William Meriheina : An inventive survivor

The story of William Meriheina, Lusitania survivor and inventor of the car radio.

RMS LUSITANIA: SPEED & STEALTH by David E Olivera

One occasionally runs across a story that expands beyond its obvious borders, and continues to expand each time it seems like the last new plot twist has been uncovered. This account began, innocuously enough, with a friend of ours telling us that the Finnish word for “seaweed” is meriheinä. This caused us to discuss, again, a certain Lusitania survivor who seemed to vanish after a 1917 arrival-by-ship in Philadelphia. That very night, a happy discovery in a Library of Congress publication allowed us to begin untangling the story. Two years later, surprising facts about Lusitania survivor William Uno Meriheina, the man who jotted down impressions of the disaster while atop an overturned lifeboat, continue to surface. It would not be stretching a point to say that Meriheina influences the lives of billions of people to this very day. It would not be stretching a point to say that Meriheina participated in the birth of one of America’s iconic sporting events. And, with the Lusitania his third transportation disaster, it would not be stretching a point to say that he was a very lucky man indeed.

He was born in Helsingfors, Russia, now Helsinki, Finland, on July 11, 1888, the son of Karl and Charlotta Malvenius Merihena. His father immigrated to the United States, via New York, aboard the Stuttgart, in December 1892. The rest of the family immigrated at some point in 1893. No record can be found of when, or to where, Charlotta, David, William, and Hilda Meriheina crossed, but later censuses consistently give the 1893 date. They settled in Fitchburg, Massachusetts, where Karl worked as a fresco painter. Mr. Meriheina then spent several years running a confectioner’s shop on Laurel Street in Worcester. Two daughters, Alice and Merriam, were born in Worcester. However, by 1900, Mr. and Mrs. Meriheina and their five children were living at 2492 Eighth Avenue in New York City. They had shortened their last name to Heina and, except for when traveling, William Uno Meriheina would go by the name William Merry Heina for the rest of his life.

He was born in Helsingfors, Russia, now Helsinki, Finland, on July 11, 1888, the son of Karl and Charlotta Malvenius Merihena. His father immigrated to the United States, via New York, aboard the Stuttgart, in December 1892. The rest of the family immigrated at some point in 1893. No record can be found of when, or to where, Charlotta, David, William, and Hilda Meriheina crossed, but later censuses consistently give the 1893 date. They settled in Fitchburg, Massachusetts, where Karl worked as a fresco painter. Mr. Meriheina then spent several years running a confectioner’s shop on Laurel Street in Worcester. Two daughters, Alice and Merriam, were born in Worcester. However, by 1900, Mr. and Mrs. Meriheina and their five children were living at 2492 Eighth Avenue in New York City. They had shortened their last name to Heina and, except for when traveling, William Uno Meriheina would go by the name William Merry Heina for the rest of his life.

The 1940 census tells us that William Heina completed two years of high school. The New York City death index establishes that his father died in 1901, at age 38. Charlotta Heina never remarried, and so her children presumably had to leave school in order to support the family. All that is known about William from these years is that he worked as a NYC taxi driver.

Heina’s life comes into sharper focus in 1909, when he began making a name for himself in auto races at Brighton Beach. He was discovered by the Lozier car company, and participated in the inaugural events of what would become the Indianapolis 500, as part of their team. The Indianapolis Motor Speedway had opened earlier in the year, and was holding its first major event; a 100 lap, 250 mile, race around the half-completed course. Lozier cars were expensive in 1909, costing the equivalent of $187,000 in 2013 funds, and so this represented a great publicity coup for Mr. Heina.

Heina in a Lozier

C.A. Emlse, retail sales manager of the Lozier Motor Company, who is at the present time at the Indianapolis Motor Parkway course managing the Lozier race team, sends the following extract from the Indianapolis News of Tuesday, Aug. 17:

“Mr Heina, at the wheel of a Lozier, attracted considerable attention. Heina first gained publicity in the last twenty-four-hour race at Brighton Beach, where he made a splendid showing. His fastest trial yesterday for the full two miles and a half of the outer course was made in 2 min. 16 sec., which proved to be the fastest time of the day. Heina takes the place of the former Lozier Driver, Ralph Mulford, who will retire from the racing game in the near future.”

Motorists to Burn Space in Indiana

Aug. 18 - Hundreds of automobilists from all over the United States are here to attend the races at the Speedway, and which will begin tomorrow. Automobile clubs are arriving from Chicago, St. Louis, Louisville, Columbus, Cleveland, and Detroit. The trains brought officials and visitors from New York and other distant cities.

Fred J. Wagner arrived last night, inspected the course, and mapped out his plan for starting the cars. A.R. Pardington, of Long Island, one of the judges, is expected late today.

