today by J.C.B. Eustice, senior radio operator. Eustice was one of the 12 members of a skeleton crew who with the captain and deck officers remained aboard the ship in hope of beaching her. The ship, however, turned on her starboard side and sank, the crew having just enough time to get away in a lifeboat. The deck officers tarried a while longer and then plunged overboard. With water swirling over the deck to their knees the captain and the pilot, said Eustice, walked down the side into the water. They and the deck officers were picked up by the tug Columbine. |

Much of the United States was battling the Blizzard of the Decade on December 20, 1929, with 25 deaths across the American West, 60 MPH winds bringing Great Lakes traffic to halt and rendering air traffic impossible, as the Furness-Bermuda Line’s Fort Victoria and Clyde-Mallory’s Algonquin departed their respective piers for Bermuda and Miami/Galveston. Thick fog blanketed New York Harbor, and although the blizzard had not yet arrived, heavy sleet was falling. The Fort Victoria, after sailing at reduced speed to Sandy Hook, was halted near the lightship to drop pilot when the Algonquin, not legally required to depart under pilot, loomed out of the fog and rammed her on her port side just forward of amidships. Fort Victoria’s passengers were safely evacuated by tugs, and taken to Staten Island or back to the Furness-Bermuda pier, and an unsuccessful effort was made to lash the listing ship to the Algonquin. An equally unsuccessful effort was made to tow her into shallow waters, but she slowly capsized and sank. Fortunately, there were no lives lost.

A year and a half earlier, the Mohawk endured her first bout of unwelcome publicity when she became the most seriously damaged of six liners to collide in Lower New York Harbor while moving through a thick fog. The incident was treated with borderline amusement by the newspapers, for there were no deaths or serious injuries. Holland-America’s Veendam and the Bull Line’s Porto Rico collided near Gravesend Bay, Brooklyn and although early radio messages from the Veendam seemed dire, with water entering her engine room, her crew managed to stem the flow and the following day she sat anchored in Gravesend Bay, damaged but in no danger of sinking, while the Porto Rico was beached in the shallows nearby. The Pennland was struck by the smaller Anniston City, near Sandy Hook, with both ships seriously damaged and taking on water but surviving. The excursion vessel Smithfield, off course in the fog, ran aground with little damage. And, as for the Mohawk:

| The Clyde liner Mohawk, which collided with the Old Dominion liner Jefferson, made for a New Jersey Beach in the lower bay, her distress whistles screeching above the incessant hooting of fog horns. She went aground near Atlantic Beach, her captain asking the Coast Guard to come to her aid. She carried 85 passengers and was bound for Jacksonville.

Owing to light wind and seas none of the vessels were believed to be in immediate danger. The Jefferson, inbound from Norfolk, Va. reported her stem severely wrenched and her forepeak flooded. The only vessel sending out an SOS was the Mohawk. |

The Mohawk, grounded parallel to the beach, and less than her length offshore, was evacuated the following day. Photos show the passengers smiling as they were disembarked by lifeboat. Because of the proximity to a public beach near New York, the stranded ship became the subject of hundreds-if not thousands- of press and private photographs before she was towed away for repair work. The event was well publicized but certainly not earth shattering and it is doubtful that any passengers aboard the Mohawk in 1935 gave it any thought as the liner passed the site of the collision near Sandy Hook.

Small fragments of what went on aboard the Mohawk during her final six or so hours of life can be gleaned from survivor accounts. The liner lost several hours of voyage time when she paused to adjust and test her compass once beyond Sandy Hook. A “pleasant,” but delayed dinner was served. The passenger compliment was described as “congenial.” The door connecting the lounge to the enclosed promenade deck did not fit snugly and there was a noticeable cold draft along one side of the room. Little was later said with regards to the liner’s décor or physical layout: the passengers were not aboard her long enough to retain detailed memories of her public rooms and, in truth, the Mohawk simply was not the sort of liner to cause passengers to wax rhapsodic, although a handful later did describe their accommodations as being “comfortable.” Only two incidents from the Mohawk’s final night were widely reported: after sunset, and a short time before the accident, word was spread among the passengers in the lounge that Asbury Park was drawing abreast along the starboard side and a group of interested passengers left the heated comfort of the lounge to see if the hulk of the Morro Castle was visible across the five miles of water that separated the two ships. And at the moment of the collision the ship’s orchestra was playing “I Saw Stars.”

Shortly after 8:30 PM the lights of the Norwegian freighter Talisman became visible ahead, and to port, of the Mohawk. There was never any question that the two ships saw one another, and there seemed to be nothing out of the ordinary or dangerous in the situation: they were traveling in the same direction and on parallel courses. However, as the Mohawk drew abreast of the Talisman at 9:25, something went catastrophically wrong, and the liner veered suddenly, and at full speed, across the Talisman’s bow. The Mohawk listed severely to port, recovered, and listed severely again before she sank about 70 minutes after the collision. The evacuation was calm but not particularly well organized, the Talisman lowered no lifeboats to render aid, and the Mohawk’s passengers and crew lost valuable time freeing frozen lifeboats from their davits. The Algonquin, northbound on a freight voyage with no passengers aboard, and the freighter Limon arrived on the scene in time to sweep the sinking liner with their search lights giving those in the lifeboats, and those trapped aboard the Mohawk, a clear view of the final moments.

Mohawk Lifeboat

Jim Kalafus Collection

The best official account of the Mohawk’s collision and foundering was given at the United States Steamboat Service inquiry by her only surviving officer.

Chief Officer Cort Peterson began his time on the stand by explaining how it happened that the faster Mohawk was in a position to overtake the Talisman, which in addition to being slower had also departed from Brooklyn an hour after the Ward Line vessel sailed from East River Pier 13 in Manhatttan. The Mohawk, as it turned out, had been delayed in the lower harbor for over three hours while her compass was adjusted, during which time the Talisman had passed her. Peterson then moved on to the accident. He was in the Number 1 hold at the time of the collision, and ran on deck in time to see the bow of the Talisman pull out of and away from the Mohawk’s side.

As I reached the bridge, Captain Wood shouted “the steering gear is jammed; telephone the engine room. I want the ship stopped”

The line of questioning then shifted to the adjustment of the compass, and if the sharp changes of direction might have damaged the steering gear. Peterson spoke instead of going below to inspect the steering gear after the collision and of returning to the bridge where Captain Wood ordered him to prepare the lifeboats for lowering, and to warn the passengers.

Q: Was there any difficulty in lowering the boats?

A: Well, a bit, on account of the ice.Q: Did you get all the lifeboats off?

A: That I don’t know. There was no trouble on my side.Q: When the Mohawk was hit, did she begin to list immediately?

A: The list to port was very heavy. About 30 degrees.Q: That’s an awfully big list.

A: Well, you couldn’t stand on the deck. You had to slide. But, she righted herself slowly. Then there was a gradual list to starboard about twenty minutes later.Q: Did the Talisman carry away the wing of the bridge?

A: Yes, it was squashed in.Q: The telegraph was situated in the middle of the bridge?

A: Yes.Q: Did the damage to the bridge extend far enough toward the center to damage the telegraph?

A: I really think so.Q: Did the telegraph system fail before or after the collision?

