Peggy on a Skin Boat

Memories of a banana boat deckhand

At the age of fifteen back in 1953, I Joined the Red Funnel Steamship Co. serving on three of their paddle steamers, the Princess Elizabeth, Bournemouth Queen and Lord Elgin and then finally their flagship, the twin screw Balmoral. All of these vessels either did round the island cruises in the summer months or carried cars and cargo’s to the Isle of Wight throughout the year. We very often did tender jobs to the big ocean liners anchoring off of the Isle of Wight in the Cowes Roads in those days which included such ships as, the Ile de France, Nieuw Amsterdam, Flandres, Statendam and many other foreign ships that used tendering as a cheaper option to berthing in Southampton docks. As a deck boy, I was expected to clean up vomit, run errands when ashore, wash and dry all the dishes, scrub out messrooms and cabins, make tea every hour of the 16 hour day and get stuck into some real seamanship when I had the time. After a year of serving on these little ships, I couldn’t wait to sign on in the Merchant Navy and go “deep sea” as it was known and perhaps have an easier life. However, I was in for a few surprises when I finally signed on in January 1954 on an Elders and Fyffe’s banana boat, the M. V. Nicoya, an ex German prize vessel of 2,300 gross reg. tonnage with a passenger carrying capacity of six. It is said by seamen that you never forget your first trip to sea and in my case I was certainly no exception.

The Princess Elizabeth

Courtesy of John Megoran

Banana boats were always known as “Skin Boats” by seamen in those days and Southampton was a popular port for these vessels and regularly used by Elders and Fyffes Line, using this as their home port. A ship’s “Peggy” was the Deck Boy or general “dogs body” for the want of a better word and as this ship had only signed on one “Peggy”, clearly I was in for a bit of a “work up.” The use of the term “Peggy” comes from sailing ship days and may well mean to “peg away” or to work consistently of which I would go along with that!

The Lord Elgin

Courtesy of John Megoran

On the first day out at sea, the First Mate, a swarthy looking man with a hard face that had more craters than the moon’s surface, called me out onto the wing of the bridge away from my brass cleaning duties in the wheelhouse. Joining him there, he turned to me and said in a strong North Country accent, “When you signed on lad, one of your conditions of employment stated that you would have every Saturday afternoon and all day Sunday off”. Never really understanding what I had signed, I looked up at him in utter disbelief, my heart Jumping a bit as I thought that perhaps this voyage wouldn’t be so bad after all. Sunbathing up on deck in the tropics every weekend would be just what the “doctor ordered” I thought and I couldn’t wait to cash in on some of that when the weather got warmer.

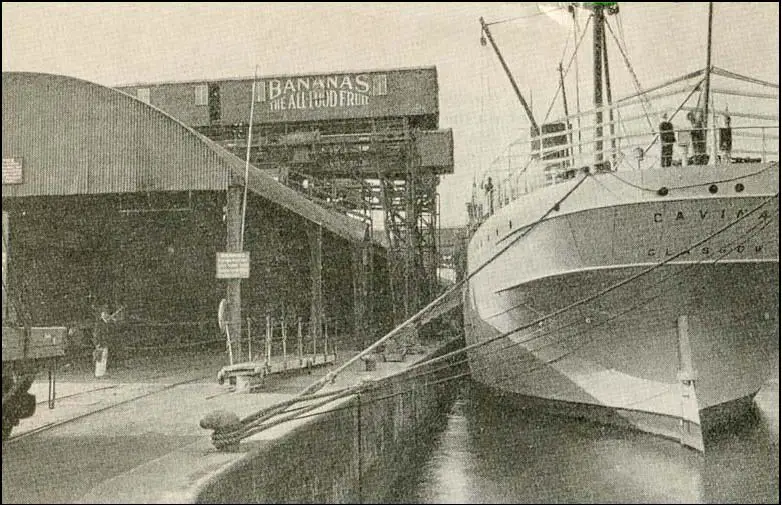

Elders and Fyffes’ Cavina discharges its cargo at Bristol’s Avonmouth dock.

Looking down at me as though I had just crawled out of a bit of cheese, the Mate went on almost in exasperation, “What the hell you’re going to do onboard here with a day off, God only knows!” Changing his mood somewhat, he then went on almost matter of factly, “Usually, the “Peggy” has an arrangement with the crew and continues to get their grub and keeps the messrooms clean and tidy on those days.”

