Lusitania : Passengers of Distinction

Stories of some notable Lusitania passengers.

Douglas Hertz

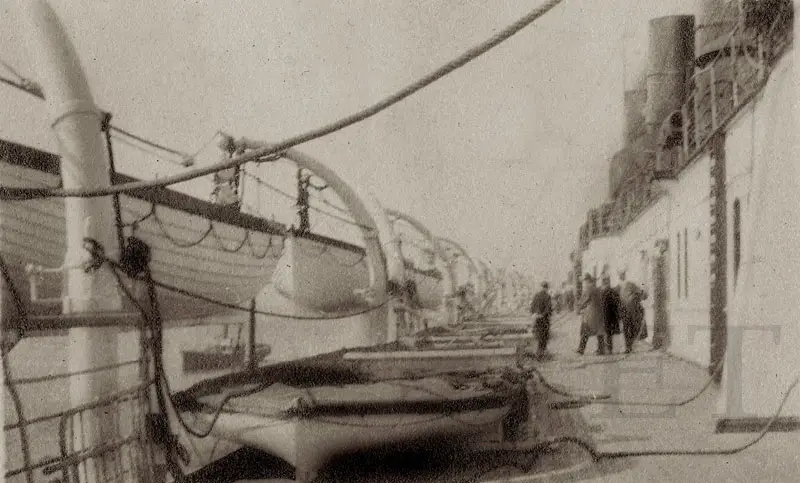

Photograph taken 24th April 1915 showing final configuration of the boat deck

Douglas Hertz, Lusitania survivor, may well have led the most colorful post-disaster lives of any of the passengers. Newspaper columnists loved to profile the likeable bon vivant, and Mr. Hertz was apparently not shy about supplying them with fresh copy.

Hertz was born in England in 1893. He would later tell reporters that he ran away to sea as a youth, and made two voyages, one as a cabin boy on a ship bound for Africa, and one as an oiler. He then settled down in a respectable position as a correspondence clerk at his father’s wholesale chemist and druggist business in London.

Douglas saved his money and, he would later tell reporters, traveled to the United States in 1910 seeking adventure. He aspired to Broadway success, but instead found himself as part of a touring group. He studied for the bar while living in St. Louis, Missouri, and after passing his exams in 1913, spent a year as a practicing attorney.

Hertz would claim that patriotism, and a desire to avenge the deaths of two of his brothers in the war, placed him aboard the Lusitania’s fatal voyage. He traveled in second class.

The moment that the explosion occurred, I got up from my seat and made for the deck. I had hardly taken a dozen steps when the second torpedo struck us with such force that I was knocked off my feet.

I made my way on deck as speedily as possible, and there I found everyone doing what they could to get the women and children into the boats, but unfortunately it soon became apparent that few if any of the ship’s boats could be successfully launched, as the vessel was listing so badly to starboard that the port boats hung right in over the decks and the starboard boats were swung out so far that it was nigh impossible to get into them.

I grabbed a half dozen belts from the first cabin I entered and returned to the deck to give them to women and children. Altogether I must have made six or seven trips below, bringing up lifebelts, before I realized how fast the boat had been sinking, but the last time I came up I had lifebelts in my hands and found nobody aboard to give them to. Then it dawned on me that I had but a few seconds in which to get clear, and for some reason that I have never been able to explain, I forgot to put a belt on myself but dropped all six on the deck and jumped overboard and set out to swim away from the ship.

I knew that she might sink at any moment and swam for dear life for the first minute or two without looking back. Then I turned on my back and witnessed the most tragic sight of my existence. The great vessel had gradually sunk by the bow until she was completely submerged to the fourth funnel, and she was now turning over, her starboard rail now being under water. Then, without warning, she lurched, hesitated a moment, turned over and was swallowed by the Atlantic.

I turned away from the terrible sight, and swam to the nearest piece of wreckage, climbed upon it, and sat there for eight hours until I was picked up by the patrol boat, Julia, of Queenstown.

Douglas Hertz was atop the same overturned lifeboat as Cyril Wallace and Belle Naish. Mrs. Naish sat beside Mr. Hertz, and would later testify that he signed his name to her shoe so that she would not forget it.

Douglas Hertz enlisted, and was granted a commission as second lieutenant in the South Lancashire regiment. He recounted that he saw action in the Dardenelles, and spent time training recruits. Suffering from “nerve paralysis,” he resigned from service at some point in 1916.

Details regarding the next portion of Hertz’s story are hazy, but during the summer of 1916, he returned to the United States aboard the New York, bringing with him his wife, Mollie, and infant daughter, Mary Madeleine. He also brought with him a motion picture, Fighting For Verdun, that he had produced.

Hertz passed his next few months promoting his film. A small article in the New York Times features Captain Douglas Grant Hertz informing an audience before on screening that he had personally seen the German submarine Bremen captured and brought to port in Wales prior to his departure for the United States. Reviews of Hertz’s film reveal it to have been a documentary, the principal flaw of which was a lack of either fighting footage or Verdun footage. Fatal omissions in a film titled Fighting For Verdun. The review in Variety quoted an audience member as telling Captain Hertz that she really enjoyed the orchestration that accompanied the screening.

Hertz then did film work at the various NYC area studios, appearing (unbilled) opposite Marguerite Clark, Pauline Frederick and Elsie Ferguson. He worked at Liberty Bond drives, as well. 1918 found him serving as a machinist’s helper at the Morse Dry Dock and Repair Company, in Brooklyn, NY. His Lusitania experiences, and autobiography up until that time, appeared in the company’s in house magazine, Dry Dock Dial, in October 1918.

Douglas Grant Hertz entered the United States in 1921, aboard the ship Panhandle State. He listed his occupation as publisher. The purpose for his trip to England has not been determined.

To capture the flavor of the rest of Hertz’s life, a newspaper column from 1940 serves best:

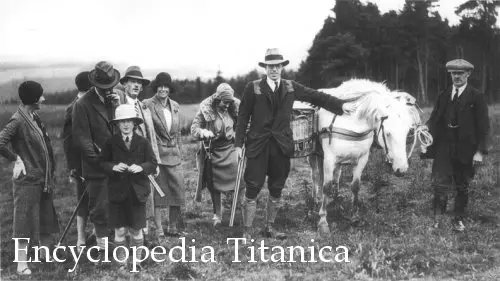

Served as a Captain in the British Army…was on the Lusitania when it was torpedoed…saw action in Gallipoli campaign…managed the negro heavyweight champion Jack Johnson…dropped a fortune trying to organize a Pan-American oil cartel…acted in silent movies opposite Marguerite Clark…has raced turtles in Miami and pigs in Los Angeles… introduced dog racing to Staten Island…recently completed a deal with Turkish Army for 20,000 donkeys…tried to buy the famous Tombs Prison and turn it into a wax museum…drinks only champagne for breakfast…dines chiefly on fowl…is president of a music publishing firm and owns a swing band… is now producing a Latin American film on Long Island…is a real estate operator…owns the Pegasus Polo and hunt Club at Rockleigh, New Jersey… club has sanctuary for famous old mares and stallions which have made names for themselves in theatrical work… one of these was Anna, a mare who carried the late Valentino through The Sheik…Anna died there recently and was interred with honors. Anna was also famous as an opera star…owns a nightclub named after the horse Sun Beau….great love is polo…says he will bring the son of the late Will Rogers and his polo team east soon to compete at Pegasus….dreams of a vast chain of polo fields from coast to coast “So polo can become the average man’s pleasure rather than the rich man’s fun.”

Mr. Hertz has recently been dubbed “Barnum on Horseback” by his press agents. They like to refer to him as “A cosmopolite Paul Bunyon” which no doubt he is. Certainly at 60 he defies analysis. He says he sleeps only three or four hours out of twenty-four, and consumes strong spirits at a rate of two quarts daily. His arena at Pegasus is said to be the largest indoor arena for rodeo and polo on earth. Actually, it is a vast airplane hanger which Mr. Hertz transferred to Rockleigh from Floyd Bennett Field. “My losses” he admits casually, “are about ten grand a month, but then what’s ten grand when you’re having fun?”This statement perhaps explains him better than anything anyone else could say.

There are several such articles about Hertz’s alleged frivolity, that span the final thirty years of his life. What is not contained in any of the copious press coverage, is exactly how Mr. Hertz made the jump from shipyard worker to beloved member of the New York area polo set as quickly as he did.

There are many serious articles about the man as well. He owned, for a time, the now-all-but-forgotten New York Yankees football team. He and a partner made a killing when they purchased the unwanted collection of U.S. Patent Office models, some dating back to the eighteenth century, and began direct marketing them thru the Gimbel’s Department Store in New York City. Among the first items made public was a patent applied for by Abraham Lincoln in 1849. Hertz quickly sold the model collection to a group of investors for $75,000.00, who were left holding the bag when interest in the curiosities dried up and sales collapsed. He offered NYC $850,000.00 for the slated-for-demolition Tombs prison, which he hoped to turn into a “museum of crime” in time to cash in on the 1939 World’s Fair: the offer was rejected.

