Solid flame from bow to stern

AN EARLIER MOHAWK DISASTER

On January 2, 1925, Clyde Line’s original Mohawk was destroyed by fire at the height of a once-in-a-decade storm off the New Jersey coast . The crew battled overwhelming odds to contain the fire long enough for the ship to enter sheltered waters, and succeeded: she was scuttled in 40 feet of water inside of the Delaware Breakwater after her passengers and crew were safely evacuated.

This dramatic, and charming, account was written by Margaret Mattingly, one of the stewardesses. It details one of the most amazing victories at sea ever won along the East Coast of the US.

The Mohawk was a lucky ship. She never has any mishaps and always made good time. All the Clyde Line crews liked to sail on her, and she was lucky to the last.

Just think of her burning in the water in a storm and every single one getting off safely! I surely did hate to leave her and think I’d never sail her again.

The sea began to toss us terribly as soon as we got past Sandy Hook. The wind was blowing right into our teeth. It was cold and raining and sleeting and nobody could think of anything but the storm. By evening hardly a passenger was able to be up.

They didn’t care much whether she burned or sank or kept afloat. They were too sick. If they had been feeling better they might have been a panic.

The blaze was discovered less than 12 hours after leaving New York. It was in the hold directly under stateroom J.

It was just after midnight. I slipped on my kimono in a hurry and went down the cabin knocking on all the doors and telling the passengers to get up. Then I went back and gave the women smelling salts and helped get them into their clothes. Most of them just groaned a little more and began grabbing their things.

We led the passengers to the forward Social Hall on the upper deck away from the fire. I didn’t see any crying and didn’t hear any of them praying out loud. One man played the piano a while and a doctor helped me and the other stewardess, Mrs. Gladys Stanton, take care of the sick. Mostly they just sat around or stretched out on the floor. It was cold, but smoke drifted in so we had to open a window every now and then. The stewards made coffee in the pantry and passed it around several times.

We just waited and waited. Captain Staples ran the engines as long as he could. Flames drove the stokers from the furnace room and he cast anchor.

Daylight certainly did look good. It was just about the worst winter weather you ever saw, with the sea pitching us two or three different ways at once. But we saw the Coast Guard cutter Kickapoo, and a tug, and a Merchants and Miners Liner and a freighter all there to help us.

The Kickapoo came in first, and all the women were put aboard her. I was the last woman to leave. The Mohawk then was listed to port at a steep angle, and the decks were slick as glass with ice. But somehow everyone got into the cutter without falling. It was terribly crowed there and most of us had to stand up.

Then when we landed at Lewes Delaware it was raining and we had to walk through the mud to the train. There wasn’t a dry stitch of clothing in the crowd.

On the train going up to Wilmington one of the stewards who was in the last boat load taken off told me the Mohawk made a grand sight at the last when she was a solid flame from bow to stern.

The destruction of the Mohawk stands in stark contrast to the similar situation that arose aboard the Morro Castle nearly nine years later. The crew functioned efficiently; the fire was kept at bay long enough to effect a rescue, and none on board panicked as survival options seemingly ran out .

Mohawk Final Voyage Passenger and Crew List

Compiled by Hildo Thiel with annotations by Jim Kalafus and Mike Poirier.

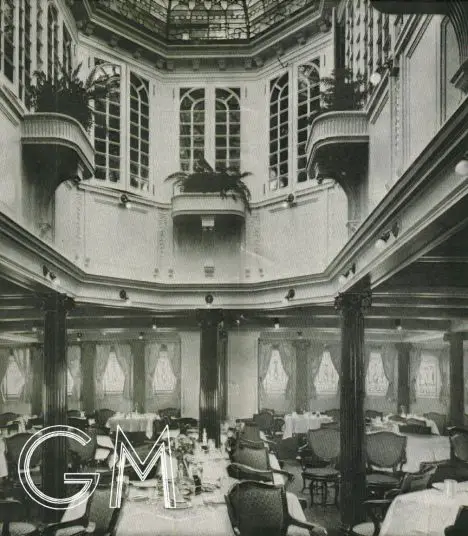

Mohawk (1908 Dining Room

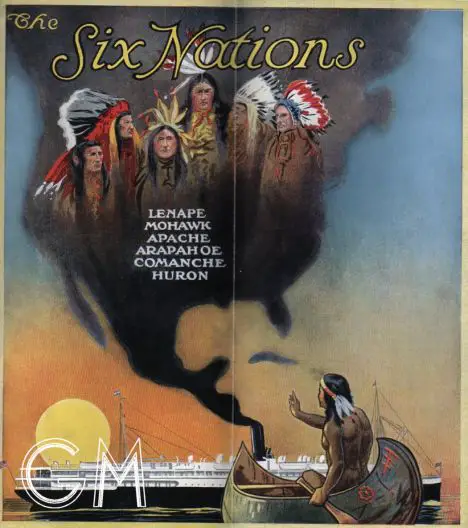

Mohawk Brochure c.1915