William Heina, on a Lozier, made the 2½ mile circuit at the Speedway in 2:16. The trial record for that distance on this course is held by Zeingal, in a Chadwick, and is 2:02.

Ralph De Palma, in his Fiat, and Barney Oldfield, in his Benz, were on the speedway today, “limbering up” their machines. They fairly “burnt up” space, hitting only the high places around the course.

The Horseless Age, founded in 1895, was the first car buff magazine. It covered the Indianapolis race, and allows us to see how Heina placed in a few races, in competition with industry legends like Chevrolet, Stutz, and Oldfield.

The Inaugural Races on the Indianapolis Speedway

Several new track records, from 1 to 200 miles, were made at the three days’ meet held on the Indianapolis Motor Speedway near Indianapolis, August 19-20-21. William A. Bourque, driver, and Harry Holcomb, his mechanic, both of Springfield, Mass., who had one of the Knox entries, were killed on the opening day of the meet, and three spectators were killed on the closing day.

The deaths of Bourque and Holcomb occurred during the 250 mile race on Thursday, for the Prest-O-Lite trophy. The cause of the accident could not be determined, but witnesses said both men looked back and the car ran into an open ditch along the home stretch, turning over. Holcomb was thrown against a post and killed instantly. Bourque died within fifteen minutes.

There were rumors after the first accident that the 2½ mile course, upon which the events were run, was not in fit condition for the speed tests that were undertaken. On Friday morning, members of the A.A.A. made a trip around the track, ordered a few changes, and the ditch covered, and gave sanction to the races.

There were rumors that the 300 mile race would be cut shorter, or that drivers would be changed, but it was decided to carry it out according to the program. In his 190th mile, Charlie Merz, a 21 year old boy driving a National, crashed into the fence, instantly killing William Kellogg, Benjamin Logan, and H.H. Jolleffe, all of Indianapolis. Merz miraculously escaped with a few scratches, while his mechanichian was probably fatally injured.

Directly after this accident, Bruce Keene, driving a Marmon, crashed into the overhead bridge over the track. Keene and his mechanician were slightly hurt. It was seen the drivers were in no condition to continue, and in the ninety-fourth lap the A.A.A. officials called the race off. The leading car at that time was a Jackson, driven by Lynch, with De Palma in his Fiat second, and Stillman, driving a Marmon, third.

Only half of the five mile course has been completed. While the track in front of the grandstand and for some distance each way was oiled, the remainder of the track was covered with fine stone particles, which frequently broke the drivers’ goggles and gave them intense pain. Chevrolet, driving a Buick, was obliged to get out of the 250 mile race because he was almost blinded.

The crowds at the races were all that could have been expected, about 12,000 attending the opening day, 22,000 on Friday, and about 30,000 Saturday. From a financial standpoint, the meet was a success. It is understood that another met will be held next month, or in October.

* * * * *

Event No. 4. Ten miles for the cars to compete for the Wheeler & Schebler trophy, under 600 cu. Inches piston displacement; Aitken, driving a National, first; time 9:26:6. Lytle, driving Apperson, second, and Heina, driving a Lozier, third.

Event 6. Ten mile, free for all handicap Ford trophy.

-

Place 1. Car 8. Len Zengel. Chadwick

-

Place 2. Car (?) Johnny Aitken. National

-

Place 3. Car 66. (?) Ford. Stearns

-

Place 4. Car 5. William Heina. Lozier

-

Place 5. Car 27. Barney Oldfield. Benz

-

Place 6. Car 24. Ralph De Palma. Fiat.

Heina returned to New York City in time to compete in the next series of races at Brighton Beach. His success there during the early summer of 1909 was not commented on in the city papers, but the series of accidents that ended the August race drew national coverage.

Fully 15,000 persons were present when the fatal smash occurred last night which crushed the life out of the mechanician, Leonard Cole, who was in the Stearns car with Laurent Grosse, and more than half that number remained until daylight. During the night there were many spills which forced several cars to take trips to the camps for repairs. The Rainier and Renault racers were more lucky than the others, and they raced each other nip and tuck for five hours amid the cheers of spectators until they got on level terms shortly after six o’clock. Two hours later they were still tied for first place.

One of the early morning accidents was the turning over of the Lozier car, under which driver Heina was buried, but he was not even scratched. He had a rest of nearly two hours before the car was put into commission again.

Heina resumed racing later that morning, only to meet with a second, worse, accident.

The Lozier car, which was out of the race for three hours during the night was in trouble again this morning. At 8:25 o’clock it jumped from the track into the outfield at the turn into the back stretch. This was Heina’s second escape during the race, as he was found unhurt under the Lozier when it turned turtle after midnight last night.