Mr. Hertz was married at least six times. He mentioned, in 1915, that he had a wife and child in St. Louis. This could be Mollie, and Mary Madeleine, who returned from England with him in August 1916, although Mary is listed as being an infant on the voyage manifest. He later spoke of a wife who died in a train wreck. He entered the United States aboard the Aquitania, in 1938, with a wife named Modette, of Fort Cobb, Oklahoma. His immigration records from that voyage state that he became a U.S. citizen in 1937.

Douglas Hertz died in Novato, California, on November 28, 1967. His obituaries recalled him as a fun loving individualist who enjoyed polo and spinning a good story.

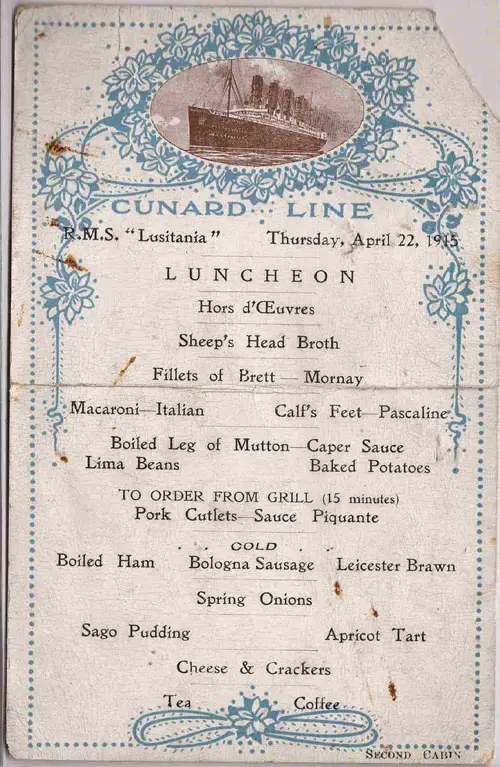

A menu from the Lusitania, April 1915

Dorothy Connor and Howard Fisher

“How wicked of me to drown when my mother needs me in Oregon.” These words echoed through Dorothy Connor’s head as she was dragged down by the sinking Lusitania. How did the Wellesley Graduate, on her way to help with the war effort, end up in such a precarious situation?

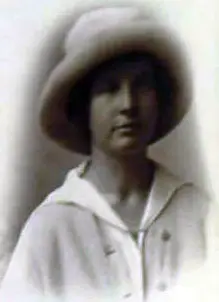

Dorothy Connor

Miss Connor lived the sort of life of which films are made. A typical well-to-do young girl of her era, her war experiences matured her into a purposeful, resourceful, and adventurous lady, and hers is among the most endearing of all Lusitaniabiographies. She was born in September 1890, to Charles and Katharine Connor of New Albany, Indiana. The Connors lived in a large Victorian home they named “Daisy Farm,” and led a prosperous existence. Dorothy attended school in Germany during an extended family trip abroad. Dorothy’s older sister, Sara Katharine, married Dr. Howard Lowrie Fisher, Dartmouth graduate, and Dorothy’s son believes that, as a five year old, she served as the flower girl.

Katharine Connor moved her family East, to Rye, New York, after her husband’s death around the turn of the century. Dorothy attended prep school, and was accepted to Wellesley, where she pursued a History degree. She was active on campus beyond her studies, participating in activities ranging from theatre to an eating club. She was a member of the Phi Sigma Sorority. She planned to become either a secretary or a teacher upon her graduation in 1912.

Katharine and Dorothy Connor moved together to Medford, Oregon, where one of Mrs. Connor’s sons was a successful orchardist. They bought a 55 acre farm in the Rogue Valley, and built a home there which they named “Sundown Hill.” They became active in Medford society: Dorothy took part in Society Vaudeville with golfer Chandler Egan as her partner. A photo of the two dancing together is on file at the Southern Oregon Historical Society. She jokingly wrote to friends at Wellesley, “I haven’t even taught Sunday School. I have no occupation, but I am very, very busy.”

But, the young woman was about to take her first steps towards independence. Dorothy had earned her degree in first aid by 1915. Her sister, Julia, was living overseas with her husband, the future Sir Harold Reckitt, and Dorothy, interested in helping with the war effort, decided to travel abroad and utilize her skills. Dr. Howard Fisher, her brother- in- law, was going overseas, and so it was arranged that the two would meet and take the next available ship- the Lusitania. They booked two inside cabins, E-50 and E-63, on April 28, 1915, for $285. Katharine helped Dorothy pack, and lent her a suitcase and a trunk. She told her mother, in jest, that she was, “afraid something might happen to them.”

Howard Fisher

Dorothy Connor and Howard Fisher arrived at the pier early, on the morning of May 1st. Fellow passenger, Thomas Home, recalled that there was a lot of baggage and that tickets were being thoroughly examined as people boarded the ship, which he believed caused a slight delay. Dorothy sent her mother a color portrait postcard, from the ship’s writing room, labeled Lusitania and Mauretania. She wrote: Expect a cable before Saturday or Sunday as we are not due in until Saturday. I thought it was Thursday, but since they have no competition it seems they don’t have to hurry! It is now eleven-thirty and they haven’t started yet though I don’t know why. I wish they would, it’s a rather chill, damp day…Dorothy.

Miss Connor went on deck to learn the reason for the delay but, after talking with a few people, did not find a conclusive answer. She returned to the writing room and, to pass time, composed a long letter to her mother. It read, in part, “The Lusitania is now being held up and there is a report that the captain has lost his nerve, but I think we will get off all right.” The delay, in fact, was because of the transfer of passengers, baggage, and crewmembers from the Cameronia, whose voyage had been cancelled upon her requisitioning. The Lusitania departed for Liverpool at about 12:30 in the afternoon.

Dorothy and Howard settled into the daily routines of shipboard life, and began to make friends and renew acquaintances. They met Charles Plamondon, Chicago social and civic leader and a friend of Howard Fisher’s brother, Walter. They found their tablemates in the dining room, D.A. Thomas and his daughter, Lady Margaret Mackworth, agreeable; they were returning to South Wales after a business trip to the United States. The crossing proved not to be as exciting as Dorothy had hoped it would, and she wrote in a letter to her mother, “I’d never seen a more uneventful or stupid voyage.” Margaret Mackworth recalled that the submarine threat had been discussed, and Dorothy commented, “I can’t help hoping that we get some sort of thrill going up the channel.”

Dorothy spent the Lusitania’s final morning packing. When she dressed for lunch, she chose a fawn-colored tweed suit with matching boots. She accessorized with her sapphire and pearl pins, and a treasured ring; an owl carved of gold, with diamond eyes. She, D.A. Thomas, and Lady Mackworth arrived on time, but Howard Fisher was delayed. Miss Connor recalled that she ordered squab. When Fisher arrived, he explained, “All trunks were ordered on deck by 10pm, so I told Dorothy that I would pack mine in the morning and get it over with. The trunk was packed with difficulty and delayed me.” He, too, ordered squab.

Lady Mackworth and her father finished their lunches, and then goodbyes were said. D.A. Thomas recalled Dorothy’s remark, and as he and Margaret made their way to the elevator, he commented “I think we might stay up on deck tonight, to see if we get our thrill.” (Dorothy Connor’s family revealed to Mike, that she consistently and emphatically denied having made the famous “thrill” remark. – authors)

Dorothy vividly described the moment the Lusitaniawas struck: It was while Howard was finishing his lunch and I was sitting waiting for him that the explosions came- two, apparently right under us. Everyone dashed and Howard and I did, too, though I did not realize for a minute that it was a submarine. Howard Fisher recalled the explosion: Bang! Came a rather dull sound like a soft blast, a slight rock and in a few seconds a listing of the ship to the side on which we were struck. Dorothy said ‘What is that?’ I replied ‘That is what we came after- a torpedo; we must go on deck.’

There was a severe list as they climbed the stairs to the boat deck. The two thought that it might be safer on the high side, and so exited through the port door. Margaret Mackworth soon emerged from the entrance: As I came out into the sunlight, I saw standing together Dr. Howard Fisher and his sister-in-law Miss Connor. I asked them if I might stay beside them until I caught sight of my father.

“Everything was confusion,” Howard Fisher would say of the scene at one of the port boats. “Men jumped on women and children trying to get into it.” Fisher would not allow Miss Connor to join the crowd, nor did she wish to after seeing the lifeboat overturn while being lowered. She later wrote to her mother: I won’t tell you about the lowering of the boats for the carelessness, the inefficiency, and the ignorance of the deck hands that did it was too terrible. Lady Mackworth turned to her friend and commented, “I always thought a shipwreck was a well organized affair!” Dorothy replied, “So did I, but I’ve learned a devil of a lot in the last five minutes!”

