Swallowed in 14 Minutes

It took just 14 minutes for the St. Lawrence River to swallow the Canadian Pacific’s RMS Empress of Ireland in the pre-dawn of May 29, 1914. The disaster claimed 1,012 lives. More passengers, but less crew, perished in this tragedy than in the infamous Titanic sinking of 1912, and the catastrophe ranks as Canada’s worst maritime disaster.

The Empress’s sinking is one of a triumvirate of ocean liner disasters between 1912 and 1915 that took over 3,700 souls. The other two ships were the Titanic and Lusitania, and the stories of their losses are well known. What follows is the largely forgotten history of the sinking of the Empress of Ireland.

The Empress of Ireland

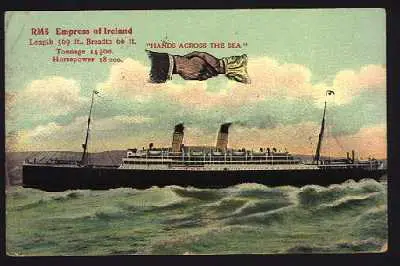

The Empress of Ireland, pride of the Canadian Pacific white empress fleet, was designed by Francis Elgar and built at the Fairfield Shipbuilding and Engineering Co. yards in Govan, Scotland (near Glasgow), and launched on the Clyde on January 27, 1906.

The Empress of Ireland, pride of the Canadian Pacific white empress fleet, was designed by Francis Elgar and built at the Fairfield Shipbuilding and Engineering Co. yards in Govan, Scotland (near Glasgow), and launched on the Clyde on January 27, 1906.

The liner was built to increase trade on the lucrative sea lanes between England and Canada, offering six-day voyages across the Atlantic. It sailed between Liverpool and Quebec City when the St. Lawrence was open for navigation, or from Saint John, New Brunswick in the winter months.

The Empress and its sister, the Empress of Britain, were twin-screw ships of 14,000 tons with a designed speed of 20 knots. Each had four complete steel decks. They were 549 feet long with a beam of 66 feet. The Empresses could accommodate1,550 passengers with 300 in first class, 450 in second class, and the remaining 800 in third class and steerage. Home port was Liverpool, and ships’ officers were British. Each vessel cost £375,000 to construct.

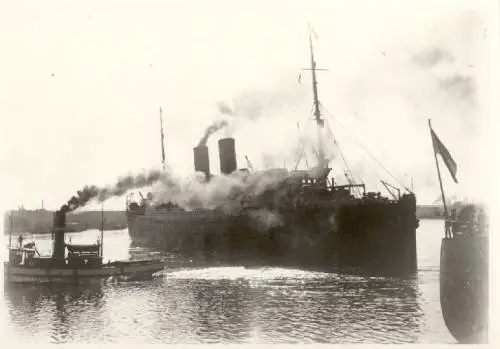

The Empress of Ireland entering port, from an original glass negative.

(Courtesy of Gavin Murphy, Canada)

The Empress of Ireland was a monument to Edwardian splendour. The first class accommodations included a library stocked with 650 volumes, a café, a music room, and a smoking room. The dining room featured leather upholstery, handmade woodwork, sculpted ceilings, cut-glass fixtures, and an atrium that went up two levels to the music room.

After the Titanic went down in 1912, ships of British registry were required to carry enough lifeboats for all on board. The Empress had 16 steel lifeboats, 20 Englehart collapsibles, and six other collapsible canvas boats. There were also 2,200 life jackets on board. The crew carried out regular lifeboat drills, and navigation, evacuation, and fire drills were mandatory.

The ship was divided into 11 sections by sealed walls known as bulkheads. When closed, twenty-four doors used for general ship purposes in the bulkheads made each section watertight. Nevertheless, the Empress could float with any two compartments flooded.