A: (long pause) I don’t know. The collision happened when I went to the bridge.

Peterson then described the lowering of the boats. #4 on the port side got away first, followed by starboard boats #5 and #3. Peterson escaped in #2, which contained only twelve to fourteen crewmen.

Q: Were all the passengers gone?

A: As far as I could ascertain. We sent men aft to look for them.Q: Was there a search of the passengers’ quarters to make sure?

A: So far as I know.

With Captain Wood and all but one of the Mohawk’s officers dead, the highest ranking person to give testimony was Captain Edmund Wang of the Talisman:

The night was clear. The Talisman was headed to pass off Barnegat Light on her starboard, some fifteen miles ahead.

The Mohawk was observed a mile or two distant on the Talisman’s starboard quarter. She was overtaking the Talisman on the Talisman’s starboard side. The Mohawk was going much faster than the Talisman and drew abreast of her and then ahead.

As the Mohawk was drawing ahead, she suddenly sheered sharply to port and ran directly across the Talisman’s bow at nearly right angles. The Talisman at once reversed her engines and starboarded her helm, but the Mohawk came directly in front of her bows at high speed.

The Talisman’s stem came into contact with the Mohawk’s port bow forty or fifty feet from the Mohawk’s stem. The Mohawk’s speed swung the Talisman around to the east and the vessels parted.

The Talisman sent out wireless calls for help and messages were exchanged between the Mohawk and the Talisman. The steamers Algonquin and Limon came up and picked up those who were in the Mohawk’s lifeboats. A Coast Guard cutter also assisted. The Talisman stood by to give help, and remained all night cruising about and looking for survivors.

Questions immediately arose regarding the Talisman’s actions after the collision. Despite her close proximity to the foundering Mohawk, three ship’s lengths at the beginning of the liner’s foundering and less than a mile away at the end, she carried not a single survivor back to New York. Captain Wang was questioned at the United States Steamboat Service inquiry and his answers prove a disheartening contrast to his self- assured final paragraph above:

The captain of the Mohawk informed us over the radio that he did not want our boats lowered. We had our boats ready to lower and they could have been in the water in a couple of minutes.

The transcript of the radio record of the Mohawk’s final hour was then read into the record and there was no refusal of aid by Captain Wood contained in it. When the first exchange of radio messages between the two ships took place the Talisman was about three ship lengths way from the fatally injured Mohawk.

Q: Then you used your own judgment about lowering the lifeboats? I see nothing in these radio reports about any request by the Mohawk that you should not lower lifeboats

A: (Witness nodded assent.)The board then commented on how ‘queer’ it was that none of the 116 survivors were brought aboard the Talisman. Captain Wang explained that the arrival of the Algonquin, with her powerful search light gave the lifeboats something obvious to row towards.

Because of the light the survivors rowed towards that boat. They apparently did not see us.

Captain Wang also claimed that he heard no warning whistle signals from the Mohawk at any point before the collision. Testimony from quartermaster Edwin Johnsen who was at the helm at the time of the collision, and lookout Bjarne Johansen, was then read into the record contradicting the statement of Captain Wang. Both men swore that they had heard several short blasts of the Mohawk’s whistle immediately before the collision, and Johansen admitted to abandoning his post so that he “wouldn’t get hurt.” At which point Wang admitted that he knew that there was going to be a collision but did not specify how long before the crash he knew. “I was staying my course” he said, and then gave the additional detail that one of his officers made the comment “I bet his steering gear is gone!”

A portion of Mohawk look-out Frank Novak‘s account survives:

I shared the look-out with George Clancy. We were on the 8 to 12 watch, and we took half hour turns relieving each other. At 8:30 Clancy told me he reported lights off the port bow. I watched them and reported to the bridge that the lights were coming closer when I went off at 9.

At 9:25 I left my bunk in the fo’c’sle to ‘spell’ Clancy and got top-side just as the freighter hit us. I ran to the bridge for instructions and the skipper said to help at the life boats.

I dashed past my bunk on the way down and two of my buddies were stretched out in a passageway badly mangled. They were dead and I ran to the deck. We had a heck of a time with the davits because of the ice. We got three boats away and there were no more passengers around when the Old Man ordered us away in boat No. 4.

George Clancy testified:

Both vessels were headed south, the Talisman clearly visible in the distance off our port quarter. The night was clear, the visibility was excellent, the sea was calm and the cold was intense. We were proceeding at about fifteen knots and eventually we overtook and drew abreast of the Talisman.

Then suddenly, without warning, the steering gear went bad and we swerved across the Talisman’s course. The captain, seeing an accident was unavoidable, blew several warning signals telling the freighter to keep sharp to port. I guess the Talisman must have taken the signal wrong because it kept on coming for us and a minute later she crashed into our port side. The stem bashed into our fo’c’sle where the sailors were sleeping in their bunks. Some of them must have been killed in the crash.

The Mohawk began to take on water fast. Captain Wood ordered all boats lowered. Two boats on the port side went over and broke away from the davits when they hit the water and went adrift. The boats on the starboard side were lowered and the passengers and members of the crew were ordered into them.

There was quite a bit of excitement, and when the ship listed a number of people jumped overboard. I think all of them were picked up.

I remained on the bow of the boat until it began to sink. By this time the lifeboats were over the side. I had to jump overboard and was picked up in the water by boat #9. Captain Wood was still on the bridge as I went in.

The Mohawk sank within forty minutes after she was hit. We pulled away from her and drifted for about an hour before our boat was picked up by the Limon which had received a wireless message of the accident. The Limon then set our boat adrift as they had several others.

MOHAWK STEERING GEAR FAILED, RYE MAN SAYSNEW YORK. Jan. 29th The man who handled the ‘trick’ of emergency steering gear of the liner Mohawk the night it collided with the freighter Talisman testified today that, given a specific order of “15 degrees starboard” he would not know which way the ships’ rudder would turn. The only way in which he knew in which to carry out such an order, Stephen John Snyder, 31, of Blind Brook Lodge, Rye, Deck Engineer of the Mohawk tesified today at a Federal hearing, would be to move the bottom of the wheel “in the same direction as I moved the handle of the telegraph.” Just before the Mohawk careened suddenly from her course off the coast of New Jersey last Thursday night and into the path of the Talisman, her automatic telemotor steering apparatus failed, witnesses have told the inquisitors, and the ‘trick’ device was employed to guide the vessel. The change from telemotor to ‘trick’ steering was not made before the collision which sank the Ward liner so far as he knew, the witness tesified, adding, however, that it might have been done while he was engaged in tracing a glycerine line of the automatic steering system. |

Mary Pillsbury Lord, (1904-1978) future U.S. Delegate to the United Nations General Assembly (1958 and 1960) and U.S. Representative to the United Nations Human Rights Commission (1953-1961) and her sister Katherine Pillsbury McKee (died 1978) were aboard the Mohawk’s fatal voyage. Both survived, and a few days later Mary’s husband Oswald Lord wrote a narrative account of the sisters’ experiences which was meant to answer as many questions as possible to reduce the number asked of them during the weeks to come as they tried to forget the disaster.