Dr. Fisher went below to grab life jackets for himself and Dorothy. He got as far as D Deck and was shocked to find: My cabin deck was already flooded, so I returned to the deck above, rushing here and there in the dark, for the electric lights had already gone out, trying open cabins for a chance lifebelt left behind by its owner. Miss Connor and Lady Mackworth waited on the boat deck for him to return. A crewman came by, announcing, “The gates have been closed, the ship is not sinking. There is no danger. Help is at hand. No more boats will be lowered.” The ship began righting itself, and a sigh of relief passed through the crowd. “Well, I guess you’ve had your thrill,” said Margaret. “I never want another one!” replied Dorothy.

Howard Fisher, hurrying back on deck, was accosted by a man who attempted to steal his life jackets. He did not succeed, and the Doctor joined the two women who waited for him. The Lusitania began to heel to starboard again. Dorothy noticed the concern on Margaret Mackworth’s face: One gets very close in three minutes at such a time, and just before we jumped I grabbed her hand and squeezed it to try and encourage her.

Dr. Fisher and Miss Connor went to the rail and prepared to jump, but Margaret Mackworth, afraid to jump, hung back on the perimeter of a small crowd, which soon blocked her way. Howard Fisher slipped through the rail, while his sister-in-law climbed over it. She said: We jumped just before the high side was submerged, and we were sucked down, down, down. I thought when we first shot in, that perhaps we’d come up again, but in the melee of things whirling around, I was caught by ropes and bars and all sorts of things that held me so fast I made up my mind that I was going to drown. Howard Fisher remembered being “Twisted and turned like a bug in a whirlpool.” Margaret Mackworth had time to undo her skirt, a dangerous impediment, before the water surged through the rails and over the side of the ship and engulfed her.

Dorothy Connor rose to the surface, unconscious, and drifted in her life jacket. Passenger Clinton Bernard, and an English nurse, spotted her from a drifting lifeboat and, suspecting that she was still alive, had her hauled on board. “Imagine my surprise to come to hours later and in my very dim consciousness discover that I was lying at the bottom of an upturned lifeboat.” She and the others atop the boat were rescued by a minesweeper, and were taken to Queenstown, where they arrived around 10pm. She used her remaining strength to walk to the Queen’s Hotel, where she calmly asked for “A single room and bath” and was surprised when “They laughed at me.” She recalled, for Adolph Hoehling, that she also received a lecture on being selfish. Her eventual roommate was a woman from third class.

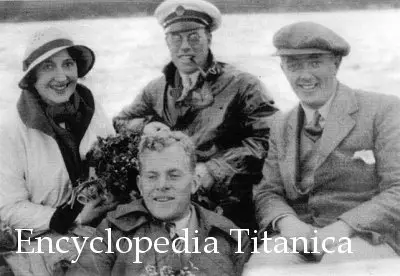

Clinton Bernard

Howard Fisher found Dorothy the following morning, and was so overjoyed that he fell on her neck with relief. Her injuries, although painful, were relatively minor: I’ve bandaged up my leg, which was rather badly gashed and has now gone to sleep. I seem to have bruised and wrenched every part of my body. Later, in London, a doctor would have to remove four large cinders ~ from the funnels~ from her ear. Dorothy’s clothing was returned to her cleaned and pressed, and when she visited with Lady Mackworth the woman commented that her outfit “looked as smart and well tailored as if it had just come out of the shop.” The foursome had dinner together, as they had every night aboard the Lusitania, and exchanged stories of their experiences during the disaster.

The following day, Dr. Fisher and Dorothy Connor departed for England. Miss Connor met Clinton Bernard aboard the train, and made plans to see him again. They were met, in London, by Dorothy’s sister, Julia Reckitt, who saw to their every comfort: She looks after me like a baby. Reflecting on items she lost, she most missed her owl ring: My dear little ring is gone- it must have slipped off when my hands got smaller in the water. But, she realized that they were just things, and that she and Howard Fisher were; the most fortunate people on the boat- we didn’t lose anything but things, and they don’t matter.

Miss Connor and Dr. Fisher kept in touch with a number of other survivors while in London. Clinton Bernard visited several times; they visited with Mrs. Lasseter after a chance meeting in Bradley’s store, with Dorothy later commenting that the disaster had aged the woman by ten years. Dorothy Connor and survivor Theodate Pope were part of a theater party that attended a performance of Rosy Rapture. And, she accepted an invitation to visit with Lady Mackworth and her father in Llanwern.

Dorothy returned to the United States in October 1915, aboard the Rochambeau. While she was home, she itemized a list of personal effects lost aboard the ship, among them:

1 Cross stole, fox $40

1 Lace evening gown $45

1 Silk gown $25

1 Velvet evening coat $50

1 Sapphire and pearl pin $25

1 Carved gold ring,

2 diamonds $50

for a total of $2,160.00.

She would file a claim against Germany for lost effects and pain and suffering, requesting $25,000 for the latter. One Lusitania-related health problem she testified to was a dilated heart. Her claim was settled, in 1924, for $15, 801.71.

Dorothy, the young woman who jokingly wrote of having “no occupation” in early 1915, and who survived a nightmarish experience shortly after, neither slipped into depression nor aimless frivolity in the months following her return to the U.S. 1916 saw her back in Europe, near the battle front, helping her sister, Julia, run the canteen she had established at Braine, not far from the Ainse River. She embraced the hard work and remarked, “The work is most interesting and I already feel very much at home.” Her duties ranged from rolling cigarettes to serving coffee: Doing the cooking and looking the part of an immaculate and dignified directrice is often difficult. She was amused by the conduct of the soldiers, who could be rowdy and who would sometimes not omit indelicate lines from the songs they would sing. She said that it was just as well that she, “did not know all the fine points of the French language. Same old story of keeping one’s eyes on the skyline.”

She wrote that when she looked out of her window, she saw: Paris buses painted gray, camions, camionettes, kitchens on wheels; gun officers on horseback and in carts and automobiles, horses going to water in the sewer which skirts our garden….I see two huge guns, one named “Marie” and the other something else, followed by ammunition wagons. Exploring the countryside, she found herself behind three guards escorting German prisoners: “Are you a prisoner, too, madamoiselle?” the French soldiers asked jokingly. She visited Brenelle, “a sweet little town half shot to pieces in the attack last month.”

Dorothy described moments of great excitement, in her letters home. The police came to search the canteen looking for a deserter. A German plane crashed in the woods after falling from a height of 3000 feet: “The German machine fell about ten-thirty in the morning. About one- thirty we found it in the woods- or what was left of it…one man escaped with a broken arm, while the other was killed.” The soldiers encouraged Dorothy to “come right up” and view the body, but she declined.

Shrapnel once struck the doorstep of the canteen and four men were killed right across the street. The pressure at the canteen proved to be too much for many staff members, and the turnover was high. Dorothy dutifully wrote home to her mother, and joked that she, “would be glad to hear what you do when Dorothy is away and you do as you please.”

Dorothy Connor was awarded a medal, her family believes a Croix de Guerre, for her bravery, at the war’s end. Miss Connor married Lieutenant Greene Williams Dugger, Yale graduate, in 1923. They met when Dorothy and her mother were guests aboard a battleship, while traveling in Panama. The Duggers had two children; a son, John, and a daughter, Mary Anne. Being a Navy family, they moved frequently, and Dorothy wrote to her Wellesley friends, “Travel is such an every day occurrence to me.” John would graduate from the Naval Academy, and Mary Anne from Wellesley.

Greene Dugger died in August 1941. Howard Fisher, Dorothy’s beloved brother-in-law, died in July 1946. Dorothy enrolled in George Washington University, taking courses in education. She was a member of the Colonial Dames of America, the Washington Wellesley Club, and the League of Women Voters. She once said, “I still find the world full of interest and excitement.” When she passed away, on August 9, 1967, her friend, Nell Cohen, would say in tribute, “It is good to know that right up to the end of her life she maintained her beauty, her charm and her dignity.”

James Reckitt, Dorothy Connor’s brother in law, published a book about his wartime experiences: V.R. 76; A French Military Hospital in 1921. Dr. Howard Fisher contributed this account:

A RECOLLECTION

The outbreak of the Great War found me in distant Oregon. Though I knew but little of the warring nations, I was, like most Americans, intensely affected and mentally placed my sympathies where they have ever since been. I was pro- British from the time the first cablegram found a place in the daily papers.

I was pro-British for several reasons. First, I had lived among English people in British India for six years and had learned to appreciate their real worth; I had an English brother-in-law; I had lived nine months as a student in Berlin and despised the Prussians and, finally, the rape of Belgium was a crime against humanity that could not be forgiven. Then, as the months went by, though the war touched neither me nor mine, the brutality of the Germans, the call for medical men and more medical men, quickened a slumbering impulse to thrust myself into the conflict.

When, in 1915, Mr. and Mrs. Reckitt commissioned Dr. Lewis Conner to select a medical staff and equipment for a field hospital to operate in Belgium, I wrote Dr. Conner. When my letter reached him, the staff was full and for the first time I realized how great was my desire to serve, how keen my disappointment.

