Morro Castle, Mohawk and the End of the Ward Line : Part 5

Jim Kalafus concludes his account of the Morro Castle disaster and how it led to the rapid demise of the Ward Line.

The end of the Line

Oriente at Havana

The Oriente had her first brush with notoriety in 1935, but compared to those that plagued her lost sister it was relatively minor:

CUBANS TO DEPORT 17 AMERICANSU.S. Party of Probers Held in Guarded Camp Pending Speedy ReturnSeventeen men and women who came for the United States to investigate conditions on behalf of liberal and radical organizations were held under machine gun guard at an immigration center today pending the departure of the liner Oriente. They were led by Clifford Odets, brilliant young radical dramatist, whose three Broadway plays-still running- were the sensation of the theatrical season just ended. The delegation arrived aboard the Oriente last night. Two hundred policemen guarded the Ward line dock while detectives boarded the liner and herded them into the writing room. After questioning they were taken to the Tiscornia Immigration Center and held until the Oriente departed this afternoon. A minute examination was made of the delegates’ baggage and many documents were confiscated. Thirty port policemen armed with sub-machine guns guarded them. It was understood that two American Federal Agents had watched the delegation aboard the Oriente. Police said the delegation was detained ashore because the Oriente’s captain was reluctant to accept responsibility for them. It was understood that passengers has complained that two Negroes who accompanied the delegation danced with white women delegates. Manning Johnson, a Negro, was handled roughly by a detective aboard the Oriente because he refused to answer questions. The heavy guard at the dock was intended to frustrate a welcome by a Cuban Communist Committee Police announced that they had arrested twenty-four members of the welcoming committee including eight women. |

The Ward Line did not long survive the triple disasters of 1934/5 and the bad publicity of 1933. Despite the nine years of service she gave to the Clyde Mallory Line, the Mohawk’s six hours of life as a Ward liner — and she was always referred to as a sunken Ward liner in articles — were enough to drive the final nail into the corporate name’s coffin. The funnel markings aboard the Oriente and other ships of the line were painted out, anecdotally as a sign of “mourning” for the lost vessels, and the name Ward Line dropped from all advertising in favor of the company’s official title Cuba Mail Line.

The Oriente was given a “glamorous” makeover in the late 1930s, and emerged with all-outside cabins, and new funnel markings similar to those of Clyde-Mallory, consisting of a star between two white bands across the center third of the funnel. Fortune Magazine, in its September 1937 special maritime issue, ran what proved to be the longest and most detailed review of either the Morro Castle or Oriente. Fortune, at that time, catered to an extremely rarified audience, and the review – at times – has an irritatingly condescending tone to present day readers. Excerpted here:

SIX DAYS AT SEA.On A Good “Average’ Cruise to Havana. The Four Handsome Airedales Wanted Girls; the Girls Wanted Husbands; the Tourists Wanted a Hot Time Ashore; The Cuban Boys Wanted Transportation. The Cubans Got What They Wanted. Force of habit awakened elderly Mr. And Mrs. B. early and they were strolling t he long decks hand in hand a half-hour before the dining saloon opened at eight. Two heavy women in new house dresses helped each other up the stairs, their lungs laboring. They were Mrs. C. and her feeble sister. They and the B’s nodded and smiled and said what a lovely morning it was and moved on in opposite directions. Mr. B. replaced his alpaca cap and told his gentle, pretty, wife how fine the sea air was and what an appetite it gave a fellow. The sun stood bright on the clean, already warm decks, the blue water enlarged quietly without whitening and sang along the flanks of the ship like seltzer. Miss Cox appeared with her aunt Miss Box a frugal and sweet smiling spinster. Miss Box wore a simple print and a shining black straw garlanded with cloth flowers; Miss Cox was in severely informal new sports attire. Like most of the other young women, low salaried office workers upon whom the self sufficiency, the independence of city work and city living had narrowed their inestimable pressures of loneliness and of spiritual fear, she set a greater value of anticipation upon this cruise than she could dare tell herself. For this short leisure among new faces she had invested heavily in costume, in fear, in hope; and like her colleagues she searched among the men as for steamer smoke from an uncharted atoll. Small and very lonesome in a great space of glassed in deck, an aging Jew in a light flannel suit gazed sorrowfully at the Atlantic Ocean. A blond young man who resembled an Airedale sufficiently intelligent to count to ten, dance fox trots and graduate from a gentleman’s university came briskly into the dining room in sharp pressed slacks and a navy blue sports shirt, read the sigh, dashed away and soon reappeared plus a checkered coat and a plaid tie. The dining saloon opened. Among big white tables glistening with institutional silverware all the white-coated stewards stood in sunlight with nothing yet to do. They were polite but by no means obsequious; like the room stewards and the rank and file of the crew they had a good stiff draught of the C.I.O. The headwaiter, a prim Arthur Treacher type conveyed his guests to their tables with the gestures of an Eton-trained sand hill crane in flight. His snobbishness rather flattered a number of the passengers. Mr. And Mrs. B. studied them pretentious menu with admiration and ordered a whale of a breakfast. They may charge you aplenty, but they certainly do give you your money’s worth. Mr. L. a bearish Jew, and his wife, the hard glassy sort of blonde who should even sleep in jodhpurs tinkered at their fruit and exchanged monosyllables as if they were forced bargains. The Airedale pricked up his ears as two girls came in and as quickly drooped them worried his Rice Krispies, hoping that to the two girls already seated he had appeared to establish no relationship with the newcomers who were not at all his meat. Mr. and Mrs. L. in the manner of the average happily married couple, brightened immediately and genuinely as friends entered. The cool china noise and the chattering thickened in the cheerful room while, with the casualness of concealed excitement, studiously dressed and sharply anticipatory, singly and by twos and threes the shining breakfast faces assembled, looking each other over. The appraisals of clothes, of class, of race of temperament, and of opposite sexes met and crossed and flickered in a texture of glances as swift and keen as the leaping closures of electric arcs, and as essential irrelevant to mercy. These people had come aboard in New York late the evening before, and this was their first real glimpse of each other. All told, there were about one hundred thirty two of them aboard. Perhaps twenty of them, mostly Cubans, were using the ship for the normal purpose of getting where they were going, namely, Havana. The others were creatures of a different order. They were representatives of the lower to middle brackets of American urban middle class and they were on a cruise. Forty of them would stop a week in Havana; they were on a thirteen- day cruise. Sixty- eight of them would spend only eighteen hours in that city. They were on the six- day cruise. Most of them were from the cities of the Eastern seaboard; many were from the New York City area. Roughly one in three of them was married, one in three was Jewish, one in three was middle aged. Most of the middle aged and married were aboard for a rest: most of the others were aboard for one degree or another of a hell of a big time. The unattached women and girls, who were aboard partly for a goodtime and partly for the more serious, not to say desperate, purpose of finding a husband, outnumbered the unattached men about four to one going down, and about six to one coming back. There were few children. It wasn’t a very expensive outing they were taking: most of them spent between $85 and $110 for passage but $70 was enough to cover every expense except tips for six days. There were bar expenses; and plenty of the passengers, particularly the younger ones, had invested pretty heavily in new clothes they could fee self-assured in; for most of them had never been on a cruise before and had rather glamorous ideas of what it would be like. Few of them could swing this expense lightly, and plenty of them knew they should never have afforded it at all. But they were of that vast race whose freedom falls in summer and is short. Leisure, being no part of their natural lives, was precious to them; and they were aboard this ship because they were convinced that this was going to be as pleasurable a way of spending that leisure as they could afford or imagine. What they made of it, of course, and what they failed to make, they made in a beautifully logical image of themselves: of their lifelong environment, of their social and economic class, of their mothers, of their civilization. And that includes