After dinner Katherine and Mary went to the smoking room where the cruise director was holding a ‘get together’ meeting. When he had finished, Dr. Smith told a few funny stories and the girls were just thinking of beginning the books they had brought to the smoking room with them, entitled, ironically- “Heaven is my Destination” and “Heaven and Hell” when the engines stopped. Sirens blew and there was a jar sufficient to upset some of the glasses in the smoking room but not all.

The cruise director and the bar steward said there was nothing to worry about and then an officer came in and said they had been grazed by another vessel but that it was not serious. Many passengers left to see the other vessel but the girls, the Peabodys and Williams’ boys and a few others delayed a few minutes before going on deck. They could see the Talisman close by, and hear the men on its decks shouting to the Mohawk.

They returned to their state room and put their money inside their corsets, took their extra coats and furs, all the blankets they could find and a quart of whisky left behind from the bon voyage party.

They left their cabin and sat down at the head of the stairs leading to B Deck, just outside the smoking room. Other passengers were seated near them including the Peabodys.Mrs. Peabody (whom they knew by sight but had not spoken to) suggested “You two girls are alone. Won’t you come in our lifeboat with us?” They thanked her, but said they thought they should go to their own boats to avoid confusion. The Peabodys were lost.

When they returned to the head of the stairway the other passengers had left, having been herded down to B Deck to their boat stations. They could see them pouring through the doors to the deck below. They asked a member of the crew if they should go down to B Deck but he told them there were too many down there and to get out on the deck where they were A Deck- the boat deck.

The crew were working on the lifeboat just outside the door and cursing because they were hampered by the ice. It seemed that there was no one working on the next boat forward.

About this time, the boat gave a sudden lurch and listed violently to starboard. Thinking the boat was turning over a few passengers jumped overboard and the girls said goodbye to one another. The boat stopped at an angle of about 45 degrees and the crew continued to work at the lifeboats. The lights went out and a minute later the emergency lights- which were brighter- came on.

The Mohawk slowly settled back on an even keel. A crew member remarked that was a good sign. In reality he meant that the boat was settling, but it reassured the passengers.

Mrs. Lord and Mrs. McKee were placed into a lifeboat on A Deck. It was then lowered to its boarding station of B Deck and filled.

.it was announced that there was room for one more woman. She was put in, and then an Englishman- Mr. Telfer- handed the girls his five year old son to take care of.

There were three sailors, the Cruise Director, Dr. Smith, bath steward Ricca and twenty to twenty-five women in the boat. The tiller had been damaged, and soon all but one oar was lost overboard..something jammed at the bow tackle and that end remained a few feet out of the water. Someone produced an axe and a sailor hacked at the ropes. Meanwhile, the water was pouring through the port holes on C Deck and they were being buffeted against the ship..the axe fell from his frozen hands and was lost overboard..it was impossible to get away from the Mohawk as they were on the windward side.their boat was slowly blown forward along the side of the Mohawk and over its bow which by this time was under water. As they were blown in among the masts and cranes something fouled. They were caught fast to the Mohawk as she began to go under. There were cries for a pen knife and the girls stood up waving desperately in the direction of the Limon which was nearby and whose searchlight was on them. They are not quite clear what happened next. They remember seeing the smoke stack falling towards them and they think there was an explosion. Whether the smoke stack made a large wave or the explosion blew them clear they do not know, but they were washed out of the suction of the Mohawk.

A couple of minutes later the Mohawk went down with about ten people holding on to the rail at the stern, one of them they think was a woman.

Once they were finally free of the Mohawk the sailor at the tiller seemed to go crazy, took off most of his clothes and lay down in the bottom of the lifeboat saying he couldn’t help any more because he didn’t have clothes and begging Katherine to remove his life belt. Mary then took the tiller. Mary, Katherine, a Miss Weiss and one other woman helped taking turns at the one oar and the broken tiller.

They heard a cry for help and the two girls and Ricca pulled a man into the boat. Katherine sat on him to keep him warm and tried to rub back his circulation. They heard two other men crying for help but were unable to reach them.

After a while the searchlight of the Algonquin picked them up and they drifted to it and were taken in through a cargo port.

Mary, Katherine, the Williams boy and other survivors in the best condition then worked over the less fortunate.by four o’clock everyone was attended to. The two girls lay down in the cabin with the Telfer children. At six o’clock the baby awoke crying. After fixing him up as best they could Katherine went out to see where they were. When Mary returned from the washroom she found the five year old boy crying and praying for his parents. He apologized for his tears and said it wouldn’t happen again. This was the only time they saw him cry and they said he was very brave throughout the whole time. Both parents were lost.

Mary Pillsbury Lord was in the early stages of pregnancy when she survived the disaster. Her son, Richard Lord, was born on July 30th, 1935 and died on October 23rd of the same year. She had two other sons, Charles Pillsbury Lord and Winston Lord. Winston served as U.S. Ambassdor to China 1985-1989, Assisstant Secretary of State for East Asian and Pacific Affairs beginning in 1993, and as the co-chairman of the International Rescue Committee.

Algonquin

Mohawk Class Deckplans

I Saw Stars

Mohawk

The Yucatan Expedition

The Yucatan Expedition

Jim Kalafus and Mike Poirier

The best account of the Mohawk disaster, and one of the best shipwreck accounts in general that we have found, was written by 23 year old Karl Osterhout, a student from Williams College who, at the request of the school, set down a painstakingly detailed reminiscence of the disaster which claimed three of his classmates and their professor.

Outerhout, of Williamstown, Massachussetts, and formerly of Yonkers, N.Y. and New York City, was part of an expedition of Williams College seniors who intended to spend three weeks in Cuba and The Yucatan studying geology and archaeology. The first leg of their trip was the voyage from New York to Cuba, after which they would fly to Mexico. Joining Osterhout were William Dwight Symmes of Manhattan, Julius Palmer of Providence, Rhode Island, Roy Huth Myers from Pittsburg, Pennsylvania, Lawrence D. Rockwell of Smithtown, Long Island, New York, and Lloyd Houghton Crowfoot from Ashburnham, Massachusetts. Their leader, Professor Herdman Fitzgerald Cleland, 65, had published at least six books (the best known of which were Our Prehistoric Ancestors, and Why Be an Evolutionist?) and was a specialist on with the link between anthropology and geology as established through the archaeological record. According to 1935 newspaper accounts, the expedtion was funded by an anonymous donor.

What should have been the adventure of a lifetime instead ended tragically only six hours out from New York City.

Karl Osterhaut

Lawrence Rockwell

Roy Huth Myers

Lloyd Crowfoot

William Symmes

Julius Palmer

Memorial Gate

We begin Osterhout’s account on sailing day, in New York City. He had traveled down from Albany in the company of his friends Julius Palmer and Lloyd Crowfoot, and joined the rest of the expedition members at the Williams Club in Manhattan. The trip was to overlap exam week, and so the students took the first of a series of exams in the club dining room – the rest would be spaced throughout the journey.

When the examination period closed at twelve o’clock, I went to my room and finished packing. Then I went to Palmer’s room and visited with him while he shaved and packed. The evening before he had been out with Alice Greenwich, so he called her up to bid her goodbye, and she invited both of us to luncheon. I asked Dr. Cleland if it were all right for us to leave. He was lunching in the club dining room with Mr. Howard Scholle and said we didn’t have to meet until the boat sailed.