The cause of the second accident to the Lozier was the bursting of a tire. The car turned over twice, and although the racing machine was wrecked, neither of the occupants was scratched. At the Lozier camp it was thought that the car could not be repaired today.

A casualties list was printed in the papers the following day, which showed Heina seriously injured. Perhaps a third wreck took place after the papers went to press on race day:

The Dead:

Leonard Cole, mechanic of the Stearns car, killed instantly.

The Injured:

Laurent Grosse, driver Stearns car. Will die.

Cyrus Patschke, driver Acme car.

Hugh Hughes, driver Allan-Kingston Car, badly burned, in hospital.

William Heina, driver Lozier car, leg severely hurt.

William Giblin, mechanic Lozier car, severely injured.

Patrick Corrigan, Pinkerton man. Leg and knee broken.

Mechanician, Acme car, name unknown. Unconscious in hospital.

Heina would remain part of the auto industry for at least 21 more years, and would do extremely well for himself in that capacity. He patented items as diverse as axles and tire patches. No record of him racing after 1909 can be found; his true skill was as an inventor.

William Heina married Esther Griffin, of New York City, around 1908. They lived with her parents on the Upper West Side, and had a daughter named Charlotte. William continued to supplement his auto industry earnings by driving a taxi. He joined the flying craze, and began appearing in the Aviation News sections of the NYC papers. He was present, as a flyer, when a legendary figure in New York society took his first plane ride:

On the Aviation Field

Lieut. Col. Cornelius Vanderbilt took his first ride in an aeroplane at the Hempstead Plain Aviation Field quite unexpectedly on Saturday. The Colonel visited the field with Major General John F. O’ Ryan, Commanding National Guard of New York.

Col. Vanderbilt had no intention of taking an aerial ride, and had even promised Mrs. Vanderbilt that he would not attempt it, but the thrill of the aerial atmosphere of the aviation field, coupled with Aviator Beatty’s assurance of safety, determined him upon trying a flight, and he came down after circling the field three times at a height of 500 feet, saying he never enjoyed eight short minutes so much in his life….. McLaughlin’s Red Devel, with William Heina aviator….

Shortly thereafter, Esther Heina made her first appearance in the press, as part of the circle of brave young NYC aviators:

Took Mother in Airship

Hempstead, Long Island, July 30- More aeroplanes were in the air at one time here tonight than at any time since the international aviation meeting. Cecil Peoli, the 18 year old aviation prodigy, took his mother more than 3,000 feet in the air, climbing to this altitude in a trifle more than nine minutes. Peoli also took as a passenger Mrs. William Heina…..

Heina’s next newspaper appearance was far less romantic.

Monoplane Falls on Another in Midair

Garden City L.I., Thursday- Two aeroplanes, one a Bleriot monoplane driven by James Steinhauer, and the other a Walden monoplane piloted by William Heina, formerly an automobile racer, were in collision in midair at the old Garden City aviation field this evening.

A full account of the accident:

Aeroplanes, flown by James Steinhauer and William Heina, collided Thursday evening while in action over the field in Garden City, and crashed to the ground. The men saved themselves by clinging to the machines, and the spectators who disentangled the double wreck found them both well-buried, but unhurt except for minor cuts and bruises.

Neither of the flyers was expert. They had chosen the evening hour as likely to give them a free course. Steinhauer lifted his Bleriot into the air first. When he seemed safely aloft, Heina followed and was soon flying directly under Steinhauer.

Suddenly, Steinhauer lost control of his gearing. The machine dropped plumb on top of Heina’s, drove it down, and pancaked it on the ground. In the fall, Steinhauer’s machine turned so that it landed on a wing and went over bottom up.

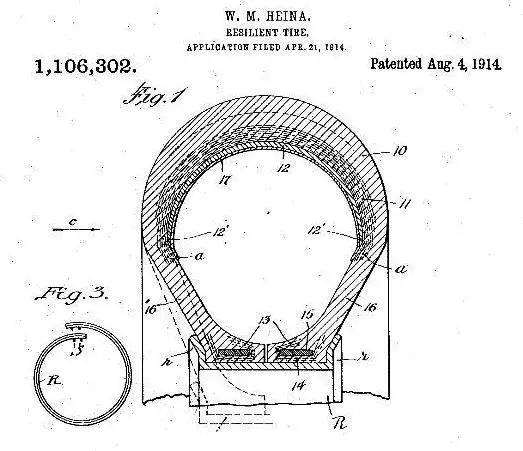

A year or so later, William Heina was working for General Motors, in the New York City Buick division. He patented an improved automobile tire of his own design in August 1914, and the following March he and two partners, Ernest Derks and Edward Kammler, founded the Heina Tire Company, manufacturers of tires and rims, with $15,000 capital stock.