their strongest and most sorrowful trait: their talent for self deceit. Already as their eyes darted and reflexed above the grapefruit and the coffee they were beginning to find out a little about all of that. The ship these passengers were aboard was the turbo-electric liner Oriente, the property of the New York and Cuba Mail Steamship Company, which is more tersely and less gently referred to as the Ward Line. The T.E.L. Oriente is fashioned in the image of her clientele: a sound, young, pleasant and somehow invincibly comic vessel, the seagoing analogy to a second-string summer resort, a low priced sedan or the newest and best hotel in a provincial city. She can accommodate some 400 passengers, and frequently enough carries half that many. She makes fifty voyages a year, New York-Havana-New York, carrying freight, mail and passengers, of whom a strong preponderance are cruising. CONGENIAL SHIPMATES JOIN YOU IN “PUTTING THE SHIP THROUGH HER PACES” .the cruise brochure says, adding “And you’ll find the Oriente lives up to the most exacting demands.” It must be suggested that the truth of such qualitatives as delightful, splendid, delicious is highly relative. In other words, a lot depends on the point of view. In that case, the following could quite as reasonably be said: people don’t become so very well acquainted: they are too shy, and afraid of getting stuck. Few of the passengers have a royal good time because they have never had a chance to learn how. The splendid orchestra is hard worked corn fed summer hotel. The delicious meals are indeed what a cruise passenger might order in a fine restaurant ashore. Even effervescence is relative; some people find enough in a bottle of club soda opened night before last. The passengers spent a good deal of time on their own resources. Those resources showed their inadequacy in proportion to the eagerness of the passengers reaction to any program of fun that was arranged for them. The eagerness in turn was in proportion to the juvenility of the program. Party hats and noise makers were sure fire; the moment of loudest and most general gayety during all six days was the close of a game of musical chairs: the most steadily popular collective diversion was the most solidly an irretrievably lower bourgeois: Bingo. There was a moderate amount of drinking but little drunkenness and almost no conviviality. Flirtation seldom reached either high temperature or seriousness. Much of the dancing was constrained; there was no cutting in. After the first three days the average passenger was bored with himself and whomever he knew and sank into depression. And yet that is not the whole truth. The same passenger was possessed of illusions to match those set up in the brochure, and their protection was ensured by the genius of his class and country for self deception. So amphibious was he between illusion and reality, and so swiftly capable of mending his own wounds that on the mot essentially literal plane those illusions were quite as true as the realities. Up on the sports deck in bright sun a gay plump woman in white shied rubber rings at a numbered board and chattered with her somber companion. She admired Noel Coward almost fatuously and sat at the captain’s table. She was the godsend of the week to the captain, a Dickensian built Swede who enjoyed gallantry and wit, and whom even the stewards liked. A slender Jew made a few listless passes art shuffleboard and then settled down to obstacle putting. The Airedale and a duplicate appeared in naughty trunks, laid towels aside from their pretty shoulders, oiled themselves, and after a brief warm up began to play deck tennis furiously before the gradually assembling girls. Some of the girls wore brand new sports clothes, others brand new slacks or beach combinations. Some of them traveled in teams, most of the others teamed up as quickly as they could. They strolled against the wind, they stood at the white rail with the wind in their waved hair, they swung their new shoes from primly crossed knees, they layback with shaded eyes, their crisp white skirts tucked beneath them in the flippant air, they somewhat shyly lay their slacks back from their pale thighs, they lay supine, skull eyed in goggles; their cruel vermilion nails caught the sunlight. They examined each other quietly but sharply, and from behind dark white rimmed lenses affected to read drugstore fiction and watched those beautiful bouncing blond boys’ bodies and indulged in long thoughts of youth. The Airedales were fast and skillful, and explosive with such Anglo-Saxonisms as Sorry, Tough, Nice Work, Too Bad, Nice Going. Later they were joined by a couple of other bipeds who had the same somehow suspect unselfconsciousness about their torsos, and the exclamations of good sportsmanship came to resemble an endless string of firecrackers set off under a dishpan and the innocent childlike abandon of exhibitionism acquired almost Polynesian Proportions in everything except perhaps sincerity and results. To come to the quick of the ulcer, it is generously estimated that the sexual adventures of the entire cruise did not exceed two dozen in number and most nearly approached their crises not in staterooms but aboveboard: that in no case was the farthest north more extreme than a rumpling hand or teeth industriously forced open; that in 70% of these cases the gentleman felt it obligatory to fake or even to feel true love, and the lady murmured “Please” or “Please don’t” or “I like you very much but I don’t feel That Way about you” or all three: and that the man, in every case, took it bravely, sincerely adapted the attitude of Big Brother and went to his bunk tired but happy. There were a number of shifts of table at lunch as new acquaintances got together. It was standard, sterile, turgid summer hotel type of food, turkey, duck, the sort of stuffing that tastes like kitchen soap, fancy U.S. salads and so on, and served with a pomp and circumstance that would have sufficed for the body and blood of Brillat-Savarin. The average passenger behaved a little as if this were his regular Thursday evening at the Tour’d Argent and staggered upstairs to digest at the horse racing. |