During the examination, Palmer had broken the crystal of his watch, so before leaving the club definitely, we went out to have it fixed. I bought a carton of cigarettes and two rolls of film for my camera. At about 1:30 we finally left the Williams Club and drove to Wall Street, where we met the Greenwiches and had luncheon. They were very nice people and insisted on buying a carton of cigarettes for Palmer. As we had about an hour before sailing time, we went up to Mr. Greenwich’s office on the twenty-fifth floor of a building in lower New York, and there we had our first look at the Mohawk. It looked very small from where we were. Getting more excited about our trip, we left and went on board. As Palmer and I planned to room together, we went directly to our stateroom, Number 112, and checked our baggage. From there we went directly to the forward part of A Deck and waved to Alice Greenwich and her mother in the building across the way. I ws surprised to see so much snow and ice in the corners of the deck.

(Professor Cleland) was much upset that Crowfoot hadn’t arrived yet, he said that would delay us and upset all our plans. However, just as the crew were about to take in the gangplank, Crowfoot arrived in a taxi. He told us he had instructed the taxi driver to drive him to Pier 13, and that the taxi had taken him to Pier 13, North River. Discovering, on their arrival, that it should have been Pier 13, East River, they drove at breakneck speed across the city, crashing all the red lights in order to reach the boat before it sailed.

As it was a very cold, blustery day, we didn’t stay long on deck after the two tugs started to ease the ship from the pier. We went inside to inspect the ship and only returned to the deck again to take a few pictures as we went past the lower point of Manhattan and the Statue of liberty.

.the lounge was very cool because the starboard door to the deck did not shut tightly.

.we headed for the dining room, only to be told dinner was not ready. We wandered back to the stern, and about midship we felt the boat start to rock as if it had stopped. It made walking difficult, but the rocking motion only lasted a short time.

Dr. Cleland told us how the ship managed its library and how he on all his trips had never had to pay the dollar deposit on a book. He also remarked that never before had he known dinner to be late.

.we decided to wait no longer for our meal, so we walked right in and were placed at our table, in the corner towards the bow on the port side.

Once during our meal the boat must have stopped, or we again noticed the rocking movement, which lasted about five minutes.

After our meal, we went to the club room , or bar, in the stern of the ship.Rockwell suggested cards, so four of us, Rockwell, Symmes, Myers and I bought two packs of cards and started to play: Roy (Myers) was my partner..Crowfoot and Palmer were writing letters nearby, and the ship’s orchestra was playing.

Dr. Smith told two or three jokes, but the interest turned from him when someone mentioned that we were passing the spot where the Morro Castle lay. Many of the more curious ran to the windows and peered out into the night in the direction of that ship.

Shortly after this, the Mohawk started to rock back and forth, as she had done twice previously, then there were there short blasts from a boat’s whistle.then came the crash. It didn’t sound like a big crash, but there was a sound like splintering wood. At the inapt everyone stood up simultaneously;. One woman screamed. Someone said “Here it is.” Luckett tried to get the band to play, but the men refused..

I immediately ran out on deck through the door on the portside of the main stairway known as the sun parlor. Looking forward, I could see a steamer in contact, or practically in contact, with the Mohawk…I hurried inside and down to my stateroom to get my coat, hat, gloves and muffler. When I came back on deck, I ran across professor Cleland, who asked me if I could make out the name of the ship.. It had pulled away from us about an hundred yards, and I could just make out its name–Talisman.

Upon going inside, I remembered my glasses, so returned to the bar, found them on the table, and put them in their case. I also picked up the two decks of playing cards, where they lay strewn about, and put them in their respective boxes and into my right-hand coat pocket..

Returning to the sun parlor, I met Dr. Cleland again, who told me to put my life preserver on and get a blanket in case we had to take to the boats. He already had both of these things.

When I went into my stateroom, there was Palmer seated on his bunk, writing in his diary and using the sink as a table. I threw the playing cards on the bunk, grabbed a life preserver and told palmer to do the same thing. As I was about to leave the room, Palmer said “I am writing in my diary exactly how I felt when the crash came.”

I again ran across Professor Cleland, and as I was putting on my life preserver he said to me “I wish this could have happened in warmer waters.” As I look back on that remark, I realize that Dr. Cleland knew then that we were in a serious situation.

Immediately after the crash our Williams party became separated, and we were never together again as a group. From time to time I ran into one or another of them in different parts of the boat.

I made my way to the top of the stairs, to A Deck. There was then a great crowd around the door and no chance of getting on deck. Ad the boat was tilted to port and down at the head, several people shouted for everyone to get to the starboard side to bring the boat on an even keel.

.I returned the way I had come, and met the five members of the Telfer family outside of one of their staterooms. This family consisted of Mr. and Mrs. Telfer, their two sons aged four months and five years, and Mr. Telfer’s mother. Mr. Telfer was having a difficult time getting his life preserver tied on, so I tied it for him. Then he asked me to help the grandmother, who had the four month old baby in her arms. The ship was at such an angle that it was very difficult to help her. The only thing I could do was get behind her and push her along the wall, as both of us had to lean against the stateroom walls to keep our balance. When we came to the end of the wall and into the sun parlor, we almost fell down, but we managed to reach the stairs and I forced her up by pushing with all my strength. The last few steps were the most difficult, as they were on such a slant. Several men were in front of the doorway onto the deck, but they stepped aside and let her through. My work with her ended when she went through the door. At this point I noticed two people, a man and a woman, seated on side seats in the sun parlor on A Deck. They were visiting, and not the least bit disturbed at the general commotion. They acted just as if it were a regular occurrence. The next day I learned that they were Mr. and Mrs. Peabody.

Shortly after, while standing on B Deck, I saw boats Number 3 and Number 5 come over the side. Both boats seemed quite full, and as the occupants in Number 3 shouted the boat was full, the men running it down from above did not stop it at B Deck. As Number 5 came down to deck level, several of us persuaded the occupants to take the elder Mrs. Telfer and the four months old baby, so with the aid of a man in the boat the young Telfer was handed over into the boat. He was all bound up in blankets and several of us feared that he might fall between the two boats, but the man in the lifeboat had a good grip and there was no accident. Both of these boats, number 3 and number 5 had a great deal of trouble getting away from the Mohawk. One was attached by the stern and they couldn’t seem to free it. One of the sailors in this boat called up to deck for an axe, but ti was lost over the side. This boat finally came free and pulled away.

At one point in my travels around the decks I remember seeing Professor Cleland having a polite argument with a stout man on A Deck. They were just going out the starboard deck and each was trying to persuade the other to go first. Gentlemen to the last.