My face must have dropped on hearing this as I began to realise that my time off on this voyage had just been “nipped in the bud’.

Following the Mate back into the wheelhouse, he picked up a pair of binoculars to observe a ship on the horizon before speaking to me again. Lowering the glasses and turning back towards me, he reminded me of a school teacher, fast losing patience with a pupil by saying, “Do you understand what I’m saying lad! They’ll have a ‘whip round’ and collect a few bob’ for you at the end of the trip!” Noticing that his patience was now wearing a bit thin, I made a hasty retreat muttering “yes sir. I’ll ask them sir”

When I got below, I put it to the crew and they agreed that I should continue working for them throughout my weekends and as one of them put it. “You’ll be OK ‘Pegs’, we’ll look after you.” Yeah, right!

During that first day out at sea I began to learn very quickly what my work load was and between being sent to various parts of the ship on false errands purely for the crews entertainment, I began to wonder what I was going to do for sleep. Apart from cleaning out all the accommodation daily I would have to go on deck in the afternoons and work in the lifeboats and clean never ending paintwork. There was the captains inspection three times a week and all the tables, chairs and lockers were of unvarnished wood and showed every finger print and mark. These would have to be scrubbed until they were virtually white and as there wasn’t the range of detergents then as there is today, I was advised by one of the “old sea dogs” on board to use neat lime juice to help clean this woodwork and then wash it all off with soapy water.

Lime juice came in demijohns so there was plenty of it around and could be found on most British Merchantmen which dates back to the times when scurvy was a problem on long voyages. In it’s neat and concentrated state, the juice is like acid and requires a great deal of sugar to make it drinkable, The “old sea dog” that gave me the tip on the cleaning properties of lime Juice, also advised me on how to clear a blocked lavatory. Having a problem one morning with flushing away one of the toilets, he rolled up his sleeve and plunged his arm down around the ‘S’ bend. With his arm completely submerged and his head almost inside the pan, he turned his head slightly to one side and said to me in a broad West Country accent, “A bit o’shit won’t hurt ya lad” He was right of course. As long as it was his arm down there and not mine, I didn’t see any problem!

With all the showers, cabins and toilets to clean, there were also meals to be collected from the galley amidships three times a day, all dished up on plates serving twelve men aft and four PO’s amidships. This meant struggling along half the ship’s length with plates strung out on each arm in order to put the food on the table although they did allow me to use a tureen for the soup. One can imagine the many trips to and from the galley with mostly three course meals and a salad with each main meal of the day.

During the first part of the voyage with heavy seas in the Bay of Biscay, I did my best in trying to keep steady whilst trying to walk along the heaving deck during one particular mealtime. With three plates of food strung out along each arm, progress was slow with first, a couple of steps forward and then, three steps backward and then a little stagger sideways and then another attempt to move forward. With one leg in the air, poised to take another step, the ship buried it’s head into another huge wave and I lost my balance. I had misjudged the motion and found myself spread eagled on deck covered in gravy, meat and three veg along with dinner plates wheeling around in all directions. Returning to the galley to load up once more, the cook wasn’t a happy man sweating profusely and yelling at me to watch my step next time or “the bloody lot of you can starve!”

It was well known that the chief cook was a bad tempered individual, a bit of a hard case coupled with an extremely short fuse and I was used on the occasion, to relay the crews complaints to him about the food. On arrival at the galley doorway, the cook with arms like Hercules and hands like shovels would sometimes point a ladle at me and say, “Don’t say a word or I’ll fit this over your bloody head!” End of complaint !

The bosun, a Liverpudlian, was short and stocky with several scars showing through the hair on his scalp, blackheads in abundance, teeth that appeared to be spattered with tea leaves and a nose that had been reset a few times. However, he was despite his appearance, one of the biggest practical jokers onboard and a likeable bloke who taught me a great deal of seamanship. Noticing after a few days out at sea how unhappy I was looking, he set my mind at rest by saying, “You’re just a lad amongst a ship load of men. You’ve got nothing in common with them and the best way to come to terms with it, is to work hard, do as you’re told and become a man yourself !” Words of wisdom without a doubt.