1914 Tire patent

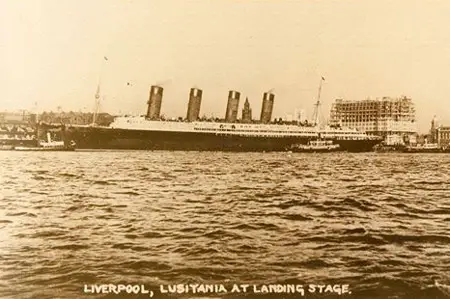

Heina would be an absentee owner. According to one account he had accepted the job of overseeing the new General Motors Johannesburg facility. Another account states that he was based in Johannesburg, but would travel Africa demonstrating General Motors self-starting ignition systems. He began his journey to South Africa aboard the Lusitania, on May 1, 1915. He traveled under his birth surname, Meriheina.

SAGAPONACK

BW NEW YORK NY

To MERIHEINA "LUSITANIA" WSK.

GOODBYE BEST WISHES SUCCESSFUL VOYAGE

GENERAL MOTORS.

Esther Heina met with the press two weeks after the disaster, at the family apartment on West 134th Street in Manhattan. She had received a letter from her husband, written aboard the ship, plus two Lusitania postcards he filled out with impressions while atop an overturned lifeboat. Esther’s words, perhaps polished a bit by the press:

My husband is only twenty-five years old, but he is already an electrical expert of genius, a wonderful automobile racer, and an unusually good swimmer. A braver man never lived. He is a Russian Finn, well educated, and devoted to America and its institutions. He was on his way to South Africa as a special agent of the General Motors Export Company. In spite of his long exposure in the water and his exhausting efforts in saving women and children, he cabled that he would continue his trip to South Africa.

William Heina seems to have had a pocket date-book with a locking cover. The diary-letter he composed for his wife during the crossing survived immersion, folded inside the book, and so too did the postcards he filled out while awaiting rescue:

The Lusitania. Saturday. On the way out of New York Harbor, and everything O.K. At Ambrose Lightship we pass the British man of war Bristol: then we sight the British converted cruiser Caronia. We stop, and a boat load of ‘Tommy Atkins’ comes on board, presumably for mail and exchange of messages. No wireless is used. Received wireless from General Motors Company. When I said that no wireless is used, I meant that we receive messages but cant send any. Later in the afternoon, we passed the American Line steamship New York, also bound for Liverpool. Then we sighted a French battle cruiser of the super-dreadnought type, and this cruiser turned and followed us, but gradually was left behind. We are making about twenty five miles per hour.

Had a grand time at lunch and dinner. What delayed our start was the fact that the Anchor Line sent up about 300 passengers that were booked to go on board one of their ships, and at the last minute the ship was called out of passenger service, presumably for transport purposes. Feel fine, and am going to sleep well.

Sunday- Woke up, had a dandy salt water bath. Enjoyed a grand breakfast. Sunday services were held on board. Foggy day, and quite rough ocean. At noon Sunday our log recorded 453 miles, or halfway to Newfoundland Grand Banks. Day passed with concerts in the drawing room. Plenty of seasickness on board, but I feel splendid. Lunch and supper fine. Because of rough weather nearly everyone turned in quite early. At midnight, I understand we passed a British cruiser. I noticed a great deal of light signaling going on. Evidently we are being carefully convoyed all the way across. Still, no ships are in sight for any length of time. We have passed quite a few vessels bound both ways. Owing to our great speed, we don’t stay in sight of any one ship very long.

Monday- Feeling great. Fog is prevalent. Dandy meals- passed a bunch of ships. We had a concert, games, races, and drive whist, and various other entertainments. Am enclosing today ocean newspaper. Rolling quite a little, but am not affected in the slightest. Have an M.D.- surgeon- as a room mate. We have become quite good friends. He is going to offer his services to the Allies as a surgeon. He is Dr. D.V. Moore. He is well educated and provides a good, companionable, room mate. Am acquiring an extensive knowledge of Scotch, English, and Irish dialects and you must not be surprised if I talk funny when I come back to you. Several of the passengers are grand singers, and they keep everyone interested. I am studying my work, and I think my trip will do me good.

Tuesday- resumption of games on deck today. Dandy sunshine weather- feel fine.

The two drawing room postcards Heina filled out while awaiting rescue read:

Card #1: Ship sunk. Seventy of us on a raft. Believe the lost will amount to half of our passengers. May we all be happy in our destiny.

Card #2: Steamship coming: also sail boats. Hope most of us will be saved. Tis a conquest of kings. May they be glorified with a crown of life and death. Hope the lives of the lost ones will pay the score.