.letting go of the railing, I fell flat on my back on the icy deck and was only able to pick myself up fifteen feet away from where I started. Everyone near by turned to see who was causing all the commotion. From here I started down the deck and came up behind Mrs. Telfer and her five year old son. She was leading the way and he was trying to keep up with her, and he must have been frightened for he began to cry. I tried to cheer him up by putting my hand on his shoulder and speaking to him. At this moment I saw a boat going over the side, but it was too far over that we couldn’t enter it from A Deck, so I picked up the child in my arms and, calling to Mrs. Telfer, headed down the deck, through a door, and down a very narrow flight of stairs to B Deck. Several men were coming up the stairs, but I called to them there was a child and a lady, so they got to one side. One thing that bothered me as I went through the door was to see a man coming out with a large brown suitcase in his hand. I carried the boy down the stairs and out on deck and passed him into Boat 7 from B Deck. The people already in the boat wouldn’t let Mrs. Telfer in, as they said there wasn’t room for any more. She became upset when she saw the boat being lowered into the water with her son in it, and said “I hope he will be all right.” I told her that he would be and putting my hand on her shoulder started to walk with her toward the stern. I was on her left side. As Mr. Telfer came up on her right side almost immediately, I left them. As I was going away, she thanked me. Both Mr. and Mrs. Telfer were lost.

A few minutes later, passing through the sun parlor, I was conscious of the sound of breaking glass. The noise came from the forward part of the ship, and must have been caused by the pressure of water against the forward lounge as the ship was going under. While I was listening, the ship came to an even keel and a feeling that everything would be alright from now on passed though my mind. But at that moment the lights went out, leaving us in total darkness: however, they came on again almost immediately. At that time there were quite a few people around the doorway into A Deck, and Mr. and Mrs. Peabody were seated in the same position as when I spoke of them before.

The next thing I remember was walking towards the bow on the starboard side and looking off in the distance at a ship with a searchlight. This ship was some distance from us at the time and headed our way with its searchlight directed on the Mohawk. Of a sudden, looking down, I saw water washing up to my feet,. It was around the forward lounge door, so that I could not have gotten to that door if I wished.

.just then two people joined me, a man and a woman who had come around from the stern. It was so dark that I was unable to recognize their faces. Further down the deck I saw several men trying to launch a boat, so, going back to the sun parlor door, I called for the rest of our crowd. Myers and Rockwell came, and the three of us headed down the deck towards that boat. As we came up, the men pushed it over the side and started to let it down. I hollered that we would have to go to the next deck to get it, so we started down the small stairs opposite the ones which I had carried the Telfer boy some time previous. I went down first, Rockwell was right behind me, and Myers was third. The boat was passing by the railing as we came out on b Deck, but it caught against the side of the tilting ship. Three men were in the boat by then, trying to rock it down. One of them was trying to clear the lifeboat from the main vessel by using an oar as a lever between, but as he couldn’t get any leverage, I climbed over the rail and , leaning over the side, tried to guide the oar handle into a porthole to give it leverage. The boat was lowered slowly by this method, and all the time we were working on it people from above were throwing suitcases and luggage into it. Most of the luggage broke open when it

i landed and scattered things over the bottom of the boat. When the lifeboat finally hit the water, we all jumped. I landed in front of the boat and immediately, with the aid of two sailors, tried to release the frozen chocks. Finally, after what seemed like a long interval of time, our end came loose and swung away from the sinking Mohawk. However, the other end would not seem to come free and there was a great deal of shouting going on. At this time the ship was well over on its side. Our lifeboat would drift away as far as the davit ropes would let it, then a wave would catch us and drive us up against the bottom with terrific force. This happened three or four times before the other rope was finally loosened and by the aid of wind and oars we got away, off the port side and stern of the sinking ship.

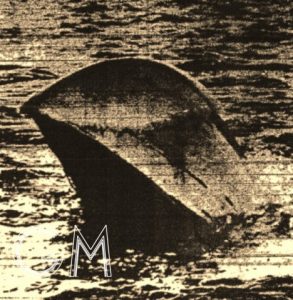

When we were about fifty yards away, we could see the lights of another ship playing on the Mohawk, and as the rescue ship was on the opposite side of the Mohawk, its searchlight vividly outlined for us the situation we had just left. The Mohawk was well over on its starboard side and well down in the bow. Its rudder was in sight, as was a portion of the propeller, and then I saw three people jump from the stern and land with a splash in the zero water. Beyond this scene we could see another lifeboat full of people pulling off the starboard. We were only about a hundred yards away when she finally sank, the port side of her stern going down last.

Osterhout, Myers and Rockwell found themselves in less than congenial company as their lifeboat slowly made its way to the Algonquin.

Several waves were so large that they blocked out our view of the ship entirely. The spray from them froze immediately and was a sickening sight. One or two of the men in our boat were lying on the bottom and shouting orders to us, which made me mad, for they were no more eager to reach that ship than the rest of us pulling on the oars.

…it was then that I began to get seasick and realized also that my left ear was freezing.

.Roy’s partner had given up rowing because of the cold, and several men were sick around me, which did not help my stomach at all. Two other men near me were complaining of the cold and refusing to row which made Roy mad and he was giving them hell.

…as we got nearer to her, I gave up all interest in rowing and spent my time trying to keep my cold feet out of the water in the bottom of the boat, my left ear from freezing, and my dinner where it belonged. As we came up to the port side of the Algonquin, they threw us a line of heavy cable from their cargo opening. Being eager to get in to a more solid structure, I grabbed the rope and hung on. As our boat swung past the door, Iwas almost dragged overboard between the two boats, but two men grabbed on and we were pulled up to and into the ship.

On board the Algonquin, the young men tried to make themselves as comfortable as possible as the horrible realization that they were the only survivors from their party sank in.

About this time, Larry Rockwell and Roy Myers went by our stateroom door, headed towards the bow, and feeling in need of action I put on my shoes and followed them. They were tending to those who needed aid and were assisting everyone in general. As other lifeboats were picked up from time to time, we found plenty to keep us busy. After some time, with people settled in as much as they could be, we decided to go to Mrs. Maurice’s stateroom as she seemed to be the most congenial as well as the most cheerful person on board.both of the women were frightfully cold, and the doctor thought that Mrs. Maurice’s mother might be dead, but she came to slowly in a warm cabin.

I made a round of the staterooms to see if I might recognize anyone. As all the stateroom doors were left open, it was easy to see everyone and everything that went on. Near the stern on the starboard side I saw two young women, Mrs. Lord and Mrs. McKee, taking care of Mrs. Telfer and the four months old baby. Lone of the women was feeding the baby milk from a bottle and using the finger from a rubber glove for a nipple. In some staterooms people were groaning, while in others they seemed very calm and were trying to get some rest. But few were the people I recognized on that tour of inspection.

.Mrs. Maurice, in her quiet way, told us of her travels and did her best to keep our minds off the last few hours.

Going back to the stateroom, I took my old seat–a chair at the head of the bunks. Roy was still in the same place–lying on the upper bunk.

As for the three of us, we often spoke concerning the other members of our party. Mrs. Maurice tried to keep up our spirits, and a little hope was raised when word came that the Limon had picked up one lifeboat. But our hopes never rose too high because of our mental picture of our friends’ poor chance of escape.

Larry and Roy decided to get some sleep. Larry went off by himself, so Roy and I went to a stateroom, where he got into the lower berth and I got into the upper. Roy preferred to have the light left on; and it was better than the lonely darkness. After tossing around and trying to get comfortable, I gave up the idea and went back to join the group in Mrs. Maurice’s stateroom. It wasn’t until breakfast that I saw either of my companions again, as they were both able to get to sleep.