Again the days went by as usual. I had settled down to a normal life. Then came a cablegram to me from Mr. Reckitt, “Come at once.” I was to take a part in Germany’s defeat.

There were many notable passengers on that last voyage of the Lusitania, among them Lord Rhondda (at that time Mr. Thomas) and his daughter, Lady Mackworth. Madame du Page, the wife of Belgium’s Surgeon-General, was also on board. So long as I live I shall never forget this lady’s sad, anxious face. She had just finished a tour of the United States and was returning to her ravaged country with a money contribution for the Belgian hospitals. Had she some prophetic vision of the coming disaster? Her son she had given to the war. Her husband was daily in the fighting-line. She was lost with the sinking of the ship, but her frail body reached friendly hands, I am told, and she found a last resting-place in the soil of her beloved country, out on a lonely and desolate stretch of sand dunes that Belgium still held as her own.

Lady Mackworth I saw in the wild confusion that followed the wounding of the ship and its great list to starboard. She was alone, anxiously searching for her father in the crowd that rushed here and there. She, with another woman and myself, stood on the larboard side and, after watching the ill-fated attempts to lower the lifeboats, decided to jump

into the sea rather than await the terrific rush and impact of water that would follow as the ship plunged headlong to the depths.

Lord Rhondda was returning from a munitions mission to Canada and the United States. He was very grave, ate sparingly and neither at table nor elsewhere was inclined to casual conversation. That he was masterful and shrewd in his own affairs and in those of his country, there could be no doubt, but he met his match in a raw Irish- American in the Queenstown Hotel on the night of the disaster.

It was the one humorous incident of that tragic day.

It was past midnight. The hostelry was full of the Lusitania’s ill and wounded, who were just finding the quiet and rest so much needed. There were but three of us in the parlour, Lord Rhondda, the Chief Surgeon and myself. I had said good-night and was lying under a table rolled up in a blanket, the other two were engaged in quiet talk, when in burst this wild Irish-American. In some miraculous way he, his wife and little child had been saved from death, though they had all been swept into the sea. He was celebrating his own, and their, escape. His pockets were full of whisky, his stomach equally full. He was celebrating and, willy-nilly, the two men must celebrate with him.

He burst into song and my companions added angry remonstrance to their refusal to drink.

“Drink with me and I’ll shut up.”

A second curt refusal followed.

“Then I’ll raise hell!” said the tipsy, hysterical man, “for I still have my wife and baby.”

Then he spied me under the table and dragged me out as he would a sack. “You too,” he said, “drink! ”

“No!” I replied.

As he was about to let out a war-whoop, Lord Rhondda reached for the bottle, took his drink and the surgeon and I followed in his wake.

There was one other bit of humour incident to the sinking of the Lusitania that still makes me grin when memory brings back those tragic days. That was the crestfallen looks of the porters as they ran along the London railway platform, ready to pounce upon the luggage of the travelers.

But it was the Lusitania special and of luggage there was not a trace.

The reception of my sister-in-law and myself at our hotel was no less comic. The night watchman at the door all but refused us entrance, for we were a bedraggled pair of vagabonds, disheveled from a sleepless night and without kit; I with a black eye and garments much the worse for bad usage. The watchman stood perplexed. I looked at my sister-in-law, with her little paper bundle under her arm, and grinned at what I saw. She looked at me and my queer make-up and smiled at the picture she beheld. Then we mentioned the Lusitania and the doors flew wide and hot baths, food and soft beds made us forget we were among strangers.

D. A. Thomas

D. A. Thomas, father of Lady Mackworth and tablemate of Dorothy Connor, left this account:

Let me give you a consecutive narrative which I hope will assist the Government, the public and the Cunard Company to come to correct conclusions. I will avoid harrowing details as much as possible.

We got on board the Lusitania at nine a.m. on Saturday, May 1. She had been advertised to sail at ten: she actually left the Cunard pier at a little after twelve noon. We had seen in the press that morning an advertisement inserted, it was said on the authority of the German Embassy at Washington, notifying passengers sailing on British vessels that they did so at their own peril and that the German Government would accept no responsibility for anything that might happen to the passengers who disregard the notice after reaching the war zone. Curiously enough, this advertisement appeared in the New York Times in the column next to and in fact directly along side the advertisement of the sailing of the Lusitania that morning. There also appeared a statement by the representative of the Cunard Line pooh-poohing the threat, and giving an assurance to those sailing that the Lusitania would be well taken care of when she reached the danger zone.

Some of her passengers are stated to have received private intimation from German sources of the danger, but I received no such notice myself of any kind beyond what I saw in the press.

Well, I do not claim to be possessed of more than average courage, and I confess I felt some degree of nervousness when approaching the Irish coast, in fact, I determined to remain on deck with my daughter the whole of Friday night.

At the same time, after the assurances we had received and other information given apparently with official authority, and also after the statement that the Transylvania, a boat belonging, I believe to the Anchor Line, had been conveyed recently after reaching Ireland, I had no serious apprehension of the terrible disaster that afterwards occurred.

We had a smooth passage from New York. Only a couple of occasions did the sea become in the least bit rough. The weather was a bit foggy soon after leaving New York and again foggy shortly before reaching the Irish coast. The Lusitania hooted, and I remember remarking to a friend on board, “That gives our whereabouts away, but I suppose we are being well looked after.” That was on the Friday morning, when we were in the fog.

The fog lifted, the sea was particularly smooth, and the sun was shining very brightly without a cloud in the sky when we sighted the Irish coast about eleven o’clock. We appeared to be about fifteen miles off the Irish coast, sailing a course a good deal further away than on her outward trips when I had crossed before.

We left the luncheon table a little after two (ships time) and had barely reached the lift, there being a number of passengers about, when we heard the torpedo strike. It did not make any great noise where we were standing. I had always been led to believe that the Lusitania was unsinkable, and that it would take more than two torpedoes to finish her. We all realized immediately what had happened. I went up to ‘A’ deck to get more accurate information, and as we had previously arranged, my daughter at once went to her cabin to get her lifebelt.

All was quickly turmoil on the port side of the A deck. The boat soon began to list and I went down below to get my lifebelt. I did not succeed in reaching my cabin which was one of the parlour suites on the port side of B deck. I again went to A deck. By this time the steerage passengers had rushed up onto A deck, and they and others were crowded around the boats. There was absolute confusion everywhere, and an entire absence of anything in the way of discipline or organization.

I may say here that no attempt was made to close the port holes in the dining room deck.

I was told that the bulkheads had been closed, but in view of the very rapid submerging of the Lusitania I should require some strong evidence of this. I came quickly to the conclusion that my chance of getting into one of the boats was very remote. I, therefore remained away from the crowd, and a friend, meeting me and seeing I had no lifebelt, volunteered to go to his cabin and get me a blow-out belt.

We went together to his cabin and got it. I blew it up and put it on, and it did not give me any impression of security, as I felt it would at any moment collapse. I, therefore, determined to make another effort to get into my cabin. I succeeded, for the staircase and passages were quite clear. To my astonishment I found that the lifebelts I had left on the bed were gone! It appeared afterwards that one of the lifebelts had been taken up by my daughter to give to me, but she failed to find me, just as I failed to find her. The other lifebelt had been taken by someone.

I however, remembered that there were several in the wardrobes, and on opening these I found three. I put one on, and two of the Officers coming into the room at that moment I gave them one each. By this time the list on the ship had greatly increased, and, finding it difficult to walk up to the port side, I went to the starboard side on deck ‘B’, which by then was almost flush with the water.

Just opposite what was known as the grand staircase a boat had been lowered and was about three parts filled with people. It was about four or five feet away from the ship’s side, and was still held by the davits. There were a couple of women and a child opposite the boat. One of the women and the child jumped into the boat. The other woman became hysterical and screamed, “Let me jump, let me jump!” but was afraid to jump. I pushed her, and I made her jump, for I could not make my jump until I had seen her in the boat. Fortunately she reached the boat safely. I then put my foot on the ropes and made a jump well into the boat, which was then six or seven feet away from the ship’s side. On clearing the wreckage I helped to pick up two men and a girl, Miss Luny, who were clinging to the side.

We quickly cut ourselves away. Then another danger, which at the moment looked quite insurmountable, occurred. One of the huge funnels slowly descended towards the middle of the boat, and it did not look as if we had the smallest chance of escaping it. What happened then I can hardly say, but I shouted loudly to many nearest to me to push her away. This was done, and the funnel seemed to slide away from us as the ship went down. We were then between two funnels.

Though I believe I kept my feelings perfectly under control, I was suffering intense excitement and under such circumstances it is difficult to keep time accurately, but it could not have been more than fifteen minutes after she was first struck when the Lusitania went down bodily. I thought that it was inevitable that the suction would have brought us down, but it is a very remarkable thing to my mind that the sinking of the ship produced no effect at all on the steadiness of out boat, which then contained 50-60. It could not have held any more.