The Lusitania account Heina mailed to his wife was also sent to General Motors as his report:

The terrible crash finally came. First, I will say that outside of a few bruises and pains and exhaustion, chills and fever, etc, I am feeling fine. Am stopping at this hotel and will probably remain here for a few days till I feel right again.

We were eating lunch at the time, when suddenly, with absolutely no warning, we felt a heavy explosion up forward, near the first cabin section, a grinding and a ripping. The boat immediately lurched to the side you were looking at as we were tied to the New York dock. She settled so much that dishes fell off the tables and it was difficult to walk the aisle between tables. There was very little panic- individuals moaned and cried and just the suggestion of a rush for the exits. Those that left the second cabin dining room probably were the ones that were saved, mostly.

About five seconds after the first crash, a second one came along, with the same sinking sensation on the one side. The men did a great deal for the women and children, but remember the boat sank to the bottom in less than twenty minutes, and after the first ten minutes the boat had rolled over so that the side was more level than the decks. The lifeboats that were lowered were either overturned or smashed against the side of the boat, dumping the human loads into the ocean. I don’t pretend to describe the total scene, it was too horrible, but I did everything I could to help the women off. I placed a life belt on myself, and placed several elderly women in life rafts that might tear loose from the decks when the boat sank, which they finally did. The people who reached the decks were the only ones saved, as the ship sank in a flash when she finally started nose downward. On sinking, her boilers blew up and her deck roofs blew off. I had faith in the boat not sinking and therefore remained on the back bridge till I was washed off.

The internal pressures created in the hull by the inrush of water was sufficient to blow out port hole plates, and the air shot out of these like steam. I saw many bodies floating away deep in the water.

The sight of people falling overboard and sinking, with apparently no effort to swim, was maddening. Well, when the final plunge came, I believe that I was the last, or one of the very last, to get off. I tried to jump, but got fouled with the angle of the deck and the rail posts, and was washed off only to be slammed back downward with the hull. I lost consciousness and then came to with the bright sun shining in my eyes. It was cold and I felt stunned, but I struck out for an overturned lifeboat that was about a city block away. There were people all around, both live and drowned. On reaching the boat, I hung on to the side of the rope for a minute or so, when a man grabbed my neck, placed his arm over my shoulders, and pulled me off. I turned and hit him. He weighed over 200 pounds and I could not shake him off, so I sank purposefully and he let go at once. I again reached the boat and the man also had a finger grip on the rope. Several others were hanging on. One after another we managed to climb up on the slippery sides and lie on its keel. I finally reached out and helped this particular man up on the boat and also several others. We finally had about twenty men and women on the overturned lifeboat and she threatened to sink, when another overturned boat came near and some of the men made for it. We kept those two overturned boats together, loaded with humans half dead, and some dead.

Then a broken raft was forced near us, and we placed all the women and children thereon. Right near us was an upright lifeboat, but entirely submerged so that only the oarlocks were visible at times. This boat contained about a half dozen women and twenty men. We finally got the women off her on the raft, and the men remained, several drowning therein. We had a lot of trouble with our crew of these two overturned lifeboats- the crew, I mean, were the people thereon. Some wanted to paddle to shore, which looked twenty miles off, and others wanted to save their strength. We sang “Tipperary” a couple of times (sacrilege) and then due to the women’s crying, and begging us to stop, we sang “Lead, Kindly Light.” men were bleeding and injured.

Then after more than three and one half hours, the fleet from Queenstown came into view. They picked up most of the other boats first, as we were farthest away, and then finally came to us. All this time we were constantly adding to our crew and settling deeper and deeper. In the three and one half hours’ agony I found time to take out my fountain pen, which I still had, and dug out a couple of wet post cards that I obtained previously from the drawing room of the boat. I wrote my impressions very mildly on two of them. The rest of my time was taken up either pumping arms up and down, or squeezing some poor “half-gone’s” wet clothing. We finally had more than 70 on our improvised raft. Then they picked us up. The Indian Empire was our rescue boat.

William Meriheina returned to the U.S. in March 1916, crossing to Baltimore from Cape Town, South Africa, aboard the Chepstow Castle. He listed Esther as his closest U.S. contact. He crossed again in June 1917, arriving in Philadelphia aboard the City of Athens. He gave General Motors Co, p.o.b. 1008, Johannesburg, as his African address, and the Hotel Astor, NYC, as his American destination.

There is no evidence that William Heina ever returned to South Africa. The vessel upon which he arrived, the City of Athens, departed for Cape Town in July, and struck a mine on August 10th while in sight of the South African coast. 19 were lost. Perhaps this reminder of the dangers of a wartime crossing influenced him to remain in New York. Or, perhaps, something better awaited him in the United States.