.I did not feel hungry myself, but went into the dining room, and there a great thrill awaited me, for at one of the tables, along with Mrs. Lord and Mrs. McKee and the elder Mrs. Telfer, sat the five year old Telfer boy, of whom I had seen nothing since his lifeboat went over the side into the water. I seated myself at a table nearby, with Roy and a middle aged foreign gentleman and his wife,. Breakfast, when it came, consisted of fried eggs, ham and coffee.

Long before we took on our pilot in new York harbor, life on board became very lively. People were walking about and the hum of voices could be heard in the cabins. It was much too cold to remain long on deck, but from time to time we did venture forth for a few moments. When the pilot came aboard, many of the Ward line investigators came with him. They took our names and desired to know where we planned to go when the ship docked. Those who wished could stay at the Hotel New Yorker at the company’s expense.

The nearer we got to our pier, the more eager people were to leave the ship. Roy, “Rock”.and I stood on the deck watching the tugs trying to maneuver us up the Hudson. The river was filled with floating ice, and the sides of the lounge and trails were covered with ice.just before we docked, the three of us returned to the stateroom and saw Mrs. Maurice for the last time.

As soon as we were permitted, we hurried down the gangplank and the long wooden landing to the waiting room. I saw a great crowd of people peering anxiously towards us. Then there were the flashes of flashlight cameras.the next thing I knew, two men had hold of me. One had his arm around my neck, the other his arm around my waist; a third man was drumming me with questions, and all three were insisting I should speak over the radio. Propelled by them I went up to the microphone, where already one of the survivors was talking. I was much relieved the next instant when a newspaper man, a friend of Mrs. Symmes, was able to get me away..we headed for the Williams Club. Rockwell had departed with his family and Roy Myers was staying with the Symmes family.

Karl Osterhout was well enough to attend the funeral of Professor Cleland, at Williamstown, the week after the sinking. He had been recovered, along with Lloyd Crowfoot, Julius Palmer and William Symmes, in the cluster of 33 bodies found drifting near the wreck site on the morning after the disaster.

Palmer Grave

Of the three survivors, Osterhout died on April 3, 1992. Lawrence Rockwell died in 1975, Roy Huth Myers died in 1979.

I have never known such fear

I have never known such fear

Jim Kalafus and Mike Poirier

Two days after the disaster, portions of a statement issued by Williams President Tyler Dennett appeared in the press:

(Professor Cleland) was one of our oldest and most revered professors who by steady persistent effort built up a department of geology of which Williams College has been very proud.

Lloyd Crowfoot, Julius Palmer and William Symmes, all seniors, had made honorable places for themselves on the Williams College campus. The reports of their work, year by year, reveal faithful efforts, sometimes in the face of considerable hardships. Under Professor Cleland’s instruction they had been touched with his enthusiasm for geology and went to their fate as young men might, with hope in their faces and the respect and love of very many friends.

The Telfer family of whom the Pillsbury sisters and Karl Osterhout spoke, were en route to Mexico where John Telfer, formerly the assistant Chief Engineer of Mexican National Railways, would be serving as the British Vice Consul at Orizaba. Traveling with him were his mother, Mrs Alice Telfer, his wife,Catehrine Butler Telfer and his two sons Ian Crichton, 5, and Clive, an infant. The stately elderMrs. Telfer, 67, was brought to the New Yorker Hotel in Manhattan, in shock, while her grandchildren were taken to the Broad Street Hospital where they were photographed several times and were the subject of many articles. John Telfer’s body was identified by the New York agent of the Mexican National Railway on January 26 1935, while that of his wife was tentatively identified by Alice Telfer who recognized scraps of the clothing the body wore.

The Peabodys, of whom the Pillsbury sisters and Osterhout wrote, were Julian and Celestine Hitchcock Peabody, of Westbury, Long Island, New York. Julian Peabody, 53, was an architect of some reknown who had designed many North Shore public buildings, including Westbury High School. He was best known, however, for the extensive renovations to the Hotel Astor at Times Square in New York City that he designed and executed. Celestine, 39, was a North Shore socialite known for her skills as a rider, and was the sister of polo player Thomas “Tommy” Hitchcock. Their estate, Pond Hollow Farm was said to have been one of the finest on Long Island. Married since 1913, and the parents of two children, the socially prominent couple were en route to Guatemala for a winter vacation: Julian carried his art supplies with him and planned to pass his time in Central America painting. They were not trapped in the Sun Parlor and carried down with the ship- both bodies were recovered- and it is likely that the couple were waiting for the initial rush towards the lifeboats to die down and simply ran out of time.

Julian Peabody

“The last time I saw or spoke to my parents probably was the week-end before they embarked on the Mohawk.The effect of the sinking and the loss of my parents was catastrophic… Julian L. Peabody jr, Nov 15, 2005

Although some details of their accounts do not dovetail perfectly, it is likely that music executive James Gibson was in the same boat as the Pillsbury sisters:

When the boat was lowered it hung stationary at the water’s edge. One of the sailors had an axe and he chopped at the ropes, cutting all but one when the axe slipped out of his hands into the water.

There we were, with one rope holding fast to the bow of the sinking ship. It was so cold we could hardly move. We bobbed there for about 15 minutes, then the bow began to go under water and it looked as if we’d be dragged down. One of the men in the boat had a pen knife. A sailor took it and was able to hack the rope apart. We drifted away and we were not clear more than five minutes when the Mohawk sank.

I don’t see how the collision could have happened. Someone was to blame; you could see for miles around.

28 year old, James Howie of Brooklyn gave this account:

I was sitting at the bar with a couple of other fellows when there was a sudden jar and the boat appeared to come to a stop. I ran out on deck. I saw the bow of the Talisman pushed far in our side. Then the freighter backed away slowly.

I walked amidships and asked a member of the crew if there was any serious damage. He said it didn’t look so good, and that he heard two men were killed in the crash and four others had been washed out of their bunks through the hole made by the freighter.

Everything was amazingly quiet. The members of the crew were orderly. They guided us to our boat stations and they lowered the lifeboats without the least sign of disorder.

There was a year old baby in our boat. There were also about twenty other people, most of them women.

When we had rowed half a mile from the Mohawk I heard a terrific blast. Apparently a boiler had burst. I saw the smoke stack falling. The ship was then at an angle to the sea and it gave me a sick feeling. I didn’t have the heart to see it go down and turned my head away.

Engelbertis “Eddie” DeWaard, leader of the Mohawk orchestra, survived to give this brief, but good , first person account:

There was no panic. Everyone was just running around, shouting for friends, trying to get life preservers on, and warm clothes. The crew ordered everyone to the boats.

First the Mohawk tipped far over to starboard. There was snow piled up under the lifeboats. Some boats on the port side couldn’t be lowered at all, the Mohawk had listed so bad.

Then the ship straightened up again, ten minutes after the crash, maybe. They got lifeboats into the water. Then it tilted the other way. It began to sink by the head. It plunged straight down 80 minutes after it was hit. There were still may people on it.