We at once moved away in a sort of way. As an old rowing man I tried to put a little organization into the business, but this was resented by two or three of the crew of the Lusitania who were with us, so I left it to them. The sea was absolutely calm; otherwise we should not have kept afloat for five minutes. The boat leaked, and we began to take in water. I helped to bail this out. It gained on us until it was up to our ankles. But after about twenty minutes bailing there was no more trouble in that direction.

We rowed in a sort of fashion for the coast, which appeared to be about fifteen miles away south west of Kinsale lighthouse, which was plainly visible in the sunshine. Soon we observed a little sailing vessel, and we made for her, going at the rate of a mile or so an hour. The smack was coming directly towards us but there was so little wind that her progress was also painfully slow.

By the way, before I forgot to say that I had set my watch to the ship’s time some little time after noon that day, and it pointed 2:25 immediately after the Lusitania sank.

We also saw the smoke of a steamer far away to the south, but after appearing to get nearer it went away again, evidently not having seen any of the boats. On clearing the wreckage I counted nineteen boats, some of them turned upside down and large pieces of wreckage with a number of people on each. In about an hour and a half, somewhere before four o’clock, a sailing boat came up to us and turned out to be the Wanderer P.L11 a Manx fishing boat of fifteen or sixteen tons. Captain William Bell, with a crew of four or five.

Captain Bell was an intelligent man. He took about 50 survivors off the boat, and about eight or ten of the crew, including two or three stewards, returned to the scene of the disaster in the boat. We, on the Wanderer, also moved in that direction, and picked up survivors on two other boats, casting the boats adrift. By this time the little smack could hold no more. We however took two more boats in tow.

A number of steamers were now coming up fast from several directions. The first one reaching the scene of the disaster about five minutes past five. We were some miles away but I could see that the steamers stood around in a circle with a diameter of several miles for some little time. Then I saw them all move in the direction of the scene of the disaster. We were then taken off by a tug called the Flying Fish and made for Queenstown, which we reached about 9.30 pm.

I had not seen or heard from my daughter since we parted at the foot of the staircase of the deck, she going for her lifebelt. I looked round for her for some time before going back for my lifebelt the second time but failed to see anything of her in the crowd and confusion. Also in my boat was my secretary Mr. Rhys-Evans. May I never suffer such agonies again. At about eleven o’clock the Steward, T. Godfrey of Seaforth, a gentleman who I am never likely to forget who had been waiting upon us on the Lusitania came up to me to say that Lady Mackworth was on a boat, the Bluebell, and she was safe but greatly exhausted. Captain Turner was also on the Bluebell.

David Alfred Thomas, Lord Rhondda, died in Wales, at age 62, on July 3, 1918. His daughter, Viscountess Margaret Mackworth, died in London on July 20, 1958, at the age of 75.

Robert Rankin

“When G.E. Co. claims Bob, the electrical world may expect a shock.”

……Cornell, 1904

That jocular prediction came from Robert Rankin’s Cornell class year book. He was born on March 23, 1882, as the first-born son born of George and Sarah Rankin of Ithaca, New York. Rankin was fascinated by electricity, and upon graduating high school he enrolled at Cornell University. When he was not studying, he was actively involved in sports, which resulted in multiple scholarships; so many, in fact, that his friends joked that he was bankrupting the Cornell treasury.

Robert Rankin

Rankin began working for Westinghouse soon after college, all the while experimenting with electromagnets and their properties. He was hired by the San Paolo Electric Co., of Brazil, which meant frequent travel.

He met socialite Enid Scott on a voyage to South America. Enid’s father was Simon Scott, a New York merchant and art collector. She and Robert married the following year.

Robert Rankin became friends with Dr. Frederick Stark Pearson, owner and manager of Pearson Engineering Corporation. Rankin’s professional dealings and friendship with Dr. Pearson led him to take the Lusitania on her last voyage. The Doctor and his wife had already booked passage, and recommended to Rankin that he should make the crossing as well.

May 1st was a dull, overcast day and Rankin did not wish to linger on deck. He was led down a maze of corridors to inside cabin E-43.

Mr. Rankin found his table companions for the voyage agreeable, and became fast friends with Clinton “Bill” Bernard, who told him that he was on his way to Greenland on a geological expedition. Rankin also spent time with the Pearsons, Robert Dearbergh, and Thomas Bloomfield.

The afternoon of the 7th was a clear, sunny day and at about noon, Rankin went to the writing room to write a long letter to his wife. Dr. Pearson passed through while he was writing, and stopped to talk with him. They discussed the sudden alteration in the ship’s course. Robert Rankin later said, “The ship turned northward from the course she had been holding making a huge semicircle and heeling well over to port.” The letter finished, he took a quick walk along the boat deck before lunch. He saw Fred and Mabel Pearson taking a stroll as well.

Robert Rankin was standing on the starboard side at some point after 2 pm, with Thomas Bloomfield and Robert Dearbergh, when one of them caught a glimpse of something unusual. “There’s a whale,” he heard. Looking out onto the dazzling blue sea, he knew at once what the black ridge was. A white, foamy streak shot out from the submarine.

“It looks like a torpedo,” Dearbergh exclaimed.

“My God, it is a torpedo,” said Bloomfield.

The three watched, as it cut through the water. Rankin described the excitement of the moment in great detail:

It came straight for the ship. It was obvious it couldn’t miss. It was aimed ahead of her and struck under the bridge. The explosion came with a terrific crash, clear through the five decks destroying the boiler room and the main steam pipe….A mass of glass, wood, etc came pouring on our heads, 200 feet aft. We ducked into the smoking room shelter and I never saw my companions again.

Robert Rankin believed from the start that the Lusitania was doomed. He crossed the smoking room to the portside, where he aided some men who were trying to push a lifeboat over the edge. But he thought that it was a useless task, for the ship was listing too far to starboard, and he abandoned this effort. He entered the companionway and made his way down, trying not to bump into the people who were rushing up the stairs. He got as far as D deck and heard the disconcerting sound of water very close to where he stood. Looking down, he saw that E deck was already flooding. He crossed the darkened passageway on D deck to a porthole, and to his horror, saw that the water was within twelve inches of the port.

Rankin came across Clinton Bernard in the stairwell. Bernard asked him, “Have you a life preserver?” to which he shook his head, “No.” They tried a few cabins, but found that the life vests were gone. The two decided that if they found one, they would share it, “fifty-fifty.”

The two friends found quite a few passengers milling about and waiting to be told what to do, as they walked along B deck. They mounted the stairs to A deck and watched the crew beginning to load boats along the starboard side. Boat # 1 drifted away with what appeared to be just one person aboard, to their dismay,. Rankin came across one of those “doughnut life preservers” attached to the rail and presented it to Bernard. They prepared to jump overboard with it when a steward approached them and claimed that there was an old lady who needed it. The gentleman unselfishly gave it away.

The last minutes were a blur to Rankin:

By this time the boat was sinking rapidly and Bernard said, ‘Goodbye old chap’ and grabbed me by the hand at the same time pulling out his money and throwing it away. The sixty foot deck was, by now, within six to ten feet of the water and I pulled off my coat and jumped, feet first, as far as I could and started to swim on my side. Looking straight up I saw the funnels coming over and thought that I would certainly be hit on the head. Then the funnels went back and the bow plunged and the ship went down.

The water felt like ice to Rankin. He noticed that he was covered with a layer of soot from the funnels. He swam to boat #11, which was packed with more than sixty people. The assistant deck steward pulled him in, despite the crowding. Boat #11 drifted with the tide and wind, for it had no rudder. Finally, the Wanderer, of Peel, came to the rescue and pulled them aboard. They were later transferred to the Flying Fish and taken to Queenstown.

The arrival at Queenstown was striking, as the wet and weary survivors walked between a line of townspeople. The crowd cheered and applauded as they made their way forward. Rankin felt a lump in his throat as the magnitude of the tragedy hit him. A “jacky-tar” gave him a drink of hot whiskey and put him to bed.

The next day, he made his way through the town looking for his friends. He found Clinton Bernard, who had swum to a collapsible and rescued many people, among them Stanley Lines and Dorothy Conner. Rankin found Dr. Pearson lying in a makeshift morgue and arranged for his embalming. Rankin and another shipboard acquaintance, Robert Timmis, motored over to Kinsale the Sunday after the disaster to help identify bodies, but found no one that they knew.

He gave a brief description of his experiences to the American Counsel, which was sent to the State Department in the form of a deposition:

At 12 pm ship began zigzag course off Irish coast. Walked deck till 1:30. Went to lunch 20 minutes. Arrived on rear starboard A Deck at about 2:00 pm, ships time of night before. At exactly 2:10 pm one of our group of four sighted submarine rising about 1/4 mile to starboard bow. Lusitania going slow all morning. Had been blowing fog horn till about 10:00 am and was still going about 15 knots. Torpedo left submarine almost instantly after sighted and traveled rapidly toward boat, leaving white trail. Struck ship not far from a line below the bridge and through boiler room. Explosion tore through deck, destroying part of forward lifeboat. A boiler exploded immediately. There was no second torpedo. Boat listed immediately and began to fill through open ports as well as the hole caused by explosion. Ship sank at 2:33 by watch of passenger who jumped in sea. Torpedo fired without warning and while most of passengers were below at breakfast.