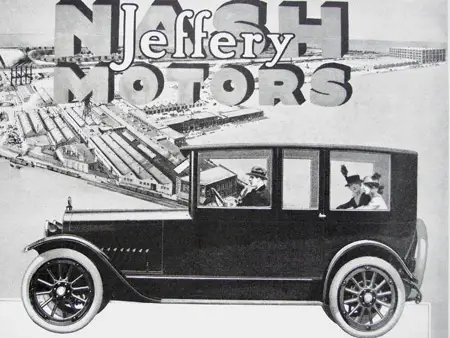

C.T. Jeffrey, Lusitania survivor, had inherited the popular Rambler Motor Car Company from his father. He reconfigured the Rambler into the newer, more luxurious, Jeffrey, which did not enjoy the success of its predecessor. Jeffrey Motors, however, manufactured a durable four wheel drive truck that proved to be a solid hit. Former General Motors president Charles Nash bought out C.T. Jeffrey in 1916, and renamed the Jeffrey automobile and truck Nash. 1917 was the first year for Nash Motors, and William Heina was soon crossing the U.S. promoting the new, improved, line. We cannot establish, yet, if Mr. Nash contacted Heina in South Africa and made him an offer too good to refuse. He was on the road promoting Nash Motors very soon after stepping off the ship, and so it is possible that such was the case.

Heina arrived in San Antonio, Texas to promote Nash cars, in the fall of 1917. The local newspaper, however, was more interested in his Lusitania experiences:

SURVIVOR HERE OF LUSITANIA’S FATAL VOYAGE

W.U. Meriheina of Nash Motors Co. Recalls His Harrowing Experience.

FOUR HOURS IN THE WATER.

In this time of rapidly moving events, the sinking of the Lusitania may seem merely one event in a long line of horrors that have come out of this war. But to a man who for four hours struggled in the cold waters of the ocean, clinging on to bits of driftwood, to overturned lifeboats, to rafts, or trusting to a life belt, the memory is one that is deep burned into his soul.

William U. Meriheina, special representative of the Nash Motors Company, who is now in San Antonio on business connected with the Nash cars and trucks, is such a man. Though he speaks of his terrible experience quietly, with no attempt to do more than make clear statements of events, h does it with a certain definite effort, and all of his rigid self-control cannot prevent the tears from appearing in his eyes.

“I sailed on the Lusitania” he explained, “because I thought of all the vessels it would be the safest. We were to go aboard at 10 o’clock in the morning, and so in the bustle of telling my wife and daughter goodbye, and getting aboard, I did not look at the papers. It was, therefore, not until we were something like 50 miles out from New York that I opened a morning paper which I had purchased as I came aboard and saw the advertisement which warned the passengers not to sail.”

He spoke of the quiet and pleasant trip across the Atlantic, and how any fears the passengers might have entertained were quieted by the meeting with several warships of the allies, British and French. He also told how the speed of the vessel was slowed down upon approaching the coast of Ireland, and how the captain explained that they were waiting for high tide to cross a certain bar that lay between them and Liverpool.

“I was in the dining room at the table when the first crash came” he continued, “and it sounded as if the vessel had struck a large jagged rock and was simply ripped open. Everyone knew at once what had happened, and pandemonium reigned. Everyone was shrieking and running back and forth as if they were possessed, and the ship’s crew tried vainly to quiet them.

“Conditions were not improved when the second torpedo struck the boat. It immediately listed far to one side. I started below to my cabin to get my life belt, but I never did get down, for the water was starting to come into the ship. I snatched four life belts from a cabin, went on deck, gave the belts away, and went down for some more. I fastened one belt around me and went again on deck. The crew was still quieting the crowd, assuring them that the boat would not sink and making every effort to get the people into the lifeboats.”

He told how, from the stern of the Lusitanian, which was some 75 feet above the water ordinarily, he watched the great vessel gradually list more and more until walking on deck was practically impossible. The bow then took a dip forward and the vessel began to sink.

“It went down at the rate of twenty miles per hour, and I hung on to the rail and watched the people, screaming and shrieking, being washed from the deck into the sea. Finally the vessel had settled so that I concluded I’d better jump. I climbed on to the rail, and was lurched off, thrown skidding across the deck, wrenching my side and hand, and I do not remember anything else until I found myself in the sea. The Lusitania had gone down.

“This was the most terrible part, this long wait, clinging to anything, believing that every moment would bring death, making the last effort with failing strength to hold on just a little time longer.

“Many things, hundreds of incidents, happened while we waited there those four hours in the water; things I hate to talk about, things it would take a long time to tell”

But part of the time he floated, borne up by his life belt; again, he hung to an overturned lifeboat, until too exhausted to hold on any longer, and finally he found a place on top of a lifeboat, where he stayed until he and all those still alive on the boat were picked up by a minesweeper.