Captain for the Fateful Voyage

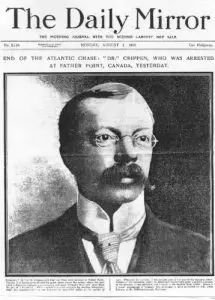

Taking command for the fateful voyage, his first as captain of the Empress when sailing from Quebec, was Henry George Kendall. Kendall was a 39 year-old rising star with Canadian Pacific, who first went to sea under sail. He had already made a name for himself in the arrest of Hawley Harvey Crippen in 1910 while master of the Montrose.

Crippen, a transplanted American doctor working in London, had killed his wife and dismembered her body. He was attempting to escape across the ocean to freedom in Canada with his young mistress disguised as his son. Kendall had the latest newspapers aboard (and a “keen eye”, as he said) and soon realized Crippen was a passenger on the Montrose. He notified the company’s Liverpool headquarters by wireless, who in turn advised New Scotland Yard.

The Yard dispatched Chief Inspector Walter Dew from England on a faster liner. When the Montrose stopped off Father Point, a tender was brought alongside. Up climbed Dew, who calmly walked over to Crippen and arrested him. Crippen allegedly put a curse on Kendall for his role in the arrest. “You will suffer for this treachery, sir,” he warned Kendall.

Crippen was returned to England to stand trial at Bow Street criminal court in London. After a five-day hearing, the jury found him guilty of murder in only 27 minutes. He was hanged on November 23, 1910.

Tragedy on the St. Lawrence

Heading down river on May 28, 1914 for its 96th trans-Atlantic crossing and the first of the summer season from Quebec, the Empress carried 1,477 passengers and crew, including 167 members of the Salvation Army, on their way to the third Salvation Army International Congress in London. The ship had cast off at 4:30 p.m. amid waving Union Jacks and shouts of good-bye. The Salvation Army band struck up the hymn “God Be With You Till We Meet Again.”

After exchanging the last mail bags at Rimouski and dropping the pilot, the Empress gathered up speed and headed for open water. On May 29 at 1:38 a.m., the lights of another ship were spotted. Kendall, who had just arrived on the bridge, took the binoculars and observed the Tyne-built Norwegian collier Storstad, a 6,000-ton vessel heading up river from Sydney, Nova Scotia. It was off the starboard bow about six miles away. The Empress altered course slightly, shortly before the Storstad disappeared into a fog bank.

Kendall ordered the Empress full astern and gave three blasts on its powerful whistle, indicating he was reversing. Then he stopped the ship and gave two more blasts, thus informing the oncoming vessel it was dead in the water.

At 1:55 a.m., Kendall was shocked to see the Storstad appearing out of the fog and heading straight for the Empress. He quickly ordered full speed ahead, but it was too late, the collier inflicted a mortal wound to the Empress between its two funnels. Kendall shouted through a megaphone for the Storstad to keep going ahead on its engines, in the faint hope it would serve as a giant plug. But the collier floated away into the night mists. Kendall struggled forward, unsuccessfully trying to beach the ship on the shores of the St. Lawrence two miles away near Father Point (12 miles east of Rimouski).

The Storstad had penetrated the Empress’s side, opening a 350 square-foot hole to the river. Within three minutes, the raging waters reached the dynamos and knocked out power, plunging frightened passengers, most of whom were asleep at the time of the collision, and crew into darkness. The ship took on a sharp list to starboard, and as water poured into the gaping wound at the rate of 60,000 gallons per second, Kendall ordered the lifeboats lowered and Marconi wireless operators Edward Bamford and Ronald Ferguson to send out an SOS. Passengers scrambled up on deck, many still in their night clothes, and some jumped into the frigid waters in a desperate attempt to save themselves. Many more remained trapped below.

The ship was in the grips of forces beyond its control. Only nine lifeboats could be launched before the Empress foundered. As it rolled over, Kendall was thrown from the bridge and eventually hauled into one of the lifeboats. By 2:10 a.m., less than a quarter hour from the time of collision, the Empress was gone.

The Storstad and two rescue ships from Rimouski picked up the survivors. When morning broke, the final count was 465 saved and 1,012 lost. Of 138 children embarked on the Empress, only four survived.

