Passport to Perdition

How an expired passport could have prevented an untimely death on the Lusitania.

AN EXPIRED passport could have prevented the untimely expiry of a life on the Lusitania.

But instead its holder, Thomas J. Silva, moved heaven and earth to get replacement documents in order to sail on the fatal voyage that left New York on May 1, 1915. In doing so, he obtained his own death warrant.

The demise of plain Tom Silva, a salt-of-the-earth son of the south, is uncommonly well documented. There is his last letter home – on Lusitania stationery – the desperate telegrams after the sinking, a communication of regret from Cunard, clips of news coverage, tributes of sympathy, and a gripping letter from a survivor about his last minutes alive.

It all elevates him from the mass of the 1,198 who died into a well-drawn character of nobility and strength. Fleshing out one individual may offer its own tribute to the rest, those who embody the “thousand natural shocks that flesh is heir to.”

IT WAS a consummation devoutly to be wished. The 1909 marriage of Thomas James Silva and Ethel Dekle had long been hoped for by both families. Not that the respective scions kept their kinfolk waiting, for they wed when each was just twenty years old.

He was from Atlanta, she from Thomasville – both Georgians; and both belonged to what remained of a faded antebellum aristocracy, one that held on to good breeding and good manners. The new partners were exemplars of both.

The couple’s first child, bouncing son Frank Robertson (Bobby) Silva, arrived when they were both 22. Two years later came a daughter, Bettina. It was 1913.

Left to right: Bettina Silva, Ethel Silva (nee Dekle), and Bobby Silva

A blissful family life seemed to hold the promise of perfect happiness forever. The Great European War, when it came a year later, was but a puff of smoke on the far horizon.

Yet in time the strife came to trouble Thomas Silva, an Anglophile who was also a Teutonophile. “He went often to England and Germany, buying and selling cotton,” said daughter Bettina Silva Callaway in November 2006. With friends in both countries, it is easy to imagine his loyalties torn.

In the ten years of his business career Silva had spent “two or three seasons” in Bremen, Germany’s second largest port, the Savannah Morning News later noted. Bremen’s twin city, Bremerhaven, was now a major base of her proud new fleet of Unterseebooten.

Still, no-one dreamt of submarines that early in the war. To Americans, it was a conflict drawn in barb-wire lines across the European landmass. When discussion turned to the sea, it was about the prospects of the British battleships drawing out those of Imperial Germany to the high seas where they might be destroyed and the war speedily ended.

The dawning of 1915 changed such thinking. The U-boats had begun sinking British shipping by the hundred tons, and neutral vessels were not immune from fog-of-war attack. In February, the German Government warned that the waters around the British Isles would now be considered a war zone, and all shipping flying a combatant flag – meaning the White Ensign – were liable to be sunk.

This announcement of a ‘paper blockade’ attracted much scorn from the British press. But it was a source of concern to Transatlantic travellers, all the more as companies like Cunard aggressively asserted the safety of the passage.

When 26-year-old Thomas Silva boarded the RMS Lusitania in May 1915, he was something of a hostage to “business as usual” in more ways than one. A cotton-broker, working on the Cotton Exchange in Savannah, he was ultimately bound for Bremen to negotiate new contracts.

The first time he had been to Bremen, to clients called Robertson, he travelled alone. On another occasion, in peacetime, he had brought his wife and new baby (Bobby). Old man Robertson was so impressed with little Bobby’s composed manner that he allowed him to sit at the table for meals, a privilege not extended to his own grandson.

The third time Silva was due to go to Bremen he travelled alone, not just because there was a war on, but because Ethel had her hands full with two babies at home. Besides, he had his passport to sort out – while she had announced her intention to return to her parents in Thomasville with the little ones during his absence.

Thomas Silva’s letter, composed on the ship, speaks for itself –

|

Dearest Eff, After a long hard journey I arrived in New York on the 29th of April. The trip was certainly a long one and I was glad indeed when it was over. The first thing that I endeavoured to do was to try to get my passport. |

SIX days later, there was no waiting convoy of destroyers in the danger zone. But there was the lurking U-20, commanded by Kapitänleutnant Walther Schwieger, and he saw to it that Thomas Silva would not be getting back early, or at all.

The day after the sinking, a telegram to Silva’s workplace from Cunard confirmed:

May 8, 1915

Mr Silva was booked saloon passage. Name not yet reported from abroad.

Cunard S. S. Co.

It was followed almost immediately by a wire from the New York friend with whom Silva had dined before leaving on the Lusitania, the man who called on some contacts in Cunard to secure him the best berth at a minimum price. It was also sent to Tom’s employers, based in another state:

Parrish & Co., Temple, Texas.