Though Mr. Meriheina is very modest and has little to say about the part he played during those hours in the water, his time was spent in not merely trying to save himself, but in trying to drag women and children out of the water and push them onto the overturned boat in safety. That a great many were saved by him in this way, the various tokens of respect, such as watches, medals, pins, etc, given to him by grateful friends and relatives speak eloquently of his heroic work.

He continued the part of good Samaritan after he, with the other survivors, were taken to Queenstown, Ireland. Though he had to go around the streets of Queenstown in a blanket fastened about the waist with a necktie, until he received money from London for clothing, he put in his time searching in the morgues for unidentified bodies, trying to reunite separated members of families, trying to fit out women and girls with clothes.

“They were in misery and distress” he said, “and I was in misery and distress. It was nothing, and it made me feel better to try to help.

“The morgues were horrible, though” he continued, “ and the worst of all experiences was my hunt for the bodies of a man and his wife with whom I had become acquainted o board. I knew that their family lived in London, and I telegraphed. Then, when I had found the bodies I tried to make them presentable, but as I could get no one to help me, it was terrible work.”

He told how the babies, some 20 of them, had died with happy smiles on their faces, but how the faces of all the grown people were simply frozen with horror.

“Many a time, months after the accident” he concluded, “I would wake up in the middle of the night with the whole ghastly thing before us, the sinking of the ship, the hours in the water, and then the pitiable state of the survivors and the horror of the dead.”

Not long after this dreadful experience, Mr. Meriheina sailed for South Africa and since that time has gone completely around the world.

Heina’s two accounts show that he was an excellent witness. His story remained consistent between 1915 and 1917, with one interesting exception. His 1915 account described the lack of panic in the dining room, with isolated outcries and a hint of pushing for the door. His 1917 account describes pandemonium. Most very early accounts describe the same behavior; calm but hurried, with a few people losing their heads. Much vitriol was hurled at the crew. Within a few months of the disaster, survivors began altering their accounts to conform to what was believed to be the norm in such events. Women screamed. Children cried. Foreigners stampeded. Anglo/American male passengers and crew behaved manfully.

He petitioned for American Naturalization on October 17th, 1917, in New York City under the name of William Merry Heina. The surname Merihena was not used again in any context. His association with Nash Motors disappears from the record in 1918. He patented a few automotive devices during this period and became involved in a patent suit involving his 1914 tire design, which was resolved in his favor in 1920, with no mention being made of either Nash or G.M.

The 1920s saw the birth of commercial broadcast radio, and the continuing proliferation of affordable automobiles. The concept of putting a radio into a car seemed obvious enough, but the execution proved difficult. There were radios sold for auto use almost from the first day of commercial broadcasting, but they did not work when the car was running. The cars’ electric starters produced static that would wash out whatever signal the radio was receiving. Car radios, such as they were, could be used at picnics, or outdoor sporting events, or for background noise while doing yard work, but did not function while the car was in motion. These radios were cumbersome separate units, not integrated with the dashboard. They were difficult to install and hard to service. So these expensive gadgets ($150) were never particularly popular.

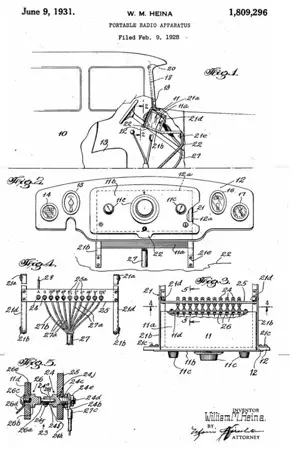

Car radio patent

William Heina set out to produce a radio receiver that would function without interference while a car was running. He named his new business Heinaphone, and set up shop on Queens Boulevard in NYC. 109 cars would be fitted with Heinaphone prototypes, as the invention was refined.

He and Esther divorced at some point between 1920 and 1925. The 1925 N.Y. state census shows her living with their daughter, on Audubon Avenue, and lists her as head of the household. She was working as a telephone operator.

Heinaphone patented their first interference-free car radio in 1926. A second, portable, Heinaphone radio, which could be easily removed from the dashboard for service and repairs was patented in 1927. Heinaphone merged with American Radio Corporation in 1927, and set forth to perfect Transitone- the first radio that could receive broadcasts while the car was in motion. C. Russell Feldmann was the president of the new company, and William Heina vice-president.