On one occasion, the bosun told me to go and ask the cook about what kind of creation he had in store for us for dinner that day. On arriving at the galley door I noticed the cook had perspiration dripping off of his chin, was very red faced and looked extremely fearsome as he stirred various pots on the stove. Standing well back at a safe distance I repeated the same words as the bosun had used and with that, I thought the man would explode. Turning towards me I thought he was going to hurl the ladle at me as he stormed, “Tell your bloody lot and the bosun that you’ve got monkey shit and hailstones followed by Chinese wedding cake now piss off.” Fleeing the galley like a fart in a blizzard, I found the bosun up on deck and asked him what the cook meant.

The bosun burst out laughing saying, “He means curry and rice followed by rice pudding lad!” He then went on, “Don’t let that miserable bastard in the galley worry you son. It’s the heat in the galley that makes ‘em like that!”

After the ship had broken down with engine trouble a few times on our voyage to West Africa, we finally anchored just off of Port Victoria and discharged a bit of general cargo along with our only two passengers. My first impressions were the pungent smell of tropical vegetation, the lack of lights at night along the shore line and flying fish skimming across the top of the water from time to time towards our ship, attracted by the deck lights. Having completed our discharge, we then weighed anchor and proceeded up a jungle river to a tiny village-come shanty town named Tiko, which was our banana loading station. To reach there we slowly made our way up a muddy river, thick with mangroves on each side, accompanied by several dug out canoes until the Nicoya reached a bend in the river.

Slowing down to almost stopping, she continued straight ahead until gently nudging her bow into the soft spongy river bank causing foliage and branches to hang over the fo’csle head. With her rudder hard over and her one screw going slow ahead, she slowly brought her stem around until it was facing upstream. Once well positioned, she then went slow astern, slipping back away from the river bank and now with her bow facing down stream, she gently came alongside stern first to the wooden jetty and moored up in readiness for her cargo of around 100,000 stems of bananas to be loaded by hand.

Loading the bananas

During our stay of 3 days, I found it remarkable how this wooden pier seemed to stand up to the little banana train bringing load after load of stems of bananas from the plantation to the ships side for unloading. I also noticed a great deal of poverty here with the local loading gangs forever hanging around the galley for any little tidbits on offer. After the meals I would scrape all the leftovers into their tin cans and containers and watch some of them squat on the deck and eat with their hands whilst others would take these offerings home for their families. I had one local native that offered to wash and dry up for me and once he had completed his chores, I gave him a huge tin of ham, a loaf of bread and a bottle of tomato ketchup and you would have thought that he had won the lotto! It was however, sad to see such poverty and one can only hope today that their lives have improved greatly since that time.

We set sail for home, fully loaded and this time with no passengers on the return trip. After breaking down again around half a dozen times with the engineers cursing German engines, we finally limped into Garston docks in Liverpool almost three weeks later. As a result of continuing engine trouble throughout the voyage, a great deal of our cargo of bananas had turned to mush and was a total loss commercially.

My total pay off for almost five weeks at sea came to the princely sum of 12 pounds sterling and on arrival at Lime Street Station, the rest of those travelling back to Southampton, wanted to know how much had been collected for me for all of my weekend work. I looked at them blankly as we sat in the railway carriage before saying, “I never received anything” One of them laughed and said, “Come on ‘Pegs.’ How much did you get? We won’t get you to buy us all a beer.” Again I replied that no one had given me a penny except for my pay off money and as it was a collection, I wasn’t going to go around asking for it.

They began to look at each other realising that I was telling the truth and knew that the Lamp Trimmer had carried out the collection and then told everyone onboard that he had paid me. I was led to believe that everyone onboard had put a pound in the “kitty” for me which would have more than doubled my take home pay. The stark realisation that the Lamp Trimmer had ripped me off caused all those men in that railway carriage to vent their anger announcing that if ever they caught up with the rotten bastard again, they would swing for him. On arrival in Southampton, those ship mates, unknown to me, had another collection for me during the journey and thrust a hand full of notes in my hand as we left the train. I suppose one can say that I had certainly learned a few valuable lessons on my first trip “deep sea” and I would soon be ready for my next voyage, which turned out to be of 16 months duration, tramping around the Far East. But that’s another story.

The above article is an excerpt from David Haisman’s autobiography, “Raised On Titanic”. Copies may be purchased from the author.

Picture Credits* Princess Elizabeth: Courtesy of John Megoran (Paddle Steamer Kingswear Castle) Cavina at Avonouth Dock and Loading the Bananas: from Fruit Carrying Ships in Clarence Winchester ed. (1937) Shipping Wonders of the World. Volume 3.

* Note these illustrations are not from the book by David Haisman.

Excellent writing, great story