Cannot get any information Silva. Cunard lists do not show him among survivors. Will wire again tomorrow.Steinhauser

Tom Silva had begun his career in the cotton business with the Espy Cotton Company of Savannah in 1905. He was then associated with W. W. Espy in Thomasville after leaving Savannah, and had “severed his connection with that firm to accept a position with E. T. Robertson & Son in Bremen.

“Recently he was connected with Parrish & Company of Temple, Texas. He had just closed a most successful season when he sailed for Europe on May 1 on business for the firm, expecting to return early in July,” it was reported.

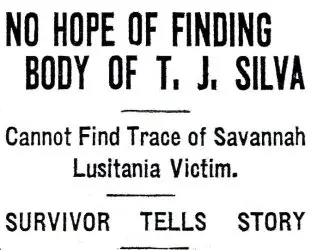

“When news reached his relatives that he was not among he saved, they used every means in their power to ascertain his fate and learn whether the body was recovered.”

The Temple Daily Telegram reported on Sunday morning, May 9, 1915:

“No definite word comes to the stricken wife and the business and personal friends of T. J. Silva of Temple, who is among the “unrecovered” of the Lusitania horror.

“There are of course chances that other survivors were picked up at sea by boats headed for distant ports, or there may have been survivors landed at points along the coast and not reported. The faint hope will be cherished until complete information is obtained.”

Mrs Ethel Silva was reported to be “hoping against hope” that a message would come. “She is tenderly cared for by friends and neighbours.”

The newspaper’s headline that day read: “SHIP’S DEATH LIST IS 1,198. Temple Man Is Believed Among Lost.” Claimed by both Texas and Georgia newspapers, Silva was one of 120 Americans to perish.

The next day, Monday May 10, a Western Union telegram arrived at the office of Parrish & Co, where many workers were learning for the first time of the involvement of one of their colleagues in the cataclysm.

From New York dealer W. H. Hubbard, it read:

|

“SIX PM. HAVE JUST HAD CUNARD PEOPLE ON PHONE. AM GRIEVED. HAVE REPORT MR SILVA STILL ON MISSING LIST. FEAR PRACTICALLY NO HOPE, BUT WILL KEEP IN TOUCH ADVISING ANY NEWS. YOU HAVE OUR DEEPEST SYMPATHY.” – View telegram |

A more personal telegram to Mrs Silva arrived from Tampa, Florida, on May 11 –

|

“CLIFF LEFT THIS MORNING FOR YOU AND BABIES WILL ARRIVE THURSDAY. LOVE FROM ALL – BOB.” |

The fruitless hunt for news was taken to the very top, as the Texas newspaper reported in midweek (Thursday May 13), six days after the sinking:

INTEREST AROUSED

IN FATE OF SILVAInformation is sought concerning Temple man on ill-fated Lusitania

An appeal to Governor James E. Ferguson to do all in his power as chief executive of the state of Texas to interest Secretary of State William J. Bryan in demanding all information possible as to the fate of Thomas J. Silva, an employee of the cotton firm of Parrish & Co, who was on board the ill-fated passenger steamer Lusitania when it went down last Friday, has been made by Mayor J. B. Watters of Temple.

The mayor is doing all in his power to get all the information possible as to the fate of Mr Silva and the establishing of his identity at the improvised morgues along the coast of Ireland, in case he is dead.

The following telegram was sent Governor Ferguson by Mayor Watters yesterday:“Temple, Texas, May 12, 1915.

Hon. James E. Ferguson, Governor, Austin, Texas.

Thomas J. Silva, an employee of the cotton firm Parrish & Co, Temple, took saloon passage Lusitania.

All telegrams and cablegrams from his firm, friends and family have brought no information as to his safety or loss. Cablegrams to Cunard Steamship company, Liverpool and Queenstown, are unanswered.

Mr Silva’s wife, children and friends are deeply grieved and I appeal to you as our chief executive to confer with Secretary William J. Bryan and ask him to demand all information possible be furnished without delay. Answer.J. B. Watters

Mayor of Temple.”

The political efforts show the desperation of the family, including Tom’s sisters Margaret and Mary, his brother Frank, and his mother, a widow, who had remarried to become Mrs W. H. Teasdale.

Thomas and Frank Silva

The telegram also hints at the huge workload that had just fallen on Queenstown, the site of three major morgues improvised in response to the tragedy, and nerve centre for the recovery efforts all along the south coast of Ireland.

By now, unbeknownst to his kinfolk, a physical description of passenger Thomas Silva had been received in the Town of the Dead, as it was quickly dubbed –

Thomas Silva: Tattooed Elk’s head on left arm and Greek band on right arm. Five feet eight inches high, age twenty-six.