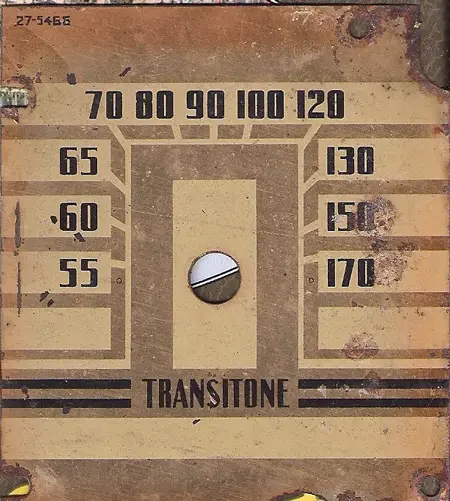

Transitone radio dial

Auto Radio Company Leases Space in Long Island City

Roman-Callman Company has leased for the Sarkisian Realty Company for a long term of years the service and showroom buildings on the north side of Queens Boulevard from Hulst to Van Pelt Streets, Long Island City, to the Traveltone Company.

Tourists to Have Radios for Cars

Summer tourists who have been listening for the call of the open road will not have to say goodbye to their radios this season. These two aids to recreation, providing for touring and for entertainment, have been united in an ingenious device.

The automobile-radio, the invention of William Heina, incorporates a full-sized radio as an integral part of the automobile. Through an interference-dampening device the squawks and squeals which ordinarily would result from the high tension ignition system have been completely eliminated. The radio will function clearly in an automobile speeding through the country at 60 miles per hour.

Heina worked for four years in his laboratory in Long Island City, and with radio sets installed on a hundred different cars, before announcing his perfected invention.

The invention, which Heina calls “Transitone” consists of a six-tube, six volt, radio receiver completely enclosed in a stout copper box and installed behind the automobile dash, with the radio dials placed in the center of the instrument board.

~June 1929 press release.

NEW INVENTION BRINGS AIR PROGRAMS TO PASSING MOTORISTS

New York- May 3.

A new industry, combining the automobile and the radio, bringing all the entertainment on the air to the motorist, made its formal bow at the Automobile Radio Corporation here tonight. The new invention, marketed under the name of Traveltone, was demonstrated to 400 leaders of the automobile and radio world.

Mayor James J. Walker acted as master of ceremonies. Paul Whiteman and his orchestra played a “Wedding March” and then nine leading makes of automobile were unveiled with radios in each, receiving the same program. Among the speakers were Captain E.V. Rickenbacker…

A million dollar concern, the Automobile Radio Corporation, combining powerful interests of the automotive and radio world, has been formed for the manufacture of the invention. Stock is not for sale. The officers are: President C. Russell Feldmann: vice president William Heina….. The company has a manufacturing plant at Long Island City, and an installation plant in Detroit, Michigan.

The cars equipped with Traveltone shown were Stutz, Packard, Graham-Paige, Cadillac, Chrysler, Oakland, Hupmobile, REO, and Pierce-Arrow.

The very first 1930 car to hit the market with a Transitone radio, by Traveltone, was the most expensive Dodge model. The devise was an unqualified success. Automobile Radio Corporation quickly sold their interests to Philco, a company that had the assets and networking needed to successfully market a new product during a worsening global depression. We cannot determine if Heina surrendered all of his rights to his invention, and his patent, with the buy-out, or if he continued to collect some form of royalty.

William Heina still had 46 years left in which to patent new inventions. He remarried, to a woman named Catherine, at some point between 1930 and 1935. They lived in Rochester, Nevada, in 1935 and relocated to Santa Monica, California, by 1940. William worked as an airplane inspector. Santa Monica city directories show that he held that position from before 1940 through at least 1954. The Library of Congress has copyrights on file for articles written by Mr. Heina as late as March 1963, when “What Makes the Apple Fall to Earth?” was published in an unnamed magazine.

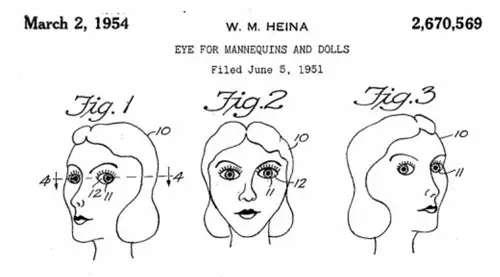

Heina’s rotating eye patent for mannequins dated 1951

The Heinas retired to the west coast of Florida. Catherine died there in 1968, and was buried in Gulf Pines Memorial Park, in Englewood, FL. William died in Valrico, FL, at age 88, on December 12, 1976, and was buried beside Catherine.

The grave of William Heina and Catherine Heina at Gulf Pines Memorial Park, in Englewood, Florida

Photo courtesy of Fred Saar

<p><strong>Profuse thanks are extended to Peter Engberg-Klarström, whose genealogical diggings turned up a huge amount of material and inspired me to finish this piece. Jim Kalafus.</strong></p><p><em>Painting: RMS LUSITANIA- SPEED & STEALTH, Oil on canvas, 24″x18″/60.96×45.72 cm, 2014, Copyright David E Olivera</em></p>