Mr. Rankin arrived in London on Monday afternoon, intent on keeping his business appointments, although he had lost all his papers. He returned to the United States aboard the St. Louis, along with survivors Oscar Grab and Charles Hardwick; they arrived in New York on June 7, 1915.

Oscar Grab

The Lusitania disaster did not deter Rankin from traveling. He left San Paolo Electric, and he and his wife moved to Peking, China where he was appointed vice president of both Anderson Meyer and Co and the Willard Straight Co. He also served as the director of the Chinese American Bank of Commerce. Relations between Robert and Enid deteriorated, and they separated and then divorced. His ex-wife moved back to New York and wrote a book titled Dominions of the Air. It examined the causes of war and offered suggestions on preventing future wars. She passed away a few years later at age forty-three. Apparently Rankin and Enid adopted a Chinese child named Peter, but he is not mentioned in either of their obituaries.

Robert Rankin retired in 1920 and began traveling, to relax and to forget about his failed marriage. He met a woman named Hilda Master Rigby and they were wed on February 24, 1923. They settled in Angmering on Sea, Sussex, England.

Robert Rankin filed a claim for compensation for lost effects and was awarded $1,362.00.on February 21, 1924.

The Rankins moved to St. Catherine’s, Ontario, where they remained for many years. Robert became a father, at age fifty-two, to a girl who they named Virginia. He went to Washington, D.C. during World War II, to work as an engineer for US Government, and he became a technical adviser to Evans International Corp after the war. Robert eventually returned to retirement back in St. Catherine’s, Ontario. He began vacationing in Provincetown, Massachusetts in old age, where he could, no doubt, look back and smile at life filled with promise well realized. Mr. Rankin passed away in Provincetown on August 10, 1959 at age 76.

James Tille Thompson

James Tilley Houghton was born in Saratoga Springs, New York, on July 23 1885. His father was James Warren Houghton, a Justice of the Supreme Court of the State of New York. He was prepared for college by private tutors, and went to Harvard University in the fall of 1904, where he was a member of the Pi Eta society and took lead roles in several of the society’s shows. He received his college degree in 1908 and three years later his medical degree.

Houghton went to work at City Hospital in Boston, Massachusetts. It was there, in February 1913, that his father was admitted for surgery after falling ill with appendicitis. The operation was not a success and Justice Houghton died on February 14, 1913.

Dr. James Houghton was working for the Belgian Red Cross by 1915, under the supervision of Dr. Antoine Depage at his hospital at La Panne. He boarded the Lusitania on May 1st, joining Marie Depage, wife of Dr. Depage. Madame Depage, who was the head of the Belgian Relief Society, had been touring the United States, appealing for funds to help the Belgian relief effort.

Two telegrams were waiting for Dr. Houghton in his cabin, E64, which read: Best wishes, fine trip and speedy return. Cable address, will miss you terribly. God protect you – Hugh Caroline. Goodbye and good luck – Teresa.

The voyage passed uneventfully. Houghton renewed his acquaintance with Lindon Bates Jr. and Major Frederic Warren Pearl, both of whom worked for the Red Cross. He also met fellow a Harvard graduate, Richard Freeman, class of ‘09. Dinner each night was spent in the company of Madame Depage, and Theodate Pope and Edwin Friend, both of Connecticut.

Houghton was interviewed upon reaching Queenstown, and gave the following account of the disaster:

I may say that I had a dreadful foreboding that we were torpedoed and was not surprised when I got on deck to be informed by an Officer that we had been attacked by a German submarine. By the time I had reached the deck the vessel had decided list to starboard. I remained standing on the deck for a moment or two and was joined by Madame Depage.

The boats were by this time being lowered. An Officer told us that there was no danger. The vessel would be heading for Queenstown and would be beached there, if necessary.

The liner was again struck, this time forward of the main bridge. The first torpedo had struck midships. The second attack was evidently of a more deadly character than the first, as quite suddenly the big vessel began to settle by the head. Orders quickly came from the bridge to lower all the boats. This work was at once commenced.

Women and children were being rushed to the boats and were being lowered, some of them successfully, but others not. Many people were thrown into the sea. I saw the time to leave the ship, now well down by the head. I said to Madame Depage that we had better jump overboard and trust to be picked up by one of the rafts or lifeboats. This we both did. As I struck the water my head came into contact with a piece of wreckage which stunned me and I commenced to sink.

Happily I came to the surface again and I struck out for a damaged raft that was not far away. My first thought was to try and see Madame Depage but no trace of her was to be seen and I can only conclude that she was drowned.

Quite a number of people were on the raft and it was sinking under us. One poor fellow lost his reason altogether and jumped into the sea and was drowned. We were about 100 yards from the Lusitania when she foundered. It was an appalling sight to witness as her decks were still crowded with passengers frantically rushing about in a frenzied state. The spectacle in the water was even worse when scores of people were struggling to keep afloat and some shouting for help. But we could not give any assistance.

We were eventually picked up by a trawler and transferred to the tug Stormcock. We were then brought ashore at Queenstown. It was an awful experience and I thank providence for my escape.

Marie Depage

Marie Depage was lost, but her body was found and identified. Her husband traveled over from Belgium, and her body was embalmed and taken to the La Panne hospital, where she was buried. An interesting aside about Madame Depage, is that on May 8th 1915, a completely believable and lucid survivor account given by this definite victim ran in several newspapers, which highlights one of the pitfalls of newspaper-based research.

The Boston offices of the Cunard Line sent a telegram on May 11th; Ask Dr Houghton, survivor when he last saw Richard Freeman and if Freeman left the steamer uninjured. The same office received a telegram on the 13th stating: Dr Houghton states he and Freeman jumped into the sea together and were separated, Freeman was uninjured then, but regret there is no trace of him. Freeman did not survive the disaster, and his body was not recovered. The “poor fellow” who lost his reason and jumped into the sea was recognized as another first class passenger, George Ley Vernon.

Houghton traveled on to London, where he went to the American Embassy, and then returned to the United States aboard the Cameronia, arriving in New York on June 7th. He never returned to La Panne to help Dr. Depage.

Houghton was eventually awarded $12, 372, 00 in compensation as a result of the disaster.

He went to the Mexican border in 1916, with the Old 69th Regiment of New York, under Colonel William Haskell, and it was also in that year he married Mabel Parsons. The following year his son James Tilley Houghton, Jr., was born.

He immediately returned to the 69th Regiment when the United States entered the war in 1917, and traveled overseas with them in the Rainbow Division. He returned to the United States when the war ended.

Houghton went to the South Sea Islands in 1921, on a treasure hunt. In 1923 Colonel Haskell asked him to join his staff on the Red Cross Relief work in Greece. He worked in a plague-infested area of Macedonia. He was knighted by King George of Greece and received the Order of St George. Houghton relocated to Honduras, in 1924, to take charge of a new hospital at La Ceiba. He knew that a revolution was under way, but went just the same. He found the hospital woefully inadequate, with only an emergency kit and a few medicines with which to treat and operate upon 450 wounded. He performed several successful operations using only a razor blade.

Houghton chose the wrong side of the revolution. He managed to escape capture by retreating into the forests, and eventually escaped by boat to the safety of Guatemala. Houghton resumed private practice upon his return from Central America, and held an important position within the Travelers Insurance Company. He divorced his first wife, and in 1929 he married Caroline H. Pritchitt. Together they had a son.

Dr. Houghton became seriously ill in early 1931. His family and friends told him that he was suffering from Undulent fever, but in fact he was suffering from streptococcus in the blood stream. He died in New York City on March 25th, 1931, at the age of 45.

Fullerton Riemer Boyd

There was a Lusitania crew member with an interesting link to Germany aboard the fatal voyage.

Fullerton Riemer Boyd, 37, listed on the crew manifest as a barkeeper, had led his family in Joliet, Illinois, to believe that he was the Lusitania’s assistant purser. His family had not seen him in nine years, although his sister- in -law had visited with him aboard the Laconiain 1913. They received a letter from Boyd, mailed on May 1st, in which he wrote that he was not in the least apprehensive about the coming voyage, and that the passengers were being warned.

Fullerton’s name did not appear in the initial list of those saved, which was reprinted in midwestern newspapers. His brother-in-law Edward Kobbe, an official of the New York office of the Hamburg-American Line, was able to determine that Boyd had survived, and sent his family a telegram reading “Thank God Fullerton Is Among The Rescued.” Kobbe told his in-laws that he had received the news through his London offices.

Boyd died in Southampton, England, on October 17, 1929, at age 51.