We got our lifeboat over all right, but I saw one that hung down from the davits. The seas were rolling high. We picked up one boy but couldn’t reach any others. I couldn’t find my drummer, Anton Woeffel. I think he died.

Alfonso Garcia 27, Mexican businessman told this vivid story of the Mohawk tragedy:

I was playing cards in a cabin with three other men I never saw before. I don’t know their names or whether they were saved. After the crash I dropped my ‘near flush’ and sprawled on top of the cards. The boys forgot about the money on the floor as they left the cabin.

Stewards ran about yelling “Put on your lifebelts” I headed for the passenger dining room where about fifty men and women gathered. They were calm at first as they were told to await further instructions.

It was a darn long wait for the signal to go upstairs. When we didn’t receive instructions, somebody started a rush for the stairs and most of them ran up. I was surprised that no one was stepped on, for it was a pretty panicky group and I don’t like to think about some of those men running.

There was plenty of trouble getting our lifeboat off because of the ice. Twenty persons, including an eight year old child got in our lifeboat. There were only two members of the crew in our boat. I helped row until I no longer could work my hands and arms, which got cold. I then took an electric torch from a member of the crew

For Mr. and Mrs. Patrick Fitzgerald of Waterbury, Connecticut, the Mohawk disaster brought a tragic solution to a family mystery. Their son Christopher had left home in 1926, and the family had neither seen nor heard from him since. A 32 year old crewman aboard the Mohawk named Christopher Fitzgerald died in the sinking. He had given a Waterbury address when he signed aboard the ship, and investigation showed him to have been the missing man.

“I want a hairdresser and I want her quick” said Evelyn Levine of New York City and Havana from the Hotel New Yorker where she had been taken after her rescue. Mrs. Levine had spent her last $40 to purchase passage to Cuba, where she was to meet her husband, and had boarded the Mohawk only 5 minutes before the gangplanks were hauled in.

Well, I’m back in New York again, and I’m broke.

When the ship sailed I didn’t immediately go to my cabin, as I wanted to walk around and get a feel for the ship being a voyager of many trips. Well, anyway, I was just hanging around the purser’s office when there was the “boom” of the crash. I knew then that the ship was doomed and nothing could save her.

I’ll tell you what it sounded like- that crash was like two houses smashing together-it knocked me and other passengers down. We then gathered in the purser’s square. I heard someone say “there’s water on the decks” then someone said “Shush! Don’t let anyone hear you say that even if it is true!” Right then I got a little hysterical as I had no life preserver. So I turned to a member of the crew who had one on him and said to him “Will you give me your lifebelt” it was crazy to say such a thing, but now what do you think he did? Why, he jerked it off and handed it to me without a word, while another sailor helped me into it.

The crew took orders well, the officers got great discipline from them and all the passengers kept their heads as far as I could see. I left in the second lifeboat, as the searchlight from the Algonquin kept playing on us. Once we seemed to have lost the Algonquin but we picked her up again. When we got near the Algonquin someone from the liner yelled “row around to the other side” so we did.

It was pitiful for some of the older women and men. The old men just stared at the sea while the old women tried not to groan in that awful cold with water from the sea falling on them.

Gee, I’d love to get to Cuba and see that husband of mine. How’ll I do it?

Mrs. Charles Hone of Eastchester, New York, and her daughter, Mrs. Stewart Maurice (1894-1992) of Chappaqua, New York met with a local reporter in Mary Hone’s Eton Hall Apartment on Garth Road and gave a refreshingly candid account of the disaster. In the upper class manner of the day, they refused to divulge any personal information or discuss anything other than their having survived the disaster; even their destination remained ‘off limits’ for publication. This was the same Mrs. Ellen Maurice who so charmed the surviving Williams College boys.

My daughter and I had retired early. We were tired. We had been in our berths amidships on B Deck. I cant say how long we were in our cabin. I think I was asleep although I heard the crash and felt the jar from the impact.

The jar was very slight, not enough to throw us from our berths, and the noise wasn’t very loud. After a few seconds hesitation we got up. Looking out the porthole we could see the Talisman just a few feet away. We were on the side that was struck.

We realized the Mohawk had been hit but had no idea it was serious although something seemed to make both of us realize at once that we had better don our lifebelts. We threw on a few clothes and put on the belts. There seemed to be no undue excitement. Only a minute or two had passed and we were just completing the adjustments on the lifebelts when our steward knocked on our door. He was calm and in a voice that showed no alarm or trace of excitement asked if we were awake and told us to put on our lifebelts and go on deck. We had no trouble reaching the deck although by the time we got there the Mohawk was listing badly.

Sailors and officers on the decks directed us to our lifeboat. No one, passengers or crew, appeared excited. Strangely the vessel’s listing seemed to stop and the ship straightened up just after we had gotten in the lifeboat. I think the water rushing into the hold probably straightened up the Mohawk momentarily. It was fortunate because it permitted the safe lowering of the lifeboat.

There was a bitter cold wind blowing and the sea seemed to be running very high. At least I thought it was high, although anyone on the deck of a liner wouldn’t call it a ‘high sea.’ It certainly seemed rough in that lifeboat. The sailors in our boat got it away from the side of the ship in a very short time.

In our boat there were about eleven women, eight men and six or seven members of the crew. The crew did have some trouble keeping the craft moving. The wind that was blowing and the cold water that splashed in a spray into the little boat made maneuvering it rather difficult. I thought we’d freeze out there. We wore very little clothing.

We hadn’t gone very far. It seemed as though not much more than twenty minutes or a half hour had elapsed since the Mohawk was struck when we saw her begin to sink. The bow went down and within a few minutes she disappeared. It didn’t seem possible. The whole thing happened so quickly.

I estimate that the lifeboat was in the open sea for ninety minutes before we were picked up by the Algonquin. As soon as we were aboard the Algonquin we were all taken care of. My hands and ears seemed frozen and found I had hurt my leg in some manner. My injuries are nothing serious. My daughter escaped with no injuries whatsoever as far as I know.

The only dry clothing available aboard the Algonquin was a pair of sailor’s pajamas. Besides these I was given a heavy warm blanket. I want to say that the crew of our ship certainly did all that could be expected of them. They can’t be praised too highly. On board the Algonquin we were also treated fine.

Mrs. Jeanette Brucker, of Mansfield Ohio, boarded the Mohawk with her sister, Miss Alice Williams, and their mutual friend Miss Dorothy Dann (1895-1980). The three, later described as “leading figures in Mansfield society” were trading the cold of an Ohio January for 24 days in Vera Cruz, Mexico. Mansfield, at the time, had a spirited newspaper, the News-Journal, and from its pages the pre-tragedy lives of the three Mohawk women are easy to document; other than Mary Pillsbury Lord, the Williams College party and the Peabodys, more can be learned about Mrs. Brucker and the Misses Williams and Dann than any of the other passengers. For instance:

| Four generations of a Mansfield family will be patron members of the Red Cross for the remainder of their lives. They are Mrs. Jeanette P. Hodges, 157 Park Avenue West; her daughter, Mrs. Charles Williams 24 Stewart Avenue; her grand daughter, Mrs. David Brucker, and her great grand daughter Jane Brucker, of 157 Park Avenue West. Besides these four, there are five other members of Mrs. Hodges family who are patron members of the Red Cross.