Lord Mersey’s Inquiry and the First World War

Just as he had done in 1912 after the Titanic sank, and was to do again in 1915, following the torpedoing of the Cunard liner Lusitania by a German submarine off southern Ireland with the loss of 1,198 lives, Lord Mersey presided over a Board of Trade inquiry into the loss of a British- registered passenger ship.

Convened in Quebec City on June 16, 1914, the inquiry found the Storstad at fault. A Norwegian inquiry, conducted at the Norwegian Consulate General in Montreal, ultimately exonerated the ship and its captain, Thomas Andersen. Andersen claimed the Empress caused the collision by turning northwest into the path of the collier. The two conclusions are irreconcilable.

With the outbreak of the First World War, the disaster quickly faded from memory. Kendall and Andersen served in the war, and both were torpedoed. Both men survived. But not the Storstad. It was torpedoed on March 8, 1917 and sank near the coast of Ireland. All hands were saved.

Kendall never returned to sea after the war, dying in England in 1965 at the age of 91. His obituary in The Times of London made no mention of the sinking of the Empress of Ireland.

On April 30, 1998, the remains of the Empress were declared a historic site by the Quebec provincial government. The shipwreck became the first underwater heritage site in Quebec, and also benefits from protection under Canada’s merchant marine legislation.

Why Forgotten?

The sinking of the Empress hit Canada hard and was the worst maritime disaster in Canadian history. Occurring just two years after the Titanic disaster, and a year before the loss of the Lusitania, it is essentially forgotten. Why?

The sinking of the Empress hit Canada hard and was the worst maritime disaster in Canadian history. Occurring just two years after the Titanic disaster, and a year before the loss of the Lusitania, it is essentially forgotten. Why?

The Empress disaster does not have the drama of the Titanic’s iceberg collision, nor is it the subject of countless films and books-or excessive hype. It carried ordinary people, unlike the Titanic’s millionaires and aristocrats. The Empress was not a leviathan, nor did it ply the popular route from New York to Southampton, England. There were enough lifeboats for all on board and it was not a maiden voyage. Nor did the Empress foundering have the political repercussions of the torpedoing of the Lusitania.

Three months after the Empress sank, the First World War broke out. The tragedy was quickly overtaken by death in Europe on an unfathomable scale. The loss from the Empress paled in companion with the wholesale slaughter wrought by modern warfare. The Empress simply passed into “forgotten” history.

Grace Hanagan Martyn, the last survivor of the sinking of the Empress of Ireland, died on May 15, 1995.

Photo: Memorial erected by the Canadian Pacific Railway on the south bank of the St. Lawrence River near Father Point (Courtesy of Gavin Murphy, Canada) .

Bibliography

Monographs

Rick Archbold and Robert Ballard, Lost Liners, (Madison Press: Toronto, 1997).

James Croall, Fourteen Minutes, (Michael Joseph: London, 1978).

Logan Marshall, The Tragic Story of the Empress of Ireland and Other Great Sea Disasters, (L.T. Myers: New York, 1914).

George Rasky, Great Canadian Disasters, (Longman Canada: Toronto, 1961).

Herbert Wood, Till We Meet Again, (Image Publishing: Toronto, 1982).

David Zeni, Forgotten Empress, (Goose Lane Editions: Fredericton, 1998).

Newspapers, Magazines and Journals

Atlantic Daily Bulletin (UK)

The Beaver, Canada’s History Magazine

Daily Mirror (London)

Montreal Gazette

The Times (London)

Titanic Commutator (USA)

Vancouver Sun

Weekend Magazine (Canada)

Other

Fourteen Minutes, CBC Radio “Disasters” series, 1985. Hosted by Laurier Lapierre. (Canada)

The Titanic, CBC Radio “Prime Time”, 1993. Hosted by Geoff Pevere. (Canada)

Journey to Oblivion, Merlin Films, 2000. Produced by Michel Prevost. (Canada)

Text and Images Copyright © 2000 Gavin Murphy