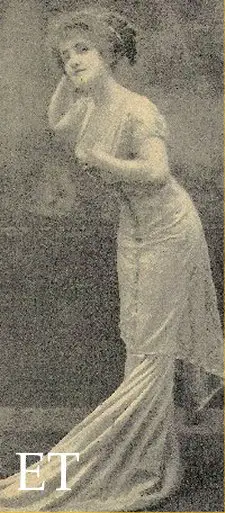

Josephine Mary Brandell

Josephine Mary Brandell was a rising stage star in 1915.

She was born November 26, 1891 in Bucharest, Romania. Her family came to America in 1900 and settled in New York. She dreamed of stardom, like many young people, and made an attempt to break into show business on the New York stage while in her early teens. However, she abandoned her efforts to establish an acting career when she married Dr. Bernard Black Brandeis, on February 15, 1907, at age fifteen. The marriage was short lived and the couple divorced in September 1910.

Josephine became involved in the theatre again, following her divorce. She was soon cast in a production of a comic opera by Johann Strauss, Night Birds, which toured Europe and America. A newspaper compared Brandell to the star, Fritzi Scheff, saying that she was ‘commensurate with Miss Scheff’s prestige.’ She was starring in the London Opera House’s production of Come Over Here by 1914,.

Miss Brandell crossed the Atlantic aboard the Lusitania several times. She was aboard the Lusitania’s February 1915 crossing, and chose the Lusitania, again, for her return to London in May. Josephine’s friend, Mabel Crichton, was booked on the same sailing. Mrs. Crichton was to provide Josephine Brandell with much emotional support. The actress was among the handful of passengers who remained worried throughout the crossing.

Josephine did not feel confident that the ship could outrace a submarine and, as she put it, was “in a state,” for a good part of the journey. She and Mabel became acquainted with their tablemates; Max Schwarcz and Francis Bertram Jenkins. She could not get over her feeling of dread, despite the pleasant company. Jenkins did not alleviate her fears by pointing out the lack of lifebelts.

|

| Josephine Brandell Daily Sketch Jim Kalafus Collection. |

|

| Mabel Crichton Courtesy of Paul Latimer. |

I had just finished making a collection for the musicians and sat down to finish my lunch where Mrs. N. Crichton , Mr. Jenkins and Mrs. Schwartzs, an American, were sitting, when I heard the explosion. We all jumped up, poor Mrs. Crichton exclaiming “They have done it!” In fact, I was nervous during the whole trip; so much so that I kept worrying my friends about fearing the submarines.

Thursday night I was in a state that I could not sleep in my own cabin, so I asked Mrs. Crichton if I could sleep in her cabin. Poor soul, she was only too happy to be of any assistance to me and did all she could during that whole night to quiet my nerves.

The next morning, I heard the hooting of the horn, as it was foggy. Everything went well until I sat down to lunch when the explosion occurred. The people rushed for the stairs. I heard someone shouting to be calm. I looked up and saw that it was one of the captains. I cannot say whether it was the first or second.

When we finally reached the top deck, I saw very few of the first class passengers. I was simply horrified with fright. Mr. Schwartz’s trying to calm me, when Mr. E. Gorer (the art dealer of Bond Street) rushed over to us and put a life belt on me, which was my means of being saved, and told me to be brave. He returning for other life belts and Mr. Schwartz, after putting me into the boat where Mrs. Crichton was already sitting, went to help other women. That’s the last I saw of those two brave heroes.

Just then, our boat was lowered but immediately it hit the water it upset throwing all its occupants out. About six were saved from that boat which contained sixty or seventy passengers.

The sights I saw when that boat upset is too awful. Words cannot describe it. A rope was thrown to us, which a few caught hold of. I then remember a few of us getting hold of an oar, but some of them soon dropped off. The cries for mercy, the people drowning and coming up again within three minutes time barely touching me was too terrible.

Somehow, I caught hold of a deck chair which was floating near me and held on until I became numb when I was picked up by Mr. Harkness, the assistant purser, who afterwards told me he thought I was gone when he first looked at me.

Josephine Brandell came ashore in hysterical condition, and one survivor in the same hotel room later remembered asking her to calm down. She found Francis Bertram Jenkins the following day, but there was no sign of Mabel Crichton, Max Schwarcz, or Edgar Gorer. Josephine took it upon herself to inform William Crichton of his wife’s last moments. He could not be consoled, and passed away a year later.

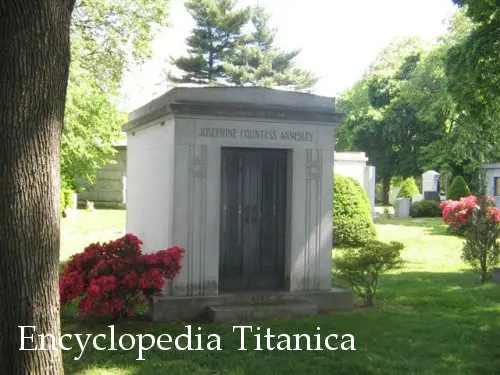

Josephine did not fulfill the promise of her early stage career. She chose not to pursue starring roles after the disaster, and acted only occasionally. She helped with the war effort, and following the Armistice, she accepted the proposal of John Ormiston Lawson-Johnston. They were wed on May 19, 1920. The marriage was not a happy one and ended in divorce. She was married yet again to George John Seymour Repton on June 1, 1929. George Repton attained the rank of Captain during his service in the Irish Guards. Miss Brandell was well known during World War II, as the founder and chairwoman of The American Friends of Britain. Captain Repton died on May 10, 1943.

Josephine married once again, on December 7th, 1945, to Beresford Cecil Bingham Annesley, 8th Earl Annesley and 9th Viscount Glerawly. He was a Pilot Officer in the service of the Royal Air Force Volunteer Reserve during World War II. He had previously been a Lieutenant in the service of the 6th Battalion Royal Fusiliers. Their marriage lasted until his death on June 29, 1957.

Countess Annesley returned to the United States and spent her final years living in New York City, dying there in August 1977.

|

|

|

Josephine Brandell age 15

(Shelley Dziedzic) |

Josephine Brandell’s Grave at Woodlawn Cemetery, Bronx, NY

(Michael Poirier) |

Maude Thompson

Maude Thompson, one half of an extremely appealing young couple parted by the disaster, eventually became the second of three Countesses among the Lusitania’s survivors.

It was clear from the day Maud Robinson was born, October 25, 1882, that she would be afforded many excellent opportunities in life. Her parents were affluent residents of Long Branch, New Jersey. She was descended from Martin Kalbfleish, a two term Mayor of Brooklyn. Maud believed in being assertive, even penning an article on the problems of sensitive girls and how they may overcome their handicaps: “Pity the sensitive girl… give me the jolly girl who is perfectly natural and who takes on the world as she finds it and the people as she finds them, too, without worrying over the impression she is making.”

It is not clear how and when Maud Robinson met Elbridge “Blish” Thompson, but they married in 1904, the same year he graduated from Yale University. The ceremony took place on March 31st.

Elbridge Thompson was born on October 2, 1882 in Seymour, Indiana. His family owned the prosperous Blish Milling. He attended Andover and Lake Forest, and studied Metallurgy at Yale.

The couple moved to Colorado shortly after their marriage; Blish was interested in developing mining property there. They moved back to Indiana a year later, and he was elected secretary of Blish Milling. The Thompsons were active in politics, and Elbridge was a leader in the Republican County Organization. He and ‘Maudie,’ as he affectionately called her, took part in community affairs such as ‘The Festival.’ He drove his roadster, uniquely decorated as a battleship, while his wife good-naturedly rode by his side.

The Thompsons planned a three month trip, combining business and pleasure, on which they would tour England, Scotland, and Ireland. They booked passage on the Lusitaniaand were assigned cabin, A-21. A few days later they upgraded to a suite with a private bath, B-68, for which they paid $500.

Maud and Blish enjoyed their vacation, spending time with other couples, such as Harry and Mary Keser. They befriended a pair of families with children; the Hodges and the Lucks. It turned out to be a wonderful voyage for them, comparable to a second honeymoon. They made plans to awaken early on May 7th to watch the sun come up:

|

| “Blish” Thompson. Courtesy Charlotte Sellers. |

|

| Maude Thompson Mike Poirier Collection |

About 4:30 or 5:00 A.M., the day of the disaster, husband and myself had dressed and were standing on ‘A’ deck to watch the sun rise. At that time, we saw a battleship off on port side and traveling in the same direction as the Lusitania. The latter was moving very fast at this time. The battleship was close enough so that we could see the whole vessel and its lines distinctly. The fact of the presence of this battleship has not been mentioned, to the writer’s knowledge, by anyone.

We were eating lunch at the time the torpedo struck the ship. Just a few minutes previously I had noted the ship’s clock in order to set my watch, and I remember that it was just 2:05 P.M.