Miss Alice Williams, a grand daughter, is also on the list. (November 1933) |

On the night of the collision, Mrs. Brucker and the Misses Williams and Dann set out for the lifeboats together; however, Miss Dann returned to her cabin to get a blanket and while

returning was physically propelled by a crewman into a boat on the promenade deck. Mrs. Brucker and Miss Williams had continued upward to the boat deck. Aboard the Mohawk, as aboard the Titanic, confusion over where to board the boats cost lives: some boats were filled on the boat deck and then lowered past the passengers waiting properly at their boarding stations one deck below, while in other cases boats were lowered to and loaded from the Promenade Deck leaving people who mistakenly went to the Boat Deck stranded. That is what happened to Mrs. Brucker and Miss Williams. From her lowering lifeboat, Miss Dann heard Mrs. Brucker calling “Dorothy Dann- where are you?” from the boat deck. She called back to them, but never knew whether or not they heard. Both women sank with the ship and were lost. In a letter to her family Miss Dann wrote:

returning was physically propelled by a crewman into a boat on the promenade deck. Mrs. Brucker and Miss Williams had continued upward to the boat deck. Aboard the Mohawk, as aboard the Titanic, confusion over where to board the boats cost lives: some boats were filled on the boat deck and then lowered past the passengers waiting properly at their boarding stations one deck below, while in other cases boats were lowered to and loaded from the Promenade Deck leaving people who mistakenly went to the Boat Deck stranded. That is what happened to Mrs. Brucker and Miss Williams. From her lowering lifeboat, Miss Dann heard Mrs. Brucker calling “Dorothy Dann- where are you?” from the boat deck. She called back to them, but never knew whether or not they heard. Both women sank with the ship and were lost. In a letter to her family Miss Dann wrote:

I had no place to sit, so I stood up for two hours wedged in among a lot of frantic people. The boat was leaking, the water was up to my ankles. My hat blew off, I lost my pocketbook containing my valuables.

Our boat crashed into the big boat – the Mohawk. The ropes on our boat became entangled with the end of the Mohawk that was going down, and we all thought we’d be drawn down by the suction. The steward cut one rope with a hatchet and then lost it. A man in the boat gave him a pen knife and the other rope was cut loose. And then we were free. There were four or five men in the water near us crying to be saved. We dragged in two of them but the others went down. One of the men had on only his underwear- I gave him my blanket. Then the cold was terrible and I have never known such fear.

We watched the Mohawk over on her side, going down rapidly. I looked once or twice and then turned my head away. It was too terrible.

Mrs. Brucker was found the following day floating close to the wreck site, while Alice Williams was swept many miles up the coast and not found for several days. Both women were returned to Mansfield and buried at Mansfield Cemetery. Unfortunately, the story does not end there:

OHIOAN’S BODY FOUND HANGING IN APARTMENTMansfield Man Takes Own Life In Phoenix Arizona.Grieved For WifeMan Despaired Since Wife’s Death In Mohawk Ship Disaster.David F. Brucker, 44, Mansfield, was found dead in his apartment in Phoenix yesterday. Police said the body was found hanging from a steam pipe in the kitchen. Officers said Brucker, a former ice cream manufacturer, had been despondent since the death of his wife in the Mohawk disaster last January. An inquest was held to be unnecessary. “There is no doubt about the identification” Judge Brucker told the Associated Press when informed of the death. He said his son, who visited here about a month ago, went to Arizona for his health. Brucker had worked as an ice cream and coffee salesman, and is survived by a daughter, Jane, 20, who resides in Mansfield. (August 17, 1935) |

The Mohawk came to rest in 70 feet of water, six miles off of Manasquan, New Jersey. She lay almost within sight of the Morro Castle’s hulk, and airplanes conducting aerial searches for Mohawk victims flew in close to the earlier wreck and photographed it; winter storms had moved her further down the beach in the direction of the Convention Hall, giving the resulting photos an unfamiliar look. A pair of lifeboats that self launched from the sunken boat deck drifted forlornly above the Mohawk, still tethered to their davits, while the bow of a third boat attached only by the stern, pointed towards the sky over the wreck. Most of the 47 victims were found drifting in a cluster close to the wreck site, but some- such as Alice Williams- had been taken by the current and drifted up the coast. A handful were never found.

The Mohawk, despite the social prominence of some of her survivors and victims, her high death toll, the proximity of the wreck to New York City, and some disturbing questions regarding safety and stability raised by the collision, vanished rapidly from both the press and public consciousness. Unfortunately for her posterity, the disaster occurred during the final week of the Hauptman trial and, unlike, the Morro Castle,. there was limited column space available to cover the story; even on day one, the Mohawk tragedy shared a split headline with Hauptman on the cover of most newspapers.

One senses, reading through the U.S. Government report on the disaster, issued in 1937, that the press missed a great story. The report frustrates the contemporary researcher, for it is a detailed series of recommendations pertaining to both the Morro Castle and Mohawk affairs, and makes references to other reports from which it was culled, without quoting directly from them. Of particular interest, at one point the report describes “four compartment’ “three compartment” “two compartment” and “one compartment” ships, as determined by the amount of damage they could sustain and survive in an accident, and then goes on to say, in a passing reference:

The Mohawk, under the laws in effect when she was built, was not even a one compartment ship. While it is true that had the Mohawk been subdivided in accordance with the convention requirements, and had she been stable when in the damaged condition she would probably not have foundered.

The members of the Committee on Commerce, for whom the final report was intended, would have heard the testimony and read the accounts which support that statement, and therefore no further expansion on the theme was needed, however, to a historian it raises and does not answer a number of nagging questions. A search is currently underway for the full testimony and supplemental reports that went into the creation of the final paper, and more will be said on this most interesting of tangents as information becomes available.

The Morro Castle was pulled free from the beach at Asbury Park, at last, on March 14, 1935. She was towed first to Gravesend Bay in New York, and then on March 29th to Baltimore, Maryland where her remains were scrapped at the Union Shipbuilding Company.

Scrapping the Morro Castle

On June 28th, she caught fire once again when bilge oil was ignited by a scrapper’s blowtorch. At about the same time, the Mohawk, resting in water so shallow that on sunny days she was visible from the air, was dynamited and wire dragged as a hazard to navigation. The job proved to be more difficult than anticipated:

SUNKEN WARD LINER RESISTS DYNAMITEThough she sank easily, the Ward liner Mohawk is stoutly resisting the efforts of engineers to blow her to bits on the ocean floor. The Mohawk went down after a collision with the freighter Talisman last January with the loss of 46 lives. She lies in 80 feet of water, a menace to navigation in the busy steamer lanes. Efforts to break the hull with charges of dynamite were begun last week by a salvage crew. The first explosion shook but failed to break the hull. Another was touched off yesterday, but engineers indicated that at least three more charges would be needed. (August 6, 1935) |

Her bow survived the blasts, lying on its side, but the rest of the liner was reduced to a low-relief jumble of wreckage strewn across the ocean floor. Since the advent of SCUBA , she has become one of the most popular dive sites on the East coast due to her closeness to shore, shallow depth, and seemingly endless supply of artifacts.