In 1938 and 1939 the final Cuba Mail Line vessels were introduced, the Mexico and the Monterey. Neither were new-builds; the former having previously been the Colombian Line’s Colombia, and the latter having been the Porto Rico Line’s Puerto Rico, both built in 1932. They were smaller and considerably less luxurious than the Oriente, but menus and programs from the liners’ two year careers show that they offered similar quality food and entertainment. In keeping with former Ward Line tradition, there were three instances of drug smuggling discovered aboard the Mexico during the spring and summer of 1939. On May 9, 1939 452 grams of marijuana were seized by customs officials; on July 11, 1939 4 grams were discovered, while on August 22, 1 kilogram, 327 grams was found. In all three cases ownership was not determined.

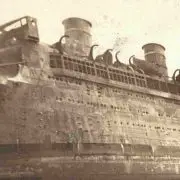

Oriente remained in service between NYC and Cuba, and NYC-Cuba-Mexico through 1941, without event. Always the less notorious of the sisters, she seldom made the papers, other the than on the “departures page” and the occasional society column blurb. In June 1941, with war clouds gathering, she was requisitioned by the Army and renamed Thomas H. Barry after conversion to troop transport. As in her civilian life, her career as a transport was consistent and unspectacular although two months after the war’s end, she rammed and sank the trawler Medford southeast of Cape Cod. She was not returned to the Cuba Mail Line, and alternated between lay up and transport duty until November 1957 when, like her ill- fated sister ship, she was broken up at Baltimore, Maryland. Her older consorts, Siboney and Orizaba were not returned to Cuba Mail, either. Siboney remained in Army service through 1957, at which point she was broken up in Baltimore, while Orizaba – the probable rum runner of the 1920s- was sold to the Brazilian Navy and renamed Duque de Caxias. 18 lives were lost aboard her in a 1946 fire, but after a rebuild she survived until 1963. Yucatan-ex Havana, was scrapped in 1948, while the final Ward liners Mexico and Monterey were sold to Turkish maritime interests, postwar, and survived until 1966 and 1967 respectively. AGWI, the Ward line’s parent company survived until 1953, while the Ward Line name lived on beyond that point as the Ward-Garcia line of freight ships.

Dedicated to Tim, Peter and Zoomer, three of a kind, and to Jake, Andrew, Steve, John and Serge who got me through my own Mohawk period.

Thanks to Marty Oppenheim who went the extra mile researching for me! His help in bringing the stories of the Queens and Long Island passengers to life, and his solving the “mystery” of Mrs. Ford Reinekins were invaluable and appreciated. Thanks are extended as well to Bart Malone for his ongoing help and for talking me into SCUBA lessons so I can visit the Mohawk in 2007. Additional thanks to Kyle Johnstone and Harald Advokaat. Special thanks also to Mike Poirier for 5 years worth of excellent contributions, to Bob McDonnell, and to Anthony Cunningham for the use of his Dolly McTigue interview.

Deserving of special mention is Ms. Linda Hall of Williams College Archives and Special Collections, for allowing Mike and I access to, and use of, the Osterhout account and the Yucatan Expedition photos.

Thanks to Hildo Thiel for compiling the various Mohawk lists into one master list.

Special thanks to Brandon and Linda McKinney whose editorial input will, no doubt, be as appreciated by readers as it was by me!

Particularly effusive thanks are extended to Mike Poirier, who stepped in after this manuscript was allegedly finished and offered so many interesting ‘leads’ that the whole thing groaned to life again and expanded by dozens of additional pages.