The impact of the torpedo against the ship could be plainly felt; the noise of the impact, however, was not like that of an explosion but made a “jamming noise” like a heavy boat will make in rubbing against a piling, for instance. There was no noise at any time like an explosion, and no further sound following the striking of the torpedo.

My husband and I immediately jumped up from the table, the former exclaiming “we are torpedoed!”

We immediately ran up the stairs leading from the dining saloon. On the stairs was the only time and place that we saw any of the ship’s stewards or officers (except one). They told us to take out time and keep calm.

We went immediately to B deck and helped Mr. and Mrs. Hodges and their two small boys. The entire Hodges family was lost. After arriving at b deck, Mr. Thompson went to his cabin, B-68, to get life belts. He returned with two life belts, also coats and sweaters, which we put on. After a moment he went back again to his cabin for his passports and money.

After rejoining me, we went up on the A deck. On A deck we saw the Keser family of Philadelphia, and also Mrs. Luck and her small sons. Mrs. Luck had no life belt, and Mr. Thompson removed his and together we put it on Mrs. Luck. These were the only people whom we saw at this time and place.

While on the A deck, the single member of the ship’s crew above referred to came past us. He was telling the crowd, “The ship is perfectly safe. You are alright.” at this time and place, also, the writer heard the order given from the bridge “Lower no more boats.”

After we had been on this deck about ten minutes the boat sank, plunging bow foremost with extreme suddenness. The plunge was entirely without preliminary warning. Previous, the ship had listed to starboard to such an extent that it had been difficult to walk up stairs. Impossible to say how far the ship had settled prior to sinking.

When the ship plunged, it stood up almost perpendicular and thereby swept everyone overboard in a mass, and we were swept half the length of the ship. The writer does not remember striking the water. The first sensation came to her under the water. Did not see her husband again after the ship plunged.

The writer was in the water only a short time and was picked up and taken on a small raft, on which there were fifty others, of which only a small number, about fifteen, were passengers. Was pulled about the raft by Guy R. Cockburn, 10 Warrington Crescent, Mada Hill, London W. England.

We were three hours on the raft and were being carried out to sea when the party was picked up by the tramp steamer Kretnia [Katrina- authors] The crew on this boat did everything possible to assist those whom they had rescued. We were taken to Queenstown.

Maud was taken to the Admiralty House with Amy Pearl and Rita Jolivet. Rita claimed to have taken the two women down to the Queens Hotel to care for them and Lady Allan. There was no sign of Elbridge, so she sent home a telegram that read, ‘Maudie safe.’ Unfortunately, it was transcribed incorrectly, and read ‘Maud safe I also.’ The following day, she sent another saying,‘ I am safe waiting news from Blish.’ The family, confused by the contradictory messages, questioned the telegraph operator from Mays, Indiana and learned that a mistake had been made.

Maud continued searching, but could not find any trace of her husband. She sent another telegram asking for advice as to what to do. She finally decided to proceed to London, to the house of her friend Mr. Raikes, to await any further developments and to convalesce.

She was ready to come home by June. There had been no word of her husband for almost a month so there was no sense in remaining overseas any longer. She booked passage on the St. Paul, which was to arrive in New York on June 13, 1915. The St. Paul carried home many Lusitania survivors; James Leary, Charles Sturdy, Herbert Colebrook, Doris and Joseph Charles, Percy Rogers, Ogden Hammond, and Virginia Loney, listed as Virginia Sedgwick. Two Titanic survivors, Robert and Eloise Daniel were also aboard. Maud’s sister and some Thompson relatives met the ship.

Elbridge Thompson’s memorial service was held on June 18th, at the First Presbyterian Church in Seymour. Reverend Lewis Brown, who delivered a short address on “Immortality,” conducted it. People from all walks of life attended the service; from employees of Blish Milling to Blish’s roommates from Yale. Soon after, Maud endowed Yale with a scholarship of $600 annually to the Sheffield Scientific School, which was to be awarded to graduates of Shields High School, Seymour, Indiana.

Blish’s two cars sat in the garage of the Thompson home. Maud decided that she would have the National roadster rebuilt as a scout car. She took the other National, a touring car, to France herself and turned it over to the Red Cross. She decided to stay and work with the humanitarian organization throughout the war. She met Count Jean de Gennes, a French fighter pilot. He was twelve years her junior, but despite their age difference, they fell in love. The two married on November 17, 1917 in Paris. She gave birth to a son, Jean-Marie, on December 20, 1919. When the child was a year old, Maud and the Count took him to visit with Blish Thompson’s relatives. Maud still had an active interest in the Blish Company, and she occasionally returned for board meetings, but she considered France her home.

Maud’s marriage was a happy one but, once again, tragedy struck. Her husband, a pilot for Compagnie Aeropostale, was killed in a plane crash in 1929. She was left with a nine-year-old son to raise. She may have considered moving back to the United States to be near her family, but she ultimately chose to stay in France.

Maud remained in Paris through World War 2. Her son, Jean, joined the Free French, crossing the Pyrenées in November 1943, and was soon fighting for RAF, aboard a Halifax on bombing raids over Germany

The Countess de Gennes returned to the United States aboard the French ship, Desirade, in early 1946, and settled in New York. Her son was working for Air France by that time. She spent the remainder of her days in Sunnyside, Queens, passing away on May 17, 1951. Her final wish was to be buried in France, and so she was buried in Paris, beside her husband, in the Montparnasse Cemetary.

Charlotte Luck, to whom Blish Thompson surrendered his lifebelt, did not survive, nor did her sons Elbridge, 12, and Kenneth, 8. Charlotte and her children had stayed in San Francisco with her mother, Mrs. Field, during Arthur Courtland Luck’s extended business trips abroad, although their home was in Worcester, Massachusetts. None of the bodies were recovered, and Mr. Luck was eventually awarded $20,000.00 for the loss of his family. Frances Lapham Field, Charlotte’s mother, was awarded $5000.00 for the loss of her daughter’s financial support.

Rita Jolivet

Rita Jolivet, stage and screen actress, remains one of the most frequently referenced of the Lusitania passengers. Unlike many others survivors, she apparently assimilated the memory the disaster quite well. She spoke frequently of the sinking, but she did not seem haunted by it, and the nightmares, panic attacks, guilt and anger which plagued the later years of so many of the Lusitania’s survivors do not seem to have been a major factor in her life. Her fame as a survivor has outlasted the acclaim of her dramatic career.

Rita Jolivet, stage and screen actress, remains one of the most frequently referenced of the Lusitania passengers. Unlike many others survivors, she apparently assimilated the memory the disaster quite well. She spoke frequently of the sinking, but she did not seem haunted by it, and the nightmares, panic attacks, guilt and anger which plagued the later years of so many of the Lusitania’s survivors do not seem to have been a major factor in her life. Her fame as a survivor has outlasted the acclaim of her dramatic career.

Rita Jolivet had her first success on the London stage, but was best known in 1915 for her long run Broadway in the hit, Kismet ,and her critical success in A Thousand Years Ago. Her first major motion picture, The Unafraid, by Cecil B. de Mille, had just opened when Rita boarded the Lusitania that May. The film has survived, and shows that Miss Jolivet’s vibrancy onstage made the jump to the big screen. She seems perfectly at home before the camera, and her acting style is subtler than is often found in films of that era.

Miss Jolivet, according to her family and contemporary reviews, was a born raconteur. Vivacious, expressive, and quite flamboyant, the Lusitania disaster lectures she gave in conjunction with her Lusitania movie, Lest We Forget, were given high marks as both entertainment and education. Rita’s 1918 testimony at the United States Limitation of Liability hearing remains the best, and least fanciful account of her experiences on May 7, 1915. It is presented here in its original Q&A form:

Q. When did you make up your mind to sail; when did you go on the ship?

A. At 8 o'clock in the morning I made up my mind to sail, and I arrived at the dock at five minutes to ten. She was due to sail at 10 o'clock. The reason for my doing so was because the Lusitania was supposed to go quickly, and I wanted to see my brother before he left for the front.

Q. Had you expected, or thought of going on the St. Paul that same day?

A. Miss Ellen Terry had suggested my going, and I said no, that I was in a hurry and was on schedule time and was afraid of not seeing my brother.

Q. When did the steamer finally sail, as far as you recollect?

A. She finally sailed about 1 o'clock.

|

| Rita circa 1910. |

|

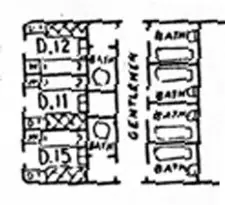

| Jolivet Cabin (D-15) (Courtesy of Paul Latimer) |

Q. Your stateroom was on what deck?

A. On Deck D; it was a very bad room, because it was the last moment, and I had to take an inside cabin.

Q. Were you alone?

A. Yes, but to my great surprise I found my brother in law was going back too. I met him on the boat. He had also decided to hurry back to his wife, and she was in England.

Q. There was no special circumstance on the voyage up to the day of the torpedoing?

A. Not at all, except for rumors.