This was a very useful guide. The Elk motif derived from Silva’s membership of the Thomasville lodge of the Benevolent and Protective Order of Elks, the local chapter since defunct.

The Greek band apparently signified his involvement in athletics, having been a member of YMCA teams in Savannah, where he “took an active part in the gymnasium” and was “well liked by all those who knew him.”

But no such body had been recovered. Or ever would be.

Strange to say, among the unidentified to this day is body 146, an American whose remains contained an unfinished letter of ship’s stationery, beginning: ‘Dear Ted – We hit New York at 7.30 in the morning, and after seeing to our luggage we made our way to Bronx Park to see some friends of mine…’

With better communication and more publicity, this body, consigned to Mass Grave B in Queentown’s Old Church cemetery, might easily have been identified.

As the days went by, hope faded for Thomas Silva. The family hopes were finally all but dashed by a letter from Cunard:

|

PLEASE ADDRESS ALL COMMUNICATIONS TO THE COMPANY AND NOT TO INDIVIDUAL EMPLOYEES PASSENGER DEPARTMENT

Mrs. Thomas J. Silva, Dear Madam, In reply to yours of the 26th- inst. we beg to say that we greatly regret being unable to give you any information in reference to Mr Silva and can only state that up to the present time there has been no indication that any of the recovered remains were his. Of course you will appreciate that there was a very large number of persons on board the steamer and only a limited number of those survived, and likewise not a great many of the bodies have been recovered. Everything was done by the employment of a great many vessels to try and recover as many of the bodies as possible, but doubtless a very large number of passengers were drawn down with the steamer when she sank. and may not have come to the surface again. We enclose herewith a list of the saloon passengers as desired and we assure you that if at any time we receive any information that we believe would be of interest to you will only be too glad to promptly forward it. Permit us to extend to you our very sincere sympathy at your loss. Yours truly, The Cunard Steamship Co., Ltd |

Among the tributes to Tom Silva to arrive was this one, from T. T. Timayenis, Editor of the Eastern and Western Review, who had been asked to use his good offices in securing further information for the family:

|

Dear Mrs Silva: I have duly received your letter of May 13th. It is impossible for me to express in words how sorry I feel because of the untimely death of Tom. I learned to love him. He was a manly fellow, of noble character, and every inch of him a man. |

But it was not quite ‘impossible to add anything further.’ The family eventually tracked down a survivor who recalled Tom Silva clearly from the voyage. His name was Charles Thomas Jeffery, a saloon passenger and President of the Jeffery Motor Car Company of Kenosha, Wisconsin.

Ethel Silva, Charles Jeffery

The Silvas had been trying to find Mr Jeffery ever since an interviewer in Queenstown had questioned him in the immediate wake of the sinking. Quotations from that interview found their way into the New York World of May 10, 1915

Quickly clipped out and sent to the family by more than one person anxious to assist, the excerpt quoting Mr Jeffery ran:

”I was the only person saved from our table of five in the saloon. There was a splendid young fellow in our party named Silva, in the cotton business, coming over to Liverpool, who might surely have been expected to battle his way through, but I am afraid he was lost.”

This paragraph led to a continuous effort to locate Mr Jeffery after hope for Tom Silva’s safety had been abandoned. But it quickly turned into a dead end – because the New York World had mistakenly described him as president of the Bridgeport Motor Car Company of Bridgeport, Connecticut, instead of the Jeffery Motor Car Co. of Kenosha, Wis.

Eventually Jeffery was traced, and his reply to a letter is here recited in full:

CHARLES T. JEFFERY 6-28-15

Mrs Thomas J. Silva

Temple, TexasMy dear Mrs Silva:

It is with much regret, and with deepest sympathy, that I am writing to you now regarding what little I knew of your husband on the Lusitania.

I would have written you earlier but in London, when I made inquiry at the Cunard line, they were unable to give me your address and, as every week I intended to return to the States, left the matter until I could get on this side and learn in some way where I could communicate with you.

Mr Silva and I were at the same table in the dining room and, becoming acquainted, spent considerable time in the smoking room. Excepting those at our table, neither Mr Silva nor I became acquainted with many others, beyond a few young fellows whom we met in the smoking room.

I have seldom met a man of whom I became so fond in a short time as your husband. He was a clean, fine fellow and unusually likeable. I know that everyone who came across him must, as I do, feel deeply his loss.

On the morning of the disaster I did not get out of my stateroom until about twenty minutes past one and, going to the smoking room saw Mr Silva and two others sitting there and I joined them, but as the others soon went to lunch, Mr Silva and I sat alone when, noticing a slight list of the vessel and some vibration we went out of the smoking room to the veranda, which is really an open air end close to the smoking room.

From there we saw that the vessel had made a half circle. I remarked to your husband that the Captain must have seen something, referring to the possibility of a submarine. Then, seeing that the ship had resumed her former course, we returned to the smoking room where your husband and I sat on the couch talking.

While, at first, I had no idea of going to my lunch because I had had a late breakfast in my cabin, I concluded to go down and get something light, but Mr Silva said he was not hungry and he decided not to go. I went down alone and left him reading a book or magazine.

I returned to the smoking room in about half an hour and your husband was still there reading. I sat alongside of him and we were talking for probably ten minutes when we felt the shock and the bang of the torpedo hitting us.

We both ran out again to the veranda and, having noted by the direction of the sound that the torpedo must have hit us on the starboard side, went in that direction, but, as many others were coming out at the same time from the different companionways, on the same errand as we were to try and discover what the trouble was, he and I soon became separated in the crowd. As I was curious to see whether I could learn anything on the other side of the ship, I went around to the port side, but learned nothing and returned.

Probably you have read an account of my experiences, which were, however, that of many of the survivors, but I merely wanted to add to this that, when I arrived in Queenstown, I made enquiries at the hotels and went around among the survivors, but was unable to find your husband, nor did I find anyone who had seen him.

The next morning I went around to four different places where the bodies of those which had been found were taken, and I looked carefully over all of them, and could not find that of Mr Silva. I was told at the time that there were no more bodies being brought in and soon left for London.

In an interview with some reporter I mentioned that it seemed odd that I should be one of the survivors when men much better equipped physically to swim and stand the shock of the water were lost, and my only way of accounting for the loss of your husband is that he undoubtedly remained on the starboard side up to the last and then, when the ship rolled over, was unable to get away quickly enough and was carried down with it.

Your brother, Mr J. R. Dekle, has written me and I am today forwarding to him the signed statement which he wished to have.

If there is any information you would like to learn, that I can possibly give you, and that this letter does not cover, please do not hesitate to write me.

Again assuring you of my deepest sympathy,

I amVery sincerely yours

Charles T. Jeffery

In another letter, this time to Silva’s mother, Mrs W. H. Teasdale, Jeffery offered some further details in another telling of what he knew:

“I was with your son in the smoking room when the explosion took place. We went out together to look over the side at the spot where the ship was struck. The ship began to slowly list on the starboard side, and your son and I became separated in the crowd.

I did not see him afterward, and I am very sorry, Mrs Teasdale, that I am unable to give you any information as to how he was lost. Any opinion, of course, would be merely based on conjecture. The boat sank so rapidly the last two or three minutes and she rolled over on her side so quickly that those on the starboard side had almost no chance of being saved.

At Queenstown I visited the morgue and later examined all the photographs of those whose bodies were recovered, but your son was not among them.

Mr Silva’s personality was one that appealed to those who became acquainted with him on the ship. He was the type of man that men like. When I got to Queenstown and ran across Mr [James] Brooks of Bridgeport and later Mr [Allen] Barnes of Montreal (two of our ship acquaintances) almost their first questions were regarding your son.”

Further testimony to Silva’s nobility of character was contained in a letter received by his mother from his employer, Will Espy of Parrish & Company, in whose interest he had undertaken the voyage.

“We held Mr Silva’s business ability in high esteem. He was very popular with our firm and his friends here and in other towns, and we have received letters of sympathy from those whom he had met in a business way in the cotton business and who had grown to love him for his prompt and just dealings, his friendly personality and his ever-present good nature.

We were always glad when he came in off the road as he made life more pleasant in the office and his sunny disposition and constant smile will ever cause him to be remembered by those of us who loved him.

The writer has known him from youth to early manhood and has always entertained for him the sincerest feeling of friendship, affection and esteem. He was a splendid boy, clean of mind and body, upright and of strong character and ability, and it is sad indeed to think that when these fine qualities were beginning to achieve results, that when his future was beginning to ripen into a rosy and fair outlook, that his young life should be nipped in the bud by such a startling and terrible catastrophe.”

Ethel Dekle Silva never remarried. She taught piano lessons to children and adults and died in 1977, just before her 88th birthday.

Tom Silva’s son Bobby grew up to become a civil engineer. He graduated magna cum laude from Washington and Lee University in Lexington, Kentucky.

Bobby died suddenly in his seventies from a heart attack in the late 1980s. He and his own son – named Tom in memory of the grandfather – had just returned from a golf game.

“Mama talked a great deal about it (the Lusitania disaster) when we were kids,” Bettina says.

She is glad her father’s story is being recorded as the 100th anniversary approaches, as if the preservation of memory were itself a passport to the past.